Indian Snakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Genus Lycodon)

Zoologica Scripta Multilocus phylogeny reveals unexpected diversification patterns in Asian wolf snakes (genus Lycodon) CAMERON D. SILER,CARL H. OLIVEROS,ANSSI SANTANEN &RAFE M. BROWN Submitted: 6 September 2012 Siler, C. D., Oliveros, C. H., Santanen, A., Brown, R. M. (2013). Multilocus phylogeny Accepted: 8 December 2012 reveals unexpected diversification patterns in Asian wolf snakes (genus Lycodon). —Zoologica doi:10.1111/zsc.12007 Scripta, 42, 262–277. The diverse group of Asian wolf snakes of the genus Lycodon represents one of many poorly understood radiations of advanced snakes in the superfamily Colubroidea. Outside of three species having previously been represented in higher-level phylogenetic analyses, nothing is known of the relationships among species in this unique, moderately diverse, group. The genus occurs widely from central to Southeast Asia, and contains both widespread species to forms that are endemic to small islands. One-third of the diversity is found in the Philippine archipelago. Both morphological similarity and highly variable diagnostic characters have contributed to confusion over species-level diversity. Additionally, the placement of the genus among genera in the subfamily Colubrinae remains uncertain, although previous studies have supported a close relationship with the genus Dinodon. In this study, we provide the first estimate of phylogenetic relationships within the genus Lycodon using a new multi- locus data set. We provide statistical tests of monophyly based on biogeographic, morpho- logical and taxonomic hypotheses. With few exceptions, we are able to reject many of these hypotheses, indicating a need for taxonomic revisions and a reconsideration of the group's biogeography. Mapping of color patterns on our preferred phylogenetic tree suggests that banded and blotched types have evolved on multiple occasions in the history of the genus, whereas the solid-color (and possibly speckled) morphotype color patterns evolved only once. -

Venom Protein of the Haematotoxic Snakes Cryptelytrops Albolabris

S HORT REPORT ScienceAsia 37 (2011): 377–381 doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2011.37.377 Venom protein of the haematotoxic snakes Cryptelytrops albolabris, Calloselasma rhodostoma, and Daboia russelii siamensis Orawan Khow, Pannipa Chulasugandha∗, Narumol Pakmanee Research and Development Department, Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute, Patumwan, Bangkok 10330 Thailand ∗Corresponding author, e-mail: pannipa [email protected] Received 1 Dec 2010 Accepted 6 Sep 2011 ABSTRACT: The protein concentration and protein pattern of crude venoms of three major haematotoxic snakes of Thailand, Cryptelytrops albolabris (green pit viper), Calloselasma rhodostoma (Malayan pit viper), and Daboia russelii siamensis (Russell’s viper), were studied. The protein concentrations of all lots of venoms studied were comparable. The chromatograms, from reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography, of C. albolabris venom and C. rhodostoma venom were similar but they were different from the chromatogram of D. r. siamensis venom. C. rhodostoma venom showed the highest number of protein spots on 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis (pH gradient 3–10), followed by C. albolabris venom and D. r. siamensis venom, respectively. The protein spots of C. rhodostoma venom were used as reference proteins in matching for similar proteins of haematotoxic snakes. C. albolabris venom showed more similar protein spots to C. rhodostoma venom than D. r. siamensis venom. The minimum coagulant dose could not be determined in D. r. siamensis venom. KEYWORDS: 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis, reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography, minimum coag- ulant dose INTRODUCTION inducing defibrination 5–7. The venom of D. r. sia- mensis directly affects factor X and factor V of the In Thailand there are 163 snake species, 48 of which haemostatic system 8,9 . -

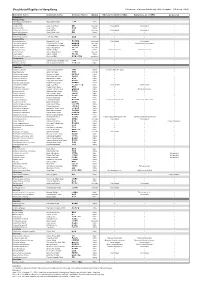

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

P. 1 AC27 Inf. 7 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement

AC27 Inf. 7 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-seventh meeting of the Animals Committee Veracruz (Mexico), 28 April – 3 May 2014 Species trade and conservation IUCN RED LIST ASSESSMENTS OF ASIAN SNAKE SPECIES [DECISION 16.104] 1. The attached information document has been submitted by IUCN (International Union for Conservation of * Nature) . It related to agenda item 19. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC27 Inf. 7 – p. 1 Global Species Programme Tel. +44 (0) 1223 277 966 219c Huntingdon Road Fax +44 (0) 1223 277 845 Cambridge CB3 ODL www.iucn.org United Kingdom IUCN Red List assessments of Asian snake species [Decision 16.104] 1. Introduction 2 2. Summary of published IUCN Red List assessments 3 a. Threats 3 b. Use and Trade 5 c. Overlap between international trade and intentional use being a threat 7 3. Further details on species for which international trade is a potential concern 8 a. Species accounts of threatened and Near Threatened species 8 i. Euprepiophis perlacea – Sichuan Rat Snake 9 ii. Orthriophis moellendorfi – Moellendorff's Trinket Snake 9 iii. Bungarus slowinskii – Red River Krait 10 iv. Laticauda semifasciata – Chinese Sea Snake 10 v. -

