Josephus Takes Pains to Stress The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 What Are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

1 What are the Dead Sea Scrolls? Setting the Scene The ‘Dead Sea Scrolls’ is the name given first and foremost to a unique collection of nearly 900 ancient Jewish manuscripts written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. Roughly two thousand years old, they were dis- covered by chance between 1947 and 1956 in eleven caves around a ruined site called Khirbet Qumran on the north-western shore of the Dead Sea.1 Many important texts were published early on, but it was only after the release of fresh material in 1991 that most ordinary scholars gained unrestricted access to the contents of the whole corpus. The aim of this book is to explain to the uninitiated the nature and significance of these amazing manuscripts. For over fifty years now, they have had a dramatic effect on the way experts reconstruct religion in ancient Palestine.2 Cumulatively and subtly, the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) from Qumran have gradually transformed scholars’ understanding of the text of the Bible, Judaism in the time of Jesus, and the rise of Christianity. In the chapters to follow, therefore, each of these subjects will be looked at in turn, while a further chapter will deal with some of the more outlandish proposals made about the documents over the years. First of all, it will be fruitful to clear the ground by defining more carefully just what the DSS from Khirbet Qumran are. Discovery of the Century The DSS from the Qumran area have rightly been described as one of the twentieth century’s most important archaeological finds. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

The Impact of the Documentary Papyri from the Judaean Desert on the Study of Jewish History from 70 to 135 CE

Hannah M. Cotton The Impact of the Documentary Papyri from the Judaean Desert on the Study of Jewish History from 70 to 135 CE We are now in possession of inventories of almost the entire corpus of documents discovered in the Judaean Desert1. Obviously the same cannot be said about the state of publication of the documents. We still lack a great many documents. I pro- pose to give here a short review of those finds which are relevant to the study of Jewish history between 70 and 135 CE. The survey will include the state of publi- cation of texts from each find2. After that an attempt will be made to draw some interim, and necessarily tentative, conclusions about the contribution that this fairly recent addition to the body of our evidence can make to the study of differ- ent aspects of Jewish history between 70 and 135 CE. This material can be divided into several groups: 1) The first documents came from the caves of Wadi Murabba'at in 1952. They were published without much delay in 19613. The collection consists of docu- ments written in Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Arabic, and contains, among 1 For a complete list till the Arab conquest see Hannah M. Cotton, Walter Cockle, Fergus Millar, The Papyrology of the Roman Near East: A Survey, in: JRS 85 (1995) 214-235, hence- forth Cotton, Cockle, Millar, Survey. A much shorter survey, restricted to the finds from the Judaean Desert, can be found in Hannah M. Cotton, s.v. Documentary Texts, in: Encyclo- pedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, eds. -

I. the TEXTS the Archives the Babatha Archive in the Early

I. THE TEXTS Th e archives Th e Babatha archive In the early sixties of the twentieth century, an expedition, organized by the Israel Exploration Society and led by Yigael Yadin, explored a cave north of a wadi called Nahal Hever, situated on the western shore of the Dead Sea. In this three-chambered cave, skeletons and artefacts, and letters sent by Bar Kokhba, the leader of the famous Jewish revolt of the second century CE, were discovered. Th e second year of the expedi- tion brought to light another extraordinary fi nd. I quote from Yadin’s report: In one of the water skins a large collection of balls of fl ax thread and a well packed parcel were found. Th e outer wrapping of the parcel consisted of a sack carefully fastened with a twisted rope; inside there was a leather case with many papyri packed tightly together. When the parcel was opened, it was found to contain the archive of Babatha the daughter of Simeon.1 An archive is a set of documents, belonging to one family and oft en, for convenience’s sake, named aft er one person, who either features in the majority of the documents or to whom most other persons men- tioned are somehow related. In our case this is Babatha, the daughter of Simeon.2 Because the papyri were found in the original wrapping in 1 See Yigael Yadin, “Expedition D—Th e Cave of Letters,” IEJ 12 (1962): 231. For a short description of the circumstances of the fi nd see R. -

