Analysis of Impacts to K-12 Public Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011-13 W Isconsin State B Udget

Comparative Summary of Budget Recommendations 2011 2011 Act 32 - Budget State Wisconsin 13 (Including Budget Adjustment Acts 10, 13, and 27) Volume I Legislative Fiscal Bureau August, 2011 2011-13 WISCONSIN STATE BUDGET Comparative Summary of Budget Provisions Enacted as 2011 Act 32 (Including Budget Adjustment Acts 10, 13, and 27) Volume I LEGISLATIVE FISCAL BUREAU ONE EAST MAIN, SUITE 301 MADISON, WISCONSIN LEGISLATIVE FISCAL BUREAU Administrative/Clerical Health Services and Insurance Bob Lang, Director Charles Morgan, Program Supervisor Vicki Holten, Administrative Assistant Sam Austin Liz Eck Grant Cummings Sandy Swain Eric Peck Education and Building Program Natural Resources and Commerce Dave Loppnow, Program Supervisor Daryl Hinz, Program Supervisor Russ Kava Kendra Bonderud Layla Merrifield Paul Ferguson Emily Pope Erin Probst Al Runde Ron Shanovich General Government and Justice Tax Policy, Children and Families, and Workforce Development Jere Bauer, Program Supervisor Chris Carmichael Rob Reinhardt, Program Supervisor Paul Onsager Sean Moran Darin Renner Rick Olin Art Zimmerman Ron Shanovich Sandy Swain Kim Swissdorf Transportation and Property Tax Relief Fred Ammerman, Program Supervisor Jon Dyck Rick Olin Al Runde INTRODUCTION This two-volume document, prepared by Wisconsin's Legislative Fiscal Bureau, is the final edition of the cumulative summary of executive and legislative action on the 2011-13 Wisconsin state biennial budget. The budget was signed by the Governor as 2011 Wisconsin Act 32 on June 26, and published on June 30, 2011. This document describes each of the provisions of Act 32, including all fiscal and policy modifications recommended by the Governor, Joint Committee on Finance, and Legislature. The document is organized into eight sections, the first of which contains a Table of Contents, History of the 2011-13 Budget, Brief Chronology of the 2011-13 Budget, Key to Abbreviations, and a User's Guide. -

Medium-Run Consequences of Wisconsin's Act 10: Teacher

MEDIUM-RUN CONSEQUENCES OF WISCONSIN'S ACT 10: TEACHER PAY AND EMPLOYMENT∗ Rebecca Jorgensen† Charles C. Moul‡ July 25, 2020 Abstract Wisconsin's Act 10 in 2011 gutted collective bargaining rights for public school teachers and mandated benefits cuts for most districts. We use various cross-state methods on school-district data from school years 2002-03 to 2015-16 to examine the act's immediate and medium-run net impacts on compensation and employment. We find that Act 10 coincided with ongoing significant benefit declines beyond the immediate benefit cuts. Controlling for funding level and composition reveals that Wisconsin school districts, unlike their control counterparts, have seen the number of teachers per student rise in the years since Act 10. Keywords: Educational finance, collective bargaining, public policy JEL Classification: H75, J58, I22 I Introduction Few state issues of the past decade inflamed popular sentiment as much as public employee union reform, and the collective bargaining rights of teachers' unions in particular were shoved into the limelight. In early 2011 Wisconsin took center stage with Act 10, a law that effectively man- dated steep cuts in district pension and health care contributions, virtually eliminated collective bargaining, and prohibited forced payment of dues for members. Given the concurrent changes to school funding levels and composition, the predicted impacts on Wisconsin schools were highly uncertain, with forecasts ranging from the apocalyptic to the near-miraculous.1 ∗This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-1845298. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. -

