Adventive Vertebrates and Historical Ecology in the Pre-Columbian Neotropics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying Gecko Species from Lesser Antillean Paleontological

Identifying Gecko Species from Lesser Antillean Paleontological Assemblages: Intraspecific Osteological Variation within and Interspecific Osteological Differences between Thecadactylus rapicauda (Houttuyn, 1782) (Phyllodactylidae) and Hemidactylus mabouia (Moreau de Jonnès, 1818) (Gekkonidae) Author(s): Corentin Bochaton, Juan D. Daza, and A. Lenoble Source: Journal of Herpetology, 52(3):313-320. Published By: The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles https://doi.org/10.1670/17-093 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1670/17-093 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 52, No. 3, 313–320, 2018 Copyright 2018 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Identifying Gecko Species from Lesser Antillean Paleontological Assemblages: Intraspecific Osteological Variation within and Interspecific Osteological Differences between Thecadactylus rapicauda (Houttuyn, 1782) (Phyllodactylidae) and Hemidactylus mabouia (Moreau de Jonne`s, 1818) (Gekkonidae) 1,2 2 3 CORENTIN BOCHATON, JUAN D. -

The Association of Triatoma Maculata (Ericsson 1848) with the Gecko Thecadactylus Rapicauda (Houttuyn 1782) (Reptilia: Squamata

Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2011; 1(4): 279-284 279 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/apjtb Document heading doi:10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60043-9 襃 2011 by the Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. All rights reserved. The association of Triatoma maculata (Ericsson 1848) with the gecko Thecadactylus rapicauda (Houttuyn 1782) (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae): a strategy of domiciliation of the Chagas disease peridomestic vector in Venezuela? 1 2 1 1 1 1 3 4 Reyes-Lugo M *, Reyes-Contreras M , Salvi I , Gelves W , Avilán A , Llavaneras D , Navarrete LF , Cordero G , Sánchez EE6, Rodríguez-Acosta A3,5 1Medical Entomology Section, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela 2School of Biology, Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas, Venezuela 3Immunochemistry Section, Tropical Medicine Institute, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela 4Tropical Zoology Institute, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela 5Instituto Nacional de Higiene “Rafael Rangel, Caracas, Venezuela 6Texas A&M University-Kingsville, Department of Chemistry, Kingsville, Texas, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Objective: To investigate the bioecological relationship between Chagas disease peridomestic Received 10 March 2011 Methods: I Received in revised form 27 March 2011 vectors and reptiles as source of feeding. n a three-story building, triatomines were 17 2011 captured by direct search and electric vacuum cleaner search in and outside the building. Then, Accepted April Triatoma maculata T. maculata Available online 30 April 2011 age structure of the captured ( ) were identified and recorded. Results: T. maculata Reptiles living in sympatric with the triatomines were also searched. -

Redalyc.PARÁSITOS INTESTINALES DE Thecadactylus Rapicauda

Revista Científica ISSN: 0798-2259 [email protected] Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Cazorla-Perfetti, Dalmiro José; Morales-Moreno, Pedro PARÁSITOS INTESTINALES DE Thecadactylus rapicauda (Reptilia: Squamata, Phyllodactylidae) EN CORO, ESTADO FALCÓN, VENEZUELA Revista Científica, vol. XXV, núm. 4, julio-agosto, 2015, pp. 346-351 Universidad del Zulia Maracaibo, Venezuela Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=95941173011 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto _________________________________________________________________________Revista______________________________________________________________Revista Científica, FCV-LUZ Científica, / Vol. FCV-LUZXXV, N° 4,/ Vol.346-351,2015 XXV, N° 4 PARÁSITOS INTESTINALES DE Thecadactylus rapicauda (Reptilia: Squamata, Phyllodactylidae) EN CORO, ESTADO FALCÓN, VENEZUELA Intestinal Parasites of Thecadactylus rapicauda (Reptilia: Squamata, Phyllodactylidae) in Coro, Falcon State, Venezuela Dalmiro José Cazorla-Perfetti* y Pedro Morales-Moreno Laboratorio de Entomología, Parasitología y Medicina Tropical (L.E.P.A.M.E.T.), Centro de investigaciones Biomédicas (C.I.B.), Universidad Nacional Experimental “Francisco de Miranda”(UNEFM), Estado Falcón, Venezuela. *E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. RESUMEN ABSTRACT -

