Damascus Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pattern Formation in Wootz Damascus Steel Swords and Blades

Indian Journal ofHistory ofScience, 42.4 (2007) 559-574 PATTERN FORMATION IN WOOTZ DAMASCUS STEEL SWORDS AND BLADES JOHN V ERHOEVEN* (Received 14 February 2007) Museum quality wootz Damascus Steel blades are famous for their beautiful surface patterns that are produced in the blades during the forging process of the wootz ingot. At an International meeting on wootz Damascus steel held in New York' in 1985 it was agreed by the experts attending that the art of making these blades had been lost sometime in nineteenth century or before. Shortly after this time the author began a collaborative study with bladesmith Alfred Pendray to tty to discover how to make ingots that could be forged into blades that would match both the surface patterns and the internal carbide banded microstructure of wootz Damascus steels. After carrying out extensive experiments over a period ofaround 10 years this work succeeded to the point where Pendray is now able to consistently make replicas of museum quality wootz Damascus blades that match both surface and internal structures. It was not until near the end of the study that the key factor in the formation of the surface pattern was discovered. It turned out to be the inclusion of vanadium impurities in the steel at amazingly low levels, as low as 0.004% by weight. This paper reviews the development of the collaborative research effort along with our analysis ofhow the low level of vanadium produces the surface patterns. Key words: Damascus steel, Steel, Wootz Damascus steel. INTRODUCTION Indian wootz steel was generally produced by melting a charge of bloomery iron along with various reducing materials in small closed crucibles. -

The White Book of STEEL

The white book of STEEL The white book of steel worldsteel represents approximately 170 steel producers (including 17 of the world’s 20 largest steel companies), national and regional steel industry associations and steel research institutes. worldsteel members represent around 85% of world steel production. worldsteel acts as the focal point for the steel industry, providing global leadership on all major strategic issues affecting the industry, particularly focusing on economic, environmental and social sustainability. worldsteel has taken all possible steps to check and confirm the facts contained in this book – however, some elements will inevitably be open to interpretation. worldsteel does not accept any liability for the accuracy of data, information, opinions or for any printing errors. The white book of steel © World Steel Association 2012 ISBN 978-2-930069-67-8 Design by double-id.com Copywriting by Pyramidion.be This publication is printed on MultiDesign paper. MultiDesign is certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council as environmentally-responsible paper. contEntS Steel before the 18th century 6 Amazing steel 18th to 19th centuries 12 Revolution! 20th century global expansion, 1900-1970s 20 Steel age End of 20th century, start of 21st 32 Going for growth: Innovation of scale Steel industry today & future developments 44 Sustainable steel Glossary 48 Website 50 Please refer to the glossary section on page 48 to find the definition of the words highlighted in blue throughout the book. Detail of India from Ptolemy’s world map. Iron was first found in meteorites (‘gift of the gods’) then thousands of years later was developed into steel, the discovery of which helped shape the ancient (and modern) world 6 Steel bEforE thE 18th cEntury Amazing steel Ever since our ancestors started to mine and smelt iron, they began producing steel. -

Damascus Steel

Damascus steel For Damascus Twist barrels, see Skelp. For the album of blades, and research now shows that carbon nanotubes the same name, see Damascus Steel (album). can be derived from plant fibers,[8] suggesting how the Damascus steel was a type of steel used in Middle East- nanotubes were formed in the steel. Some experts expect to discover such nanotubes in more relics as they are an- alyzed more closely.[6] The origin of the term Damascus steel is somewhat un- certain; it may either refer to swords made or sold in Damascus directly, or it may just refer to the aspect of the typical patterns, by comparison with Damask fabrics (which are in turn named after Damascus).[9][10] 1 History Close-up of an 18th-century Iranian forged Damascus steel sword ern swordmaking. These swords are characterized by dis- tinctive patterns of banding and mottling reminiscent of flowing water. Such blades were reputed to be tough, re- sistant to shattering and capable of being honed to a sharp, resilient edge.[1] Damascus steel was originally made from wootz steel, a steel developed in South India before the Common Era. The original method of producing Damascus steel is not known. Because of differences in raw materials and man- ufacturing techniques, modern attempts to duplicate the metal have not been entirely successful. Despite this, several individuals in modern times have claimed that they have rediscovered the methods by which the original Damascus steel was produced.[2][3] The reputation and history of Damascus steel has given rise to many legends, such as the ability to cut through a rifle barrel or to cut a hair falling across the blade,.[4] A research team in Germany published a report in 2006 re- vealing nanowires and carbon nanotubes in a blade forged A bladesmith from Damascus, ca. -

Does Pattern-Welding Make Anglo-Saxon Swords Stronger?

