Fortifications on Maine's Northeast Boundary, 1828-1845

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penobscot Rivershed with Licensed Dischargers and Critical Salmon

0# North West Branch St John T11 R15 WELS T11 R17 WELS T11 R16 WELS T11 R14 WELS T11 R13 WELS T11 R12 WELS T11 R11 WELS T11 R10 WELS T11 R9 WELS T11 R8 WELS Aroostook River Oxbow Smith Farm DamXW St John River T11 R7 WELS Garfield Plt T11 R4 WELS Chapman Ashland Machias River Stream Carry Brook Chemquasabamticook Stream Squa Pan Stream XW Daaquam River XW Whitney Bk Dam Mars Hill Squa Pan Dam Burntland Stream DamXW Westfield Prestile Stream Presque Isle Stream FRESH WAY, INC Allagash River South Branch Machias River Big Ten Twp T10 R16 WELS T10 R15 WELS T10 R14 WELS T10 R13 WELS T10 R12 WELS T10 R11 WELS T10 R10 WELS T10 R9 WELS T10 R8 WELS 0# MARS HILL UTILITY DISTRICT T10 R3 WELS Water District Resevoir Dam T10 R7 WELS T10 R6 WELS Masardis Squapan Twp XW Mars Hill DamXW Mule Brook Penobscot RiverYosungs Lakeh DamXWed0# Southwest Branch St John Blackwater River West Branch Presque Isle Strea Allagash River North Branch Blackwater River East Branch Presque Isle Strea Blaine Churchill Lake DamXW Southwest Branch St John E Twp XW Robinson Dam Prestile Stream S Otter Brook L Saint Croix Stream Cox Patent E with Licensed Dischargers and W Snare Brook T9 R8 WELS 8 T9 R17 WELS T9 R16 WELS T9 R15 WELS T9 R14 WELS 1 T9 R12 WELS T9 R11 WELS T9 R10 WELS T9 R9 WELS Mooseleuk Stream Oxbow Plt R T9 R13 WELS Houlton Brook T9 R7 WELS Aroostook River T9 R4 WELS T9 R3 WELS 9 Chandler Stream Bridgewater T T9 R5 WELS TD R2 WELS Baker Branch Critical UmScolcus Stream lmon Habitat Overlay South Branch Russell Brook Aikens Brook West Branch Umcolcus Steam LaPomkeag Stream West Branch Umcolcus Stream Tie Camp Brook Soper Brook Beaver Brook Munsungan Stream S L T8 R18 WELS T8 R17 WELS T8 R16 WELS T8 R15 WELS T8 R14 WELS Eagle Lake Twp T8 R10 WELS East Branch Howe Brook E Soper Mountain Twp T8 R11 WELS T8 R9 WELS T8 R8 WELS Bloody Brook Saint Croix Stream North Branch Meduxnekeag River W 9 Turner Brook Allagash Stream Millinocket Stream T8 R7 WELS T8 R6 WELS T8 R5 WELS Saint Croix Twp T8 R3 WELS 1 Monticello R Desolation Brook 8 St Francis Brook TC R2 WELS MONTICELLO HOUSING CORP. -

KENNEBEC SALMON RESTORATION: Innovation to Improve the Odds

FALL/ WINTER 2015 THE NEWSLETTER OF MAINE RIVERS KENNEBEC SALMON RESTORATION: Innovation to Improve the Odds Walking thigh-deep into a cold stream in January in Maine? The idea takes a little getting used to, but Paul Christman doesn’t have a hard time finding volunteers to do just that to help with salmon egg planting. Christman is a scientist with Maine Department of Marine Resource. His work, patterned on similar efforts in Alaska, involves taking fertilized salmon eggs from a hatchery and planting them directly into the cold gravel of the best stream habitat throughout the Sandy River, a Kennebec tributary northwest of Waterville. Yes, egg planting takes place in the winter. For Maine Rivers board member Sam Day plants salmon eggs in a tributary of the Sandy River more than a decade Paul has brought staff and water, Paul and crews mimic what female salmon volunteers out on snowshoes and ATVs, and with do: Create a nest or “redd” in the gravel of a river waders and neoprene gloves for this remarkable or stream where she plants her eggs in the fall, undertaking. Finding stretches of open stream continued on page 2 PROGRESS TO UNDERSTAND THE HEALTH OF THE ST. JOHN RIVER The waters of the St. John River flow from their headwaters in Maine to the Bay of Fundy, and for many miles serve as the boundary between Maine and Quebec. Waters of the St. John also flow over the Mactaquac Dam, erected in 1968, which currently produces a substantial amount of power for New Brunswick. Efforts are underway now to evaluate the future of the Mactaquac Dam because its mechanical structure is expected to reach the end of its service life by 2030 due to problems with the concrete portions of the dam’s station. -