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong Family No. of Species Common Name Scientific Name Order TESTUDOFORMES Cheloniidae 4 Loggerhead Turtle Caretta caretta Green Turtle Chelonia mydas Hawksbill Turtle Eretmochelys imbricata Olive Ridley Turtle Lepidochelys olivacea Dermochelyidae 1 Leatherback Turtle Dermochelys coriacea Emydidae 1 Red-eared Slider * Trachemys scripta elegans Geoemydidae 3 Three-banded Box Turtle Cuora trifasciata Reeves' Turtle Mauremys reevesii Beale's Turtle Sacalia bealei Platysternidae 1 Big-headed Turtle Platysternon megacephalum Trionychidae 1 Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle Pelodiscus sinensis Order SQUAMATA Suborder LACERTILIA Agamidae 1 Changeable Lizard Calotes versicolor Lacertidae 1 Grass Lizard Takydromus sexlineatus ocellatus Scincidae 11 Chinese Forest Skink Ateuchosaurus chinensis Long-tailed Skink Eutropis longicaudata Chinese Skink Plestiodon chinensis chinensis Five-striped Blue-tailed Skink Plestiodon elegans Blue-tailed Skink Plestiodon quadrilineatus Vietnamese Five-lined Skink Plestiodon tamdaoensis Slender Forest Skink Scincella modesta Reeve's Smooth Skink Scincella reevesii Brown Forest Skink Sphenomorphus incognitus Indian Forest Skink Sphenomorphus indicus Chinese Waterside Skink Tropidophorus sinicus Varanidae 1 Common Water Monitor Varanus salvator Dibamidae 1 Bogadek's Burrowing Lizard Dibamus bogadeki Gekkonidae 8 Four-clawed Gecko Gehyra mutilata Chinese Gecko Gekko chinensis Tokay Gecko Gekko gecko Bowring's Gecko Hemidactylus bowringii Brook's Gecko* Hemidactylus brookii House Gecko* Hemidactylus -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt. -

An Epidemiological Study of Venomous Snake Bites: a Hospital Based Analysis

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE pISSN 0976 3325│eISSN 2229 6816 Open Access Article www.njcmindia.org An Epidemiological Study of Venomous Snake Bites: A Hospital Based Analysis Dipak H. Vora1, Jyoti H. Vora2 Financial Support: None declared ABSTRACT Conflict of Interest: None declared Copy Right: The Journal retains the Background & Objectives: This study was carried out to describe copyrights of this article. However, re- epidemiology of snake bite cases which were seen in a tertiary care production is permissible with due ac- hospital of Ahmedabad region so that the data provided will help knowledgement of the source. in estimating the envenoming in this region of India. How to cite this article: Methods: Total 50 cases of venomous snake bites were studied ret- Vora DH, Vora JH. An Epidemiological rospectively. These patients were admitted in the Medicine De- Study of Venomous Snake Bites: A partment of V.S. Hospital, Ahmedabad during the period from Hospital Based Analysis. Natl J Com- April 2008 to October 2009. munity Med 2019;10(8):474-478 Results: Maximum number of cases (66 %) was belonging to the Author’s Affiliation: age group 15-34 years. Male are having twice the incidence com- 1 Assistant Professor, Department of pare to the female (M: F ratio 2.12:1). Maximum cases were from Forensic Medicine, B. J. Medical Col- rural areas i.e. 72 %. In 66 % cases, snake bites occurred during lege; 2Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, SMT NHL Municipal night time. Most of the cases i.e. 82 % occurred during rainy sea- Medical College, Ahmedabad son. Elapid snake bites leading to neurotoxicity is common fol- lowed by viperidae induced vasculotoxicity and acute renal fail- Correspondence ure. -