Does pattern-welding make Anglo-Saxon swords stronger? Thomas Birch Abstract The purpose of pattern-welding, used for the construction of some Anglo-Saxon swords, has yet to be fully resolved. One suggestion is that the technique enhanced the mechanical properties of a blade. Another explanation is that pattern-welding created a desired aesthetic appearance. In order to assess whether the technique affects mechanical properties, this experimental study compared pattern-welded and plain forged blanks in a series of material tests. Specimens were subject to tensile, Charpy and Vickers diamond hardness testing. This was to investigate the relative strength, ductility and toughness of pattern-welding. The results were inconclusive, however the study revealed that the fracture performance of pattern- welding may owe to its use. This paper arises from work conducted in 2006-7 as part of an undergraduate dissertation under the supervision of Dr. Catherine Hills (Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge). Introduction Pattern-welding is the practice of forging strips (sheets and rods) of iron, sometimes of different composition, that have often previously undertaken physical distortions such as twisting and welding (Buchwald 2005, 282; Lang and Ager 1989, 85). It was mainly used in the production of swords and spearheads. The purpose of pattern-welding, however, remains debated. This study sought to understand the purpose of pattern-welding through experimental investigation, with particular reference to why it was used to manufacture some Anglo-Saxon swords. In order to establish whether pattern-welding improved the mechanical properties of a sword, a sample was created and compared to a plain forged control sample. -

An Explanation of Possible Damascus Steel Manufacturing Based On

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MECHANICS An Explanation of Possible Damascus Steel Manufacturing Based on Duration of Transient Nucleate Boiling Process and Prediction of the Future of Controlled Continuous Casting NIKOLAI KOBASKO Intensive Technologies Ltd, Kyiv, Ukraine and IQ Technologies Inc, Akron, USA Abstract - In the paper the new explanation in cementite microstructure were also found in the manufacturing of Damascus steel, based on discovered archeological items from Pol'tse, a settlement at Amur the specific characteristics of transient nucleate boiling river, V-IV century B.C. Raw materials and Damascus processes, is provided. Also, the future of continuous steel crafting instruction are not longer available. Details casting in the paper is discussed. According to of technology, which was used by the capable discovered characteristics, duration of transient nucleate metallurgists from Pol'tse, is not known [8]. The ancient boiling process is directly proportional to squared size of technique reached modern - day Turkmenistan and a steel part and inversely proportional to thermal Uzbekistan around 900 A.D., and then the Middle East diffusivity of material, depends on configuration and circa 1000 A.D. There are numerous publications where initial temperature of component, thermal properties of this matter is widely discussed [9 - 16]. It is underlined liquid. The surface temperature of steel part during that India has been reputed for its iron and steel since transient nucleate boiling process maintains at the level ancient times, the time of Alexander the Great (356 B.C. of boiling point of liquid and cannot be below it. Based - 323 B.C.) [5] . When Alexander the Great got to India on these characteristics, the new hypothesis regarding he ordered to be delivered to him “100 talents of Indian manufacturing of Damascus steel is proposed according steel” [5]. -

Formation of Faceted Excess Carbides in Damascus Steels Ledeburite Class

Journal of Materials Science and Engineering B 8 (1-2) (2018) 36-44 doi: 10.17265/2161-6221/2018.1-2.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Formation of Faceted Excess Carbides in Damascus Steels Ledeburite Class Dmitry Sukhanov1 and Natalia Plotnikova2 1. ASK-MSC Company (Metallurgy), Moscow 117246, Russia 2. Novosibirsk State Technical University, Novosibirsk 630073, Russia Abstract: In this research was developed stages of formation troostite-carbide structure into pure Damascus steel ledeburite class type BU22А obtained by vacuum melting. In the first stage of the technological process, continuous carbides sheath was formed along the boundaries of austenitic grains, which morphologically resembles the inclusion of ledeburite. In the second stage of the process, there is a seal and faceted large carbide formations of eutectic type. In the third stage of the technological process, troostite matrix is formed with a faceted eutectic carbide non-uniformly distributed in the direction of the deformation with size from 5.0 μm to 20 μm. It found that the stoichiometric composition of faceted eutectic carbides is in the range of 34 < C < 36 (atom %), which corresponds to -carbide type Fe2C with hexagonal close-packed lattice. Considering stages of transformation of metastable ledeburite in the faceted eutectic -carbides type Fe2C, it revealed that the duration of isothermal exposure during heating to the eutectic temperature, is an integral part of the process of formation of new excess carbides type Fe2C with a hexagonal close-packed lattice. It is shown that troostite-carbide structure Damascus steel ledeburite class (BU22А), with volume fraction of excess -carbide more than 20%, is fully consistent with the highest grades of Indian steels type Wootz. -

