In English, P.13, Fig. 16, Ref 10, Adobepdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laura Stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion

laura stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion Studia Fennica Folkloristica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Laura Stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion Finnish Literature Society • Helsinki 3 Studia Fennica Folkloristica 11 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via Helsinki University Library. © 2002 Laura Stark and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International. A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-366-9 (Print) ISBN 978-951-746-578-6 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-766-9 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 1235-1946 (Studia Fennica Folkloristica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sff.11 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. -

The Case of Karelia Stepanova, S

www.ssoar.info Tourism development in border areas: a benefit or a burden? The case of Karelia Stepanova, S. V. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Stepanova, S. V. (2019). Tourism development in border areas: a benefit or a burden? The case of Karelia. Baltic Region, 11(2), 94-111. https://doi.org/10.5922/2079-8555-2019-2-6 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-64250-8 Tourism TOURISM DEVELOPMENT Border regions are expected to IN BORDER AREAS: benefit from their position when it comes to tourism development. In A BENEFIT OR A BURDEN? this article, I propose a new ap- THE CASE OF KARELIA proach to interpreting the connec- tion between an area’s proximity to 1 S. V. Stepanova the national border and the devel- opment of tourism at the municipal level. The aim of this study is to identify the strengths and limita- tions of borderlands as regards the development of tourism in seven municipalities of Karelia. I examine summarised data available from online and other resources, as well as my own observations. Using me- dian values, I rely on the method of content analysis of strategic docu- ments on the development of cross- border municipalities of Karelia. -

Geographia Polonica Vol. 92 No. 4 (2019), the Northern Ladoga

Geographia Polonica 2019, Volume 92, Issue 4, pp. 409-428 https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0156 INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY AND SPATIAL ORGANIZATION POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES www.igipz.pan.pl www.geographiapolonica.pl THE NORTHERN LADOGA REGION AS A PROSPECTIVE TOURIST DESTINATION IN THE RUSSIAN-FINNISH BORDERLAND: HISTORICAL, CULTURAL, ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC ASPECTS Svetlana V. Stepanova Institute of Economics Karelian Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences 50 A. Nevskogo st., Petrozavodsk 185030, Republic of Karelia: Russia e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The work reported here has examined the transformation of the Northern Ladoga region (a natural and histori- cal region in the Russian-Finnish borderland) from ‘closed’ border area into a prospective tourist destination in the face of changes taking place in the 1990s. Three periods to the development of tourism in the region are identified, while the article goes on to explore general trends and features characterising the development of a tourist destination, with the focus on tourist infrastructure, the developing types of tourism and tourism- oriented projects. Measures to further stimulate tourism as an economic activity of the region are suggested. Key words tourism development • the Northern Ladoga region • tourist destination • Russian-Finnish border- land • Republic of Karelia • political and socio-economic changes Introduction The region was chosen for its geographi- cal and historical retrospectivity, its attractive This paper examines tourist and recreational natural and cultural resources and develop- development taking place in the Northern ing tourist infrastructure and its services deal- Ladoga region (“the region”) of the Russian- ing with increasing numbers of visitors. -

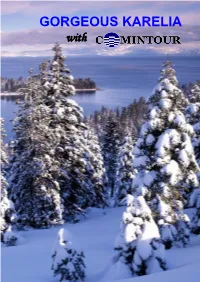

GORGEOUS KARELIA With

GORGEOUS KARELIA with 1 The tours presented in this brochure aim to country had been for centuries populated by the introduce customers to the unique beauty and Russian speaking Pomors – proud independent folk culture of the area stretching between the southern that were at the frontier of the survival of the settled coast of the White Sea and the Ladoga Lake. civilization against the harshness of the nature and Karelia is an ancient land that received her name paid allegiance only to God and their ancestors. from Karelians – Finno-Ugric people that settled in that area since prehistoric times. Throughout the For its sheer territory size (half of that of Germany) history the area was disputed between the Novgorod Karelia is quite sparsely populated, making it in fact Republic (later incorporated into Russian Empire) the biggest natural reserve in Europe. The and Kingdom of Sweden. In spite of being Orthodox environment of this part of Russia is very green and Christians the Karelians preserved unique feel of lavish in the summer and rather stern in the winter, Finno-Ugric culture, somehow similar to their but even in the cold time of the year it has its own Finnish cousins across the border. East of the unique kind of beauty. Fresh water lakes and rivers numbered in tens of thousands interlace with the dense taiga pine forest and rocky outcrops. Wherever you are in Karelia you never too far from a river or lake. Large deposits of granite and other building stones give the shores of Karelian lakes a uniquely romantic appearance. -

