The Opening Bassoon Solo to the Rite of Spring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky's Renard

Russia ‘Reimagined’: Artistic Hybridism in Stravinsky’s Renard (1915 -1916) © 2005 by Helen Kin Hoi Wong In his Souvenir sur Igor Stravinsky , the Swiss novelist Ramuz recalled his first impression of Stravinsky as a Russian man of possessiveness: What I recognized in you was an appetite and feeling for life, a love of all that is living.. The objects that made you act or react were the most commonplace... While others registered doubt or self-distrust, you immediately burst into joy, and this reaction was followed at once by a kind of act of possession, which made itself visible on your face by the appearance of two rather wicked-looking lines at the corner of your mouth. What you love is yours, and what you love ought to be yours. You throw yourself on your prey - you are in fact a man of prey. 1 Ramuz’s comment perhaps explains what make Stravinsky’s musical style so pluralistic - his desire to exploit native materials and adopt foreign things as if his own. When Stravinsky began working on the Russian libretto of Renard in 1915, he was living in Switzerland in exile, leaving France where he had established his career. As a Russian avant-garde composer of extreme folklorism (as demonstrated in the Firebird , Petrushka and the Rite ), Stravinsky was never on edge in France. His growing friendship with famous French artists such as Vati, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Cocteau and Claudel indicated that he was gradually being perceived as part of the French artistic culture. In fact, this change of perception on Stravinsky was more than socially driven, as his musical language by the end of the War (1918) had clearly transformed to a new type which adhered to the French popular taste (as manifested in L'Histoire du Soldat , Five Easy Pieces and Ragtime ). -

Ballet? Y First the Ballerina Glides Across the Stage, Her Arms M Making Lovely Lines in the Air

My First alle B Album t What is Ballet? Firs The ballerina glides across the stage, her arms My t making lovely lines in the air. A beautiful tune comes from the strings of the large orchestra. She is the Sleeping Beauty: she was put into a allet deep magic sleep by the wicked witch. But she B lbum has now been woken by her handsome prince, A and he dances joyfully with her, athletic and strong. Another time, she is Princess Odette from Swan Lake, and around her the other dancers – swans in white chiffon – weave patterns in time to the music. And yet another time, she is the Sugar Plum Fairy celebrating the joy of Christmas in The Nutcracker. This is ballet, the classical dance that, once seen, is never forgotten. Even though today we have film and video games, ballet is still a powerful vision of beauty and excitement. The dancers use the strength of an athlete, the balance of a gymnast and the sensitivity of a violinist to tell stories through their dancing. Here is some of the best music which has propelled dancers for hundreds of years. 2 Tchaikovsky Swan Lake Stravinsky The Firebird 1 Scene 2:37 3 Scene I. The Firebird’s Dance 1:19 Keyword: Oboe Keyword: Fire Swan Lake is a ballet from Russia about a prince called Siegfried. In the forest he finds A firebird is a brightly coloured magical bird that comes a mysterious lake where swans are swimming, led by a beautiful but sad swan wearing out of the fire. -

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky Source: http://www.8notes.com/biographies/stravinsky.asp ‘Even during his lifetime, Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was a legendary figure. His once revolutionary work were modern classics, and he influenced three generations of composers and other artists. Cultural giants like Picasso and T. S. Eliot were his friends. President John F. Kennedy honored him at a White House dinner in his eightieth year. 'Stavinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia, near St. Petersburg (Leningrad), grew up in a musical atmosphere, and studied with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. He had his first important opportunity in 1909, when the impresario Sergei Diaghilev heard his music. Diaghilev was the director of the Russian Ballet, an extremely influential troupe which employed great painters as well as important dances, choreographers, and composers. Diaghilev first asked Stravinsky to orchestrate some piano pieces by Chopin as ballet music and then, in 1910, commissioned an original ballet, The Firebird, which was immensely successful. A year later (1911), Stravinsky's second ballet, Petrushka, was performed, and Stravinsky was hailed as a modern master. When his third ballet, The Rite of Spring (a savage, brutal portrayal of a prehistoric ritual in which a young girl is sacrificed to the god of Spring.), had its premiere in Paris in 1913, a riot erupted in the audience--spectators were shocked and outraged by its pagan primitivism, harsh dissonance, percussiveness, and pounding rhythms--but it too was recognized as a masterpiece and influenced composers all over the world. 'During World War I, Stravinsky sought refuge in Switzerland; after the armistice, he moved to France, his home until the onset of World War II, when he came to the United States. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

