Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 What Are the Dead Sea Scrolls?

1 What are the Dead Sea Scrolls? Setting the Scene The ‘Dead Sea Scrolls’ is the name given first and foremost to a unique collection of nearly 900 ancient Jewish manuscripts written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. Roughly two thousand years old, they were dis- covered by chance between 1947 and 1956 in eleven caves around a ruined site called Khirbet Qumran on the north-western shore of the Dead Sea.1 Many important texts were published early on, but it was only after the release of fresh material in 1991 that most ordinary scholars gained unrestricted access to the contents of the whole corpus. The aim of this book is to explain to the uninitiated the nature and significance of these amazing manuscripts. For over fifty years now, they have had a dramatic effect on the way experts reconstruct religion in ancient Palestine.2 Cumulatively and subtly, the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) from Qumran have gradually transformed scholars’ understanding of the text of the Bible, Judaism in the time of Jesus, and the rise of Christianity. In the chapters to follow, therefore, each of these subjects will be looked at in turn, while a further chapter will deal with some of the more outlandish proposals made about the documents over the years. First of all, it will be fruitful to clear the ground by defining more carefully just what the DSS from Khirbet Qumran are. Discovery of the Century The DSS from the Qumran area have rightly been described as one of the twentieth century’s most important archaeological finds. -

Josephus Takes Pains to Stress The

316 BOOK REVIEWS elsewhere, ‘Josephus takes pains to stress the accomplishments of his biblical heroes by deemphasizing the role of G-d in their actual achievements’), it is not Feldman’s fault that Josephus is serving two masters. That is the way it was for Jews who wished to survive in the first century. We should be very grateful to Louis Feldman — for whom ‘on the one hand’ and ‘on the other hand’, ‘however’ and ‘to be sure’ are among the most common phrases — who has so thoroughly analyzed this difficult material, which pulls in so many directions, and laid it out so clearly. Daniel R. Schwartz The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Hannah Μ. Cotton and Ada Yardeni eds., Aramaic, Hebrew and Greek Documentary Texts from Nahal Hever and Other Sites with an Appendix Containing Alleged Qumran Texts (The Seiyâl Collection II), Discoveries in the Judaean Desert XXVH, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1997. xxiii + 381 pp. + 33 figures + 61 plates. ISBN 0-19-82695-3. The sumptuous and attractive volume under review contains the full publication of several dozen papyri from the Judaean Desert. These are all documentary texts, as the term is used by papyrologists in contradistinction to literary texts. That is to say, they were written to be read by a limited number of potential readers, not for publication. In this volume, specifically, we have mainly legal documents — marriage docu ments, loans, sales, and the like — as well as a few lists and one or two letters. The explicitly dated Aramaic documents all fall in the narrow range of 131-134/5 CE; those datable by palaeography could range up to two centuries earlier. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

Pdf (Accessed 9 September 2019)

REFORMED FAITH & PRACTICE Volume 4 Number 3 December 2019 A Model of a True Theologian / 3 Celebrating the First Testament Philip Graham Ryken / 4-19 Recovering the Song of Songs as a Christian Text Liam Goligher / 20-30 The Hermit Who Saved the Hebrew Truth John D. Currid / 31-36 Martin Luther's Doctrine of Temptation Howard Griffith / 37-62 Geerhardus Vos's Thomistic Doctrine of Creation J. V. Fesko / 63-79 Columbia Old and New Sean Michael Lucas / 80-88 Book Reviews / 89-95 REFORMED FAITH & PRACTICE THE JOURNAL OF REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY J. Ligon Duncan III, Chancellor Robert J. Cara, Provost Edited for the faculty of RTS by John R. Muether Associate Editors Michael Allen Thomas Keene James N. Anderson Miles V. Van Pelt Richard P. Belcher, Jr. Guy Prentiss Waters Editorial Assistant: Angel G. Roman REFORMED FAITH & PRACTICE is published three times per year and is distributed electronically for free. Copyright 2019 Reformed Theological Seminary. All rights reserved. REFORMED FAITH & PRACTICE 1231 Reformation Drive Oviedo, FL 32765 ISSN 2474-9109 Reformed Theological Seminary Atlanta ∙ Charlotte ∙ Dallas ∙ Houston ∙ Jackson ∙ New York City ∙ Orlando ∙ Washington, D.C. ∙ Global 2 Reformed Faith & Practice 4:3 (2019): 3 A Model of a True Theologian: Howard Griffith, 1954-2019 When the RTS Orlando library inherited the vast personal library of Roger Nicole, among its 20,000 volumes was a small Banner of Truth publication that was a gift to Dr. Nicole. A grateful student, having recently graduated from Gordon- Conwell Theological Seminary, inscribed the following on November 10, 1982: Dr. Nicole, Thank you so much for the great help you have been in the formulation of my theological thinking and my outlook on the wonderful grace of God. -

