Disintegration of Sasanian Hegemony Over Northern Iran (Ad 623-643)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

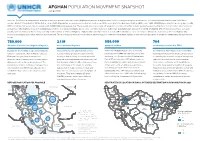

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire

4/12/2012 Lecture 27 Sasanian Empire HIST 213 Spring 2012 Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE) Successors of the Achaemenids 224 CE Ardashir I • a descendant of Sasan – gave his name to the new Sasanian dynasty, • defeated the Parthians • The Sasanians saw themselves as the successors of the Achaemenid Persians. 1 4/12/2012 Shapur I (r. 241–72 CE) • One of the most energetic and able Sasanian rulers • the central government was strengthened • the coinage was reformed • Zoroastrianism was made the state religion • The expansion of Sasanian power in the west brought conflict with Rome Shapur I the Conqueror • conquers Bactria and Kushan in east • led several campaigns against Rome in west Penetrating deep into Eastern-Roman territory • conquered Antiochia (253 or 256) Defeated the Roman emperors: • Gordian III (238–244) • Philip the Arab (244–249) • Valerian (253–260) – 259 Valerian taken into captivity after the Battle of Edessa – disgrace for the Romans • Shapur I celebrated his victory by carving the impressive rock reliefs in Naqsh-e Rostam. Rome defeated in battle Relief of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rostam, showing the two defeated Roman Emperors, Valerian and Philip the Arab 2 4/12/2012 Terry Jones, Barbarians (BBC 2006) clip 1=9:00 to end clip 2 start - … • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_WqUbp RChU&feature=related • http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&featu re=endscreen&v=QxS6V3lc6vM Shapur I Religiously Tolerant Intensive development plans • founded many cities, some settled in part by Roman emigrants. – included Christians who could exercise their faith freely under Sasanian rule • Shapur I particularly favored Manichaeism – He protected Mani and sent many Manichaean missionaries abroad • Shapur I befriends Babylonian rabbi Shmuel – This friendship was advantageous for the Jewish community and gave them a respite from the oppressive laws enacted against them. -

A Historical Contextual Analysis Study of Persian Silk Fabric: (Pre-Islamic Period- Buyid Dynasty)

Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2017- 4th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities 10-12 July 2017- Dubai, UAE A HISTORICAL CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS STUDY OF PERSIAN SILK FABRIC: (PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD- BUYID DYNASTY) Nadia Poorabbas Tahvildari1, Farinaz Farbod2, Azadeh Mehrpouyan3* 1Alzahra University, Art Faculty, Tehran, Iran and Research Institute of Cultural Heritage & Tourism, Traditional Art Department, Tehran, IRAN, [email protected] 2Alzahra University, Art Faculty, Tehran, IRAN, [email protected] 3Department of English Literature, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, IRAN, email: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract This paper explores the possibility existence of Persian silk fabric (Diba). The study also identifies the locations of Diba weave and its production. Based on the detailed analysis of Dida etymology and discovery locations, this paper present careful classification silk fabrics. Present study investigates the characteristics of Diba and introduces its sub-divisions from Pre-Islamic period to late Buyid dynasty. The paper reports the features of silk fabric of Ancient Persian, silk classification of Sasanian Empire based on discovery location, and silk sub-divisions of Buyaid dynasty. The results confirm the existence of Diba and its various types through a historical contextual analysis. Keywords: Persian Silk, Diba, Silk classification, Historical, context, location, Sasanian Empire 1. INTRODUCTION Diba is one of the machine woven fabrics (Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism, 2009) which have been referred continuously as one of the exquisite silk fabrics during the history. History of weaving in Iran dated back to millenniums AD. The process of formation, production and continuity of this art in history of Iran took advantages of several factors such as economic, social, cultural and ecological factors. -