The Ruskeala Mining History Monument: State, Perspectives of Protection and Usage

http://www.progeo.se NO. 4 2010 View on the lake of the Ruskeala main quarry from the tourist path. Photo of M.Vdovets The Ruskeala mining history monument: state, perspectives of protection and usage Marina Vdovets, Yuri Lyahnitsky, VSEGEI, Sredny pr., 74, 199106 Saint-Petersburg, Russia marble layers. The marbles are characterized by fine- grained structure and diverse coloration from dark-grey The Ruskeala marble quarries represent a mining his- to white, sometimes with green stripes and nests up to tory of Sweden, Russia, Finland, and Karelia. The a few centimeters wide. The total thickness of the pro- quarries are located in the Sortavala District (Republic ductive horizon is up to 600 m. Banded marble, cha- of Karelia, Russia), in the northwestern part of Ruskea- racterized by alternation of grey, almost black, green la village on the White and Green hills, named accord- and white stripes has the best decorative properties. ing to the colors of marbles, which formed them. The first exploitation of marble was conducted in the The Ruskeala deposits belongs to the Sortavala series end of the 17th century by Swedes, basically for pro- of the Lower Proterozoic and are composed of amphi- duction of construction lime, and less often for building bolites, amphibole and biotite-amphibole schists with foundations and walls in vicinities. http://www.progeo.se NO. 4 2010 Fig. 1. “The Italian quarry”. Photo: M.Vdovets In 1721, after the ending of the Northern war, this terri- It is known, that in the period 1770-1830 there were tory as provided by Peter I decree, was given to private extracted more than 200 thousand tons of marble on possession and populated with peasants from the cen- the site. -

Karelia a Perfect Fit for Your Investment

KARELIA A PERFECT FIT FOR YOUR INVESTMENT 2019 KARELIAINVEST.RU INVEST IN RUSSIA CONTENT Infrastructure for business. Development indicators ............................. 4 Key industries: Forestry .......................................................................................................... 24 Fishery ........................................................................................................... 28 Mining ............................................................................................................ 34 Tourism and recreation ............................................................................... 38 Success stories. Foreign investors in Karelia .......................................... 44 Support of investment activities ................................................................ 54 INFRASTRUCTURE FOR BUSINESS. I DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION Murmansk region SWEDEN Kostomuksha Stockholm 1300 km FINLAND Republic Kem of Karelia Belomorsk Segezha The Baltic Sea Helsinki 740 km Sortavala Kondopoga Tallinn 800 km Petrozavodsk Saint-Petersburg 412 km Riga ESTONIA 990 km Leningrad region LITHANIA LATVIA Vologda region Pskov Novgorod 710 km 510 km Vologda Vilnius Novgorod km 990 km 930 region Pskov Tver region Yaroslavl region region BELARUS Yaroslavl Moscow Tver 1100 kmкм km Minsk 1000 850 km 1300 km OVER 45 MLN. PEOPLE INFRASTRUCTURE FOR BUSINESS live within a 1000 km radius from Petrozavodsk • total area: 180,5 thousand square kilometers; • population: 618,1 thousand people; • -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Eskelinen, Heikki Conference Paper When Intentions Meet Realities: Typology of Contacts across the Finnish-Russian Border 41st Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "European Regional Development Issues in the New Millennium and their Impact on Economic Policy", 29 August - 1 September 2001, Zagreb, Croatia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Eskelinen, Heikki (2001) : When Intentions Meet Realities: Typology of Contacts across the Finnish-Russian Border, 41st Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "European Regional Development Issues in the New Millennium and their Impact on Economic Policy", 29 August - 1 September 2001, Zagreb, Croatia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/115303 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Adamant Holding Book ENG W