New Records and an Updated Checklist of Amphibians and Snakes From

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Bonn zoological Bulletin - früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. Jahr/Year: 2021 Band/Volume: 70 Autor(en)/Author(s): Le Dzung Trung, Luong Anh Mai, Pham Cuong The, Phan Tien Quang, Nguyen Son Lan Hung, Ziegler Thomas, Nguyen Truong Quang Artikel/Article: New records and an updated checklist of amphibians and snakes from Tuyen Quang Province, Vietnam 201-219 Bonn zoological Bulletin 70 (1): 201–219 ISSN 2190–7307 2021 · Le D.T. et al. http://www.zoologicalbulletin.de https://doi.org/10.20363/BZB-2021.70.1.201 Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1DF3ECBF-A4B1-4C05-BC76-1E3C772B4637 New records and an updated checklist of amphibians and snakes from Tuyen Quang Province, Vietnam Dzung Trung Le1, Anh Mai Luong2, Cuong The Pham3, Tien Quang Phan4, Son Lan Hung Nguyen5, Thomas Ziegler6 & Truong Quang Nguyen7, * 1 Ministry of Education and Training, 35 Dai Co Viet Road, Hanoi, Vietnam 2, 5 Hanoi National University of Education, 136 Xuan Thuy Road, Hanoi, Vietnam 2, 3, 7 Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Graduate University of Science and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet Road, Hanoi, Vietnam 6 AG Zoologischer Garten Köln, Riehler Strasse 173, D-50735 Köln, Germany 6 Institut für Zoologie, Universität Köln, Zülpicher Strasse 47b, D-50674 Köln, Germany * Corresponding author: Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:2C2D01BA-E10E-48C5-AE7B-FB8170B2C7D1 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:8F25F198-A0F3-4F30-BE42-9AF3A44E890A 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:24C187A9-8D67-4D0E-A171-1885A25B62D7 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:555DF82E-F461-4EBC-82FA-FFDABE3BFFF2 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:7163AA50-6253-46B7-9536-DE7F8D81A14C 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5716DB92-5FF8-4776-ACC5-BF6FA8C2E1BB 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:822872A6-1C40-461F-AA0B-6A20EE06ADBA Abstract. -

Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Chapter 92A)

1 S 23/2005 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 11th January 2005 at 5:00 pm. NO.S 23 ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (CHAPTER 92A) ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (AMENDMENT OF FIRST, SECOND AND THIRD SCHEDULES) NOTIFICATION 2005 In exercise of the powers conferred by section 23 of the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act, the Minister for National Development hereby makes the following Notification: Citation and commencement 1. This Notification may be cited as the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Amendment of First, Second and Third Schedules) Notification 2005 and shall come into operation on 12th January 2005. Deletion and substitution of First, Second and Third Schedules 2. The First, Second and Third Schedules to the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act are deleted and the following Schedules substituted therefor: ‘‘FIRST SCHEDULE S 23/2005 Section 2 (1) SCHEDULED ANIMALS PART I SPECIES LISTED IN APPENDIX I AND II OF CITES In this Schedule, species of an order, family, sub-family or genus means all the species of that order, family, sub-family or genus. First column Second column Third column Common name for information only CHORDATA MAMMALIA MONOTREMATA 2 Tachyglossidae Zaglossus spp. New Guinea Long-nosed Spiny Anteaters DASYUROMORPHIA Dasyuridae Sminthopsis longicaudata Long-tailed Dunnart or Long-tailed Sminthopsis Sminthopsis psammophila Sandhill Dunnart or Sandhill Sminthopsis Thylacinidae Thylacinus cynocephalus Thylacine or Tasmanian Wolf PERAMELEMORPHIA -

A Phylogeny and Revised Classification of Squamata, Including 4161 Species of Lizards and Snakes

BMC Evolutionary Biology This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:93 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-93 Robert Alexander Pyron ([email protected]) Frank T Burbrink ([email protected]) John J Wiens ([email protected]) ISSN 1471-2148 Article type Research article Submission date 30 January 2013 Acceptance date 19 March 2013 Publication date 29 April 2013 Article URL http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/93 Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2013 Pyron et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes Robert Alexander Pyron 1* * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Frank T Burbrink 2,3 Email: [email protected] John J Wiens 4 Email: [email protected] 1 Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St. -

Human-Snake Conflict Patterns in a Dense Urban-Forest Mosaic Landscape

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 14(1):143–154. Submitted: 9 June 2018; Accepted: 25 February 2019; Published: 30 April 2019. HUMAN-SNAKE CONFLICT PATTERNS IN A DENSE URBAN-FOREST MOSAIC LANDSCAPE SAM YUE1,3, TIMOTHY C. BONEBRAKE1, AND LUKE GIBSON2 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, China 2School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China 3Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Human expansion and urbanization have caused an escalation in human-wildlife conflicts worldwide. Of particular concern are human-snake conflicts (HSC), which result in over five million reported cases of snakebite annually and significant medical costs. There is an urgent need to understand HSC to mitigate such incidents, especially in Asia, which holds the highest HSC frequency in the world and the highest projected urbanization rate, though knowledge of HSC patterns is currently lacking. Here, we examined the relationships between season, weather, and habitat type on HSC incidents since 2002 in Hong Kong, China, which contains a mixed landscape of forest, dense urban areas, and habitats across a range of human disturbance and forest succession. HSC frequency peaked in the autumn and spring, likely due to increased activity before and after winter brumation. There were no considerable differences between incidents involving venomous and non-venomous species. Dense urban areas had low HSC, likely due to its inhospitable environment for snakes, while forest cover had no discernible influence on HSC. We found that disturbed or lower quality habitats such as shrubland or areas with minimal vegetation had the highest HSC, likely because such areas contain intermediate densities of snakes and humans, and intermediate levels of disturbance.