Volunteering for Wellbeing Final Report 2013 – 2016 Social Return

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Museums & Art Galleries Survival Strategies

museums & art galleries survival strategies A guide for reducing operating costs and improving sustainability museums & art galleries Survival Strategies sur vival Contents strategies A guide for reducing operating costs and improving sustainability including Foreword 2 A five-step plan for institutions plus 205 initiatives to help get you Introduction 3 started Museums, Galleries and Energy Benefits of Change Survival strategies for museums & art galleries 4 Legislation Environmental Control and Collections Care Standards Five simple steps – A survival strategy for your institution 9 Step #1 Determine your baseline and appropriate level of refurbishment 10 Step #2 Review your building maintenance, housekeeping and energy purchasing 14 Sustainability makes good sense for museums. Step #3 Establish your targets and goals 18 A sustainable business is one that will survive and Step #4 Select your optimal upgrade initiatives 22 continue to benefit society. Vanessa Trevelyan, 2010 President of Museums Association Head of Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service Step #5 Make your survival strategy happen 50 Further information 54 Renaissance in the Regions Environmental Sustainability Initiatives 58 Acknowledgements and Contacts 60 Cover © Scott Frances 1 Foreword Introduction The UK sustainable development strategy The Green Museums programme in the Our Green Museums programme has Museums, Galleries and Benefits of Change “aims to enable all people throughout the North West is part of a nationwide fabric focussed on empowering members of staff world to satisfy their basic needs and enjoy of initiatives and projects developed and at all levels to bring about organisational Energy Improving energy efficiency and acting Meet the needs a better quality of life without compromising supported through Renaissance in the change. -

Places of Worship

Places of Worship Buddhism Manchester Buddhist Centre 16 – 20 Turner Street Manchester M4 1DZ -‘Clear Vision Trust’ arranges guided visits to the Buddhist Centre.0161 8399579 email [email protected] and publishes resources for KS1, KS2 and KS3 http://www.clear-vision.org/Schools/Teachers/teacher-info.aspxManchester includes Fo Kuang Buddhist Centre, 540 Stretford Road, Manchester M16 9AF Contact Irene Mann (Wai Lin) 07759828801 at Buddhist Temple and the Chinese Cultural/community centre. They are very welcoming and can accommodate up to 200 pupils at a time. Premises include kitchens, classrooms, a prayer Hall, 2 other shrines and a shrine for the ashes of the ancestors. They also have contacts with the Chinese Arts Centre and can provide artists to work with pupils. Chinese Arts Centre Market Buildings, Thomas Street Manchester M41EU 0161 832 7271/7280 fax0161 832 7513 www.chinese-arts-centre.org Northwich Buddhists http://www.meditationincheshire.org/resident-teacher Odiyana Buddhist Centre, The Heysoms, 163 Chester Road, Northwich, CW8 4AQ Christianity West Street Crewe Baptist Tel 01270 216838 [email protected] Sandbach Baptist Church Wheelock Heath Tel 01270876072 Chester Cathedral Contact Education Officer, 12, Abbey Square, Chester, CH12HU. Tel. 01244 324756 email [email protected] www.chestercathedral.com Manchester Cathedral Education Officer, Manchester, M31SX Tel 0161 833 2220 email [email protected] Liverpool Anglican Cathedral - St James Mount, Liverpool, L17AZ Anglican cathedral 0151 702 7210 Education Officer [email protected] Tel. 0151 709 6271 www.liverpoolcathedral.org.uk Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King (Roman Catholic) Miss May Gillet, Education Officer, Cathedral House, Mount Pleasant, Liverpool, L35TQ, Tel. -