Book Reviews

18-BookReviews JETS 42.3 Page 477 Friday, August 27, 1999 3:58 PM JETS 42/3 (September 1999) 477–555 BOOK REVIEWS Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Edited by Leland Ryken, James C. Wilhoit, and Tremper Longman III. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 1998, xxi + 1058, $39.99. Initially one ˜nds some irony in the fact that an inherently left-brained genre—the dictionary—was chosen to promote a right-brained approach to the Bible, the very approach consciously taken by this new and highly touted reference work from Inter- Varsity (henceforth DBI). The book contains a number of attractive features, but it retains signi˜cant weaknesses that may threaten its longevity as “an indispensable reference tool” (in the words of the preface). More on these shortly. According to the editors, the purview of the DBI is “the imagery, metaphors and archetypes of the Bible,” terms for which the introduction gives extensive de˜nitions. There is a wide spectrum of topics, including each book of the Bible, most major Biblical characters, many topics that one would ˜nd in standard Bible dictionaries (e.g. heaven, sacri˜ce), as well as a number with a literary ˘avor (e.g. plot motifs, travel stories). Happily, most of the articles possess an appropriate and readable length. Irksomely, all of them are unsigned (a list of contributors resides at the front), since the editors, we discover in the preface, had to revise “the vast majority” of them and leave their own mark upon many of the entries, sometimes at the expense of the original author’s. The book’s attractive features start with its title. -

Hanan Eshel - List of Publications

Hanan Eshel - List of Publications Books and Monographs 1. With D. Amit. The Bar-Kokhba Refuge Caves. Tel Aviv: Israel Exploration Society, 1998 (Hebrew). 2. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonaean State. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2004 (Hebrew). 3. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans and Yad Ben-Zvi, 2008. 4. Qumran: Scrolls, Caves and History, A Carta Field Guide, Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 5. Qumran: Scrolls, Caves and History, A Carta Field Guide, Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew). 6. Masada: An Epic Story, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 7. Masada: An Epic Story, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew) 8. Ein Gedi: Oasis and Refuge, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 9. Ein Gedi: Oasis and Refuge, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew). 10. With R. Porat. Refuge Caves of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Jerusalem, Israel Exploration Society, 2009 (Hebrew). 11. Editor with D. Amit. The Hasmonean State. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 1995 (Hebrew). 12. Editor with J. Charlesworth, N. Cohen, H. Cotton, E. Eshel, P. Flint, H. Misgav, M. Morgenstern, K. Murphy, M. Segal, A. Yardeni and B. Zissu, Miscellaneous Texts from the Judaean Desert, DJD 38. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. 13. Editor with B. Zissu. New Studies on the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Proceedings of the 21th Annual Conference of the Department of Land of Israel Studies, Ramat Gan: Department of Land of Israel Studies, 2001 (Hebrew). 14. Editor with E. Stern. The Samaritans. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2002 (Hebrew). 15. Editor with A.I. -

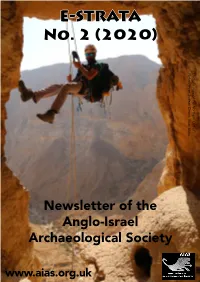

E-STRATA No. 2 (2020)

E-STRATA No. 2 (2020) Nahal Hever, Judean Desert, Eitan Klein. Eitan Desert, Judean Hever, Nahal Photo: survey of the Northern Cliff of NorthernCliff the of survey Photo: Newsletter of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society www.aias.org.uk E-STRATA No. 2 (2020) IN THIS ISSUE In the News 2 In Conversation with Eitan Klein 18 Nick Slope’s Adventures from the Holy Land 26 Tailpiece 31 Dear Friends, As autumn peers towards winter, we are delighted to bring you E-Strata 2 for cosy days and nights indoors. Despite the New Old that continues to challenge the world, including excavations in Israel, archaeologists, historians and museum curators are still weaving a rich tapestry to re-write and re-address what we know about the ancient Near East. So we’re able to share 16 pages of news. And the floodgates continue to give. As we go to press, an 8th or 7th century BCE ‘palace’ has turned up in the East Talpiot district of Jerusalem with perfectly preserved stone col- umn capitals. The first cluster of deep-sea shipwrecks off Israel has beeen discovered in the Leviathan gas field, dating back to the Late Bronze Age. A hoard of 425 golden Abbasid coins from the 9th century are gleaming in an undisclosed location in central Israel. May the discoveries continue on land, sea and library shelves. E-Strata is fortunate to have caught up with Dr Eitan Klein, a committee member of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. Eitan is the Deputy Director of the Antiquities Theft Prevention Unit at the Israel Antiquities Authority and lifts the lid on the struggle to con- tain site looting and talks about his latest work with the Judean Desert Caves Project. -

