1. at Some Point During the Late Spring of 1983, Richard Baker Realized He Was in a Pickle. He Wasn't Alone. Hundreds of P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Description Job Number Date Thompson Lawn 1350 1946 August Peter Thatcher 1467 undated Villa Moderne, Taylor and Vial - Carmel 1645-1951 1948 Telephone Building 1843 1949 Abrego House 1866 undated Abrasive Tools - Bob Gilmore 2014, 2015 1950 Inn at Del Monte, J.C. Warnecke. Mark Thomas 2579 1955 Adachi Florists 2834 1957 Becks - interiors 2874 1961 Nicholas Ten Broek 2878 1961 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1517 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1581 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1873 circa 1945-1960 Portraits unnumbered circa 1945-1960 [Naval Radio Training School, Monterey] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 [Men in Hardhats - Sign reads, "Hitler Asked for It! Free Labor is Building the Reply"] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 CZ [Crown Zellerbach] Building - Sonoma 81510 1959 May C.Z. - SOM 81552 1959 September C.Z. - SOM 81561 1959 September Crown Zellerbach Bldg. 81680 1960 California and Chicago: landscapes and urban scenes unnumbered circa 1945-1960 Spain 85343 1957-1958 Fleurville, France 85344 1957 Berardi fountain & water clock, Rome 85347 1980 Conciliazione fountain, Rome 84154 1980 Ferraioli fountain, Rome 84158 1980 La Galea fountain, in Vatican, Rome 84160 1980 Leone de Vaticano fountain (RR station), Rome 84163 1980 Mascherone in Vaticano fountain, Rome 84167 1980 Pantheon fountain, Rome 84179 1980 1 UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Quatre Fountain, Rome 84186 1980 Torlonai -

Monterey County

Steelhead/rainbow trout resources of Monterey County Salinas River The Salinas River consists of more than 75 stream miles and drains a watershed of about 4,780 square miles. The river flows northwest from headwaters on the north side of Garcia Mountain to its mouth near the town of Marina. A stone and concrete dam is located about 8.5 miles downstream from the Salinas Dam. It is approximately 14 feet high and is considered a total passage barrier (Hill pers. comm.). The dam forming Santa Margarita Lake is located at stream mile 154 and was constructed in 1941. The Salinas Dam is operated under an agreement requiring that a “live stream” be maintained in the Salinas River from the dam continuously to the confluence of the Salinas and Nacimiento rivers. When a “live stream” cannot be maintained, operators are to release the amount of the reservoir inflow. At times, there is insufficient inflow to ensure a “live stream” to the Nacimiento River (Biskner and Gallagher 1995). In addition, two of the three largest tributaries of the Salinas River have large water storage projects. Releases are made from both the San Antonio and Nacimiento reservoirs that contribute to flows in the Salinas River. Operations are described in an appendix to a 2001 EIR: “ During periods when…natural flow in the Salinas River reaches the north end of the valley, releases are cut back to minimum levels to maximize storage. Minimum releases of 25 cfs are required by agreement with CDFG and flows generally range from 25-25[sic] cfs during the minimum release phase of operations. -

Santiago Fire

Basin-Indians Fire Basin Complex CA-LPF-001691 Indians Fire CA-LPF-001491 State Emergency Assessment Team (SEAT) Report DRAFT Affecting Watersheds in Monterey County California Table of Contents Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………… Team Members ………………………………………………………………………… Contacts ………………………………………………………..…………………….… Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. Summary of Technical Reports ……………………………………..………………. Draft Technical Reports ……………………………………………………..…………..…… Geology ……………………………………………………………………...……….… Hydrology ………………………………………………………………………………. Soils …………………………………………………………………………………….. Wildlife ………………………………………………………………….………………. Botany …………………………………………………………………………………... Marine Resources/Fisheries ………………………………………………………….. Cultural Resources ………………………………………………………..…………… List of Appendices ……………………………………………………………………………… Hazard Location Summary Sheet ……………………………………………………. Burn Soil Severity Map ………………………………………………………………… Land Ownership Map ……………………………………………………..…………... Contact List …………………………………………………………………………….. Risk to Lives and Property Maps ……………………………………….…………….. STATE EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT TEAM (SEAT) REPORT The scope of the assessment and the information contained in this report should not be construed to be either comprehensive or conclusive, or to address all possible impacts that might be ascribed to the fire effect. Post fire effects in each area are unique and subject to a variety of physical and climatic factors which cannot be accurately predicted. The information in this report was developed from cursory field -

