A Holocaust Survival Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust Education Teacher Resources Why Teach The

Holocaust Education Teacher Resources Compiled by Sasha Wittes, Holocaust Education Facilitator For Ilana Krygier Lapides, Director, Holocaust & Human Rights Education Calgary Jewish Federation Why Teach The Holocaust? The Holocaust illustrates how silence and indifference to the suffering of others, can unintentionally, serve to perpetuate the problem. It is an unparalleled event in history that brings to the forefront the horrors of racism, prejudice, and anti-Semitism, as well as the capacity for human evil. The Canadian education system should aim to be: democratic, non-repressive, humanistic and non-discriminating. It should promote tolerance and offer bridges for understanding of the other for reducing alienation and for accommodating differences. Democratic education is the backbone of a democratic society, one that fosters the underpinning values of respect, morality, and citizenship. Through understanding of the events, education surrounding the Holocaust has the ability to broaden students understanding of stereotyping and scapegoating, ensuring they become aware of some of the political, social, and economic antecedents of racism and provide a potent illustration of both the bystander effect, and the dangers posed by an unthinking conformity to social norms and group peer pressure. The study of the Holocaust coupled with Canada’s struggle with its own problems and challenges related to anti-Semitism, racism, and xenophobia will shed light on the issues facing our society. What was The Holocaust? History’s most extreme example of anti- Semitism, the Holocaust, was the systematic state sponsored, bureaucratic, persecution and annihilation of European Jewry by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1933-1945. The term “Holocaust” is originally of Greek origin, meaning ‘sacrifice by fire’ (www.ushmm.org). -

Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Sociology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2012 Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds Recommended Citation Halbgewachs, Nancy Copeland. "Censorship and Holocaust Film in the Hollywood Studio System." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/soc_etds/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nancy Copeland Halbgewachs Candidate Department of Sociology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. George A. Huaco , Chairperson Dr. Richard Couglin Dr. Susan Tiano Dr. James D. Stone i CENSORSHIP AND HOLOCAUST FILM IN THE HOLLYWOOD STUDIO SYSTEM BY NANCY COPELAND HALBGEWACHS B.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1962 M.A., Sociology, University of Kansas, 1966 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2011 ii DEDICATION In memory of My uncle, Leonard Preston Fox who served with General Dwight D. Eisenhower during World War II and his wife, my Aunt Bonnie, who visited us while he was overseas. My friend, Dorothy L. Miller who as a Red Cross worker was responsible for one of the camps that served those released from one of the death camps at the end of the war. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

Hoose Civility

hoose civility T11(; Modesto Citv Sdhlols Board ot Education tlw countY-\,\'ide "Choose Civility" initiativE' and to encourage and model (ivil behavior. MODESTO CITY SCHOOLS BOARD OF EDUCATION AGENDA BOARD ROOM IN THE STAFF DEVELOPMENT CENTER 1326th REGULAR MEETING July 9, 2012 Period for Public Presentations 6:15 p.m.* In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, if you need special assistance to participate in this meeting, please contact the Superintendent's office, 576-4141. Notification 48 hours prior to the meeting will enable the District to make reasonable arrangements to ensure accessibility to this meeting. Any writings or documents that are public records and are provided to a majority of the governing board regarding an open session item on this agenda will be made available for public inspection in the District office located at 426 Locust Street during normal business hours. * Times are approximate. Individuals wishing to address an agenda item should plan accordingly. A. INITIAL MATTERS: 5:00 to 5:01 1. Call to Order. 5:01 to 6:00 2. Closed Session. Public comment regarding closed session items will be received before the Board goes into closed session. 1 Conference with Legal Counsel: Pending Litigation; No. Cases: One Stanislaus Superior Court Case No. CV 647498 . .2 Public Employee Appointments: >- Appointment of Directors, Educational Services >- Appointment of Director, Parent and Community Involvement >- Appointment of Principal, 9-12 .3 Conference with District Labor Negotiator: Craig Rydquist regarding employee organizations: Modesto Teachers' Association and California School Employees Association, Chapter No. 007; and Unrepresented Employees (Managers and Administrators) . Regular Meeting July 9, 2012 A. -