Islamic Activities - Rabi Ul Awwal

Islamic Activities - Rabi ul Awwal Sunnah’s of the Prophet(pbuh) The last week of the term was the start of the Islamic Month Rabi ul Awwal. The month in which many believe the Prophet (sallalahu Alayhi Wasalam) was born and passed away. At MIHSG we try to highlight the importance of each Islamic month and its significance in Islamic history. During this week we put up posters highlighting different Sunnah’s of the Prophet (Saw) as well as the characteristics of the Prophet (Saw). Story of Maryam (AS) and Prophet Isa (AS) Every day before Asr Salah, pupils were presented with the story of Maryam (AS) and Prophet Isa (AS) so pupils could drive Islamic lessons and make comparisons to the Christian narrative they would hear about during this time. This was followed up by a whole school Jummah prayer on the last day of term with Br Jahengir (Imam from Khizra mosque) doing the khutbah on Maryam (AS) and Prophet Isa (AS). The Jummah prayer was beautifully led and benefitted by all. Sunnah Challenge As part of the last day of term activities pupils were presented with a presentation on the life of the Prophet (SAW) and the Sunnahs of the Prophet (Saw). Rabi ul Awwal is a month for Muslims to learn more about the Prophet (Saw)’s life and characteristics as well as completing Sunnah’s of the Prophet. Pupils were given a worksheet to carry out one act of Sunnah every day of the holidays and for parents to sign what they have done; and pupils will be presented with a prize. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Executive, 11/03/2020 10:00

Public Document Pack Executive Date: Wednesday, 11 March 2020 Time: 10.00 am Venue: Council Antechamber, Level 2, Town Hall Extension Everyone is welcome to attend this Executive meeting. Access to the Council Antechamber Public access to the Antechamber is via the Council Chamber on Level 2 of the Town Hall Extension, using the lift or stairs in the lobby of the Mount Street entrance to the Extension. That lobby can also be reached from the St. Peter’s Square entrance and from Library Walk. There is no public access from the Lloyd Street entrances of the Extension. Filming and broadcast of the meeting Meetings of the Executive are ‘webcast’. These meetings are filmed and broadcast live on the Internet. If you attend this meeting you should be aware that you might be filmed and included in that transmission. Membership of the Executive Councillors Leese (Chair), Akbar, Bridges, Craig, N Murphy, S Murphy, Ollerhead, Rahman, Stogia and Richards Membership of the Consultative Panel Councillors Karney, Leech, M Sharif Mahamed, Sheikh, Midgley, Ilyas, Taylor and S Judge The Consultative Panel has a standing invitation to attend meetings of the Executive. The Members of the Panel may speak at these meetings but cannot vote on the decision taken at the meetings. Executive Agenda 1. Appeals To consider any appeals from the public against refusal to allow inspection of background documents and/or the inclusion of items in the confidential part of the agenda. 2. Interests To allow Members an opportunity to [a] declare any personal, prejudicial or disclosable pecuniary interests they might have in any items which appear on this agenda; and [b] record any items from which they are precluded from voting as a result of Council Tax/Council rent arrears; [c] the existence and nature of party whipping arrangements in respect of any item to be considered at this meeting. -

News Release Embargoed Until 5Pm on Wednesday 11 October 2017

News release Embargoed until 5pm on Wednesday 11 October 2017 Alistair Hudson appointed as new Director for Manchester Art Gallery and The University of Manchester’s Whitworth The University of Manchester and Manchester City Council have today announced that Alistair Hudson, currently Director of the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (mima), will be the new Director of Manchester Art Gallery and the Whitworth. Alistair will take up his role in the New Year. He succeeds Maria Balshaw at the Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery following her appointment as Director of Tate earlier this year. He brings with him a wealth of experience at the forefront of the culture sector and a strong record of championing art as a tool for social change and education. During the last three years as Director at mima, he set out the institution’s vision as a ‘Useful Museum’, successfully engaging its local communities and responding to the town’s industrial heritage, as well as placing it amongst the most prestigious galleries in the UK. Alistair began his career at the Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London (1994-2000), before joining The Government Art Collection (2000-04) where, as Projects Curator, he devised a public art strategy for the new Home Office building with Liam Gillick. As Deputy Director of Grizedale Arts (2004-14) in the Lake District, he helped the institution gain critical acclaim for its radical approaches to working with artists and communities, based on the idea that art should be useful and not just an object of contemplation. Outside of these roles he is also Chair of Culture Forum North, an open network of partnerships between Higher Education and the cultural sector across the North and co-director of the Asociación de Arte Útil with Tania Bruguera. -