Fort Leavenworth Ethics Symposium

Fort Leavenworth Ethics Symposium Ethical and Legal Issues in Contemporary Conflict Symposium Proceedings Frontier Conference Center Fort Leavenworth, Kansas November 16-18, 2009 Edited by Mark H. Wiggins and Ted Ihrke Co-sponsored by the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College and the Command and General Staff College Foundation, Inc. Special thanks to our key corporate sponsor Other supporting sponsors include: Published by the CGSC Foundation Press 100 Stimson Ave., Suite 1149 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027 Copyright © 2010 by CGSC Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. www.cgscfoundation.org Papers included in this symposium proceedings book were originally submitted by military officers and other subject matter experts to the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The CGSC Foundation/CGSC Foundation Press makes no claim to the authors’ copyrights for their individual work. ISBN 978-0-615-36738-5 Layout and design by Mark H. Wiggins MHW Public Relations and Communications Printed in the United States of America by Allen Press, Lawrence, Kansas iv Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... ix Foreword by Brig. Gen. Ed Cardon, Deputy Commandant, CGSC & Col. (Ret.) Bob Ulin, CEO, CGSC Foundation ......................................................................... xi Symposium Participants ............................................................................................................ -

Download This PDF File

ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 8, No. 2, 2012, pp. 132-139 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.css.1923669720120802.1985 www.cscanada.org Iranian People and the Origin of the Turkish-speaking Population of the North- western of Iran LE PEUPLE IRANIEN ET L’ORIGINE DE LA POPULATION TURCOPHONE AU NORD- OUEST DE L’IRAN Vahid Rashidvash1,* 1 Department of Iranian Studies, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, exception, car il peut être appelé une communauté multi- Armenia. national ou multi-raciale. Le nom de Azerbaïdjan a été *Corresponding author. l’un des plus grands noms géographiques de l’Iran depuis Received 11 December 2011; accepted 5 April 2012. 2000 ans. Azar est le même que “Ashur”, qui signifi e feu. En Pahlavi inscriptions, Azerbaïdjan a été mentionnée Abstract comme «Oturpatekan’, alors qu’il a été mentionné The world is a place containing various racial and lingual Azarbayegan et Azarpadegan dans les écrits persans. Dans groups. So that as far as this issue is concerned there cet article, la tentative est faite pour étudier la course et is no difference between developed and developing les gens qui y vivent dans la perspective de l’anthropologie countries. Iran is not an exception, because it can be et l’ethnologie. En fait, il est basé sur cette question called a multi-national or multi-racial community. que si oui ou non, les gens ont résidé dans Atropatgan The name of Azarbaijan has been one of the most une race aryenne comme les autres Iraniens? Selon les renowned geographical names of Iran since 2000 years critères anthropologiques et ethniques de personnes dans ago. -

The Depiction of the Arsacid Dynasty in Medieval Armenian Historiography 207

Azat Bozoyan The Depiction of the ArsacidDynasty in Medieval Armenian Historiography Introduction The Arsacid, or Parthian, dynasty was foundedinthe 250s bce,detaching large ter- ritories from the Seleucid Kingdom which had been formed after the conquests of Alexander the Great.This dynasty ruled Persia for about half amillennium, until 226 ce,when Ardashir the Sasanian removed them from power.Under the Arsacid dynasty,Persia became Rome’smain rival in the East.Arsacid kingsset up theirrel- ativesinpositions of power in neighbouringstates, thus making them allies. After the fall of the Artaxiad dynasty in Armenia in 66 ce,Vologases IofParthia, in agree- ment with the RomanEmpire and the Armenian royal court,proclaimed his brother Tiridates king of Armenia. His dynasty ruled Armenia until 428 ce.Armenian histor- iographical sources, beginning in the fifth century,always reserved aspecial place for that dynasty. MovsēsXorenacʽi(Moses of Xoren), the ‘Father of Armenian historiography,’ at- tributed the origin of the Arsacids to the Artaxiad kingswho had ruled Armenia be- forehand. EarlyArmenian historiographic sources provide us with anumber of tes- timoniesregarding various representativesofthe Arsacid dynasty and their role in the spread of Christianity in Armenia. In Armenian, as well as in some Syriac histor- ical works,the origin of the Arsacids is related to King AbgarVof Edessa, known as the first king to officiallyadopt Christianity.Armenian and Byzantine historiograph- ical sources associate the adoption of Christianity as the state religion in Armenia with the Arsacid King Tiridates III. Gregory the Illuminator,who playedamajor role in the adoption of Christianity as Armenia’sstate religion and who even became widelyknown as the founder of the Armenian Church, belongstoanother branch of the samefamily. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