Igor Stravinsky's “Symphony of Psalms” – a Testimony of the Composer's Faith

Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov Series VIII: Performing Arts • Vol. 9 (58) No. 2 - 2016 Igor Stravinsky’s “Symphony of Psalms” – a testimony of the composer’s faith Petruţa-Maria COROIU 1, Alexandra BELIBOU2 Abstract: In the musical landscape of the first half of the 20th century, Igor Stravinsky (1882- 1971) asserted himself as a musician who undermined the normative values of the elements in the musical discourse. His creations were regarded from an analytical perspective in opposition with Arnold Schonberg’s music, the musical critics trying to limit the compositional amendments of the 20th century to the scores of the two composers. We find this view unjust, the musical wealth of the 20th century stemming precisely from the multiple meanings framed within various compositional patterns by the composers which music history placed among the unforgettable ones. Key-words: faith, modernity, psalm, composition, style 1. Preliminary considerations In the musical landscape of the first half of the 20th century, Igor Stravinsky (1882- 1971) asserted himself as a musician who undermined the normative values of the elements in the musical discourse. His creations were regarded from an analytical perspective in opposition with Arnold Schonberg’s music, the musical critics trying to limit the compositional amendments of the 20th century to the scores of the two composers. We find this view unjust, the musical wealth of the 20th century stemming precisely from the multiple meanings framed within various compositional patterns by the composers which music history placed among the unforgettable ones. It is worth noting that Stravinsky and Schonberg “constitute the poles towards gravitate the tendencies of the other composers of the century” (Vlad 1967, 7) (our translation). -

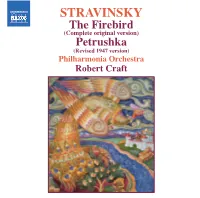

STRAVINSKY the Firebird

557500 bk Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 8 Philharmonia Orchestra STRAVINSKY The Philharmonia Orchestra, continuing under the renowned German maestro Christoph von Dohnanyi as Principal Conductor, has consolidated its central position in British musical life, not only in London, where it is Resident Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall, but also through regional residencies in Bedford, Leicester and Basingstoke, The Firebird and more recently Bristol. In recent seasons the orchestra has not only won several major awards but also received (Complete original version) unanimous critical acclaim for its innovative programming policy and commitment to new music. Established in 1945 primarily for recordings, the Philharmonia Orchestra went on to attract some of this century’s greatest conductors, such as Furtwängler, Richard Strauss, Toscanini, Cantelli and von Karajan. Otto Klemperer was the Petrushka first of many outstanding Principal Conductors throughout the orchestra’s history, including Maazel, Muti, (Revised 1947 version) Sinopoli, Giulini, Davis, Ashkenazy and Salonen. As the world’s most recorded symphony orchestra with well over a thousand releases to its credit, the Philharmonia Orchestra also plays a prominent rôle as one of the United Kingdom’s most energetic musical ambassadors, touring extensively in addition to prestigious residencies in Paris, Philharmonia Orchestra Athens and New York. The Philharmonia Orchestra’s unparalleled international reputation continues to attract the cream of Europe’s talented young players to its ranks. This, combined with its brilliant roster of conductors and Robert Craft soloists, and the unique warmth of sound and vitality it brings to a vast range of repertoire, ensures performances of outstanding calibre greeted by the highest critical praise. -

A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye's À La Manière De Stravinsky Pour Trombone Et Piano

A COMPARISON OF RHYTHM, ARTICULATION, AND HARMONY IN JEAN- MICHEL DEFAYE’S À LA MANIÈRE DE STRAVINSKY POUR TROMBONE ET PIANO TO COM MON COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES OF IGOR STRAVINSKY Dustin Kyle Mullins, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Tony Baker, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Minor Professor John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Mullins, Dustin Kyle. A Comparison of Rhythm, Articulation, and Harmony in Jean-Michel Defaye’s À la Manière de Stravinsky pour Trombone et Piano to Common Compositional Strategies of Igor Stravinsky. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2014, 45 pp., 2 tables, 27 examples, references, 28 titles. À la Manière de Stravinsky is one piece in a series of works composed by Jean- Michel Defaye that written emulating the compositional styles of significant composers of the past. This dissertation compares Defaye’s work to common compositional practices of Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). There is currently limited study of Defaye’s set of À la Manière pieces and their imitative characteristics. The first section of this dissertation presents the significance of the project, current literature, and methods of examination. The next section provides critical information on Jean-Michel Defaye and Igor Stravinsky. The following three chapters contain a compositional comparison of À la Manière de Stravinsky to Stravinsky’s use of rhythm, articulation, and harmony. The final section draws a conclusion of the piece’s significance in the solo trombone repertoire. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5. -

Notes on the Oedipus Works

Notes on the Oedipus Works Matthew Aucoin The Orphic Moment a dramatic cantata for high voice (countertenor or mezzo-soprano), solo violin, and chamber ensemble (15 players) The story of Orpheus is music’s founding myth, its primal self-justification and self-glorification. On Orpheus’s wedding day, his wife, Eurydice, is fatally bitten by a poisonous snake. Orpheus audaciously storms the gates of Hell to plead his case, in song, to Hades and his infernal gang. The guardians of death melt at his music’s touch. They grant Eurydice a second chance at life: she may follow Orpheus back to Earth, on the one condition that he not turn to look at her until they’re above ground. Orpheus can’t resist his urge to glance back; he turns, and Eurydice vanishes. The Orpheus myth is typically understood as a tragedy of human impatience: even when a loved one’s life is at stake, the best, most heroic intentions are helpless to resist a sudden instinctive impulse. But that’s not my understanding of the story. Orpheus, after all, is the ultimate aesthete: he’s the world’s greatest singer, and he knows that heartbreak and loss are music’s favorite subjects. In most operas based on the Orpheus story – and there are many – the action typically runs as follows: Orpheus loses Eurydice; he laments her loss gorgeously and extravagantly; he descends to the underworld; he gorgeously and extravagantly begs to get Eurydice back; he is granted her again and promptly loses her again; he laments even more gorgeously and extravagantly than before. -