The State of The

swords.qxd 7/14/04 9:33 PM Page 1 SWORDSMITHING In ancient times, the sword represented the THE STATE pinnacle of the OF THE engineering craft. Today, many of the same ART technologies are used to produce swords for a variety of purposes. Byron J. Skillings* Ladish Co., Inc. Cudahy, Wisconsin ince early times, the search for superior arms and armor has driven the art and the science of metallurgy. European, Middle- Eastern, and Eastern cultures each devel- Fig. 2 — The rapier was not considered a Soped metallurgical and bladesmithing technolo- military weapon, but rather served as a per- gies suitable for their swords, for personal defense sonal side arm for self-defense and for settling and military weapons. Swords were symbols as duels. This rapier is by Kevin Cashen, Math- erton Forge. well as weapons, used to show positions in gov- ernment, social status, and wealth. The sword, ar- guably more than any other of man’s tools, speaks of our innate drive to create items of form as well as function. They were for many eons the pinnacle of the engineering craft. Without scientific knowl- edge and analytical equipment, ancient smiths were able to convert impure contaminated raw ore into refined metal. From this material they consistently produced the lightest, strongest, most resilient tools Fig. 3 — Medieval sword by Randal suited for a purpose where failure meant death. Graham has a simpler hilt than the This was an incredible achievement. rapier. This is an example of an in- terpretation of a historical sword, not a duplication. Image courtesy Early swords Albion Armorers. -

The Serpent in the Sword: Pattern-Welding in Early Medieval Swords

The Serpent in the Sword: Pattern-welding in Early Medieval Swords by LEE A. JONES From the time of its first appearance about 4,000 years ago, the sword soon became the pre-eminent weapon of personal defense and has been a preferred vehicle for technological and artistic expression even since its relatively recent decline. Within what at first seems to be merely a simple variation of that basic tool, the inclined plane, metallurgical studies have revealed complex piled structures in iron swords dating from as early as Celtic times13 (500 BC). Being composed of several rods welded together and running the length of the blade, such piled structures allowed the smith st to localize desired properties by empirically joining 1. Detail of the blade of a Celtic sword from the 1 cen- tury BC, in an area presumably bent prior to inhumation together irons with differing properties owing to dif- and later straightened. Differential corrosion discloses ferent origins and concentrations of trace elements. separate elements for the cutting edges and vague linear- Additionally, small rods could be carburized to increase ity parallel to the long axis suggests piled construction. A hardness by increasing carbon content. Ideally, steel parallel stress fracture is seen to the left and may be along (which is an alloy of iron with small amounts of car- a welded boundary (Private collection). bon) would be chosen to provide hardness at the edge. However, since an increased carbon content concomi- presentation grade sabers and daggers, including those tantly causes brittleness, softer and more malleable of the Third Reich14. -

Damascus Steel Part 3 4 Lanham Scrimshaw 4 WG Nessmuk 4 Unfinished Projects 4 No Meetings for Awhile

KNEWSLETTTER IN A KNUTSHELL 4 Damascus Steel Part 3 4 Lanham Scrimshaw 4 WG Nessmuk 4 Unfinished Projects 4 No meetings for awhile Our international membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” April 2021 Damascus Steel Part 3 Gene Martin So far we’ve talked about the origins and basics of making Damascus, or pattern welded, steel. Since there is a reason for it being called pattern welded steel, this missive will discuss Image 1580 - A low layer billet with reverse twist. Three pieces actually putting patterns in the steel. While the article about will be stacked to form the full billet. making Damascus was very broad and general, now we’re going to get much more specific. As we discussed before, a billet of pattern welded steel starts life as a stack of steel pieces of alternating types of steel. Forge welding that stack into a billet produces basic random pattern Image 1583 - A fold too far. The pattern is so fine it’s hard to see. Damascus. While random pattern can be really attractive, it is seldom exciting. Manipulating that pattern starts down the road towards exciting. Some of the basic patterns are ladder and twist pattern. Let’s discuss how those patterns are created. Ladder pattern is created by creating vertical grooves, hopefully evenly spaced, down the length of the billet. Those grooves can be created with a file, a grinder, or dies in a press or power hammer. More Image 1590 – A four bar composite pattern. Bought this from Tru-Grit from an estate. -

Jeff Wadsworth: Probed How Damascus Steel Swords Made (As Published in the Oak Ridger’S Historically Speaking Column on May 12, 2014)