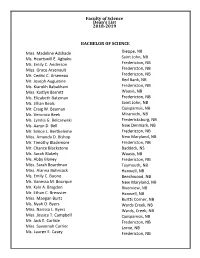

Faculty of Science Dean's List 2018-2019

Faculty of Science Dean's List 2018-2019 BACHELOR OF SCIENCE Miss. Madeline Adshade Dieppe, NB Ms. Heartswill E. Agbaku Saint John, NB Ms. Emily C. Anderson Fredericton, NB Miss. Grace Arsenault Fredericton, NB Mr. Cedric C. Arseneau Fredericton, NB Mr. Joseph Augustine Red Bank, NB Ms. Kiarokh Babakhani Fredericton, NB Miss. Kaitlyn Barrett Waasis, NB Ms. Elizabeth Bateman Fredericton, NB Ms. Jillian Beals Saint John, NB Mr. Craig W. Beaman Quispamsis, NB Ms. Veronica Beek Miramichi, NB Ms. Lyndia G. Belczewski Fredericksburg, NB Ms. Aaryn D. Bell New Denmark, NB Mr. Simon L. Bertheleme Fredericton, NB Miss. Amanda D. Bishop New Maryland, NB Mr. Timothy Blackmore Fredericton, NB Mr. Chance Blackstone Baddeck, NS Ms. Sarah Blakely Waasis, NB Ms. Abby Blaney Fredericton, NB Miss. Sarah Boardman Taymouth, NB Miss. Alanna Bohnsack Hanwell, NB Ms. Emily C. Boone Beechwood, NB Ms. Vanessa M. Bourque New Maryland, NB Mr. Kyle A. Bragdon Riverview, NB Mr. Ethan C. Brewster Hanwell, NB Miss. Maegan Burtt Burtts Corner, NB Ms. Nyah D. Byers Wards Creek, NB Miss. Narissa L. Byers Wards, Creek, NB Miss. Jessica T. Campbell Quispamsis, NB Mr. Jack E. Carlisle Fredericton, NB Miss. Savannah Carrier Lorne, NB Ms. Lauren E. Casey Fredericton, NB Mr. Kevin D. Comeau Mr. Nicholas F. Comeau Miss Emma M. Connell BACHELOR OF SCIENCE Ms. Jennifer Chan Fredericton, NB Mr. Benjamin Chase Fredericton, NB Mr. Matthew L. Clinton Fredericton, NB Miss. Grace M. Coles North Milton, PE Ms. Emma A. Collings Montague, PE Mr. Jordan W. Conrad Dartmouth, NS Mr. Samuel R. Cookson Quispamsis, NB Ms. Kelsey E. -

Industrial Park

VILLAGE OF PERTH-ANDOVER, N.B. Village of WH ET ERE P LS ME Perth-Andover EOPLE AND T RAI Perth-Andover Industrial Park "Home of the Best Power Rates in New Brunswick” CONTACT Mr. Dan Dionne Chief Administrative Officer Village of Perth-Andover 1131 West Riverside Drive Perth-Andover, New Brunswick E7H 5G5 Telephone: (506) 273-4959 Facsimile: (506) 273-4947 Email: [email protected] Website: www.perth-andover.com HISTORY OVERVIEW In 1991 the municipality established a 25 acre block of land for an industrial Perth-Andover is located on the Saint John River, 40 kilometres south of park. Several businesses have established themselves in the Industrial Grand Falls near the mouth of the Tobique River. Perth is located on the Park, and the municipality is currently expanding the park to accommodate east side of the river and Andover is located on the west side. The two future demand. Businesses wishing to establish in the park can expect the villages were amalgamated in 1966 and have a population service area in Mayor and Council to do whatever possible to assist them. Perth-Andover excess of 6,000 people. Nestled between the rolling hills of the upper river is ideally located for businesses looking for excellent access to the United valley, this picturesque village is often referred to as the "Gateway to the States and to Ontario and Quebec. Combine this with an excellent quality of Tobique". The Municipality is ten kilometres west of the U.S. border and life and you have one of the most attractive areas in the province for approximately 80 kilometres north of Woodstock and the entrance to locating new industry. -

US Army Hawaii Addresses Command/Division Brigade Battalion Address 18 MEDCOM 160 Loop Road, Ft

US Army Hawaii Addresses Command/Division Brigade Battalion Address 18 MEDCOM 160 Loop Road, Ft. Shafter, HI 96858 25 ID 25th Infantry Division Headquarters 2091 Kolekole Ave, Building 3004, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID (HQ) HHBN, 25th Infantry Division 25 ID Division Artillery (DIVARTY) HQ 25 ID DIVARTY HHB, 25th Field Artillery 1078 Waianae Avenue, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID DIVARTY 2-11 FAR 25 ID DIVARTY 3-7 FA 25 ID 2nd Brigade Combat Team HQ 1578 Foote Ave, Building 500, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 2 BCT 1-14 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 1-21 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 1-27 IN BN 25 ID 2 BCT 2-14 CAV 25 ID 2 BCT 225 BSB 25 ID 2 BCT 65 BEB 25 ID 2 BCT HHC, 2 SBCT 25 ID 25th Combat Aviation Brigade HQ 1343 Wright Avenue, Building 100, WAAF, HI 96854 25 ID 25th CAB 209th Support Battalion 25 ID 25th CAB 2nd Battalion, 25th Aviation 25 ID 25th CAB 2ndRegiment Squadron, 6th Cavalry 25 ID 25th CAB 3-25Regiment General Support Aviation 25 ID 3rd Brigade Combat Team HQ Battalion 1640 Waianae Ave, Building 649, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 3 BCT 2-27 INF 25 ID 3 BCT 2-35 INF BN 25 ID 3 BCT 29th BEB 25 ID 3 BCT 325 BSB 25 ID 3 BCT 325 BSTB 25 ID 3 BCT 3-4 CAV 25 ID 3 BCT HHC, 3 BCT 25 ID 25th Sustainment Brigade HQ 181 Sutton Street, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857 25 ID 25th SUST BDE 524 CSSB 25 ID 25th SUST BDE 25th STB 311 SC 311th Signal Command HQ Wisser Rd, Bldg 520, Ft. -

New Sweden, Westmanland, Madawaska Lake, Stockholm, Woodland, Perham, & Caribou PB

1870 -2010 Maine Swedish Colony MIDSOMMAR 18-20 June, 2010 Friday-Sunday Maine Midsommar Festival m n.co unca lliamLD 1870 ©2009 Wi Free Souvenir Calendar, Guide, and Map Maine Swedish Colony: New Sweden, Westmanland, Madawaska Lake, Stockholm, Woodland, Perham, & Caribou PB Local Banking since 1936! Keep your money at Home, where it helps build AROOSTOOK our Community. Monday-Saturday • Swedish Specialty Foods SAVINGS & LOAN 10:00 AM – 5:30 PM • Scandinavian Sweaters [email protected] • Crystal Dinnerware Aroostook County Federal • Clogs • Jewelry • Platinum Troll Beads Dealer Your Home Bank Savings and Loan Association • Table Linens • Bridal Registry FDIC Insured Equal Housing Lender PB Places to stay Places To Eat Caribou Within the Colony Burger Boy . Sweden Street . .498-2291 * Fieldstone Cabins and RV Park, Madawaska Lake Burger King . Bennett Drive . 498-3500 * Aunties Cabin, New Sweden, 207-896-7905 Delivering on Cindy’s Sub Shop . Sweden Street . .498-6021 * Up North Cabins, New Sweden (+camping & trailer sites) 207- Far East Kitchen . Bennett Drive . 493-7858 896-3328 SM Farm's Bakery . 118 Bennett Drive . 493-4508 * Paul Bondeson camping, New Sweden, 207-896-5553 A promise. Frederick’s South Side . South Main St. .498-3464 Greenhouse Restaurant . Rt. 1 & 164 . 498-3733 Caribou Houlton Farms Dairy (about 10 minutes south of New Sweden) (Ice Cream) . Bennett Drive . 498-8911 * Old Iron Inn B&B, 207-492-4766, 4 bedrooms Jade Palace Restaurant . Skyway Plaza, * Russell’s Motel, 207-498-2567, 14 units . Bennett Drive . 498-3648 * Caribou Inn and Convention Center, 73 rooms, McDonald’s . Bennett Drive . 498-2181 207-498-3733, Napoli's . -

This Document Was Retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act E-Register, Which Is Accessible Through the Website of the Ontario Heritage Trust At

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act e-Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre électronique. tenu aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. ...... ..,. • NovinaWong City Clerk City Clark's Tai: [416) 392-8016 City Hall, 2nd Roor, West Fax:[416) 392-2980 100 Queen Street West [email protected] Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N2 http://www.city.toronto.on.ca ---- - - .. - - i April 26, 1999 j ,.-- ~~··,, "\ ... 1 1··, - ...._. ,... '•I ' . ~ ......... IN 1'HE MATTER OF THE ONTARIO HERITAGE ACT I -- - - - - - -· -- - - -- - . :! R.S.O. 1990, CHAPTER 0.18 AND ,;------·-. 2 STRA NAVENUE (ST EY BA CKS) CI1'Y OF TORONTO, PROVINCE OF ONTARIO NOTICE OF PASSING OF BY-LAW To: City of Toronto Ontario Heritage Foundation 100 Queen Street West 10 Adelaide Street East Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario M5H2N2 MSC 1J3 Take notice that the Council of the Corporation of the City of Toronto has passed By-law No. 188-1999 to designate 2 Strachan Avenue as being of architectural and historical value or interest. • Dated at Toronto this 30th day of April, 1999. Novina Wong City Clerk r ' .. .,. ~- ~ ...... ' Authority: Tor9nto Community Council Report No. 6, Clause No. 55, as adopted by City of Toronto Council on April 13, 14 and 15, 1999 Enacted by Council: April 15, 1999 CITY OF TORONTO BY-LAW No. 188-1999 t/' / / To designate the property at 2 Strachan Avenue (Stanley Barracks) as being of architectural and historical value or interest. -

America's Color Coded War Plans and the Evolution of Rainbow Five

TABLE OF CONTENTS: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER I: THE MONROE DOCTRINE AND MILITARY PLANNING 8 CHAPTER II: MANIFEST DESTINY AND MILITARY PLANNING 42 CHAPTER III: THE EVOLUTION OF RAINBOW FIVE 74 CONCLUSION 119 BIBLIOGRAPHY 124 INTRODUCTION: During World War II, U.S. military forces pursued policies based in large part on the Rainbow Five war plan. Louis Morton argued in Strategy and Command: The First Two Years that “The early war plans were little more than abstract exercises and bore little relation to actual events.” 1 However, this thesis will show that the long held belief that the early war plans devised in the late 19 th and earlier 20 th centuries were exercises in futility is a mistaken one. The early color coded war plans served purposes far beyond that of just exercising the minds and intellect of the United States most gifted and talented military leaders. Rather, given the demands imposed by advances in military warfare and technology, contingency war planning was a necessary precaution required of all responsible powers at the dawn of the 20 th century. Also contrary to previous assumptions, America’s contingency war planning was a realistic response to the course of domestic and international affairs. The advanced war plan scenarios were based on actual real world alliances and developments in international relations, this truth defies previous criticisms that early war planners were not cognizant of world affairs or developments in U.S. bilateral relations with other nations. 2 This thesis reveals that the U.S. military’s color coded war plans were part of a clear, continuous evolution of American military strategy culminating in the creation of Rainbow Five, the Allied plan for victory during the Second World War. -

Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Maine Collection 7-1973 Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine Charles F. Wallace Jr. James M. Strunk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection Part of the Biology Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Hydrology Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Other Life Sciences Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Charles F. Jr. and Strunk, James M., "Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine" (1973). Maine Collection. 134. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/me_collection/134 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Collection by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVENTORY OF LAKE STUDIES IN MAINE By Charles F. Wallace, Jr. and James m. Strunk ,jitnt.e of ~lame Zfrxemtiue ~epnrlmeut ~fate Jhtuuiug ®£fit£ 189 ~fate ~treet, !>ugusht, ~nine 04330 KENNETH M. CURTIS WATER RESOURCES PLANNING GOVERNOR 16 WINTHROP STREET PHILIP M. SAVAGE TEL. ( 207) 289-3253 STATE PLANNING DIRECTOR July 16, 1973 Please find enclosed a copy of the Inventory of Lake Studies in Maine prepared by the Water Resources Planning Unit of the State Planning Office. We hope this will enable you to better understand the intensity and dir ection of lake studies and related work at various private and institutional levels in the State of Maine. Any comments or inquiries, which you may have concerning its gerieral content or specific studies, are welcomed. -