Manchester Publishing Date: 2007-11-01 | Country Code: Gb 1

ADVERTISING AREA REACH THE TRAVELLER! MANCHESTER PUBLISHING DATE: 2007-11-01 | COUNTRY CODE: GB 1. DURING PLANNING 2. DURING PREPARATION Contents: The City, Do & See, Eating, Bars & Nightlife, Shopping, Cafés, Sleeping, Essential Information 3. DURING THE TRIP Advertise under these headings: The City, Do & See, Cafés, Eating, Bars & Nightlife, Shopping, Sleeping, Essential Information, maps Copyright © 2007 Fastcheck AB. All rights reserved. For more information visit: www.arrivalguides.com SPACE Do you want to reach this audience? Contact Fastcheck FOR E-mail: [email protected] RENT Tel: +46 31 711 03 90 Population: 2.6 million inhabitants Currency: British Pound, £1 = 100 pence Opening hours: Shops are usually open on Monday - Friday 10 a.m. – 8 p.m., Saturday 9 a.m. – 7 p.m., Sunday 11 a.m. – 5 p.m. Internet: www.visitmanchester.com/travel www.manchester2002-uk.com/whatsnew www.manchester.world-guides.com Newspapers: The Guardian Manchester Evening News Manchester Metro News (free) Emergency numbers: 112, 999 Tourist information: Manchester Tourist Information Centre is in the Town Hall Extension, St. Peter’s Square. Tel: +44 (0)161 234 3157 / 3158. There are also tourist offices at 101 Liverpool Road and in the arrival hall at the airport. MANCHESTER These days, Manchester is famous for more than just football and rock n’ roll – even if these activities are still very important. Cool bars and shops nestle side by side in suburbs such as Northern Quarter, Castlefield and Gay Village. DESTINATION: MANCHESTER |PUBLISHING DATE: 2007-11-01 THE CITY city which compares well with other international cities. Wherever you are you’ll find the historical waterways. -

Press Release Template.Indd

Wednesday 28 April 2021 UNVEILING OF TURNER PRIZE WINNER’S NEW WORK EXPLORING THE LONG-LOST VOICES OF MANCHESTER’S JEWISH COMMUNITY Turner Prize-winning artist Laure Prouvost will unveil a major new work that will transform The Ladies' Gallery in the historic synagogue of the Manchester Jewish Museum. The long waited, weighted gathering, co-commissioned by Manchester International Festival and the newly renovated Manchester Jewish Museum, will premiere at MIF21 on 2 July 2021. The immersive installation will consist of a new film, shot inside the gallery and in the surrounding Cheetham Hill area, inspired by the museum’s history as a former Spanish and Portuguese synagogue. Laure Prouvost has explored the museum’s extensive collection to discover the stories behind past congregants of the synagogue, unearthing the long-lost voices of the women who once found comfort and community within its walls. Prouvost’s films are often accompanied by objects which evoke its themes and imagery. For this work, materials that have been created while working with the Museum’s resident Women’s Textiles Group will be incorporated within the installation alongside the new film, capturing the voices of modern women in the local community together with those of the women who once gathered in the synagogue’s Ladies' Gallery. The installation will feature as a major part of the reopening of the newly redeveloped Manchester Jewish Museum on 2 July, following a two-year £6 million Capital Development project, partly funded by a £2.89m National Heritage Lottery Fund grant. As well as the restoration of its 1874 Spanish and Portuguese synagogue, the new museum will include a new gallery, café, shop and learning studio, and kitchen where schools and community groups can develop a greater understanding of the Jewish way of life. -