1 Collections

A. andersonii A. Gray SANTA CRUZ MANZANITA San Mateo Along Skyline Blvd. between Gulch Road and la Honda Rd. (A. regismontana?) Santa Cruz Along Empire Grade, about 2 miles north of its intersection with Alba Grade. Lat. N. 37° 07', Long. 122° 10' W. Altitude about 2550 feet. Santa Cruz Aong grade (summit) 0.8 mi nw Alba Road junction (2600 ft elev. above and nw of Ben Lomond (town)) - Empire Grade Santa Cruz Near Summit of Opal Creek Rd., Big Basin Redwood State Park. Santa Cruz Near intersection of Empire Grade and Alba Grade. ben Lomond Mountain. Santa Cruz Along China Grade, 0.2 miles NW of its intersection with the Big Basin-Saratoga Summit Rd. Santa Cruz Nisene Marks State Park, Aptos Creek watershed; under PG&E high-voltage transmission line on eastern rim of the creek canyon Santa Cruz Along Redwood Drive 1.5 miles up (north of) from Monte Toyon Santa Cruz Miller's Ranch, summit between Gilroy and Watsonville. Santa Cruz At junction of Alba Road and Empire Road Ben Lomond Ridge summit Santa Cruz Sandy ridges near Bonny Doon - Santa Cruz Mountains Santa Cruz 3 miles NW of Santa Cruz, on upper UC Santa Cruz campus, Marshall Fields Santa Cruz Mt. Madonna Road along summit of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Between Lands End and Manzanitas School. Lat. N. 37° 02', Long. 121° 45' W; elev. 2000 feet Monterey Moro Road, Prunedale (A. pajaroensis?) A. auriculata Eastw. MT. DIABLO MANZANITA Contra Costa Between two major cuts of Cowell Cement Company (w face of ridge) - Mount Diablo, Lime Ridge Contra Costa Immediately south of Nortonville; 37°57'N, 121°53'W Contra Costa Top Pine Canyon Ridge (s-facing slope between the two forks) - Mount Diablo, Emmons Canyon (off Stone Valley) Contra Costa Near fire trail which runs s from large spur (on meridian) heading into Sycamore Canyon - Mount Diablo, Inner Black Hills Contra Costa Off Summit Dr. -

Abies Bracteata Revised 2011 1 Abies Bracteata (D. Don) Poit

Lead Forest: Los Padres National Forest Forest Service Endemic: No Abies bracteata (D. Don) Poit. (bristlecone fir) Known Potential Synonym: Abies venusta (Douglas ex Hook.) K. Koch; Pinus bracteata D. Don; Pinus venusta Douglas ex Hook (Tropicos 2011). Table 1. Legal or Protection Status (CNDDB 2011, CNPS 2011, and Other Sources). Federal Listing Status; State Heritage Rank California Rare Other Lists Listing Status Plant Rank None; None G2/S2.3 1B.3 USFS Sensitive Plant description: Abies bracteata (Pinaceae) (Fig. 1) is a perennial monoecious plant with trunks longer than 55 m and less than 1.3 m wide. The branches are more-or-less drooping, and the bark is thin. The twigs are glabrous, and the buds are 1-2.5 cm long, sharp-pointed, and non- resinous. The leaves are less than 6 cm long, are dark green, faintly grooved on their upper surfaces, and have tips that are sharply spiny. Seed cones are less than 9 cm long with stalks that are under15 mm long. The cones have bracts that are spreading, exserted, and that are 1.5–4.5 cm long with a slender spine at the apex. Taxonomy: Abies bracteata is a fir species and a member of the pine family (Pinaceae). Out of the fir species growing in North America (Griffin and Critchfield 1976), Abies bracteata has the smallest range and is the least abundant. Identification: Many features of A. bracteata can be used to distinguish this species from other conifers, including the sharp-tipped needles, thin bark, club-shaped crown, non-resinous buds, and exserted spine tipped bracts (Gymnosperms Database 2010). -