Sustainable development from 1992 has assisted the Adamant Holding to become the biggest commercial and production corporation of North-Western Russia. Today the Holding comprises construction divisions, design bureaus, St. Petersburg-biggest network of shopping malls, glass-making factories and many others. High results were achieved thanks to the skills and competences of all workers; currently the company operates in line with the most advanced global practices. We develop our business relations basing on the best traditions of the construction industry combined with 1 our own experience and constant strive for further growth contributing to the success of ourselves and Business Dimensions our partners. www.adamant.ru We are sure in our future, because our confi dence of the Adamant Holding is backed by the glorious history of the Adamant Holding full of notable events, great projects and global accomplishments. I. M. Lejtis TheT President of the Adamant Holding 4 Construction and operation of commercial real estate Shopping malls in operation Shopping malls and business centers under construction Akademicheskiy Balkania NOVA (2nd stage) Atmosphera Continent at Bukharestskaya Aerodrom Continent at Zvezdnaya (2nd stage) Balkania NOVA Mezhdunarodniy Balkanskiy Zanevskiy Kaskad 3 Balkanskiy 1 Skandinavia Baltiyskiy Business Center at Tzvetochnaya Street Warshavskiy Express Business Center at Moika Embankment Zanevskiy Kaskad 1 Business Center at Pobedy Square Zanevskiy Kaskad 2 Zvenigorodskiy Continent at Baikonyrskaya Continent at Zvezdnaya -

Geological Tourism Development in the Finnish-Russian Borderland: the Case of the Cross-Border Geological Route “Mining Road”

Acta Geoturistica volume 9 (2018), number 1, 23-29 doi: 10.1515/agta-2018-0003 Geological Tourism Development In The Finnish-Russian Borderland: The Case Of The Cross-Border Geological Route “Mining Road” 1 2 JARI K. NENONEN AND SVETLANA V. STEPANOVA 1 Geological Survey of Finland, P.O. Box 1237 FI-70211 Kuopio, Finland (e-mail: [email protected]) 2 Institute of Economics, Karelian Research Center, Russian Academy of Sciences, 50, A. Nevskogo Str., Petrozavodsk 185030, Russian Federation (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT The Finnish-Russian borderland has a unique geological potential for geological tourism development. Creating new tourist attractions based on geoheritage, design and development of the cross-border tourist routes open new opportunities for tourism development on both sides of the border. The article presents the cross- border geological tourist route “Mining Road” as a tool of activation of tourist activity in the Finnish-Russian borderland. This article explores the practical aspects of the project "Mining Road" development for tourism industry. It is proven the significance of cross-border route "Mining road" for preservation, popularization and reproduction of the natural, cultural and historical potential of the borderland. Keywords: geotourism, cross-border geological route, “Mining Road”, Finland, Republic of Karelia. INTRODUCTION cooperation in tourism sphere. The relevance of our research is caused With the growing significance of by two factors. On the one side, the environment protection and sustainable Finnish-Russian borderland has unique development the geological tourism is geological resources which can be used not considered as a new perspective direction of only in mining industry but also as a the nature based tourism which can potential for regional development based on contribute to geoheritage conservation and sustainable tourism development. -

Natural Landscapes of Sortavala Archipelago Islands of Northern Part of the Lake Ladoga Artificially-Induced by Old Mining Workings

Hereditas Minariorum, 4, 2017, 123−134 ISSN 2391-9450 (print) ISSN 2450-4114 (online) www.history-of-mining.pwr.wroc.pl DOI: 10.5277/hm170407 Received 27.09.2017; accepted 28.11.2017 NATURAL LANDSCAPES OF SORTAVALA ARCHIPELAGO ISLANDS OF NORTHERN PART OF THE LAKE LADOGA ARTIFICIALLY-INDUCED BY OLD MINING WORKINGS Igor BORISOV The Museum of the North Ladoga, Sortavala, Russian Federation northern Lake Ladoga area, Russia, artificially-induced landscapes, mining workings, mining-industrial heritage Artificially-induced natural landscapes, produced by the interaction of natural processes and mining in the 1770s–1950s, make up a large part of modern landscapes in the northern Lake Ladoga area, Republic of Karelia, Russia. Mine workings have become a common part of modern landscapes in the region. They were formed in various periods of time in various physico-geo- graphic environments and are preserved to a varying degree. Therefore, they are of great interest from the point of view of the evolution of artificially-induced complexes and tourism. Dozens of mining workings in building stone (plagiogranite, gneiss, quartzitic sandstone, amphibolite and marble) and quartz and feldspar sequences, which operated in the 1770s–1930s on Sortavala Archipelago islands (Riekkalansaari, Tu- lolansaari, Vannisen-saari, Leirisaari, Pellotsaari and Kalkkisaari) in Lake Ladoga, were found and studied by the Regional Museum of the Northern Lake Ladoga area (RMLL) in 1993–2016. No human activities are now carried out there. They are now known as artificially-induced natural landscapes (AIL), part of Karelia’s potential and real industrial and geological heritage and tourist attractions. The artificially-induced natural landscapes of Sortavala Archipelago islands in Lake Ladoga are located in the northern part of the Priladozhsky orographic province (skerry zone) in the Northern Ladoga selga mid-taiga district of the West Karelian taiga-lake plain area (selga is a local name of low, long hills). -

