The Wisconsin Public-Sector Labor Dispute of 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011-13 W Isconsin State B Udget

Comparative Summary of Budget Recommendations 2011 2011 Act 32 - Budget State Wisconsin 13 (Including Budget Adjustment Acts 10, 13, and 27) Volume I Legislative Fiscal Bureau August, 2011 2011-13 WISCONSIN STATE BUDGET Comparative Summary of Budget Provisions Enacted as 2011 Act 32 (Including Budget Adjustment Acts 10, 13, and 27) Volume I LEGISLATIVE FISCAL BUREAU ONE EAST MAIN, SUITE 301 MADISON, WISCONSIN LEGISLATIVE FISCAL BUREAU Administrative/Clerical Health Services and Insurance Bob Lang, Director Charles Morgan, Program Supervisor Vicki Holten, Administrative Assistant Sam Austin Liz Eck Grant Cummings Sandy Swain Eric Peck Education and Building Program Natural Resources and Commerce Dave Loppnow, Program Supervisor Daryl Hinz, Program Supervisor Russ Kava Kendra Bonderud Layla Merrifield Paul Ferguson Emily Pope Erin Probst Al Runde Ron Shanovich General Government and Justice Tax Policy, Children and Families, and Workforce Development Jere Bauer, Program Supervisor Chris Carmichael Rob Reinhardt, Program Supervisor Paul Onsager Sean Moran Darin Renner Rick Olin Art Zimmerman Ron Shanovich Sandy Swain Kim Swissdorf Transportation and Property Tax Relief Fred Ammerman, Program Supervisor Jon Dyck Rick Olin Al Runde INTRODUCTION This two-volume document, prepared by Wisconsin's Legislative Fiscal Bureau, is the final edition of the cumulative summary of executive and legislative action on the 2011-13 Wisconsin state biennial budget. The budget was signed by the Governor as 2011 Wisconsin Act 32 on June 26, and published on June 30, 2011. This document describes each of the provisions of Act 32, including all fiscal and policy modifications recommended by the Governor, Joint Committee on Finance, and Legislature. The document is organized into eight sections, the first of which contains a Table of Contents, History of the 2011-13 Budget, Brief Chronology of the 2011-13 Budget, Key to Abbreviations, and a User's Guide. -

July 3, 2011 Transcript

© 2011, CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. PLEASE CREDIT ANY QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FROM THIS CBS TELEVISION PROGRAM TO "CBS NEWS' FACE THE NATION." July 3, 2011 Transcript GUESTS: GOV. DEVAL PATRICK, D-Mass. GOV. JOHN KASICH, R-Ohio GOV. SCOTT WALKER, R-Wis. MAYOR ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA, D-Los Angeles MODERATOR/ PANELIST: Bob Schieffer, CBS News Political Analyst This is a rush transcript provided for the information and convenience of the press. Accuracy is not guaranteed. In case of doubt, please check with FACE THE NATION - CBS NEWS (202) 457-4481 TRANSCRIPT BOB SCHIEFFER: Today on FACE THE NATION, Washington and how it looks from outside the Beltway. On this July 4th weekend, Washington remains in gridlock. So we’re checking in with four elected officials from around the country--Massachusetts Democratic Governor Deval Patrick, Wisconsin’s Republican Governor Scott Walker, Ohio’s Republican Governor John Kasich, and Los Angeles Democratic Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. What is the impact with the Washington impasse in their states? What will be the impact out in the country if the President and Congress are unable to reach a deal to raise the debt limit? It’s all next on FACE THE NATION. ANNOUNCER: FACE THE NATION with CBS News chief Washington correspondent Bob Schieffer. And now from Washington, Bob Schieffer. BOB SCHIEFFER: And, good morning again. Welcome to FACE THE NATION on this Fourth of July weekend. Governor Patrick is in Rockport, Massachusetts; Ohio Governor John Kasich is in Richmond, Massachusetts; Wisconsin Republican Scott Walker joins us from his state capital in Madison; and Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa is out at the Aspen Ideas Festival in Aspen, Colorado. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1857

March 14, 2019 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1857 for all of Stew’s colleagues, that level Happy trails, buddy. not your typical vote on an appropria- of good cheer and concern for others f tions or authorization bill. It doesn’t really has been typical for a dozen concern a nomination or an appoint- RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME years. ment. This will be a vote about the That is why his departure has trig- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under very nature of our Constitution, the gered an avalanche of tributes from the previous order, leadership time is separation of powers, and how this gov- people all over Washington and beyond, reserved. ernment functions henceforth. people—many of them junior people— f The Framers gave Congress the whom he wrote back with advice, met power of the purse in article I of the for coffee, shared some wisdom; this CONCLUSION OF MORNING Constitution. It is probably our great- sprawling family tree of men and BUSINESS est power. Now the President is claim- women who all feel that, one way or The PRESIDING OFFICER. Morning ing that power for himself under a another, they owe a significant part of business is closed. guise of an emergency declaration to their success and careers to him. On f get around a Congress that repeatedly that note, I have to say I know exactly RELATING TO A NATIONAL EMER- would not authorize his demand for a how they feel. So today I have to say goodbye to an GENCY DECLARED BY THE border wall. all-star staff leader who took his job PRESIDENT ON FEBRUARY 15, The President has not justified the about as seriously as anybody you will 2019 emergency declaration. -