The Survivor's Hunt for Nazi Fugitives in Brazil: The

THE SURVIVOR’S HUNT FOR NAZI FUGITIVES IN BRAZIL: THE CASES OF FRANZ STANGL AND GUSTAV WAGNER IN THE CONTEXT OF INTERNATIONAL JUSTICE by Kyle Leland McLain A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Charlotte 2016 Approved by: ______________________________ Dr. Heather Perry ______________________________ Dr. Jürgen Buchenau ______________________________ Dr. John Cox ii ©2016 Kyle Leland McLain ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT KYLE LELAND MCLAIN. The survivor’s hunt for Nazi fugitives in Brazil: the cases of Franz Stangl and Gustav Wagner in the context of international justice (Under the direction of DR. HEATHER PERRY) On April 23, 1978, Brazilian authorities arrested Gustav Wagner, a former Nazi internationally wanted for his crimes committed during the Holocaust. Despite a confirming witness and petitions from West Germany, Israel, Poland and Austria, the Brazilian Supreme Court blocked Wagner’s extradition and released him in 1979. Earlier in 1967, Brazil extradited Wagner’s former commanding officer, Franz Stangl, who stood trial in West Germany, was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. These two particular cases present a paradox in the international hunt to bring Nazi war criminals to justice. They both had almost identical experiences during the war and their escape, yet opposite outcomes once arrested. Trials against war criminals, particularly in West Germany, yielded some successes, but many resulted in acquittals or light sentences. Some Jewish survivors sought extrajudicial means to see that Holocaust perpetrators received their due justice. Some resorted to violence, such as vigilante justice carried out by “Jewish vengeance squads.” In other cases, private survivor and Jewish organizations collaborated to acquire information, lobby diplomatic representatives and draw public attention to the fact that many Nazi war criminals were still at large. -

Everyday Objects from the Holocaust-PT 2

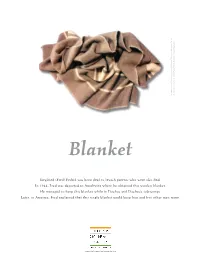

On display at the Washington State Holocaust Education Resource Center. State Holocaust Education Resource Center. Washington On display at the Harve Photo by of Siegfried Fedrid. On loan from the family Bergmann. Blanket Siegfried (Fred) Fedrid was born deaf to Jewish parents who were also deaf. In 1944, Fred was deported to Auschwitz where he obtained this woolen blanket. He managed to keep this blanket while in Dachau and Dachau’s sub-camps. Later, in America, Fred explained that this single blanket could keep him and five other men warm. www.HolocaustCenterSeattle.org A seven year-old Siegfried “Fred” Fedrid pictured with his mother, an aunt, and other cousins in Vienna, circa 1927. Fred was the only survivor. iegfried “Fred” Fedrid was born in April 1920 When Fred returned to Vienna to look for his friends in Vienna, Austria. Fred was born deaf to and relatives, he found no one. Further, he was told Jewish parents who were also deaf. In 1936 Fred that the Nazis had sold all of the possessions he and his Sgraduated from the School for the Deaf in Vienna. At parents had left behind. He had lost everything. 16 years old, he began an apprenticeship in a custom tailor shop. He trained there until 1938, when the Fred was hired at a Nazis forced the owner of the shop, a Jewish man, to “He wanted people to custom tailor shop, close his business. know that deaf people lived in a rented room, are capable, intelligent, and supported himself. In October of 1941, the Gestapo arrested Fred and his and able to support family. -

De Verbeelding Van Concentratiekampen in Speelfilms

De verbeelding van concentratiekampen in speelfilms Een onderzoek naar de representatie van concentratiekampen in speelfilms Masterscriptie Daniël de Jong S4493567 Faculteit der Letteren Master Geschiedenis & Actualiteit Begeleider: Dr. R. Ensel Datum: 15 augustus 2019 Radboud Universiteit Inhoud Hoofdstuk 1: Inleiding .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Onderwerp ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Status Quaestionis ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.2.A. De Holocaust ....................................................................................................................... 4 1.2.B. Concentratiekampen .......................................................................................................... 5 1.2.C. De visuele verbeeldingen van concentratiekampen ......................................................... 9 1.3 Bronnen, hypothese en methoden ............................................................................................ 13 1.3.A. Bronnen ............................................................................................................................. 13 1.3.B. Hypothese .......................................................................................................................... 15 1.3.C. Methoden -