Old and New in the Documentary Papyri from the Bar Kokhba Period

Old and New in the Documentary Papyri from the Bar Kokhba Period Hillel I. Newman Yigael Yadin, Jonas C. Greenfield, Ada Yardeni, Baruch A. Levine (eds.), The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters: Hebrew, Aramaic and Nabatean-Aramaic Papyri (with additional contributions by Hannah Μ. Cotton and Joseph Naveh), Judean Desert Studies III. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2002. xviii + 422 pp. ISBN 965-221 -046-3 Few volumes of texts from the Judean Desert have generated as much anticipation among scholars as The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave o f Letters: Hebrew, Aramaic and Nabatean-Aramaic Papyri (henceforth: Documents), and that is saying a great deal. The collection contains thirty documents, ranging in date from 93/94 CE to the third year of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. When the papyri themselves (now known as Ρ. Yadin) were discovered by Yigael Yadin and his team in the course of two seasons of excavations in Nahal Hever (1960-61), no one could have foreseen the various delays which would beset the project. Surely the most tragic were the untimely deaths of two of the primary editors: Yadin himself in 1984 and Jonas Greenfield in 1995. The material was entrusted to Ada Yardeni and Baruch Levine for completion, and to them we all owe a special debt. The ‘mere’ task of deciphering and transcribing the cursive scripts in these papyri is so daunting (as any non-specialist who has tried his or her hand at it can attest), that Ada Yardeni’s artful presentation of the material is nothing short of astonishing.1 While the texts and translations of the Hebrew and Aramaic (including Nabatean Aramaic) documents have all been in the public domain since die appearance in 2000 of Yardeni’s massive paleographic study of documentary texts from the Judean Desert,2 the new volume presents in painstaking detail not only the paleographic and philological rationale for the contents of that edition, but also a general introduction to various as pects of the papyri and an extensive commentary touching on countless points of inter pretation. -

The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel and Peter Schäfer 100 The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered New Perspectives on the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome Edited by PETER SCHÄFER Mohr Siebeck In Memoriam Leo Mildenberg 1913-2001 ISBN 3-16-148076-7 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) The Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnd.ddh.de © 2003 by J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), PO. Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. This book was typeset by epline in Kirchheim, printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Table of Contents Peter Schäfer Preface VII Peter Schäfer Bar Kokhba and the Rabbis 1 Martin Goodman Trajan and the Origins of the Bar Kokhba War 23 Yoram Tsafrir Numismatics and the Foundation of Aelia Capitolina: A Critical Review 31 Benjamin Isaac Roman Religious Policy and the Bar Kokhba War 37 Aharon Oppenheimer The Ban of Circumcision as a Cause of the Revolt: A Reconsideration 55 Ra'anan Abusch Negotiating Difference: Genital Mutilation in Roman Slave Law and the History of the Bar Kokhba Revolt ... 71 Hanan Eshel The Dates Used during the Bar Kokhba Revolt 93 Menahem Mor The Geographical Scope of the Bar Kokhba Revolt 107 Hannah M. -

Hannah M. Cotton

Hannah M. Cotton Some Aspects of the Roman Administration of Judaea/Syria-Palaestina This paper falls into two parts: in the first part I discuss the provincialization of the territory that came to be called the province of Judaea, and later Syria-Palaes- tina1; in the second part I look at the administration of the so-called Jewish re- gion' of Judaea in the light of the recently published documents from the Judaean Desert. I Judaea came under direct Roman rule only in 6 CE with the exile of Herod's son, the Tetrarch Archelaus. From the conquest of Judaea by Pompey in 63 BCE until 6 CE, Judaea was ruled first by descendants of the Hasmonaean house without royal title and later by the Herodian dynasty. Pompey reduced the extent of Jew- ish territory by annexing all the coastal cities and those of the Decapolis to the new province of Syria2. Judaea included then Judaea proper, Idumaea, Samaria, the Peraea and the Galilee. Under Herod the districts of Batanea, the Trachonitis and Auranitis were added to his kingdom3. After Herod's death the kingdom was divided between his three sons. Archelaus had Judaea proper, Idumaea, and Sama- ria including the cities of Caesarea, Samaria-Sebaste, Jerusalem and Joppa - this part came under direct Roman rule upon his exile in 6 CE. Philip received Bat- anea, the Trachonitis and Auranitis — districts with mixed population where the non-Jewish element prevailed. It is little wonder that after his death they were attached to the province of Syria. Herod Antipas received the Galilee and the Peraea. -