Persian Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY PERSIAN ROYAL ANCESTRY Achaemenid Dynasty from Greek mythical Perses, (705-550 BC) یشنماخه یهاشنهاش (Achaemenid Empire, (550-329 BC نايناساس (Sassanid Empire (224-c. 670 INTRODUCTION Persia, of which a large part was called Iran since 1935, has a well recorded history of our early royal ancestry. Two eras covered are here in two parts; the Achaemenid and Sassanian Empires, the first and last of the Pre-Islamic Persian dynasties. This ancestry begins with a connection of the Persian kings to the Greek mythology according to Plato. I have included these kind of connections between myth and history, the reader may decide if and where such a connection really takes place. Plato 428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. King or Shah Cyrus the Great established the first dynasty of Persia about 550 BC. A special list, “Byzantine Emperors” is inserted (at page 27) after the first part showing the lineage from early Egyptian rulers to Cyrus the Great and to the last king of that dynasty, Artaxerxes II, whose daughter Rodogune became a Queen of Armenia. Their descendants tie into our lineage listed in my books about our lineage from our Byzantine, Russia and Poland. The second begins with King Ardashir I, the 59th great grandfather, reigned during 226-241 and ens with the last one, King Yazdagird III, the 43rd great grandfather, reigned during 632 – 651. He married Maria, a Byzantine Princess, which ties into our Byzantine Ancestry. -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

Puschnigg, Gabrielle 2006 Ceramics of the Merv Oasis; Recycling The

Ceramics of the Merv Oasis: recycling the city Gabriele Puschnigg CERAMICS OF THE MERV OASIS PUBLICATIONS OF THE INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON Director of the Institute: Stephen Sherman Publications Series Editor: Peter J. Ucko The Institute of Archaeology of University College London is one of the oldest, largest and most prestigious archaeology research facilities in the world. Its extensive publications programme includes the best theory, research, pedagogy and reference materials in archaeology and cognate disciplines, through publishing exemplary work of scholars worldwide. Through its publications, the Institute brings together key areas of theoretical and substantive knowledge, improves archaeological practice and brings archaeological findings to the general public, researchers and practitioners. It also publishes staff research projects, site and survey reports, and conference proceedings. The publications programme, formerly developed in-house or in conjunction with UCL Press, is now produced in partnership with Left Coast Press, Inc. The Institute can be accessed online at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology. ENCOUNTERS WITH ANCIENT EGYPT Subseries, Peter J. Ucko, (ed.) Jean-Marcel Humbert and Clifford Price (eds.), Imhotep Today (2003) David Jeffreys (ed.), Views of Ancient Egypt since Napoleon Bonaparte: Imperialism, Colonialism, and Modern Appropriations (2003) Sally MacDonald and Michael Rice (eds.), Consuming Ancient Egypt (2003) Roger Matthews and Cornelia Roemer (eds.), Ancient Perspectives on Egypt (2003) David O'Connor and Andrew Reid (eds.). Ancient Egypt in Africa (2003) John Tait (ed.), 'Never had the like occurred': Egypt's View of its Past (2003) David O'Connor and Stephen Quirke (eds.), Mysterious Lands (2003) Peter Ucko and Timothy Champion (eds.), The Wisdom of Egypt: Changing Visions Through the Ages (2003) Andrew Gardner (ed.), Agency Uncovered: Archaeological Perspectives (2004) Okasha El-Daly, Egyptology, The Missing Millennium: Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writing (2005) Ruth Mace, Clare J.