Anglo-Jewry's Experience of Secondary Education

Anglo-Jewry’s Experience of Secondary Education from the 1830s until 1920 Emma Tanya Harris A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University College London London 2007 1 UMI Number: U592088 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592088 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract of Thesis This thesis examines the birth of secondary education for Jews in England, focusing on the middle classes as defined in the text. This study explores various types of secondary education that are categorised under one of two generic terms - Jewish secondary education or secondary education for Jews. The former describes institutions, offered by individual Jews, which provided a blend of religious and/or secular education. The latter focuses on non-Jewish schools which accepted Jews (and some which did not but were, nevertheless, attended by Jews). Whilst this work emphasises London and its environs, other areas of Jewish residence, both major and minor, are also investigated. -

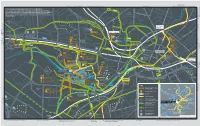

Getting to Salford Quays Map V15 December 2015

Trams to Bury, Ú Ú Ú Ú Ú Ú Bolton Trains to Wigan Trains to Bolton and Preston Prestwich Oldham and Rochdale Rochdale Rochdale to Trains B U R © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 0100022610. B Y R T Use of this data is subject to terms and conditions: You are granted a non-exclusive, royalty O NCN6 E A LL E D E and Leeds free, revocable licence solely to view the Licensed Data for non-commercial purposes for the R W D M T S O D N A period during which Transport for Greater Manchester makes it available; you are not permitted R S T R Lower E O R C BRO to copy, sub-license, distribute, sell or otherwise make available the Licensed Data to third E D UG W R E A HT T O Broughton ON S R LA parties in any form; and third party rights to enforce the terms of this licence shall be reserved NE E L to Ordnance Survey W L L R I O A O H D L N R A D C C D Ú N A A K O O IC M S T R R T A T H E EC G D A H E U E CL ROAD ES LD O R E T R O R F E B R Ellesmere BR E O G A H R D C Park O D G A Pendleton A O R E D R S River A Ú T Ir Oldham Buile Hill Park R wel T E W E l E D L D T Manchester A OL E U NE LES A D LA ECC C H E S I Victoria G T T E C ED Salford O E Peel Park E B S R F L E L L R A T A S A Shopping H T C S T K N F O R G Centre K I T A D W IL R Victoria A NCN55 T Salford Crescent S S O O R J2 Y M R A M602 to M60/M61/M62/M6 bus connections to bus connections to Ú I W L Salford Royal T L L L R E Salford Quays (for MediaCityUK) H Salford Quays (for MediaCityUK) R A A O Hospital T S M Seedley Y A N N T A E D T H E A E E D S L L R -

Leading Artists Commissioned for Manchester International Festival

Press Release LEADING ARTISTS COMMISSIONED FOR MANCHESTER INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL High-res images are available to download via: https://press.mif.co.uk/ New commissions by Forensic Architecture, Laure Prouvost, Deborah Warner, Hans Ulrich Obrist with Lemn Sissay, Ibrahim Mahama, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Rashid Rana, Cephas Williams, Marta Minujín and Christine Sun Kim were announced today as part of the programme for Manchester International Festival 2021. MIF21 returns from 1-18 July with a programme of original new work by artists from all over the world. Events will take place safely in indoor and outdoor locations across Greater Manchester, including the first ever work on the construction site of The Factory, the world-class arts space that will be MIF’s future home. A rich online offer will provide a window into the Festival wherever audiences are, including livestreams and work created especially for the digital realm. Highlights of the programme include: a major exhibition to mark the 10th anniversary of Forensic Architecture; a new collaboration between Hans Ulrich Obrist and Lemn Sissay exploring the poet as artist and the artist as poet; Cephas Williams’ Portrait of Black Britain; Deborah Warner’s sound and light installation Arcadia allows the first access to The Factory site; and a new commission by Laure Prouvost for the redeveloped Manchester Jewish Museum site. Manchester International Festival Artistic Director & Chief Executive, John McGrath says: “MIF has always been a Festival like no other – with almost all the work being created especially for us in the months and years leading up to each Festival edition. But who would have guessed two years ago what a changed world the artists making work for our 2021 Festival would be working in?” “I am delighted to be revealing the projects that we will be presenting from 1-18 July this year – a truly international programme of work made in the heat of the past year and a vibrant response to our times. -