SPRING 2010 Dearwheaton

This version of Wheaton magazine does not contain the Class News section. s p r i n g 2 0 1 0 WHEATON The Litfin Legacy Continuity Amid Growth President Duane Litfin retires after 17 years Inside: Science Station Turns 75 • Remembering President Armerding • The Promise Report 150.WHEATON.EDU Wheaton College exists to help build the church and improve society worldwide by promoting the development of whole and effective Christians through excellence in programs of Christian higher education. This mission expresses our commitment to do all things “For Christ and His Kingdom.” volume 14 i s s u e 2 s PR i N G 2 0 1 0 6 a l u m n i n e w s departments 32 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters Open letter from Tim Stoner ’82, 5 News president of the Alumni Board 10 Sports 33 Wheaton Alumni Association News Association news and events 27 The Promise Report 37 Alumni Class News 56 Authors Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts from published alumnus Walter Wolfram ’63 Cover photo: President Litfin enjoys the lively bustle of the Sports and A Sentimental Journey Recreation Complex that was built in 2000 as a result of the New 58 Century Challenge. The only “brick-and-mortar” part of that campaign, An archival reflection from an alumna the SRC features a large weight room, three gyms, a pool, elevated Faculty Voice running track, climbing wall, dance and fitness studio, and wrestling 60 room, as well as classrooms, conference rooms, and a physiology lab. Dr. Nadine Folino-Rorem mentors biology Dr. -

The Impact of the Documentary Papyri from the Judaean Desert on the Study of Jewish History from 70 to 135 CE

Hannah M. Cotton The Impact of the Documentary Papyri from the Judaean Desert on the Study of Jewish History from 70 to 135 CE We are now in possession of inventories of almost the entire corpus of documents discovered in the Judaean Desert1. Obviously the same cannot be said about the state of publication of the documents. We still lack a great many documents. I pro- pose to give here a short review of those finds which are relevant to the study of Jewish history between 70 and 135 CE. The survey will include the state of publi- cation of texts from each find2. After that an attempt will be made to draw some interim, and necessarily tentative, conclusions about the contribution that this fairly recent addition to the body of our evidence can make to the study of differ- ent aspects of Jewish history between 70 and 135 CE. This material can be divided into several groups: 1) The first documents came from the caves of Wadi Murabba'at in 1952. They were published without much delay in 19613. The collection consists of docu- ments written in Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Arabic, and contains, among 1 For a complete list till the Arab conquest see Hannah M. Cotton, Walter Cockle, Fergus Millar, The Papyrology of the Roman Near East: A Survey, in: JRS 85 (1995) 214-235, hence- forth Cotton, Cockle, Millar, Survey. A much shorter survey, restricted to the finds from the Judaean Desert, can be found in Hannah M. Cotton, s.v. Documentary Texts, in: Encyclo- pedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls, eds. -

I. the TEXTS the Archives the Babatha Archive in the Early

I. THE TEXTS Th e archives Th e Babatha archive In the early sixties of the twentieth century, an expedition, organized by the Israel Exploration Society and led by Yigael Yadin, explored a cave north of a wadi called Nahal Hever, situated on the western shore of the Dead Sea. In this three-chambered cave, skeletons and artefacts, and letters sent by Bar Kokhba, the leader of the famous Jewish revolt of the second century CE, were discovered. Th e second year of the expedi- tion brought to light another extraordinary fi nd. I quote from Yadin’s report: In one of the water skins a large collection of balls of fl ax thread and a well packed parcel were found. Th e outer wrapping of the parcel consisted of a sack carefully fastened with a twisted rope; inside there was a leather case with many papyri packed tightly together. When the parcel was opened, it was found to contain the archive of Babatha the daughter of Simeon.1 An archive is a set of documents, belonging to one family and oft en, for convenience’s sake, named aft er one person, who either features in the majority of the documents or to whom most other persons men- tioned are somehow related. In our case this is Babatha, the daughter of Simeon.2 Because the papyri were found in the original wrapping in 1 See Yigael Yadin, “Expedition D—Th e Cave of Letters,” IEJ 12 (1962): 231. For a short description of the circumstances of the fi nd see R. -