Politics of Education in Madawaska, 1842-1920

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Summer 8-21-2020 Language, Identity, and Citizenship: Politics of Education in Madawaska, 1842-1920 Elisa E A Sance University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Canadian History Commons, Other Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Sance, Elisa E A, "Language, Identity, and Citizenship: Politics of Education in Madawaska, 1842-1920" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3200. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3200 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LANGUAGE, IDENTITY, AND CITIZENSHIP: POLITICS OF EDUCATION IN MADAWASKA, 1842-1920 By Elisa Elisabeth Andréa Sance M.A. University of Maine, 2014 B.A. Université d’Angers, 2011 B.L.S. Université d’Angers, 2007 A.A. Université Picardie Jules Verne, 2006 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Advisor Scott W. See, Libra Professor Emeritus of History Richard W. Judd, Professor Emeritus of History Mazie Hough, Professor Emerita of History & Women’s, Gender, & Sexuality Studies Jane S. -

The Forgotten History of Maysville 18161883

LOST MAYSVILLE 1 LOST MAYSVILLE A BRIEF HISTORY OF AROOSTOOK COUNTY’S FORGOTTEN TOWN A Research Study by Evan Zarkadas 2 "I had visited many parks in Europe and America, where great wealth had been expended, and great displays were exhibited, but none had the same charm that compels me to visit it and admire its beautiful and valuable farms as had Maysville, whenever I can" - Francis E. Clark 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................. 7 Land and Resources .................................................. 11 Land Acquisition ....................................................... 13 Aroostook War and the Webster Ashburton Treaty . 27 Settlement after the Webster Ashburton Treaty ....... 35 Agricultural Development ........................................ 41 Economic and Political Development ....................... 49 Civil War ................................................................... 68 Post-Civil War Development .................................... 70 Conclusion ................................................................ 77 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would have been impossible without the support and guidance of Dr. Kimberly Sebold from the University of Maine at Presque Isle and her love for local history, the Presque Isle Historical Society, Kim Smith and Craig Green for their tremendous assistance. I am grateful to all those that helped me in the process of compiling and completing my research. This is a research projected for the community and this is where it belongs. 5 Bradley’s Island in the Aroostook River, just north of Presque Isle. “Where settlement began” 6 INTRODUCTION History is not just about the great empires, the wars and the old kings, it is also about the everyday community and the people who live in that community and form associations. As Shakespeare noted, there is a history in all men’s lives.1 Nearby History according to David E. -

CSD Code Census Subdivision (CSD) Name 2011 Income Score

2011 Income 2011 Education 2011 Housing 2011 Labour Force 2011 CWB 2011 Global Non‐ Type of 2011 NHS CSD Code Census subdivision (CSD) name Score Score Score Activity Score Score Response Province Collectivity Population 1001105 Portugal Cove South 67 36% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 160 1001113 Trepassey 90 42 95 71 74 35% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 545 1001131 Renews‐Cappahayden 78 46 95 82 75 35% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 310 1001144 Aquaforte 72 31% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 90 1001149 Ferryland 78 53 94 70 74 48% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 465 1001169 St. Vincent's‐St. Stephen's‐Peter's River 81 54 94 69 74 37% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 315 1001174 Gaskiers‐Point La Haye 71 39% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 235 1001186 Admirals Beach 79 22% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 85 1001192 St. Joseph's 72 27% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 125 1001203 Division No. 1, Subd. X 76 44 91 77 72 45% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 495 1001228 St. Bride's 76 38 96 78 72 24% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 295 1001281 Chance Cove 74 40% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 120 1001289 Chapel Arm 79 47 92 78 74 38% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 405 1001304 Division No. 1, Subd. E 80 48 96 78 76 20% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 2990 1001308 Whiteway 80 50 93 82 76 25% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 255 1001321 Division No. 1, Subd. F 74 41 98 70 71 45% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 550 1001328 New Perlican 66 28% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 120 1001332 Winterton 78 38 95 61 68 41% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 475 1001339 Division No.