I. G E O G RAP H IC PA T T E RNS in DIV E RS IT Y a . D Iversity And

I. GEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN DIVERSITY A. Diversity and Endemicty B. Patterns in Mammalian Richness 1 – latitude 2 – area 3 – isolation 4 – elevation C. Hotspots of Mammalian Biodiversity 1 – relevance 2 – optimal characteristics of hotspots 3 – empirical patterns for mammals II. CONSERVATION STATUS OF MAMMALS A. Prehistoric Extinctions B. Historic Extinctions 1 – summary (totals) 2 – taxonomic, morphologic bias 3 – Geographic bias C. Geography of Extinctions 1 – prehistory and human colonization 2 – geographic questions 3 – range collapse in mammals Hotspots of Mammalian Endemicity Endemic Mammals Species Richness (fig. 1) Schipper et al 2009 – Science 322:226. (color pdf distributed to lab sections) Fig. 2. Global patterns of threat, for land (brown) and marine (blue) mammals. (A) Number of globally threatened species (Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Fig. 4. Global patterns of knowledge, for land Endangered). Number of species affected by: (B) habitat loss; (C) harvesting; (D) (terrestrial and freshwater, brown) and marine (blue) accidental mortality; and (E) pollution. Same color scale employed in (B), (C), (D) species. (A) Number of species newly described since and (E) (hence, directly comparable). 1992. (B) Data-Deficient species. Mammal Extinctions 1500 to 2000 (151 species or subspecies; ~ 83 species) COMMON NAME LATIN NAME DATE RANGE PRIMARY CAUSE Lesser Hispanolan Ground Sloth Acratocnus comes 1550 Hispanola introduction of rats and pigs Greater Puerto Rican Ground Sloth Acratocnus major 1500 Puerto Rico introduction of rats -

Investigating Evolutionary Processes Using Ancient and Historical DNA of Rodent Species

Investigating evolutionary processes using ancient and historical DNA of rodent species Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of London Royal Holloway University of London Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX Selina Brace November 2010 1 Declaration I, Selina Brace, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, it is always clearly stated. Selina Brace Ian Barnes 2 “Why should we look to the past? ……Because there is nowhere else to look.” James Burke 3 Abstract The Late Quaternary has been a period of significant change for terrestrial mammals, including episodes of extinction, population sub-division and colonisation. Studying this period provides a means to improve understanding of evolutionary mechanisms, and to determine processes that have led to current distributions. For large mammals, recent work has demonstrated the utility of ancient DNA in understanding demographic change and phylogenetic relationships, largely through well-preserved specimens from permafrost and deep cave deposits. In contrast, much less ancient DNA work has been conducted on small mammals. This project focuses on the development of ancient mitochondrial DNA datasets to explore the utility of rodent ancient DNA analysis. Two studies in Europe investigate population change over millennial timescales. Arctic collared lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus) specimens are chronologically sampled from a single cave locality, Trou Al’Wesse (Belgian Ardennes). Two end Pleistocene population extinction-recolonisation events are identified and correspond temporally with - localised disappearance of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). A second study examines postglacial histories of European water voles (Arvicola), revealing two temporally distinct colonisation events in the UK. -

Bitasion Les Habitations-Plantations Constituent Le Creuset Historique Et Symbolique Où Fut Fondu L’Alliage Original Que Sont Les Cultures Antillaises