View Task Force (RTF) to Review the Events Surrounding the Separation of Dr

1617-055 Wheaton Mag- Cover.indd FC2 V OLUME 20 // ISSUE 1 // 2017 CULTIVATING A DEEP LOVE FOR CHRIST AND HIS KINGDOM P. 6 and Center The Faith Neuroscience WHEATON NewArmerding theArts for The Music Hundred Holmes and 11/15/16 4:36 PM The best way to experience the invaluable education available at Wheaton is by being bold enough to ask hard questions and step beyond your comfort zone. Wheaton’s warm community and Christ-centered mission make it an excellent place to do just that.” —Peter D. ’16 As alumni and friends of Wheaton, you play a critical role in helping us identify the best and brightest students to refer to the College. We value your input and invite you to join us in the recruitment process once again. To refer a student who will take full advantage of the Wheaton Experience, please let us know at wheaton.edu/refer. To share stories from current Wheaton students and links to valuable content that will help guide prospective students as they navigate their college search journey, go to blog.wheaton.edu. 1617-055 Wheaton Mag - FOB.indd IFC1 11/22/16 9:06 AM featuresVOLUME 20 // ISSUE 1 WINTER 2017 WHEATON “All truth is God’s truth.” Facebook facebook.com/ FROM THE HEART, ART: wheatoncollege.il FOR THE KINGDOM ZACHARY ERWIN ’17 / 21 / 32 Twitter twitter.com/ wheatoncollege ➝ THE HOLMES NEUROSCIENCE HUNDRED / 30 AND FAITH / 34 Instagram courtesy of the Wheaton College Archives, Buswell Library of the Wheaton courtesy instagram.com/ Photo wheatoncollegeil WHEATON.EDU/MAGAZINE 1 1617-055 Wheaton Mag - FOB.indd 1 11/16/16 3:02 PM SECTION NAME HERE VOLUME 20 // ISSUE 1 WINTER 2017 WHEATON 2 Is Wheaton in your plans? Provide for Wheaton College’s ministry through your estate plans. -

Spring 2019 Academic Catalog

IVP ACADEMIC CATALOG SPRING 2019 AVAILABLE MARCH 2019 AVAILABLE APRIL 2019 These two new titles are a part of the joint publishing venture between IVP Academic and the Christian Association for Psychological Studies that aims to promote the understanding of the relationship between Christianity and the behavioral sciences. SEE PAGES 25 AND 26 FOR MORE INFORMATION. MEET IVP ACADEMIC G E T Y O U R IVP Academic publishes books that facilitate meaningful conversations across the academy 40% PROFESSIONAL DISCOUNT and the church. We partner with leaders at colleges and universities to provide thoughtful resources for engaging with the Christian faith and its world-changing implications. OUR HISTORY IVP Academic is the academic imprint of InterVarsity Press, the publishing branch of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. As an affiliate of this campus ministry, we have been publishing for students, professors, scholars, and church leaders for over seventy years. Although our breadth of authors and offerings has expanded, we maintain the same evangelical commitment to education and transformation. We publish across a wide range of disciplines beyond theology and biblical studies, including strong programs in psychology, philosophy, and missiology, with additional resources in history, business, economics, science, and apologetics. + WHO WE ARE At IVP Academic we want to partner with leaders in the academy to provide quality resources for current scholarship and for training the next generation of scholars. JEFF JON CINDY DAVID CROSBY BOYD BUNCH M -