Pre-0Wned DVD's and Blu-Rays Listed on Dougsmovies.Com 2 Family

Pre-0wned DVD’s and Blu-rays Listed on DougsMovies.com Quality: All movies are in excellent condition unless otherwise noted Price: Most single DVD’s are $3.00. Boxed Sets, Multi-packs and hard to find movies are priced accordingly. Volume Discounts: 12-24 items 10% off / 25-49 items 20% off / 50-99 items 30% off / 100 or more items 35% off Payment: We accept PayPal for online orders. We accept cash only for local pick up orders. Shipping: USPS Media Mail. $3.25 for the first item. Add $0.20 for each additional item. Free pick up in Amelia, OH also available. Orders will ship within 24-48 hours of payment. USPS tracking numbers will be provided. Inventory as of 03/18/2021 TITLE Inventory as of 03/18/2021 Format Price 2 Family Time Movies - Seven Alone / The Missouri Traveler DVD 5.00 3 Docudramas (religious themed) Breaking the DaVinci Code / The Miraculous Mission / The Search for Heaven DVD 6.00 4 Sci-Fi Film Collector’s Set The Sender / The Code Conspiracy / The Invader / Storm Trooper DVD 7.50 4 Family Adventure Film Set Spirit Bear / Sign of the Otter / Spirit of the Eagle / White Fang (Still Sealed) DVD 7.50 8 Mile DVD 3.00 12 Rounds DVD 3.00 20 Leading Men – 24 disc set - 0 full length movies featuring actors from the Golden Age of films – Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, James Stewart, etc DVD 10.00 20 Classic Musicals: Legends of Stage and Screeen 4-Disc Boxed Set DVD 10.00 50 Classic Musicals - 12 Disc Boxed Set in Plastic Case – Over 66 hours Boxed Set DVD 15.00 50 First Dates DVD 3.00 50 Hollywood Legends - 50 Movie Pack - 12 Disc -

Stanislaw Smajzner Extracts from the Tragedy of a Jewish Teenager

Stanislaw Smajzner Extracts from the Tragedy of a Jewish Teenager Stanislaw Smajzner After His Escape From Sobibor 1. Opole Ghetto Precisely on the 10th May 1942 with spring in full bloom, the last fearful summons came. All the hundreds of refugees who had escaped up to that moment, would have to go to the notorious place and at the same hour as before. They warned us very seriously that no-one should try to oppose them or try to hide, since those who did so would be immediately shot down. They added that , as of that day , our community would be extinguished, and for that reason it would be useless for us to stay. They gave us some other orders and threats and at eleven o’clock next day, the ill fated square was filled by those Jews who had been left behind, each one with his bundle at hand. Among them were my parents, my brother my sister, my nephew and myself. In our group was also one of my cousins from Wolwonice, Nojech Szmajner. It was then we learned about our destination, although we did not know why we were being sent. Rows and columns were made and we left the ghetto of Opole for the last time. Outside the gate we saw a large number of carts, since we already been counted, we left and in a few minutes we were far from the town, crossing fields covered with multi-coloured flowers and leaving Opole Lubelskie behind. We were now facing something imponderable. I later learned that only the members of the Judenrat and of the Jewish police , as well as the privileged elements who orbited around that organisation , were not part of this transport. -

Barbara Małyszczak Zbrojne Powstanie Więźniów I Likwidacja Obozu Zagłady W Sobiborze

Barbara Małyszczak Zbrojne powstanie więźniów i likwidacja obozu zagłady w Sobiborze Rocznik Lubelski 39, 169-181 2013 Barbara Małyszczak Lublin Zbrojne powstanie więźniów i likwidacja obozu zagłady w Sobiborze Uwagi wstępne W ramach Akcji Reinhardt1 w pobliżu maleńkiej wsi Sobibór2 położonej nie- opodal miasta Włodawa powstał jeden z obozów masowej zagłady. Tę małą miej- scowość wskazał jako teren pod budowę obozu śmierci SS-Obergruppenführer Odilo Globocnik3. Obóz funkcjonował od 1942 do 1943 r., kiedy doszło do zbroj- nego buntu więźniów i ich ucieczki. Na przestrzeni kilkunastu miesięcy4 wymor- dowano w Sobiborze setki tysięcy Żydów i zmuszano do katorżniczej pracy setki więźniów wybranych spośród przybyłych transportów5. Więźniowie sobiborskiego obozu zagłady codziennie walczyli o przetrwa- nie, zastanawiając się nad ucieczką z miejsca kaźni. Dla jednych formą ratunku była egzekucja, inni opierali się nazistom poprzez kontrabandę i wzajemną po- moc. Oprawcy zdawali sobie sprawę z tego, że więźniowie mogą próbować uciec 1 „Akcja Reinhardt” to kryptonim planu ostatecznego rozwiązania kwestii żydowskiej (z niem. Endlösung der Judenfrage). Operacja wzięła nazwę od nazwiska sekretarza stanu w Ministerstwie Finansów III Rzeszy – Frit- za Reinhardta. Była punktem kulminacyjnym prowadzonej przez nazistów polityki wobec Żydów. Kryptonim ten po raz pierwszy pojawił się na początku czerwca 1942 r. i określał akcję mającą na celu eksterminację Żydów europejskich, a także grabież ich mienia. Na obszarze Generalnej Guberni zlokalizowane zostały miejsca zagła- dy ludności żydowskiej – dwa obozy zostały ulokowane na terenie dystryktu lubelskiego w okolicach wsi Sobi- bór i Bełżec, trzeci zaś nieopodal Warszawy, w okolicach wsi Treblinka. Siedzibę Akcji Reinhardt zlokalizowano w Lublinie, gdzie mieściła się również kwatera Odila Globocnika (dzisiejszy budynek Collegium Iuridicum KUL przy ul. -

