Methods and Tools for Transcribing Electroacoustic Music Pierre Couprie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

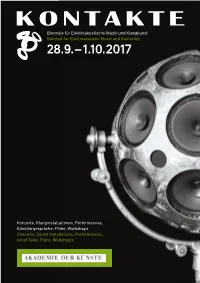

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

Ambiant Creativity Mo Fr Workshop Concerts Lectures Discussions

workshop concerts lectures discussions ambiant creativity »digital composition« March 14-18 2011 mo fr jérôme bertholon sebastian berweck ludger brümmer claude cadoz omer chatziserif johannes kreidler damian marhulets thomas a. troge iannis zannos // program thursday, march 17th digital creativity 6 pm, Lecture // Caught in the Middle: The Interpreter in the Digital Age and Sebastian Berweck contemporary ZKM_Vortragssaal music 6.45 pm, IMA | lab // National Styles in Electro- acoustic Music? thomas a. troged- Stipends of “Ambiant Creativity” and Sebastian fdfd Berweck ZKM_Vortragssaal 8 pm, Concert // Interactive Creativity with Sebastian Berweck (Pianist, Performer), works by Ludger Brümmer, Johannes Kreidler, Enno Poppe, Terry Riley, Giacinto Scelsi ZKM_Kubus friday, march 18th 6 pm, Lecture // New Technologies and Musical Creations Johannes Kreidler ZKM_Vortragsaal 6.45 pm, Round Table // What to Expect? Hopes and Problems of Technological Driven Art Ludger Brümmer, Claude Cadoz, Johannes Kreidler, Thomas A. Troge, Iannis Zannos ZKM_Vortragssaal 8 pm, Concert // Spatial Creativity, works by Jérôme Bertholon, Ludger Brümmer, Claude Cadoz, Omer Chatziserif, Damian Marhulets, Iannis Zannos ZKM_Kubus 10pm, Night Concert // Audiovisual Creativity with audiovisual compositions and dj- sets by dj deepthought and Damian Marhulets ZKM_Musikbalkon // the project “ambiant creativity” The “Ambiant Creativity” project aims to promote the potential of interdisciplinary coopera- tion in the arts with modern technology, and its relevance at the European Level. The results and events are opened to the general public. The project is a European Project funded with support from the European Commission under the Culture Program. It started on October, 2009 for a duration of two years. The partnership groups ACROE in France, ZKM | Karlsruhe in Germany and the Ionian University in Greece. -

5. Iannis Xenakis

5. Iannis Xenakis „C’était deux ou trois ans après l’invasion russe en Tchécoslovaquie. Je suis tombé amoreux de la musique de Varèse et de Xenakis. Je me demande pourquoi […].“ Milan Kundera: Une rencontre129 Recepce a teoretická reflexe tvorby Iannise Xenakise v našem prostředí není nijak významná. Když pomineme texty a studie, které jsou součástí lexik, vysokoškolských skript a obecných přehledů dějin hudby, stojí za zmínku především stať Milana Kundery Iannis Xenakis, prorok necitovosti. Ačkoliv se nejedná o muzikologickou studii, jejímu autorovi se (jako mnohokrát) daří popsat konkrétní rysy skladatelovy tvorby s daleko větší přesností, než jaké by byl zřejmě schopen muzikolog. Ve francouzské verzi se text objevuje v roce 1980 pod názvem Le refus intégral de l’héritage ou Iannis Xenakis (Naprosté odmítnutí dědictví aneb Iannis Xenakis). O to cennější je skutečnost, že se Kundera k původnímu textu vrací v nově vydané sbírce esejů Une rencontre. Přiznává v něm, že v hudbě Varèse a Xenakise nalezl zvláštní útěchu, která spočívá ve smíření s nevyhnutelností konečnosti. Prorokem necitovosti nazval Carl Gustav Jung Jamese Joyce ve své analýze Odyssea. Zde také přichází s tezí, že citovost je nadstavbou brutality. Vyvážení této sentimentality přinášejí proroci asentimentality, podle Junga Joyce, podle Kundery Xenakis. Podle Kundery hudba vždy svojí subjektivitou čelila objektivitě světa. Existují však okamžiky, kdy se subjektivita nebo také emocionalita (která za normálních okolností vrací člověka k jeho podstatě a zmírňuje chlad intelektu) stává nástrojem brutality a zla. V takových okamžicích se naopak objektivní hudba stává krásou, která smývá nánosy emocionality a tlumí barbarství sentimentu. Xenakisův postoj k historii hudby je podle Kundery radikálně odmítavý. -