1 Julaine K. Appling, Jo Egelhoff, Jaren E. Hiller

STATE OF WISCONSIN CIRCUIT COURT DANE COUNTY BRANCH 11 JULAINE K. APPLING, JO EGELHOFF, JAREN E. HILLER, RICHARD KESSENICH, and EDMUND L. WEBSTER, Plaintiffs, DECISION AND ORDER vs. JAMES E. DOYLE, Case No. 10-CV-4434 KAREN TIMBERLAKE, and JOHN KIESOW, Defendants, and FAIR WISCONSIN, INC., GLENN CARLSON & MICHAEL CHILDERS, CRYSTAL HYSLOP & JANICE CZYSCON, KATHY FLORES & ANN KENDZIERSKI, DAVID KOPITZKE & PAUL KLAWITER, and CHAD WEGE & ANDREW WEGE, Intervening Defendants. This is a Decision and Order regarding Intervening Defendants’ and Plaintiffs’ cross- motions for summary judgment. For the reasons discussed below, Intervening Defendants’ motion for summary judgment is GRANTED and Plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment is DENIED. 1 BACKGROUND I. Facts On August 1, 2009, Wis. Stats. Chapter 770, which created the Domestic Partner Registry for same-sex couples, went into effect. Claiming to be injured because they are taxpayers, Plaintiffs challenge Chapter 770 as unconstitutional under Article VII, Sec. 13 of the Wisconsin Constitution (hereinafter referred to as the “Marriage Amendment”), alleging that the status created by Chapter 770, that is, the status of “domestic partnership,” is “substantially similar to that of marriage.” II. Parties All Plaintiffs are adult residents and taxpayers of the State of Wisconsin. (Compl. ¶¶ 3- 4). Prior to or during the legislative approval process and ratification campaign the Marriage Amendment, Plaintiff Julaine K. Appling was the President of Wisconsin Family Action (“WFA”), a Wisconsin not-for-profit organization engaged in public education and advocacy supporting approval and ratification of the Amendment. (Id.; Appling Aff. ¶¶ 1-2, March 8, 2011). Appling also served as chief executive officer of the Family Research Institute of Wisconsin (“FRI”) (n/k/a “Wisconsin Family Council”), a Wisconsin not-for-profit organization engaged in public education regarding family and social issues. -

Journal of the American Society of Legislative Clerks and Secretaries

Journal of the American Society of Legislative Clerks and Secretaries Volume 22 Fall 2017 Information for Authors .............................................................................................. 2 A Note From the Editors ............................................................................................. 3 Richard A. Champagne Organizing the Wisconsin State Assembly ................................................................. 4 Eric S. Silvia Legislative Immunity .................................................................................................. 15 Professional Journal Index .......................................................................................... 63 Fall 2017 ©Journal of the American Society of Legislative Clerks and Secretaries Page 1 Journal of the American Society of Legislative Clerks and Secretaries 2016-2017 Committee Chair: Bernadette McNulty, CA Senate Chief Assistant Secretary of the Senate Vice Chair: Ann Krekelberg, AK Senate Supervisor, Senate Records Vice Chair: Tammy Wright, NH Senate Clerk of the Senate Members Tamitha M. Jackson (AR) Martha L. Jarrow (AR) Jacquelyn Delight (CA) Brian Ebbert (CA) Brad Westmoreland (CA) Heshani Wijemanne (CA) Mary Ann Krol (KY) Steven M. Tilley (LA) Gail Romanowski (MN) Adriane Crouse (MO) Joy Engelby (MO) Jason Hataway (NV) Mandi McGowan (OR) Ginny Edwards (VA) Geneva Tulasz (VA) Laura Bell (WA) Gary Holt (WA) Sarah E. Burhop (WI) Erin Gillitzer (WI) Wendy Harding (WY) Fall 2017 ©Journal of the American Society of Legislative -

The Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, 3 U.C

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 3 Issue 3 Foxes, Henhouses, and Commissions: Assessing Article 7 the Nonpartisan Model in Election Administration, Redistricting, and Campaign Finance 8-2013 America’s Top Model: The iW sconsin Government Accountability Board Daniel P. Tokaji Ohio State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Election Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel P. Tokaji, America’s Top Model: The Wisconsin Government Accountability Board, 3 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 575 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol3/iss3/7 This Article and Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. America’s Top Model: The Wisconsin Government Accountability Board Daniel P. Tokaji* Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 575 I. The Wisconsin Model ................................................................................................. 577 II. The Experience of Wisconsin’s Government Accountability Board ................ 586 A. Voter Registration ......................................................................................... 586 B. Early and Absentee Voting ......................................................................... 591 C. Voter Identification -

Local Government Employee Issues

Municipalitythe A publication of the League of Wisconsin Municipalities February 2015, Volume 110, Number 2 Local Government Employee Issues In this issue: Protective Services Collective Bargaining Municipal Grievance Policy WI Municipalities’ Employment Statistics Municipalitythe A publication of the League of Wisconsin Municipalities February 2015 Volume 110, Number 2 Departments Contents From the Protective Service Executive Dir. 41 Collective Bargaining in a Post-Act 10 and Act 32 World 42 Legal FAQs 58 Municipal Grievance Policy Under League Acts 10 and 32 52 Calendar 67 Wisconsin Municipalities’ Web Employee Statistics 61 Siting 67 We’re Gearing Up Legal Join the Captions 69 League’s Lobby Team 62 Local Officials Street Talk In the News 70 One Hundred Years Ago 65 Cover photo: Village of Work Place Wellness Programs Waunakee Fire Station No. 1 by Jean Staral. How Well Do You Measure Up 71 the Municipality February 2015 39 From the Executive Director Don’t Forget Leadership This month’s issue of the Municipality You’re a manager and you need to hawks soar but can’t run worth is focused on important topics for the understand how to use the tools of a darn.) people who manage local govern- management. But you must also be ments. In the last few years, a lot has a leader. You are the one who must There are lots of ways to define the changed when it comes to manag- have the vision of where your com- skills needed for leadership, but I ing local government employees, munity is and where it should be, or think these four work pretty well. -

Conservative-Digest

Free Sample Copy Issue: 8 Cost: $1.25 of Conservative Issues and Ideas Taxpayers taken for a ride, a ride that is now ending By Sen. Alberta Darling (R-8th District) permanent maintenance facility for 20 years vs. and Rep. Robin Vos (R-63rd District) the cost of running the current Amtrak trains. The difference made last week's decisions an This past session, we spent a lot of time fix- easy one for Wisconsin taxpayers. ing the mess former Gov. Jim Doyle and the The nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau Democrats made when they were in power. From estimated that Talgo trains would cost taxpayers filling a $3.6 billion deficit to repaying the $10 million more each year for the next 20 years. Injured Victims Compensation Fund that he raid- We didn't believe it was wise to throw $200 mil- ed, we've made it our goal to protect taxpayers lion taxpayer dollars at a bad project. from the bad decisions made in years past. As the The state would be bound by contract to have chairs of the budget-writing Joint Committee on a more frequent maintenance schedule than Finance, it is our job to be responsible stewards Amtrak, instantly inflating the cost of operations with the generous money taxpayers provide the by 3%. These new Talgo trains have to be serv- state. iced every other day. The current Amtrak trains The no-bid Talgo Inc. contract was astonish- are maintained on a set schedule and on an as- ingly irresponsible, even by Doyle and the needed basis, similar to how you maintain your Democrats' fiscal standards. -

ALEC Exposed in Wisconsin: the Hijacking of a State Executive Summary

ALEC EXPOSED [WISCONSIN] THE HIJACKING OF A STATE A REPORT FROM THE CENTER FOR MEDIA! AND DEMOCRACY © 2012 Center for Media and Democracy. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by information exchange and retrieval system, without permission from the authors. CENTER FOR MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY ALECexposed.org!|!PRWatch.org | SourceWatch.org!| BanksterUSA.org FoodRightsNetwork.org!|!AtrazineExposed.org 520 University Avenue, Suite 260 Madison, WI 53703 | (608) 260-9713 (This publication is available on the internet at ALECexposed.org) Acknowledgements: This report is authored by Brendan Fischer. We would also like to acknowledge everyone at CMD who helped with research, writing and other support for this project – Lisa Graves, Mary Bottari, Rebekah Wilce, Sara Jerving, Harriet Rowan, Friday Thorn, Sari Williams, Patricia Barden, Nikolina Lazic, Beau Hodai, Will Dooling, Emily Osborne, and Alex Oberley. We would also like to acknowledge the work of our friends and colleagues at Common Cause, Color of Change, People for the American Way, and ProgressNow/the Institute for One Wisconsin. ! Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction 1 II. ALEC in Wisconsin 3 Chart 1: Wisconsin Legislators and ALEC Task Force Assignments 12 III. ALEC Meetings: Corporate-Funded Events and Scholarships 14 Chart 2: The Wisconsin ALEC "Scholarship" Fund 16 IV. Examples of ALEC Provisions in the Wisconsin 2011-2012 Session 19 AB 69: -