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Inprez: an Epic, Bizarre Primary Coda in the Assassina- Trump Victory Secures GOP Tion of President Nomination; Sanders’ Upset Kennedy

V21, 35 Thursday, May 5, 2016 INPrez: An epic, bizarre primary coda in the assassina- Trump victory secures GOP tion of President nomination; Sanders’ upset Kennedy. It came at a time when of Clinton prolongs the slog Republicans took a second, long look By BRIAN A. HOWEY at Trump, hoping INDIANAPOLIS – When the dust to see a future settled on one of the most bizarre political president. Instead, sequences in modern Indiana history, Hoo- they got a tabloid sier Republican voters had mostly settled the reality star on the Republican presidential race for Donald Trump verge of a land- while prolonging the primary slog for Hillary slide victory who Clinton with Bernie didn’t know when Sanders’ 53-47% vic- to let up. tory. On the The Indiana Democratic side, primary ended on a voters witnessed frenzied week-long a sprawling Bernie pace as four candi- Sanders rally at dates and an ex-pres- Bobby Knight’s endorsement of Donald Trump became a the foot of the ident courted Hoosiers at more than 50 rallies decisive component of the Manhattan billionaire’s landslide Soldiers & Sailors and retail stops. In the final crescendo, this win over Ted Cruz in the Indiana primary that helped clear Monument and epic drama became surreal as Donald Trump the field on Wednesday. (HPI Photo by Mark Curry) below the corpo- used a National Enquirer article to allege that Ted Cruz’s father was involved with Lee Harvey Oswald Continued on page 4 Pence on Cruz control By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – For Gov. Mike Pence, the presi- dential maelstrom that roared through the state has left him, at least temporarily, twisting, twisting, twisting in the political winds. -

Medium-Run Consequences of Wisconsin's Act 10: Teacher

MEDIUM-RUN CONSEQUENCES OF WISCONSIN'S ACT 10: TEACHER PAY AND EMPLOYMENT∗ Rebecca Jorgensen† Charles C. Moul‡ July 25, 2020 Abstract Wisconsin's Act 10 in 2011 gutted collective bargaining rights for public school teachers and mandated benefits cuts for most districts. We use various cross-state methods on school-district data from school years 2002-03 to 2015-16 to examine the act's immediate and medium-run net impacts on compensation and employment. We find that Act 10 coincided with ongoing significant benefit declines beyond the immediate benefit cuts. Controlling for funding level and composition reveals that Wisconsin school districts, unlike their control counterparts, have seen the number of teachers per student rise in the years since Act 10. Keywords: Educational finance, collective bargaining, public policy JEL Classification: H75, J58, I22 I Introduction Few state issues of the past decade inflamed popular sentiment as much as public employee union reform, and the collective bargaining rights of teachers' unions in particular were shoved into the limelight. In early 2011 Wisconsin took center stage with Act 10, a law that effectively man- dated steep cuts in district pension and health care contributions, virtually eliminated collective bargaining, and prohibited forced payment of dues for members. Given the concurrent changes to school funding levels and composition, the predicted impacts on Wisconsin schools were highly uncertain, with forecasts ranging from the apocalyptic to the near-miraculous.1 ∗This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-1845298. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. -

Lucas County Board of Elections Election Results for Candidates 2010 to Present

Lucas County Board of Elections Election Results For Candidates 2010 to Present GENERAL ELECTION – NOVEMBER 3, 2015 CERTIFIED NOVEMBER 20, 2015 Page 1. Total Voters: 114,294 39.77% Total Registered: 287,382 Total Precincts: 352 (A.V.B. rolled with proper precinct) Toledo Municipal Court Judge (Full term commencing 01/01/2016) Bill Connelly 42,481 Toledo City Mayor Paula Hicks-Hudson 23,087 Michael P. Bell 11,228 17.33% Carty Finkbeiner 10,276 15.86% Sandy Drabik Collins 9,432 14.55% Sandy Spang 7,028 10.85% Mike Ferner 3,208 4.95% Opal Covey 544 0.84% Toledo City Council-at-Large Cecelia M. Adams 35,236 100.00% Toledo City Council-District 1 Tyrone Riley 6,333 72.20% Jennifer L. Scott 2,438 27.80% Toledo City Council-District 2 Matthew A. Cherry 8,350 70.02% Drew D. Blazsik 3,575 29.98% *= most votes Toledo City Council-District 3 Peter Ujvagi 3,258 52.87% Glen Cook 2,904 47.13% Toledo City Council-District 4 Yvonne Harper 4,777 73.58% Peggy Brown-Morehead 1,715 26.42% Toledo City Council-District 5 Tom Waniewski 9,555 100.00% Toledo City Council-District 6 Lindsay M. Webb 7,289 69.80% Bill Delaney 3,154 30.20% Maumee City Mayor Richard H. Carr 3,308 100.00% Maumee City Council-Unexpired Term Timothy L. Pauken 2,581 64.28% Dyana Davis 1,434 35.72% Maumee City Council-Full Term (elect 3) Daniel G. Hazard 2,409 28.06% John P. -

JOHN WEAVER – Chief Strategist Overview

SUBJECT: THREE MONTHS TO: KFA TEAM FROM: JOHN WEAVER – Chief Strategist Overview: Just over three months ago Governor Kasich became the last major candidate to announce he was running for President. We are now a little over three months away from the first caucuses and votes. As we near the halfway point between our announcement and the voters finally weighing in and the third debate, now is the time to assess our standing and our path to the nomination. In short, the Governor is well-positioned in New Hampshire and for the long road to the nomination. Right Message: We’ve received results back from our New Hampshire poll, conducted by Christine Matthews. The results are very encouraging. Our favorables and ballot tests are strong and the results show that voters support Governor Kasich’s policy reforms and message. The coming debates coupled with continued events in New Hampshire will allow the Governor to forcefully lay out his fiscal and economic vision, buttressed by his strong pro-growth record. This is a winning message. Our polling shows that New Hampshire voters value Governor Kasich’s profile. Voters want a candidate who has balanced budgets and created surpluses, who they also believe cares about them and will work across party lines to get things done. This is John Kasich in a nutshell. Total Very Important Important 92% 60% Has balanced budgets and created surpluses 86% 59% Cares about people like me 85% 59% Will work across the aisle to get things done 84% 40% Has national security experience 79% 42% Has cut taxes 48% 14% Has been a governor Voters also respond to the Governor’s record and his plan for the future: Total More Favorable Less Favorable No More Fav Much Smwt Smwt Much Difference 72% 42% 30% 6% 4% 19% Cut personal and corporate taxes so families and job creators keep more of what they earn. -

Clinton Leads in Pennsylvania, Ohio; Ties Bush in Florida, Quinnipiac University Swing State Poll Finds

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director, (203) 535-6203 Tim Malloy, Assistant Director (203) 645-8043 Rubenstein Associates, Inc., Public Relations Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: FEBRUARY 3, 2015 CLINTON LEADS IN PENNSYLVANIA, OHIO; TIES BUSH IN FLORIDA, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY SWING STATE POLL FINDS --- FLORIDA: Clinton 44 – Bush 43 OHIO: Clinton 47 – Bush 36 PENNSYLVANIA: Clinton 50 – Christie 39 A first look at three critical swing states, Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania, for the 2016 presidential election is good news for former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who tops possible Republican contenders in every matchup, except Florida, where she ties former Gov. Jeb Bush, and Ohio, where she ties Gov. John Kasich, according to a Quinnipiac University Swing State Poll released today. Overall, Gov. Bush runs best of any Republican listed against Clinton, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll finds. The Swing State Poll focuses on Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania because since 1960 no candidate has won the presidential race without taking at least two of these three states. Clinton’s favorability rating tops 50 percent in each state, while Republican ratings range from negative to mixed to slightly positive, except for Bush in Florida and Kasich in Ohio. Of three “Native Son” candidates, measured against Clinton only in their home states, only Ohio Gov. John Kasich gives the Democrat a good run, getting 43 percent to her 44 percent. Matchups between Clinton and her closest Republican opponent in each state show: Florida: Clinton at 44 percent to Bush’s 43 percent; Ohio: Clinton over Bush 47 – 36 percent; Pennsylvania: Clinton tops New Jersey Gov. -

Museum Seeks Public's Help to Replace Roof of Historic Barn

Hardin County’s KENTON TIMES www.kentontimes.com Kenton, Ohio — Saturday, September 22, 2012 USPS 584-440 50 cents area high school football scores Cooler for O-G . .52 the weekend Ada/Bluffton set for P-G . .40 Today, cloudy to partly Kenton . .16 1:30 p.m. in Ada H. Northern . .0 cloudy. Chance of show- ers. Lower 60s. R’mont/USV to play Riverdale . .21 Ben Logan/Tippe- Sunday, partly cloudy. Highs in the upper 50s. Hardin County News at 3 p.m. today. Buck Central . .20 canoe 10 a.m. start More weather P-5 by Hardin County People C + M Y Museum seeks public’s help to replace roof of historic barn By DAN ROBINSON Times staff writer The barn at the Hardin County Historical Museum in Kenton may be the largest artifact in its collection and it is in need of repair to survive. Caretaker Tim Striker said the barn at the Hardin County Farm Museum, locat- ed just east of the fair- grounds, was built 100 years ago and has stood the test of time until recently. A effort is underway to help the county raise funding to have the large structure’s roof replaced and restored so the old barn can live a new productive century. The barn was built in 1912 or 1913, said Striker, after its predecessor was burned to the ground following a thun- derstorm in July 1912. Times photo/Dan Robinson Workers witnessed the light- ning bolt hit the 60 x 80 foot Pumpkin prize building at 5 p.m. -

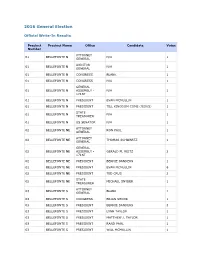

2016 General Write-In Results

2016 General Election Official Write-In Results Precinct Precinct Name Office Candidate Votes Number ATTORNEY 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 GENERAL AUDITOR 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 GENERAL 01 BELLEFONTE N CONGRESS BLANK 1 01 BELLEFONTE N CONGRESS N/A 1 GENERAL 01 BELLEFONTE N ASSEMBLY - N/A 1 171ST 01 BELLEFONTE N PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 1 01 BELLEFONTE N PRESIDENT TILL KINGDOM COME (JESUS) 1 STATE 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 TREASURER 01 BELLEFONTE N US SENATOR N/A 1 ATTORNEY 02 BELLEFONTE NE RON PAUL 1 GENERAL ATTORNEY 02 BELLEFONTE NE THOMAS SCHWARTZ 1 GENERAL GENERAL 02 BELLEFONTE NE ASSEMBLY - GERALD M. REITZ 2 171ST 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 1 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 6 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT TED CRUS 2 STATE 02 BELLEFONTE NE MICHAEL SNYDER 1 TREASURER ATTORNEY 03 BELLEFONTE S BLANK 1 GENERAL 03 BELLEFONTE S CONGRESS BRIAN SHOOK 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 3 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT LYNN TAYLOR 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT MATTHEW J. TAYLOR 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT RAND PAUL 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT WILL MCMULLIN 1 ATTORNEY 04 BELLEFONTE SE JORDAN D. DEVIER 1 GENERAL 04 BELLEFONTE SE CONGRESS JORDAN D. DEVIER 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT BURNEY SANDERS/MICHELLE OBAMA 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT DR. BEN CARSON 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT ELEMER FUDD 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLAN 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 2 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER/GEORGE M.W. -

October 2014 Poll (221 Respondents)

October 2014 Poll (221 Respondents) Red Maryland October 2014 Maryland GOP Survey 1. What county are you from? Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Allegany 1.4% 3 Anne Arundel 20.9% 46 Baltimore City 4.1% 9 Baltimore County 11.8% 26 Calvert 1.8% 4 Caroline 0.9% 2 Carroll 3.6% 8 Cecil 2.3% 5 Charles 2.7% 6 Dorchester 1.4% 3 Frederick 6.4% 14 Garrett 0.9% 2 Harford 5.0% 11 Howard 4.1% 9 Kent 1.4% 3 Montgomery 16.4% 36 Prince George's 4.5% 10 Queen Anne's 1.4% 3 St. Mary's 4.1% 9 Somerset 0.5% 1 Talbot 0.5% 1 Washington 1.8% 4 Wicomico 1.4% 3 Worcester 0.9% 2 answered question 220 skipped question 1 2. What is your age? Answer Options Response Percent Response Count 18 to 24 7.3% 16 25 to 34 18.6% 41 35 to 44 27.7% 61 45 to 54 20.5% 45 55 to 64 13.6% 30 65 to 74 10.0% 22 75 or older 2.3% 5 answered question 220 skipped question 1 3. What is your gender? Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Female 23.7% 51 Male 76.3% 164 answered question 215 skipped question 6 4. Are you a member of your County Republican Central Committee? Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Yes 8.6% 19 No 91.4% 201 answered question 220 skipped question 1 5. At this moment, which Republican who would be your first choice to be the Republican Nominee for President in 2016? Answer Options Response Percent Response Count Representative Michelle Bachman (MN) 0.0% 0 Former Ambassador John Bolton (MD) 0.9% 2 Former Governor Jeb Bush (FL) 5.0% 11 Herman Cain (GA) 0.0% 0 Dr.