Electroacoustic Music Studios BEAST Concerts in 1994

Electroacoustic Music Studios BEAST Concerts in 1994 Norwich, 7th February Manchester, 22nd February Nottingham, 18th March More about BEAST concerts:- The Acousmatic Experience, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7th - 10th April Concert news Edinburgh, Scotland, 17th May Concert archives London, 11th November Birmingham, 13th November Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, Huddersfield, 18th November Rumours, Birmingham, England, 4th - 5th December 7th February 1994 Norwich, England Sound diffusion for the Sonic Arts Network 22nd February 1994 Manchester, England Sound diffusion for the Sonic Arts Network 18th March 1994 Nottingham, England Sound diffusion for the Sonic Arts Network The Acousmatic Experience, 7th - 10th April 1994 Amsterdam, The Netherlands A series of concerts performed by BEAST. 7th April 8.15 pm Karlheinz Stockhausen - Hymnen 8th April 8.15 pm 1. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: toccata 2. Jonty Harrison - Pair/Impair 3. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: "Qu'ai-je entendu" 4. Kees Tazelaar - Paradigma 5. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: "Les Agrémants" 6. Barry Truax - Basilica 7. Yves Daoust - Suite Baroque: "L'Extase" 8. Denis Smalley - Wind Chimes 9th April 2 pm 1. Barry Truax - The Blind Man 2. Bernard Parmegiani - Dedans/Dehors 3. Francis Dhomont - Espace/Escape 4. Jan Boerman - Composition 1972 8.15 pm 1. Michel Chion - Requiem 2. Robert Normandeau - Mémoires Vives 3. Bernard Parmegiani - Rouge-Mort: Thanatos 4. Erik M. Karlsson - La Disparition de l'Azur 10th April 2 pm 1. Pierre Schaeffer & Pierre Henry - Synphonie Pour un Homme Seul 2. John Oswald - Plunderphonics [extract] 3. Carl Stone - Hop Ken 4. Mark Wingate - Ode to the South-Facing Form 5. Erik M. Karlsson - Anchoring Arrows 8 pm 1. -

Music Inspired by Astronomy, Organized by Topic an Annotated Listing by Andrew Fraknoi

Music Inspired by Astronomy, Organized by Topic An Annotated Listing by Andrew Fraknoi © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Used with permission. Borresen: At Uranienborg Cage: Atlas Eclipticalis Glass: Orion Connections between astronomy and music have been proposed since the time of the ancient Greeks. This annotated listing of both classical and popular music inspired by astronomy restricts itself to music that has connections to real science -- not just an astronomical term or two in the title or lyrics. For example, we do not list Gustav Holst’s popular symphonic suite The Planets, because it draws its inspiration from the astrological, and not astronomical, characteristics of the worlds in the solar system. Similarly, songs like Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun” or the Beatles’ “Across the Universe” just don’t contain enough serious astronomy to make it into our guide. When possible, we give links to a CD and a YouTube recording or explanation for each piece. The music is arranged in categories by astronomical topic, from asteroids to Venus. Additions to this list are most welcome (as long as they follow the above guidelines); please send them to the author at: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu Table of Contents Asteroids Meteors and Meteorites Astronomers Moon Astronomy in General Nebulae Black Holes Physics Related to Astronomy Calendar, Time, Seasons Planets (in General) Comets Pluto Constellations Saturn Cosmology SETI (Search for Intelligent Life Out There) Earth Sky Phenomena Eclipses Space Travel Einstein Star Clusters Exoplanets Stars and Stellar Evolution Galaxies and Quasars Sun History of Astronomy Telescopes and Observatories Jupiter Venus Mars 1 Asteroids Coates, Gloria Among the Asteroids on At Midnight (on Tzadik). -