Jeff Wadsworth: Probed how Damascus steel swords made (As published in The Oak Ridger’s Historically Speaking column on May 12, 2014) As Carolyn Krause continues to bring us superb insights into some of the key leaders of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, she has delved into the past to bring forward some astounding facts about Jeff Wadsworth, the metallurgist. He, being intrigued by the past art of sword making, learned the secret of the steel used in a most effective hand to hand combat weapon, the Damascus sword. … Al Trivelpiece pedals his unicycle without losing his balance. Bill Madia drives his motorcycle on Bethel Valley Road. In a demonstration Jeff Wadsworth splits a silk scarf midair using an ancient Damascus steel sword. These are my occasional visions of the past three directors of Oak Ridge National Laboratory. In September 1981 Wadsworth’s metallurgical research at Stanford University was beginning to pay off. He and Oleg Sherby, a professor at Stanford and an authority on deformable metals, published a notable paper in the British scientific journal “Progress in Materials Science.” Even better, renowned science writer Walter Sullivan highlighted their research in his article “The Mystery of Damascus Steel Appears Solved” in the Sept. 29, 1981, issue of The New York Times. At one of the metallurgists’ presentations on their high-carbon steel, a sword enthusiast noted that Damascus steel was also rich in carbon. So, Sherby and Wadsworth decided to compare the composition of their own steel with that of ancient Damascus steel used for swords, shields and armor and prized for their wavy, watery “damask” patterns. -

Revealing the Surface Pattern of Medieval Pattern Welded Iron Objects – Etching Tests Conducted on Reconstructed Composites

ARCHEOLOGIA TECHNICA / 25 / 2014 / 18–24 18 REVEALING THE SURFACE PATTERN OF MEDIEVAL PATTERN WELDED IRON OBJECTS – ETCHING TESTS CONDUCTED ON RECONSTRUCTED COMPOSITES Adam Thiele, Jiří Hošek, Márk Hazamza, Béla Török Pattern welding is a forging technique used for making and employing laminate composites that reveal a surface pattern after polishing and etching. The technique was widely used within the period of the late 2nd to the 14th century AD in the manufacture of ostentatious swords, scramasaxes, knives and spear-heads. Although pattern welding derived from piling wrought iron and steel together, deliberately created surface patterns were, since the 2nd century at the latest, revealed by composites employing phosphoric iron as the basic constituent. As the readability of the patterned surfaces is significantly enhanced by etching, one can assume that historical pattern welded objects were somehow etched. Hence, the basic question arises: which material combination and what etching parameters lead to the most contrasting and visible pattern? Another important question is: how can archaeometallurgists and conservator-restorers reveal surviving pattern welded elements of archaeologically excavated iron objects without a risk of misinterpretation and destabilization of the objects studied? In an attempt to answer these questions, samples detached from patterned welded rods combining phosphoric iron, wrought iron and steel were ground and etched using six different acids (which could be available in the 2nd–14th centuries) under various conditions concerning acid concentration, temperature and etching time. The etching test revealed that the most visible pattern appears in the case of composites combining phosphoric iron and tempered steel, when hydrochloric acid is applied as etchant. -

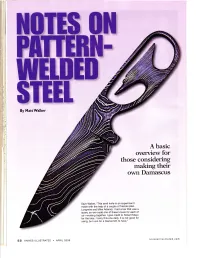

A Basic Ovendew for Those Considering Making Their Own Damascus

By MattWalker A basic ovendew for those considering making their own Damascus SaysWalker, "This anvil knife is an experimentI made with the help of a couple of friends(Alan Longmireand Mike Adams).I had a bar that was a spare,so we made one of these knivesfor each of us-working together.I give creditto RobertMayo for the idea.I carrythis one daily.lt is not good for using,but cool for a blacksmithto have." knivesillustrated.com 52 KNIVES ILLUSTRATED . APRIL 2009 want to give an overviewof how I makeDamascus steel, along with someopinions and ideas about it. This is what works in my shopfor me. Making Damascusis almosta faith- basedpursuit for me. If you talk with severalpeople that areserious about Damascusyou will seewhy I sayit is somewhatlike religion-we areall trying to get to the sameplace, but often value differentformalities in the practiceof gettingthere. My advicefor anyonewanting to start makingDamascus is to learneverything you canand use what works for you.No- body is born knowing this stuff.At the end of this articleI will credit someof the peopleI havelearned from and mentionresources I value. Materials Matt Walkerin his shop Most steelsand even wrought iron, can be weldedand manipulated to createpat- I usenickel in my barsonly whenmy My personalrecommendation is 1084 terns.If you put wroughtiron, mild steel informedcustomers ask for it. Nickel re- and 15N20.This combinationprovides or nickelin theoriginal billet, you run the ally doesmake a piecepretty and, in my everythingI want for a piecethat I can risk of havinglayers that won't hardenor business,whoever is payingcan choose provideto otherswith confidence.The the lowercarbon layers robbing from the what materialthey want.