CHAN 6654 BOOK.Qxd 22/5/07 4:18 Pm Page 2

CHAN 6654 Cover.qxd 22/5/07 4:17 pm Page 1 CHAN 6654(5) CHAN 6654 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 4:18 pm Page 2 Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) COMPACT DISC TWO TT 79:14 Le Chant du Rossignol (1917) 20:56 COMPACT DISC ONE TT 76:46 1 Presto – 2:20 Symphony in E flat, Op. 1 (1905–07) 34:12 2 Marche chinoise 3:32 1 I Allegro moderato 9:42 3 Le Chant du Rossignol – 3:36 2 II Scherzo. Allegretto 6:03 4 Le Jeu du Rossignol mécanique 11:28 3 III Largo 9:42 Stephen Jeandheur trumpet solo 4 IV Finale. Allegro molto 7:38 Symphony in Three Movements (1942–45)* 21:19 5 Violin Concerto (1931) 21:54 I = 160 9:09 5 I Toccata 5:28 6 II Andante – Più mosso – Tempo I 6:08 6 II Aria I 4:58 7 III Con moto 5:58 7 III Aria II 5:27 8 IV Capriccio 5:50 Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra (1949)* 16:56 Lydia Mordkovitch violin 8 I Presto 6:40 9 II Andante rapsodico 5:05 Symphony of Psalms (1930) 21:52 10 III Allegro capriccioso ma sempre giusto 5:11 9 I Exaudi orationem meam, Domine 3:02 Geoffrey Tozer piano 10 II Expectans expectavi Dominum 7:02 11 III Alleluja, laudate Dominum 11:15 Concerto for Piano and Wind Chœur de Chambre Romand Instruments (1950) 19:31 Chœur Pro Arte de Lausanne 11 I Largo – Allegro – Più mosso – Maestoso Société chorale du Brassus (Largo del principo) 7:14 André Charlet chorus master 12 II Largo – Più mosso – Doppia valore – Tempo primo 7:21 13 III Allegro – Agitato – Lento – Strigendo 4:50 Boris Berman piano 2 3 CHAN 6654 BOOK.qxd 22/5/07 4:18 pm Page 4 COMPACT DISC THREE TT 66:36 Tableau II 24:25 Petrushka (1911) 33:03 16 Apollo’s Variation 2:48 Tableau I: The Shrovetide Fair 9:31 17 Pas d’action 4:17 1 The Crowds 5:03 18 Calliope’s Variation. -

Stravinsky’S Most Popular AXOS Work, the Firebird

557500 rr Firebird US 14/01/2005 12:19pm Page 1 N N AXOS This is the first recording of the Complete Original Version of Stravinsky’s most popular AXOS work, The Firebird. Among the many differences between the present recording and its predecessors is the restoration of two long, valveless trumpets on stage, each playing a single note standing out above the entire orchestra. This is a thrilling effect in all likelihood heard for the first time since 1910 on this recording. Compared to the lush DDD orchestra of The Firebird, the sonorities of Petrushka may seem brittle but harmonically, STRAVINSKY: rhythmically, and instrumentally the work is innovative on every page, a drama of great 8.557500 STRAVINSKY: power and originality. Playing Time Igor WORLD PREMIERE 78:53 RECORDING STRAVINSKY (1882-1971) The Firebird (1910)* 44:52 Petrushka 34:01 Ballet in Two Scenes (1911, Revised 1947) The Firebird • Petrushka The Firebird The Firebird • Petrushka The Firebird 1 Introduction 2:34 A Burlesque in Four Scenes 2-¡ Scene I 39:22 £-∞ First Tableau ™ Scene II 2:55 § Second Tableau ¶-ª Third Tableau www.naxos.com Made in Canada Booklet notes in English Naxos Rights International Ltd. h 1997, 1998 & º-· Fourth Tableau Philharmonia Orchestra • Robert Craft Recorded at Abbey Road Studios, London, England, on 27th & 29th November 1996 (Firebird) and 31st January & 1st February 1997 (Petrushka) g Producer: Gregory K. Squires • Engineers: Michael Sheady (Firebird) and Alex Marcou (Petrushka) 2005 Editors: Richard Price (Firebird) and Wayne Hileman (Petrushka) • Booklet Notes: Robert Craft Publishers: Schott Music International (Firebird) Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd.