Army Barracks in the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Army Hawaii Addresses Command/Division Brigade Battalion Address 18 MEDCOM 160 Loop Road, Ft

US Army Hawaii Addresses Command/Division Brigade Battalion Address 18 MEDCOM 160 Loop Road, Ft. Shafter, HI 96858 25 ID 25th Infantry Division Headquarters 2091 Kolekole Ave, Building 3004, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID (HQ) HHBN, 25th Infantry Division 25 ID Division Artillery (DIVARTY) HQ 25 ID DIVARTY HHB, 25th Field Artillery 1078 Waianae Avenue, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID DIVARTY 2-11 FAR 25 ID DIVARTY 3-7 FA 25 ID 2nd Brigade Combat Team HQ 1578 Foote Ave, Building 500, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 2 BCT 1-14 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 1-21 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 1-27 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 2-14 CAV 25 ID 2 BCT 225 BSB 25 ID 2 BCT 65 BEB 25 ID 2 BCT HHC, 2 SBCT 25 ID 25th Combat Aviation Brigade HQ 1343 Wright Avenue, Building 100, WAAF, HI 96854 25 ID 25th CAB 209th Support Battalion 25 ID 25th CAB 2nd Battalion, 25th Aviation 25 ID 25th CAB 2ndRegiment Squadron, 6th Cavalry 25 ID 25th CAB 3-25Regiment General Support Aviation 25 ID 3rd Brigade Combat Team HQ Battalion 1640 Waianae Ave, Building 649, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 3 BCT 2-27 INF 25 ID 3 BCT 2-35 INF BN 25 ID 3 BCT 29th BEB 25 ID 3 BCT 325 BSB 25 ID 3 BCT 325 BSTB 25 ID 3 BCT 3-4 CAV 25 ID 3 BCT HHC, 3 BCT 25 ID 25th Sustainment Brigade HQ 181 Sutton Street, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 25th SUST BDE 524 CSSB 25 ID 25th SUST BDE 25th STB 311 SC 311th Signal Command HQ Wisser Rd, Bldg 520, Ft. -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. ...... ..,. • NovinaWong City Clerk City Clark's Tai: [416) 392-8016 City Hall, 2nd Roor, West Fax:[416) 392-2980 100 Queen Street West [email protected] Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 http://www.city.toronto.on.ca ---- - - .. - - i April 26, 1999 j ,.-- ~~··,, "\ ... 1 1··, - ...._. ,... '•I ' . ~ ......... IN 1'HE MATTER OF THE ONTARIO HERITAGE ACT I -- - - - - - -· -- - - -- - . :! R.S.O. 1990, CHAPTER 0.18 AND ,;------·-. 2 STRA NAVENUE (ST EY BA CKS) CI1'Y OF TORONTO, PROVINCE OF ONTARIO NOTICE OF PASSING OF BY-LAW To: City of Toronto Ontario Heritage Foundation 100 Queen Street West 10 Adelaide Street East Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario M5H2N2 MSC 1J3 Take notice that the Council of the Corporation of the City of Toronto has passed By-law No. 188-1999 to designate 2 Strachan Avenue as being of architectural and historical value or interest. • Dated at Toronto this 30th day of April, 1999. Novina Wong City Clerk r ' .. .,. ~- ~ ...... ' Authority: Tor9nto Community Council Report No. 6, Clause No. 55, as adopted by City of Toronto Council on April 13, 14 and 15, 1999 Enacted by Council: April 15, 1999 CITY OF TORONTO BY-LAW No. 188-1999 t/' / / To designate the property at 2 Strachan Avenue (Stanley Barracks) as being of architectural and historical value or interest. -

Royal Artillery Barracks and Royal Military Repository Areas

CHAPTER 7 Royal Artillery Barracks and Royal Military Repository Areas Lands above Woolwich and the Thames valley were taken artillery companies (each of 100 men), headquartered with JOHN WILSON ST for military use from 1773, initially for barracks facing their guns in Woolwich Warren. There they assisted with Woolwich Common that permitted the Royal Regiment of Ordnance work, from fusefilling to proof supervising, and Artillery to move out of the Warren. These were among also provided a guard. What became the Royal Regiment Britain’s largest barracks and unprecedented in an urban of Artillery in 1722 grew, prospered and spread. By 1748 ARTILLERY PLACE Greenhill GRAND DEPOT ROAD context. The Board of Ordnance soon added a hospi there were thirteen companies, and further wartime aug Courts tal (now Connaught Mews), built in 1778–80 and twice mentations more than doubled this number by the end CH REA ILL H enlarged during the French Wars. Wartime exigencies also of the 1750s. There were substantial postwar reductions saw the Royal Artillery Barracks extended to their present in the 1760s, and in 1771 the Regiment, now 2,464 men, Connaught astonishing length of more than a fifth of a mile 0( .4km) was reorganized into four battalions each of eight com Mews in 1801–7, in front of a great grid of stables and more panies, twelve of which, around 900 men, were stationed barracks, for more than 3,000 soldiers altogether. At the in Woolwich. Unlike the army, the Board of Ordnance D St George’s A same time more land westwards to the parish boundary required its officers (Artillery and Engineers) to obtain Royal Artillery Barracks Garrison Church GRAND DEPOT RD O R was acquired, permitting the Royal Military Repository to a formal military education. -

Schofield Barracks, 27Th Infantry Regiment

#191 ROBERT KINZLER: SCHOFIELD BARRACKS, 27TH INFANTRY REGIMENT John Martini (JM): It's December 3, 1991. My name is Ranger John Martini from the National Park Service. We're doing [an] oral history interview videotape with Mr. Robert Kinzler. Mr. Kinzler was a solider stationed at Schofield Barracks, 27th Infantry Regiment on December 7, 1941. At that time, he was a Private Third Class radio operator. He was then nineteen years of age. This oral history videotape is being produced in conjunction with the National Park Service, USS ARIZONA Memorial and KHET-TV. So, thanks for coming to speak with us. And the first question I always ask is when did you enlist and where did you enlist? Robert Kinzler (RK): I enlisted on the 24th of June, 1940 at Newark, New Jersey, and requested service in Hawaii. My purpose in doing that was to try to win an appointment to West Point by attending the West Point prep school which was being conducted here, or at the Schofield Barracks at the time. They had another one at Fort Dix, New Jersey, but that was only a few miles from my home, so I opted for Hawaii. And it took three months to get here. I didn't arrive here until early September, 1940 on the USAT REPUBLIC, a transport, which brought me from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Brooklyn Army base to Panama, to San Francisco, to Hawaii. I got here and they off loaded us from the ship, put us on trucks, drove us a few blocks to the Iwilei Railroad Station. -

An Historical Overview of Vancouver Barracks, 1846-1898, with Suggestions for Further Research

Part I, “Our Manifest Destiny Bids Fair for Fulfillment”: An Historical Overview of Vancouver Barracks, 1846-1898, with suggestions for further research Military men and women pose for a group photo at Vancouver Barracks, circa 1880s Photo courtesy of Clark County Museum written by Donna L. Sinclair Center for Columbia River History Funded by The National Park Service, Department of the Interior Final Copy, February 2004 This document is the first in a research partnership between the Center for Columbia River History (CCRH) and the National Park Service (NPS) at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The Park Service contracts with CCRH to encourage and support professional historical research, study, lectures and development in higher education programs related to the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site and the Vancouver National Historic Reserve (VNHR). CCRH is a consortium of the Washington State Historical Society, Portland State University, and Washington State University Vancouver. The mission of the Center for Columbia River History is to promote study of the history of the Columbia River Basin. Introduction For more than 150 years, Vancouver Barracks has been a site of strategic importance in the Pacific Northwest. Established in 1849, the post became a supply base for troops, goods, and services to the interior northwest and the western coast. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century soldiers from Vancouver were deployed to explore the northwest, build regional transportation and communication systems, respond to Indian-settler conflicts, and control civil and labor unrest. A thriving community developed nearby, deeply connected economically and socially with the military base. From its inception through WWII, Vancouver was a distinctly military place, an integral part of the city’s character. -

Investigating Explore Important Themes from Scotland’S History

A royal palace and military stronghold, where pupils can INVESTIGATING explore important themes from Scotland’s history. STIRLING CASTLE Information for teachers EDUCATION INVESTIGATING HISTORIC SITES: SITES 2 stirling castle Welcome to Stirling Castle Contents Stirling Castle is one of Scotland’s most Special activities for schools P4 magnificent, built on a rocky outcrop There are many activities programmed Supporting learning and commanding a view for many to take place every year for schools at and teaching miles around. It was built as an almost Stirling Castle. In the past, activities impregnable fortification, and visitors have included storytelling with P6 can explore many aspects of its long puppets for early years groups, art Integrating a visit with military history, particularly during the activities based on decoration in classroom studies Wars of Independence in the 1300s. the castle and two-site events at But it was also an important and Bannockburn and Stirling. P8 luxurious royal palace. Visitors today can Timeline gain an insight into the life of Scotland’s Visit the Historic Scotland website royal court, especially that of James V. to download this year’s Schools Programme. P10 Using this pack Stirling Castle: www.historic-scotland.gov.uk This resource pack is designed for a historical overview In addition to events organised by teachers planning to visit Stirling Castle Historic Scotland, handling boxes are with their pupils. It includes: P12 available for the use of pupils free of Themed teacher-led tours • Suggestions for how a visit to charge at the Regimental Museum of Stirling Castle can support delivery the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, P13 of the Curriculum for Excellence situated within the castle. -

Royal Artillery Barracks and Royal Military Repository Areas

DRAFT CHAPTER 7 – ROYAL ARTILLERY BARRACKS AND ROYAL MILITARY REPOSITORY AREAS Lands above Woolwich and the Thames valley were taken for military use from 1773, initially for barracks facing Woolwich Common that permitted the Royal Regiment of Artillery to move out of the Warren. These were among Britain’s largest barracks and unprecedented in an urban context. The Board of Ordnance soon added a hospital (now Connaught Mews), built in 1778–80 and twice enlarged during the French Wars. Wartime exigencies also saw the Royal Artillery Barracks extended to their present astonishing length of more than a fifth of a mile in 1801–7, in front of a great grid of stables and more barracks, for more than 3,000 soldiers altogether. At the same time more land westwards to the parish boundary was acquired, permitting the Royal Military Repository to move up from the Warren in 1802 and, through the ensuing war, to reshape an irregular natural terrain for an innovative training ground, a significant aspect of military professionalization. The resiting there in 1818–20 of the Rotunda, a temporary royal marquee from the victory celebrations of 1814 at Carlton House recast as a permanent military museum, together with the remaking of adjacent training fortifications, settled the topography of a unique landscape that served training, pleasure-ground and commemorative purposes. There have been additions, such as St George’s Garrison Church in the 1860s, and rebuildings, as after bomb damage in the 1940s. More changes have come since the departure of the Royal Artillery in 2007 when the Regiment’s headquarters moved to Larkhill in Wiltshire. -

Sites-Guide.Pdf

EXPLORE SCOTLAND 77 fascinating historic places just waiting to be explored | 3 DISCOVER STORIES historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place OF PEOPLE, PLACES & POWER Over 5,000 years of history tell the story of a nation. See brochs, castles, palaces, abbeys, towers and tombs. Explore Historic Scotland with your personal guide to our nation’s finest historic places. When you’re out and about exploring you may want to download our free Historic Scotland app to give you the latest site updates direct to your phone. ICONIC ATTRACTIONS Edinburgh Castle, Iona Abbey, Skara Brae – just some of the famous attractions in our care. Each of our sites offers a glimpse of the past and tells the story of the people who shaped a nation. EVENTS ALL OVER SCOTLAND This year, yet again we have a bumper events programme with Spectacular Jousting at two locations in the summer, and the return of festive favourites in December. With fantastic interpretation thrown in, there’s lots of opportunities to get involved. Enjoy access to all Historic Scotland attractions with our great value Explorer Pass – see the back cover for more details. EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS | 5 Must See Attraction EDINBURGH AND THE LOTHIANS EDINBURGH CASTLE No trip to Scotland’s capital is complete without a visit to Edinburgh Castle. Part of The Old and New Towns 6 EDINBURGH CASTLE of Edinburgh World Heritage Site and standing A mighty fortress, the defender of the nation and majestically on top of a 340 million-year-old extinct a world-famous visitor attraction – Edinburgh Castle volcano, the castle is a powerful national symbol. -

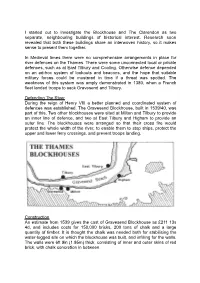

Gravesend Blockhouse and the Clarendon

I started out to investigate the Blockhouse and The Clarendon as two separate, neighbouring buildings of historical interest. Research soon revealed that both these buildings share an interwoven history, so it makes sense to present them together. In Medieval times there were no comprehensive arrangements in place for river defences on the Thames. There were some unconnected local or private defences, such as at East Tilbury and Cooling. Otherwise defence depended on an ad-hoc system of lookouts and beacons, and the hope that suitable military forces could be mustered in time if a threat was spotted. The weakness of this system was amply demonstrated in 1380, when a French fleet landed troops to sack Gravesend and Tilbury. Defending The River During the reign of Henry VIII a better planned and coordinated system of defences was established. The Gravesend Blockhouse, built in 1539/40, was part of this. Two other blockhouses were sited at Milton and Tilbury to provide an inner line of defence, and two at East Tilbury and Higham to provide an outer line. The blockhouses were arranged so that their cross fire would protect the whole width of the river, to enable them to stop ships, protect the upper and lower ferry crossings, and prevent troops landing. Construction An estimate from 1539 gives the cost of Gravesend Blockhouse as £211 13s 4d, and includes costs for 150,000 bricks, 200 tons of chalk and a large quantity of timber. It is thought the chalk was needed both for stabilising the water-logged site on which the blockhouse was built, and infilling for the walls. -

Tilbury Fort Conservation Plan Draft V1 Prepared for English Heritage March 2018

Tilbury Fort Conservation Plan Draft v1 Prepared for English Heritage March 2018 Alan Baxter Draft How to use this document This document has been designed to be viewed digitally. It will work best on Comments Adobe Reader or Adobe Acrobat Pro versions X or DC or later on a PC or laptop. The document can be annotated with comments and amendments using the standard Adobe commenting tools. The comments tools will differ depending Navigation on your reader – here are instructions for Acrobat X and Adobe DC Reader: The document can be navigated in several ways: • Acrobat X: https://www.adobe.com/content/dam/Adobe/en/feature-details/ • Via the bookmarks panel on the left hand side of the screen (revealed by acrobatpro/pdfs/adding-comments-to-a-pdf-document.pdf clicking ). • Adobe DC Reader: https://helpx.adobe.com/reader/using/share-comment- • Clicking on hyperlinks in the contents page or embedded in the text review.html (identified by blue text). • Using the search function (press Ctrl + F on your keyboard to bring up the Gazetteer (to follow) search box). If you are interested in one specific part of site you can go straight to the Gazetteer (Location of Gazetteer). It opens with navigation plans; clicking the • Using buttons at the bottom of each page: label for each area will take you to the relevant details. To access the navigation Contents plans at any time, click the ** button. Previous view Forward and back Site Plan Part 1: Conservation Plan Part 2: Gazetteer and Supporting Information (to follow) Tilbury Fort Conservation Plan / -

Thematic Survey of the Ordnance Yards and Magazine Depots

THEMATIC SURVEY OF THE ORDNANCE YARDS AND MAGAZINE DEPOTS SUMMARY REPORT THEMATIC LISTING PROGRAMME JEREMY LAKE FINAL DRAFT JANUARY 2003 Not to be cited without acknowledgement to English Heritage Thematic Survey of the Ordnance Yards and Magazine Depots Summary Report page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 5 2.0 A BRIEF BACKGROUND TO THE ORDNANCE YARDS 7 3.0 THE BUILDING TYPES 17 3.1 Store Magazines 17 3.2 Receipt & Issue Magazines 17 3.3 Shoe Rooms 18 3.4 Examining Rooms (Shifting Houses pre 1875) 18 3.5 Proof Houses 18 3.6 Buildings for the Repair of Gunpowder 19 3.7 Original Laboratory Buildings 19 3.8 Early Shell Stores 20 3.9 Fuze and Tube Stores 20 3.10 Empty Case Stores 21 3.11 Early Cartridge and Shell Filling and Packing, and related Buildings 21 3.12 Store for planks, flannel cartridges, Foreman's Office and Printing Press 22 Room 3.13 Storekeeper's Office. Rooms for Storekeeper, Clerk, Messenger and 22 Records 3.14 Pattern & Class Rooms 22 3.15 Smithery 22 3.16 Accommodation block for Messengers, Foremen and Police Sergeants, 22 with Artificers' Shop 3.17 Painters' Shops 22 3.18 Shifting Rooms 23 3.19 Truck Shed 23 3.20 Shell Filling Rooms 23 3.21 QF Shell Filling Rooms 23 3.22 Expense Magazine for Shell Filling Rooms 23 3.23 Unheading Room 24 3.24 Shell Emptying Rooms 24 2 3.25 Boiler House 24 3.26 Detonator Stores 24 3.27 Wet Guncotton Magazines 25 3.28 Dry Guncotton Magazines 25 3.29 Mine and Countermine Stores 25 3.30 Mine Examining Rooms 25 3.31 Filled Shell Stores (after the Admiralty takeover) 26 3.32 Cordite Magazines 26 3.33 Cordite -

Barracks and Conscription: Civil-Military Relations in Europe from 1500 by John Childs

Barracks and Conscription: Civil-Military Relations in Europe from 1500 by John Childs To operate efficiently, armed forces require physical separation from civilian society, achieved usually through the em- ployment of mercenaries, conscription and the provision of discrete military accommodation. War became more "popu- lar" during the religious conflicts between 1520 and 1648 diluting civil-military distinctions but the advent of regular, uni- formed, professional armies in the second half of the 17th century re-established clearer segregation. The adoption of compulsory, male, military service during the 19th and 20th centuries again brought the military and the civil into closer contact. Since 1991 small, professional, more cost-effective forces have gradually replaced mass conscript armies thus re-sharpening the civil-military divide. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Military accommodation 3. Conscription 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation Introduction Soldiers differ from civilians in dress, their possession of the legal right to kill and injure, adherence to particular codes of honour and behaviour, and submission to military law.1 The employment of mercenaries, which occurred extensively before 1648 and again during the later decades of the 20th century, has tended to blur these boundaries. Mercenaries frequently wear no official uniform and have often operated outside both military law and the command structures of na- tional armed forces. Legally they are civilians. The most recent manifestation has been the employment of tens of thou- sands of substantially-armed mercenaries wearing civilian clothes – euphemistically referred to as "security guards", "contractors" and "reconstruction workers" – in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, as well as the Trans-Caucasus, Iraq and Afghanistan.