Gaskell Society Newsletters Index of Authors and Subjects

GASKELL SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS INDEX OF AUTHORS AND SUBJECTS. Aber. Pen y Bryn. Lindsay, Jean. Elizabeth and William’s Honeymoon in Aber, September 1832. [illus.] No.25 March 1998. Adlington Hall, Cheshire. Yarrow, Philip J. The Gaskell Society’s outing – 8 October 1989. No.9 March 1990. Alfrick Court, Worcestershire, [home of Marianne Holland]. Alston, Jean. Gaskell study tour to Worcester, Bromyard and surrounding areas-20 to 22 May 2014. [illus.] No.58. Autumn 2014. Allan, Janet. The Gaskells’ bequests. No.32. Autumn 2001. The Gaskells’ shawls. No.33. Spring 2002. Allan, Robin. Elizabeth Gaskell and Rome. No.55. Spring 2013. Alps. Lingard, Christine. Primitive, cheap and bracing: the Gaskells in the Alps. No.58. Autumn 2014. Alston, Jean. Gaskell-Nightingale tour, 30 May 2012. No.54. Autumn 2012. Gaskell study tour to Worcester, Bromyard and surrounding areas-20 to 22 May 2014. No.58. Autumn 2014. Marianne and her family in Worcestershire. No.59. Spring 2015. Tour in Scottish Lowlands, 7-11 July 2008. [illus.] No.46. Autumn 2008. Una Box, who died 14 November 2010, aged 71 years, [obituary]. No.51. Spring 2011. Visit to Ashbourne, Alstonefield and the Hope House Costume Museum, [Derbyshire]. 5th July 2006. No.42. Autumn 2006. Alstonefield, Derbyshire. Alston, Jean. Visit to Ashbourne, Alstonefield and the Hope House Costume Museum, 5th July 2006. No.42. Autumn 2006. American Civil War. Smith, Muriel. Elizabeth Gaskell and the American Civil War. No.36. Autumn 2003. Andreansky, Maria. Luce, Stella. Maria Andreansky 1910-2011 [obituary]. [illus.] No.53. Spring 2012. Anne Hathaway’s Cottage see Stratford-upon-Avon. -

07 Art on the Edge

Creativetourist.com is a monthly online magazine and series of city guides that have been put together 01 INTRODUCTION by Manchester Museums Consortium. This group of nine museums and galleries in Manchester are separate 02 SMALL WONDERS venues that share a dual vision: the desire to stage intelligent, thought- provoking and outward looking 03 ANIMAL MAGIC exhibitions and events; and to celebrate the city in which they live, work and play. Twice a year, Creativetourist. 04 RUN OF THE MILL com publishes insider guides to the city – uncovering not just galleries and museums but shops, bars, leftfield 05 GENE GENIUS events, restaurants and nights out that are distinctly, uniquely Mancunian. This guide has been developed in 06 SUMMER SPECIALS association with World Class Service. ON THE HOOF 07 ART ON THE EDGE 08 RAIN OR SHINE 09 FiELD TRIPS 10 TOP FIVES 11 FOR BABIES (AND THEIR PARENTS) 12 FOR TODDLERS 13 STUFF FOR KIDS 14 UNDER 18s ONLY 15 BOOK YOUR STAY This project would not be possible without the support of: It’S SUMMERTIME IN MANCHESTER, AND there’S LOTS TO DO. FROM AL FRESCO FILM TO MUSICAL SHIPPING CONTAINERS, FROM A NEW LiVING WORLDS GALLERY TO A CELEBRATION OF FROGS, FROM TALES OF INDUSTRIAL LIFE TO BUILDING YOUR OWN STRAND OF DNA: THIS IS YOUR INDISPENSABLE GUIDE TO THE MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES, THE PARKS AND GARDENS, THE KID- FRIENDLY CAFÉS, SHOPS AND 01 HOTELS OF MANCHESTER. You wouldn’t know it from the most innovative and exciting work 9 must be accompanied by an adult, reading the broadsheets, but the most they can do.