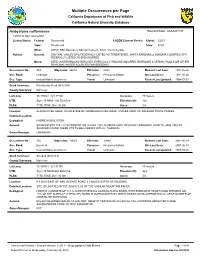

Multiple Occurrences Per Page California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Natural Diversity Database

Multiple Occurrences per Page California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Natural Diversity Database Ambystoma californiense Element Code: AAAAA01180 California tiger salamander Listing Status: Federal: Threatened CNDDB Element Ranks: Global: G2G3 State: Threatened State: S2S3 Other: CDFW_SSC-Species of Special Concern, IUCN_VU-Vulnerable Habitat: General: CENTRAL VALLEY DPS FEDERALLY LISTED AS THREATENED. SANTA BARBARA & SONOMA COUNTIES DPS FEDERALLY LISTED AS ENDANGERED. Micro: NEED UNDERGROUND REFUGES, ESPECIALLY GROUND SQUIRREL BURROWS & VERNAL POOLS OR OTHER SEASONAL WATER SOURCES FOR BREEDING Occurrence No. 249 Map Index: 26014 EO Index: 5033 Element Last Seen: 1991-05-26 Occ. Rank: Unknown Presence: Presumed Extant Site Last Seen: 1991-05-26 Occ. Type: Natural/Native occurrence Trend: Unknown Record Last Updated: 2004-07-01 Quad Summary: Palo Escrito Peak (3612144) County Summary: Monterey Lat/Long: 36.47562 / -121.47102 Accuracy: 80 meters UTM: Zone-10 N4037790 E636975 Elevation (ft): 120 PLSS: T17S, R05E, Sec. 06 (M) Acres: 0.0 Location: ALONG RIVER ROAD, 0.5 MILE SSE OF GONZALES RIVER ROAD, 5 MILES WEST OF SOLEDAD STATE PRISON. Detailed Location: Ecological: HYBRID POPULATION. General: SHAFFER SITE #242. CTS PRESENT ON 26 MAY 1991; NUMBER AND LIFESTAGE UNKNOWN. GENETIC ANALYSIS BY SHAFFER FOUND THESE CTS TO BE HYBRIDS WITH A. TIGRINUM. Owner/Manager: UNKNOWN Occurrence No. 992 Map Index: 70029 EO Index: 70882 Element Last Seen: 2007-06-14 Occ. Rank: Excellent Presence: Presumed Extant Site Last Seen: 2007-06-14 Occ. Type: Natural/Native occurrence Trend: Unknown Record Last Updated: 2007-09-26 Quad Summary: Soledad (3612143) County Summary: Monterey Lat/Long: 36.45803 / -121.31758 Accuracy: 80 meters UTM: Zone-10 N4036068 E650756 Elevation (ft): 463 PLSS: T17S, R06E, Sec. -

Inventoried Roadless Areas and Wilderness Evaluations

Introduction and Evaluation Process Summary Inventoried Roadless Areas and Wilderness Evaluations For reader convenience, all wilderness evaluation documents are compiled here, including duplicate sections that are also found in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix D Inventoried Roadless Areas. Introduction and Evaluation Process Summary Inventoried Roadless Areas Proposed Wilderness by and Wilderness Evaluations Alternative Introduction and Evaluation Process Summary Roadless areas refer to substantially natural landscapes without constructed and maintained roads. Some improvements and past activities are acceptable within roadless areas. Inventoried roadless areas are identified in a set of maps contained in the Forest Service Roadless Area Conservation Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), Volume 2, November 2000. These areas may contain important environmental values that warrant protection and are, as a general rule, managed to preserve their roadless characteristics. In the past, roadless areas were evaluated as potential additions to the National Wilderness Preservation System. Roadless areas have maintained their ecological and social values, and are important both locally and nationally. Recognition of the values of roadless areas is increasing as our population continues to grow and demand for outdoor recreation and other uses of the Forests rises. These unroaded and undeveloped areas provide the Forests with opportunities for potential wilderness, as well as non-motorized recreation, commodities and amenities. The original Forest Plans evaluated Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) data from the mid- 1980s and recommended wilderness designation for some areas. Most areas were left in a roadless, non- motorized use status. This revision of Forest Plans analyzes a new and more complete land inventory of inventoried roadless areas as well as other areas identified by the public during scoping. -