Everyday Objects from the Holocaust PART

EverydayEveryday Objects:Objects: ArtifactsArtifactsEveryday from from WashingtonWashington Objects: State State ArtifactsHolocaustHolocaust from Washington SurvivorsSurvivors State Holocaust Survivors LearningLearning about about the HolocaustHolocaust UsingUsingUsing primary Primary Primary sources SourcesSources to learn about the Holocaust 206-441-5747206-441-5747 • www.wsherc.orgwww.wsherc.org This project isThis made project possible is madein part possible by a grant in part from by Humanities a grant from Washington, Humanities aWashington, state-wide non-profita state-wide organization non-profit supported by organizationthe supported National by Endowment the National for Endowment the Humanities for the and Humanities local contributors. and local contributors. www.HolocaustCenterSeattle.org FundingFunding also provided byby thethe Women’sWomen’s Endowment Endowment Foundation, Foundation, aa supporting supporting foundationfoundation of the Jewish Federation of GreaterGreater Seattle. This project is made possible in part by a grant from Humanities Washington, a state-wide non-profit organization supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and local contributors. Funding is also provided by the Women’s Endowment Foundation, a supporting foundation of the Jewish Federation of Greater Seattle. Autograph Book “This book belongs to Hester Waas.” January 25, 1939 - Hester was 12 years old when she received this journal. Hester had her family members and friends sign the book with messages and drawings. Hester’s 15 year old brother Isaac wrote: 6 February 1939. There is in the world one pleasure for everybody whether happy or sad...Her name? Mother Nature! Hester’s brother and parents were deported to Auschwitz in 1942 and did not survive the Holocaust. www.HolocaustCenterSeattle.org ester “The van Westerings had three children and my duties Waas involved taking care of them and cleaning the house. -

Film at the 2017 Academy Awards.) in April, 1940, German Land, Sea, and Air Forces, Sent Supposedly to “Protect Danish Neutrality,” Overran Denmark in Less Than a Day

LAND OF MINE A review by Jonathan Lighter WHICHEVER INDUSTRY BRAIN TURNED the Danish title Under sandet (“under the sand”) into Land of Mine (2015) should probably be demoted to snack-cart management—even though the movie does feature plenty of live, buried land mines. (If punning is in order, “In the Presence of Mine Enemies” might have served as well.) But fortunately, Land of Mine, addressing an obscure episode of 1945-46, is provocative, gripping, and even edifying as it quarries new ground. Those who don’t cringe a little at its well-meaning contrivances should find it sad and moving as well. (It was nominated as Best Foreign Language Film at the 2017 Academy Awards.) In April, 1940, German land, sea, and air forces, sent supposedly to “protect Danish neutrality,” overran Denmark in less than a day. Allowed to retain their national government and treated as “fellow Aryans,” the population remained mostly acquiescent for half the war. But in 1943, when the Germans took absolute control and Hitler targeted the nation’s Jews, members of the Danish resistance ferried more than 90% of the country’s nearly 8,000 Jews to safety in neutral Sweden almost overnight. And of more than four hundred Danish Jews who did fall into the hands of the Nazis, most—astonishingly—were released through Danish governmental negotiations with Heinrich Himmler. The rescue of the Jews earned Denmark a reputation for unusual gallantry and humanity under the Nazi regime. But, in his third feature film, Danish writer-director Martin Zandvliet questions the assumption that his country had a special edge on virtue in the 1940s, as he takes on a morally ambiguous policy exercised after V-E Day by the Danish government (among others).