! ! ! Universidade!Estadual!Paulista! Júlio!De!Mesquita!Filho! Instituto!De

! ! ! Universidade!Estadual!Paulista! Júlio!de!Mesquita!Filho! Instituto!de!Artes! Departamento!de!Música! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! GEORGE!OLOF!DE!FREITAS!ALVESKOG! ! ! ! ! Escritura!do!Espaço!na!Música!Eletroacústica! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! São!Paulo! 2016! ! ! ! ! GEORGE!OLOF!DE!FREITAS!ALVESKOG! ! ! ! ! Escritura!do!Espaço!na!Música!Eletroacústica! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dissertação! apresentada! ao! Programa! de! PósEgraduação! em! Música! do! Instituto! de! Artes! da! Universidade! Estadual! Paulista,! Linha! de! Pesquisa! Epistemologia! e! Práxis! do! Processo! Criativo,! como! exigência! parcial! para! a! obtenção! do! título! de! Mestre! em! Música,! sob! orientação! do! Prof.! Dr.!Florivaldo!Menezes!Filho.! ! ! ! ! São!Paulo! 2016! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ficha!catalográfica!preparada!pelo!Serviço!de!Biblioteca!e!Documentação!do!Instituto!de!Artes!da! UNESP! ! ! ! A474e! Alveskog,!George!Olof!De!Freitas! Escritura!do!espaço!na!música!eletroacústica!!/!George!Olof!De! Freitas!Alveskog.!E!São!Paulo,!2016.! 119!f.!:!il.!color.!! ! Orientador:!Prof.!Dr.!Florivaldo!Menezes!Filho! Dissertação!(Mestrado!em!Música)!–!Universidade!Estadual! Paulista!“Julio!de!Mesquita!Filho”,!Instituto!de!Artes.! ! 1.!Musica!por!computador.!!2.!Composição!(Música).!3.!Música! –!Análise,!apreciação.!I.!Menezes!Filho,!Florivaldo.!II.!Universidade! Estadual!Paulista,!Instituto!de!Artes.!III.!Título.! ! CDD!789.99!!!! ! ! ! ! GEORGE!OLOF!DE!FREITAS!ALVESKOG! Escritura!do!espaço!na!música!eletroacústica! Dissertação aprovada como requisito -

A History of Electronic Music Pioneers David Dunn

A HISTORY OF ELECTRONIC MUSIC PIONEERS DAVID DUNN D a v i d D u n n “When intellectual formulations are treated simply renewal in the electronic reconstruction of archaic by relegating them to the past and permitting the perception. simple passage of time to substitute for development, It is specifically a concern for the expansion of the suspicion is justified that such formulations have human perception through a technological strate- not really been mastered, but rather they are being gem that links those tumultuous years of aesthetic suppressed.” and technical experimentation with the 20th cen- —Theodor W. Adorno tury history of modernist exploration of electronic potentials, primarily exemplified by the lineage of “It is the historical necessity, if there is a historical artistic research initiated by electronic sound and necessity in history, that a new decade of electronic music experimentation beginning as far back as television should follow to the past decade of elec- 1906 with the invention of the Telharmonium. This tronic music.” essay traces some of that early history and its —Nam June Paik (1965) implications for our current historical predicament. The other essential argument put forth here is that a more recent period of video experimentation, I N T R O D U C T I O N : beginning in the 1960's, is only one of the later chapters in a history of failed utopianism that Historical facts reinforce the obvious realization dominates the artistic exploration and use of tech- that the major cultural impetus which spawned nology throughout the 20th century. video image experimentation was the American The following pages present an historical context Sixties. -

MAT 200B F14 Syllabus

__________________________________ MAT 200B Music and Technology Fall 2014, Tuesday-Thursday 3-5 PM Studio Xenakis, Room 2215, Music Building Professor Curtis Roads, Elings Hall 2203 University of California, Santa Barbara Office telephone (805) 893-2932, [email protected] Teaching assistant: Mr. Aaron Demby Jones, [email protected] Textbook: The Computer Music Tutorial (1996) by Curtis Roads, The MIT Press ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Week 1 Orientation; Historical overview of electronic music 2 Oct Introductions and orientation The legend of electronic music I Assignment Read "The great opening up of music to all sounds," pages 21-62 of Electric Sound by Joel Chadabe. Read “Evaluating audio projects” Quiz 1 next Thursday on the Chadabe text Final project assignment Choose one of three options: PAPER, STUDIO PROJECT, or PROGRAMMING/MAKING, and realize a final project in consultation with the instructor. All projects are presented in class. Here are some possible projects. 1. PAPER Present an historical or technical paper. An historical paper might focus on, for example, a pioneer of electronic music, such as Clara Rockmore, Theremin, Xenakis, Hiller, Stockhausen, Varèse, Bebe Barron, etc. A technical paper should focus on a topic related to digital audio or music, such as audio analysis, digital sound formats, Internet audio, digital rights management, musical feature extraction, high-resolution audio, etc. (10-20 double-spaced pages typical) 2. STUDIO PROJECT USING MULTIRACK RECORDING, EDITING, MIXING The studio project could be original music or a soundtrack for a video project, an audio documentary, audio play, sound art, environmental, or ambient piece 3. PROGRAMMING/MAKING PROJECT Develop software and or hardware related to digital audio and music using Matlab, SuperCollider, Csound, C++, Java, Max/MSP, Python, etc. -