Soberanesfire Incident Update Date: 08/5/2016 Time: 7:00 A.M

SoberanesFire Incident Update Date: 08/5/2016 Time: 7:00 A.M. Fire Information Lines: 2-1-1 or 831-204-0446 Media Line: 831-484-9647 www.fire.ca.gov Inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident STATUS Incident Start Date: 07-22-2016 Incident Start Time: 8:48 a.m. Incident Type: Wildland Cause: Illegal Campfire Incident Location: Soberanes Creek, Garrapata State Park, Palo Colorado, north of Big Sur Acreage: 53,690 (32,990 CAL FIRE, 20,700 USFS) Containment: 35% Expected Containment: 08/31/2016 Injuries: 1 fatality, 2 injuries Structures Threatened: 2,000 Structures Destroyed: 57 Homes 11 Outbuildings Structures Damaged: 3 structures and 2 outbuildings RESOURCES Engines: 466 Water Tenders: 54 Helicopters: 18 Air Tankers: 6 Hand Crews: 108 Dozers: 66 Other: 4 Total Personnel: 5541 Cooperating Agencies: US Forest Service Los Padres National Forest, California State Parks and Recreation, California Highway Patrol, Monterey County Sheriff, Monterey Peninsula Regional Parks District, Red Cross, California Conservation Corps., CAL-OES, American Red Cross, California Fish and Wildlife, Carmel Highlands FPD, Monterey County Regional Fire Protection District, Mid-Coast Fire Brigade, Big Sur Volunteer Fire Brigade, CSUMB, SPCA, United Way, Pacific Gas and Electric, Monterey Bay Air Resources District, CAL TRANS, Bureau of Land Management, Monterey County EOC. SITUATION Current CAL FIRE and the United States Forest Service, Los Padres National Forest remains in unified command. Situation: Fire growth was minimal during the late evening hours due to the higher humidity and cooler temperatures. Pre-planning continues to mitigate potential future threat. Fire continues to burn in steep, rugged and inaccessible terrain. -

V. M. Seiders U.S. Geological Survey and L. E. Esparza, Charles Sabine, J

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP MF-1559-A UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERAL RESOURCE POTENTIAL OF PART OF THE VENTANA WILDERNESS AND THE BLACK BUTTE, BEAR MOUNTAIN, AND BEAR CANYON ROADLESS AREAS, MONTEREY COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SUMMARY REPORT By V. M. Seiders U.S. Geological Survey and L. E. Esparza, Charles Sabine, J. M. Spear, Scott Stebbins, and J. R. Benham U.S. Bureau of Mines STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Under the provisions of the Wilderness Act (Public Law 88-577, September 3, 1964) and related acts, the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines have been conducting mineral surveys of wilderness and primitive areas. Areas officially designated as "wilderness," "wild," or "canoe" when the act was passed were incorporated into the National Wilderness Preser vation System, and some of them are presently being studied. The act provided that areas under consideration for wilderness designation should be studied for suitability for incorporation into the Wilderness System. The mineral surveys constitute one aspect of the suitability studies. The act directs that the results of such surveys are to be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. This report discusses the results of a mineral survey of part of the Ventana Wilder ness and the Black Butte (5102), Bear Mountain (5103), and Bear Canyon (5104) Roadless Areas, Los Padres National Forest, Monterey County, California. The Ventana Wilderness was established by Public Law 91-58; this report discusses additions to the Ventana Wilderness that were established by Public Law 95-237 in 1978. -