The Relationship Between Roman and Local Law in the Babatha And

Th e Relationship between Roman and Local Law in the Babatha and Salome Komaise Archives OUDSHOORN_f1_i-xiv.indd i 6/29/2007 7:54:45 PM Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah Edited by Florentino García Martínez Associate Editors Peter W. Flint Eibert J.C. Tigchelaar VOLUME LXIX OUDSHOORN_f1_i-xiv.indd ii 6/29/2007 7:54:45 PM Th e Relationship between Roman and Local Law in the Babatha and Salome Komaise Archives General Analysis and Th ree Case Studies on Law of Succession, Guardianship and Marriage by Jacobine G. Oudshoorn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 OUDSHOORN_f1_i-xiv.indd iii 6/29/2007 7:54:45 PM Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Oudshoorn, Jacobine G. Th e Relationship between Roman and local law in the Babatha and Salome Komaise archives : general analysis and three case studies on law of succession, guardianship, and marriage / by Jacobine G. Oudshoorn. p. cm. — (Studies on the texts of the desert of Judah ; v. 69) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-14974-8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Jewish law—History—Sources 2. Roman law—History—Sources. 3. Domestic relations (Jewish law) 4. Domestic relations (Roman law) 5. Dead Sea scrolls. 6. Manuscripts, Hebrew (Papyri) I. Title. II. Series. KB197.2.093 2007 340.5'3948—dc22 2007026970 ISSN: 0169-9962 ISBN: 978 90 04 14974 8 Copyright 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

Nature and the Origin of Ein Feshcha Springs (NW Dead Sea)

Nature and the Origin of Ein Feshcha Springs (NW Dead Sea) By Jawad Ali Hasan From Jerusalem / Palestine A thesis for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences submitted to the Faculty of Civil Engineering, Geosciences and Environmental Sciences University of Karlsruhe, Germany Date of thesis defense: 04.02. 2009 Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Heinz Hötzl, Karlsruhe University Prof. Dr. Akiva Flexer, Tel Aviv University Prof. Dr. Amer Marei, Al-Quds University Declaration i Declaration I hereby certify and confirm that this thesis is entirely the result of my own work and that no other than the cited aid and sources have been used. Erklärung Hiermit bestätige ich, dass die vorliegende Dissertatious-Arbeit selbstständig und nur unter Verwendung der genannten Hilfsmittel angefertigt wurde (Jawad Ali Hasan) Karlsruhe, February 2009 DEDICATION ii Wxw|vtà|ÉÇ gÉ Åç ÅÉà{xÜ tÇw ytà{xÜ ã{É áâÑÑÉÜàxw Åx tÇw Ä|z{àá âÑ Åç Ä|yx á|Çvx Åç u|Üà{ àÉ à{|á wtàx gÉ Åç ÄÉäxÄç ã|yx Â`|áátÊ yÉÜ {xÜ xyyÉÜàá? ÅÉÜtÄ áâÑÑÉÜà tÇw xÇwÄxáá xÇvÉâÜtzxÅxÇà gÉ Åç v{|ÄwÜxÇ? yÉÜ à{xÜx âÇwxÜáàtÇw|Çz wâÜ|Çz Åç tuáxÇvx? ã|à{ Åç ÄÉäx àÉ à{xÅ tÄÄA ]tãtw ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This piece of research took a lot of efforts by many people whom I am acknowledging in this dissertation, and will also carry their kindness and support with me when I build my professional life. This support by my professors, colleagues, and friends, was translated through different ways. I was very lucky to receive the wonderful encouragement from all, in addition to financial and psychological support.