6.2. the Social Meaning of Accelerated Noise in Speedy Capitalism

6.2. The social meaning of accelerated noise in speedy capitalism Ion Andoni del Amo Castro1, Arkaitz Letamendia Onzain2 and Jason Diaux González3 Abstract In this work, we study the parallelism between the acceleration of the rotation of the Capital and the hastening of the rhythm of music. The modernity was the time for the development of Total Artworks, able to reflect the essence of their unhurried time. Beethoven could be considered as an example of it: the era of Total Sound. When the 20th century began, Italian futurists perceived the arrival of noise like a form of art; they claimed for the velocity, the energy and the rush of the industrial city. Progressively, the rhythm of the music becomes more accelerated. On the second half of the century, electronic, punk, and industrial music makes explicit the noise (and the speediness) of their own time. But this noise aspires to be sound, even if lack of communication is what it wants to communicate: the Sound of Noise. Today, accelerated capitalism of the 21st century turns into the fragmentation of the historical time, and together with its postmodern logic, the cultural products get empty: the era of Total Noise. As a result, nowadays, the social meaning of music is not about differentiation or strong construction of group (sub)cultural identities. Now its main function is that of sharing, providing a common language for sociality. Keywords: capitalism, music, noise, acceleration, subcultures. 1. The essence of modernity and total sound 1st Premise: Total Art, art which captures the essence of its historical age; works of art which reflect their periods’ profound, defining characteristics. -

Digital Cultures Listening Lists

Digital Cultures: Music Recommended Listening and Reading (Prof Andrew Hugill) The following long (but nowhere near long enough to cover everything) listening list not only illustrates some of the key ideas about modernism and postmodernism, structuralism and deconstruction, but also adds up to a mini-history of the evolution of electronic and electroacoustic music in the 20th Century. Some brief descriptive notes are included to indicate the salient features, but there is no substitute for careful and repeated listening, with perhaps some attempt to analyse what is heard. It should be remembered that Modernism and Postmodernism are not musical styles, nor words that artists and composers use to describe their work, but rather terms from critical and cultural theory that seem to sum up broad tendencies in art. In fact, all the pieces below will probably be heard to exhibit characteristics of both ‘isms’. Some useful questions to ask when listening are: what is the artist’s intention? How well is it realized? What is the cultural context for the work? What are its compositional techniques? What is the musical language? Pierre Schaeffer ‘Etude aux chemins de fer’ from ‘Cinq études de bruits’ (1948) on OHM: the early gurus of electronic music: 1948-1980. Roslyn, New York: Ellipsis Arts. This was the first time recorded sound was assembled into a musical composition. The sounds included steam engines, whistles and railway noises. Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry Symphonie pour un homme seul (1950) on Pierre Schaeffer: l’oeuvre musicale EMF EM114. A 12-movement musical account of a man’s day using recorded sounds. -

The Granular Connection (Xenakis, Vaggione, Di Scipio...) Makis Solomos

The granular connection (Xenakis, Vaggione, Di Scipio...) Makis Solomos To cite this version: Makis Solomos. The granular connection (Xenakis, Vaggione, Di Scipio...). Symposium The Creative and Scientific Legacies of Iannis Xenakis International Symposium, 2006, Canada. hal-00770088 HAL Id: hal-00770088 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00770088 Submitted on 7 Jan 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The granular connection (Xenakis, Vaggione, Di Scipio…) Makis Solomos Université Montpellier 3, Institut Universitaire de France [email protected] Symposium The Creative and Scientific Legacies of Iannis Xenakis International Symposium, organized by James Harley (University of Guelph), Michael Duschenes (Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics), Thomas Salisbury (Fields Institute for Research in Mathematical Sciences), June 2006 Abstract. This paper examines: 1) the way Xenakis introduced the granular paradigm; 2) some elements for the history of the granular paradigm (especially the work of Horacio Vaggione and Agostino Di Scipio). NB. The English version of this article has not been revised (except 2.2) Many ways start from or go through Xenakis. One of these ways is the granular paradigm1. In this paper, I will start from Xenakis, suggesting that, in his aesthetic, this approach is a “theory” in the ancient meaning of the word, and searching for the constituent elements of this “vision”.