Wild and Scenic Rivers

Wild and Scenic Rivers Background and Study Process Wild and Scenic Rivers For reader convenience, all wild and scenic study documents are compiled here, including duplicate sections that are also found in the Final Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix E Wild and Scenic Rivers. Wild and Scenic Rivers Background and Study Process Summary of Wild and Scenic Wild and Scenic Rivers River Eligibility Inventory by Forest Wild and Scenic Rivers Background and Study Process Background Congress enacted the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA) in 1968 to preserve select river's free- flowing condition, water quality and outstandingly remarkable values. The most important provision of the WSRA is protecting rivers from the harmful effects of water resources projects. To protect free- flowing character, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (which licenses nonfederal hydropower projects) is not allowed to license construction of dams, water conduits, reservoirs, powerhouses, transmission lines, or other project works on or directly affecting wild and scenic rivers (WSRs). Other federal agencies may not assist by loan, grant, and license or otherwise any water resources project that would have a direct and adverse effect on the values for which a river was designated. The WSRA also directs that each river in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (National System) be administered in a manner to protect and enhance a river's outstanding natural and cultural values. It allows existing uses of a river to continue and future uses to be considered, so long as existing or proposed use does not conflict with protecting river values. The WSRA also directs building partnerships among landowners, river users, tribal nations, and all levels of government. -

May 2013 Flannel Bush (Fremontodendron Californicum)

Obispoensis Newsletter of the San Luis Obispo Chapter of the California Native Plant Society May 2013 Flannel Bush (Fremontodendron californicum) This month’s cover drawing by Bonnie Walters is a repeat with the root crown from prolonged contact with moist of flannel bush, Fremontodendron californicum. It was soil. Summer watering (after establishment) and/or moist last used on the OBSIPOENSIS cover back in 1991. Does soil in contact with the root crown will kill it in a couple of anybody remember it? It is being reused now due to a years. The pure species in cultivation is mostly F. request Bonnie received to use some of her drawings for a mexicanum as it has the largest flowers. However, this project associated with “Learning among the Oaks” species is restricted to extreme Southern California and program. Of course, this required us to go back into our adjacent Mexico. Because of this, gardeners have created archives to find it. Also, it was obvious to us that the hybrids and selections that combine the environmental write-up that accompanied the earlier cover was clearly latitude of F. californicum with the large flowers of F. out of date. Back then the article stated that flannel bush mexicanum. Thus making the hybrids much more garden was “a member of the moderately large (65 general and friendly. Gardeners on the internet stress that flannel 1000 species) and predominantly tropical family, bushes are large plants and don’t fit well into small Sterculiaceae. The most famous member of this family by suburban settings. They also noted that the pubescence far is cacao, Theobroma cacao, the plant from which from (hairs) that shed from the twigs can be very irritating. -

Wild and Scenic Rivers the National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act (Public Law 90-542; 16 U.S.C

Wild and Scenic Rivers The National Wild & Scenic Rivers Act (Public Law 90-542; 16 U.S.C. 1271-1287) is the nation’s primary river conservation law. Enacted in 1968, the Act was specifically intended by Congress to balance the existing policy of developing rivers for their water supply, power, and other benefits, with a new policy of protecting the free flowing character and outstanding values of other rivers. The Act concluded that selected rivers and streams should be preserved in a free-flowing condition for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations. Since 1968, many rivers and streams have been added to the National Wild & Scenic Rivers System, including 16 rivers1 (and many forks and tributaries) in California, totaling more than 1,900 miles. The Wild & Scenic Rivers Act seeks to maintain a river’s free flowing character, protect and enhance outstanding natural and cultural values, and provide for public use consistent with this mandate. Designation prohibits approval or funding for new dams and diversions on designated river segments, and requires that designated rivers flowing through federal public lands be managed to protect and enhance their free flowing character and outstanding values. Where private lands are involved, the federal management agency works with local governments and property owners to develop protective measures, but the Act grants no additional federal authority over private property or local land use. Rivers are primarily added to the National System by Act of Congress, often in response to a study and recommendation submitted by a federal land management agency. To be considered for federal protection, a river must be free flowing and contain one or more outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other values (including botanical, ecological, hydrological, paleontological, scientific).