Wisconsin County Official's Handbook

6th Edition Handbook.indd 1 5/30/18 1:54 PM This handbook sets forth general information on the topics addressed and does not constitute legal advice. You should contact your county’s legal counsel for specific advice. 2018 Published by Wisconsin Counties Association 22 E. Mifflin St., Suite 900 Madison, WI 53703 1.866.404.2700 www.wicounties.org 6th Edition Handbook.indd 2-3 5/30/18 1:54 PM CHAPTERWELCOME HEAD 6th Edition The Wisconsin County Official’s Handbook: Empowering County Officials through Education Mark D. O’Connell, Executive Director, Wisconsin Counties Association s a county official, you are faced daily with the daunting task of understanding a myriad of county issues and implementing complex programs and services. This must be done in such a way as to best meet the needs of your constituents, while holding the line on pre- Acious tax dollars. Government at any level is a fluid entity and with constantly changing issues and emerging trends, this is not an easy task. In your hands is the 6th edition of the Wisconsin County Official’s Handbook, the most comprehensive document to date on county operations. It was produced by the Wisconsin Counties Association (WCA) staff in response to members’ ongoing requests for additional educational materials. The handbook is comprised of a collection of information covering topics that county officials handle on a regular basis. From an in-depth review of parliamentary procedures to personnel practices to budgeting, this document brings together all areas of county operations in one centralized place. It is our intention to keep the information provided within these pages current and make any nec- essary revisions to the content. -

OFFICIAL PROCEEDINGS – 2011 Board Of

February 3, 2011 OFFICIAL PROCEEDINGS – 2011 Board of Supervisors Courthouse, Milwaukee, Wisconsin Lee Holloway Chairman Michael Mayo, Sr. First Vice Chairman Peggy West Second Vice Chairman Members of the Board District Phone 1st THEO LIPSCOMB ………….…………….………………….. 278-4280 2nd NIKIYA HARRIS….………………………………………… 278-4278 3rd GERRY P. BRODERICK …..………………………………… 278-4237 4th MARINA DIMITRIJEVIC ..………………………….………. 278-4232 5th LEE HOLLOWAY…………………………………….………. 278-4261 6th JOSEPH RICE………………………………….……………… 278-4243 7th MICHAEL MAYO, SR. ……………..…………..…………….. 278-4241 8th PATRICIA JURSIK …………………………….…………….. 278-4231 9th PAUL M. CESARZ …………………………………………… 278-4267 10th VACANT………………… ……………………………………. 278-4265 11th MARK A. BORKOWSKI ………………………….…………. 278-4253 12th PEGGY WEST ………………………………………………… 278-4269 13th WILLIE JOHNSON, JR. ……………………………………… 278-4233 14th VACANT………………….. …………………………………… 278-4252 15th LYNNE DE BRUIN ……………………………………………. 278-4263 16th JOHN F. WEISHAN, JR. ……………………………………… 278-4255 17th JOSEPH SANFELIPPO ………………………………………. 278-4247 18th JOHNNY L. THOMAS ……………………………………….. 278-4259 19th JAMES J. SCHMITT …………………………………………. 278-4273 JOSEPH J. CZARNEZKI County Clerk ANNUAL MEETING (CONTINUED) February 3, 2011 1 February 3, 2011 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Thursday, February 3, 2011, 9:35 a.m. Supervisor Mayo in the Chair. PRESENT: Borkowski, Broderick, Cesarz, De Bruin, Dimitrijevic, Harris, Johnson, Jursik, Lipscomb, Rice, Sanfelippo, Schmitt, Thomas, Weishan, West and the Chairman – 16 ABSENT: – 0 EXCUSED: Holloway – 1 Chairman Mayo opened the meeting with the recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance and a moment of silence. PRESENTATION BY SUPERVISORS Supervisors Harris, Johnson and Thomas offered presentations. APPROVAL OF THE JOURNAL OF PROCEEDINGS On a motion by Supervisor West, the Journal of Proceedings of December 16, 2010 WAS APPROVED by a voice vote. REPORTS OF COUNTY OFFICERS Confirmation of appointments: File No. 11-88 From the County Executive, appointing Mr. -

Legislative Fiscal Bureau (LFB) on February 9, 2012

OFFICIAL STATEMENT New Issue This Official Statement provides information about the Certificates. Some of the information appears on this cover page for ready reference. To make an informed investment decision, a prospective investor should read the entire Official Statement. $26,810,000 MASTER LEASE CERTIFICATES OF PARTICIPATION OF 2012, SERIES A Evidencing Proportionate Interests of the Owners Thereof in Certain Lease Payments to be Made by the STATE OF WISCONSIN Acting by and through the Department of Administration Dated: Delivery Date Maturities: March 1 and September 1, as shown on inside front cover Ratings AA– Fitch Ratings Aa3 Moody’s Investors Service, Inc. AA– Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Tax Exemption Interest on the Certificates is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes and is not a specific item of tax preference for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax imposed on all taxpayers–See pages 10-11. Interest on the Certificates is not exempt from current State of Wisconsin income and franchise taxes–See page 11. Redemption Optional—The Certificates are not callable prior to maturity. Mandatory—Master lease certificates of participation of all series, including the Certificates, are subject to mandatory redemption at par upon an Event of Default under the Master Indenture, which includes Nonappropriation or an Event of Default under the Master Lease or any Lease Schedule–See page 3. Security Certificates evidence proportionate interests in certain Lease Payments under the State’s Master Lease Program. The Master Lease requires the State to make Lease Payments from any source of legally available funds, subject to annual appropriation. -

Become Even More Effective with Wasb Boarddocs Pro!

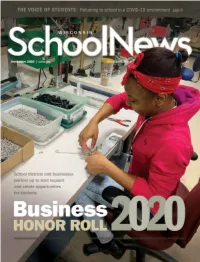

WASB_boarddocspro_8.25”x10.75.pdf 1 02/04/2019 21:30 F oc u BECOME EVEN MORE EFFECTIVE WITH sed. Accou WASB BOARDDOCS PRO! Take your meeting management to the next level with the most robust board management tool available. Designed to fit the needs of school Some features include: Advanced document workflow with electronic approvals from an unlimited number of document submitter C Integrated strategic plan and goal tracking n M Automatic generation of minutes and live meeting control panel Y for all board actions t CM ab MY Integrated private annotations for executive users CY CMY Much more! K l e. D a t a-S a vvy. Learn more! BoardDocs.com (800) 407-0141 December 2020 | Volume 74 Number 15 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WISCONSIN ASSOCIATION OF SCHOOL BOARDS, INC. John H. Ashley Executive Editor Sheri Krause Editor Director of Communications n REGIONAL OFFICES n 122 W. Washington Avenue Madison, WI 53703 Phone: 608-257-2622 Fax: 608-257-8386 132 W. Main Street Winneconne, WI 54986 Phone: 920-582-4443 Fax: 920-582-9951 n ADVERTISING n 608-556-9009 • [email protected] n WASB OFFICERS n NORTHLAND ELECTRICAL SERVICES DONATED ALTERNATIVE SEATING TO THE NEW LONDON SCHOOL DISTRICT John H. Ashley Executive Director Bill Yingst, Sr. Business Honor Roll 2020 We Are Listening! Durand-Arkansaw, Region 4 4 School districts and businesses 16 Lynn Armitage President partner up to lend support and RERIC partners with Sue Todey create opportunities for students. rural Wisconsin. Sevastopol, Region 3 1st Vice President Barbara Herzog The Voice of Students Your Superintendent Oshkosh, Region 7 8 Sharon Belton, Ph.D.