Winter 2011 WHEATON

For privacy reasons, this online edition of Wheaton magazine does not contain the Class News section. Subsequently, this page is left blank due to the revised layout. winter 2011 WHEATON The Inauguration Wheaton’s eighth president, Dr. Philip Graham Ryken Inside: President Chase Remembered • BRIDGE to Diversity • Science Center Dedication 82306_BCFC_IFC01.indd 1 11/19/10 8:10 PM Wheaton College exists to help build the church and improve society worldwide by promoting the development of whole and effective Christians through excellence in programs of Christian higher education. This mission expresses our commitment to do all things “For Christ and His Kingdom.” volume 14 issue 1 WiNTe R 2011 14 22 alumni news departments 34 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters Dr. R. Mark Dillon, vice president for advancement and alumni relations 4 News 35 Wheaton Alumni Association News 10 Sports Association news and events 29 The Promise Report Alumni Class News 40 56 Authors Books by Wheaton’s faculty, a column by published alumna, Keri Wyatt Kent ’85. Cover photo: Cover photo: Dr. Philip G. Ryken stands at his Readings inauguration, immediately following the investiture by Trustee Board 58 Chairman Dr. David Gieser ’71: “With the firm assurance that you have A poem by Robert Siegel ’61 celebrates the come in the revealed will and perfect timing of the Triune God, I Inauguration. declare that you are the eighth President of Wheaton College having 60 Faculty Voice been duly chosen. Whom we appoint, may God anoint with all the Dr. Wayne Martindale reveals why literature needed blessings for the sanctified task now before you.” Photo by means so much to him. -

Hanan Eshel - List of Publications

Hanan Eshel - List of Publications Books and Monographs 1. With D. Amit. The Bar-Kokhba Refuge Caves. Tel Aviv: Israel Exploration Society, 1998 (Hebrew). 2. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonaean State. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2004 (Hebrew). 3. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans and Yad Ben-Zvi, 2008. 4. Qumran: Scrolls, Caves and History, A Carta Field Guide, Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 5. Qumran: Scrolls, Caves and History, A Carta Field Guide, Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew). 6. Masada: An Epic Story, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 7. Masada: An Epic Story, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew) 8. Ein Gedi: Oasis and Refuge, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009. 9. Ein Gedi: Oasis and Refuge, A Carta Field Guide. Jerusalem: Carta, 2009 (Hebrew). 10. With R. Porat. Refuge Caves of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Jerusalem, Israel Exploration Society, 2009 (Hebrew). 11. Editor with D. Amit. The Hasmonean State. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 1995 (Hebrew). 12. Editor with J. Charlesworth, N. Cohen, H. Cotton, E. Eshel, P. Flint, H. Misgav, M. Morgenstern, K. Murphy, M. Segal, A. Yardeni and B. Zissu, Miscellaneous Texts from the Judaean Desert, DJD 38. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. 13. Editor with B. Zissu. New Studies on the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Proceedings of the 21th Annual Conference of the Department of Land of Israel Studies, Ramat Gan: Department of Land of Israel Studies, 2001 (Hebrew). 14. Editor with E. Stern. The Samaritans. Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2002 (Hebrew). 15. Editor with A.I. -

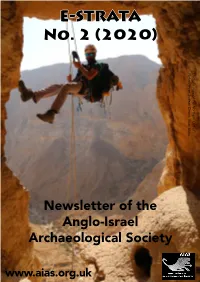

E-STRATA No. 2 (2020)

E-STRATA No. 2 (2020) Nahal Hever, Judean Desert, Eitan Klein. Eitan Desert, Judean Hever, Nahal Photo: survey of the Northern Cliff of NorthernCliff the of survey Photo: Newsletter of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society www.aias.org.uk E-STRATA No. 2 (2020) IN THIS ISSUE In the News 2 In Conversation with Eitan Klein 18 Nick Slope’s Adventures from the Holy Land 26 Tailpiece 31 Dear Friends, As autumn peers towards winter, we are delighted to bring you E-Strata 2 for cosy days and nights indoors. Despite the New Old that continues to challenge the world, including excavations in Israel, archaeologists, historians and museum curators are still weaving a rich tapestry to re-write and re-address what we know about the ancient Near East. So we’re able to share 16 pages of news. And the floodgates continue to give. As we go to press, an 8th or 7th century BCE ‘palace’ has turned up in the East Talpiot district of Jerusalem with perfectly preserved stone col- umn capitals. The first cluster of deep-sea shipwrecks off Israel has beeen discovered in the Leviathan gas field, dating back to the Late Bronze Age. A hoard of 425 golden Abbasid coins from the 9th century are gleaming in an undisclosed location in central Israel. May the discoveries continue on land, sea and library shelves. E-Strata is fortunate to have caught up with Dr Eitan Klein, a committee member of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. Eitan is the Deputy Director of the Antiquities Theft Prevention Unit at the Israel Antiquities Authority and lifts the lid on the struggle to con- tain site looting and talks about his latest work with the Judean Desert Caves Project.