Investment Potential of the Republic of Karelia

Investment potential of the Republic of Karelia Igor Titov Deputy Minister of Economic Development and Industry of the Republic of Karelia 1 Karelia – a unique region with beautiful nature 2 2 Republic of Karelia is a part of the North-West federal district of the Russian Federation. Length of land border between Russia and Finland – more than 700 kilometres. • Territory - 180,500 km2 • Resident population – 637 000 • Average population density – 3,5/km2 • Number of people employed in the sphere of economics – 307 000 • 127 municipal entities, including two city districts 3 • Capital – city of Petrozavodsk International border crossing points in the Republic of Karelia IACP Suoperya 5 functional border crossing points: - Inari, - Syuvyaoro, IACP, RBCP Lyuttya - Vyartsilya-Niirala, SCP Inari - Lyuttya-Vartius, - Suoperya-Kuusamo IACP, RBCP Vyartsilya SCP Syuvyaoro 4 Transportation corridors Northern Sea Route The Republic of Karelia is situated at the intersection of active and projected transportation corridors White Sea – Baltic Sea Canal Federal road M18 “Saint Petersburg - Murmansk” Railroad “North - South”, “Saint Petersburg – Murmansk” Republic Euro-Arctic railroad of Karelia “Barents Link” 5 Tourist and recreation potential • There are more than 4000 cultural, historical and natural monuments in Karelia • Among them – unique architectural, cultural and historical items on Kizhi, Valaam and Solovetsky islands • Petroglyphs are ancient rock engravings that remained intact in the Republic of Karelia up to the present moment, having -

Mountain Park «Ruskeala» Is the Pride of Karelia, Located Just in 290 Kilometers from St

Mountain Park «Ruskeala» is the pride of Karelia, located just in 290 kilometers from St. Petersburg. It is an amazing combination of marble mountains, turquoise lakes and lush greenery. While walking around, it is difficult to imagine that just a few centuries ago this place was an adit, where marble was mined under hard conditions. This marble deposit was discovered in the middle of the 17th century. Its development began during the reign of Catherine the Great. The construction of Winter Palace, St. Isaac's Cathedral, Marble Palace and Mikhailovskiy castle required a huge amount of marble and the nearest marble deposit was right here. In the 1980s the adit was closed and nature began to conquer this area. In 2005 it was decided to open the «Ruskeala» marble mountain park on the site of the former adits that was already an ideal place for walks and leisure - quiet and incredibly beautiful. As a result, a convenient walking path appeared around the entire quarry and observation platforms were created in places with the most picturesque panoramas. Guests can find many outdoor activities: excursion routes, diving, boating, bungee jumping, sledding. Extreme sports lovers can either walk along the tightrope over the water surface or ride a 400-meter zip wire stretched right above the canyon. An unforgettable experience and an adrenaline rush are guaranteed. РОО «Золотые Ключи Консьержей», Россия – Les Clefs d’Or Russia ул. Театральный проезд, д. 2 ▪ Москва ▪ 109012 Россия 2 Teatralniy proezd ▪ 109012 Moscow ▪ Russian Federation [email protected] ▪ www.concierge-russia.ru Rowing boats are suitable for those who like a low activity rest or for those who want to feel like a Mediterranean pirate traveling through the grottoes in search of treasures.