Kelly & Bérard Ouvrage dirigé par Bitasion Les habitations-plantations constituent le creuset historique et symbolique où fut fondu l’alliage original que sont les cultures antillaises. Elles sont le berceau des sociétés créoles contemporaines qui y ont puisé tant leur forte parenté que leur Bitasion - Archéologie des habitations-plantations des Petites Antilles diversité. Leur étude a été précocement le terrain de prédilection des historiens. Les archéologues antillanistes se consacraient alors plus volontiers à l’étude des sociétés précolombiennes. Ainsi, en dehors des travaux pionniers de J. Handler et F. Lange à la Barbade, c’est surtout depuis la fin des années 1980 qu’un véritable développement de l’archéologie des habitations-plantations antillaises a pu être observé. Les questions pouvant être traitées par l’archéologie des habitations-plantations sont extrêmement riches et multiples et ne sauraient être épuisées par la publication d’un unique ouvrage. Les différents chapitres qui composent ce livre dirigé par K. Kelly et B. Bérard n’ont pas vocation à tendre à l’exhaustivité. Ils nous semblent, par contre, être représentatifs, par la variété des questions abordée et la diversité des angles d’approche, de la dynamique actuelle de ce champ de la recherche. Cette diversité est évidemment liée à celle des espaces concernés: les habitations-plantations de cinq îles des Petites Antilles : Antigua, la Guadeloupe, la Dominique, la Martinique et la Barbade sont ici étudiées. Elle est aussi, au sein d’un même espace, due à la cohabitation de différentes pratiques universitaires. Nous espérons que cet ouvrage, tout en diffusant une information jusqu’à présent trop dispersée, sera le point de départ de nouveaux travaux. -

Predation of Livestock by Puma (Puma Concolor) and Culpeo Fox (Lycalopex Culpaeus): Numeric and Economic Perspectives Giovana Gallardo, Luis F

www.mastozoologiamexicana.org La Portada La rata chinchilla boliviana (Abrocoma boliviensis) es una de las especies de mamíferos más amenazadas del mundo. Esta foto, resultado de varios años de trabajo de campo, muestra un individuo, posiblemente hembra, siendo presa de un gato de Geoffroy. A. boliviensis fue descrita por William Glanz y Sydney Anderson en 1990, sin embargo, hasta el momento, la información científica sobre la especie es virtualmente inexistente. En este número de THERYA, con artículos dedicados a la memoria del Dr. Sydney Anderson, se presenta un trabajo dedicado a la ecología de A. boliviensis que muestra que todavía hay poblaciones de la especie, al parecer más o menos saludables, en el centro de Bolivia (fotografía: Carmen Julia Quiroga). Nuestro logo “Ozomatli” El nombre de “Ozomatli” proviene del náhuatl se refiere al símbolo astrológico del mono en el calendario azteca, así como al dios de la danza y del fuego. Se relaciona con la alegría, la danza, el canto, las habilidades. Al signo decimoprimero en la cosmogonía mexica. “Ozomatli” es una representación pictórica de los mono arañas (Ateles geoffroyi). La especie de primate de más amplia distribución en México. “ Es habitante de los bosques, sobre todo de los que están por donde sale el sol en Anáhuac. Tiene el dorso pequeño, es barrigudo y su cola, que a veces se enrosca, es larga. Sus manos y sus pies parecen de hombre; también sus uñas. Los Ozomatin gritan y silban y hacen visajes a la gente. Arrojan piedras y palos. Su cara es casi como la de una persona, pero tienen mucho pelo.” THERYA Volumen 11, número 3 septiembre 2020 EDITORIAL La enfermedad hemorrágica viral del conejo impacta a México y amenaza al resto de Latinoamérica Consuelo Lorenzo, Alberto Lafón-Terrazas, Jesús A. -

Ecological Consequences Artificial Night Lighting

Rich Longcore ECOLOGY Advance praise for Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting E c Ecological Consequences “As a kid, I spent many a night under streetlamps looking for toads and bugs, or o l simply watching the bats. The two dozen experts who wrote this text still do. This o of isis aa definitive,definitive, readable,readable, comprehensivecomprehensive reviewreview ofof howhow artificialartificial nightnight lightinglighting affectsaffects g animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of i animals and plants. The reader learns about possible and definite effects of c Artificial Night Lighting photopollution, illustrated with important examples of how to mitigate these effects a on species ranging from sea turtles to moths. Each section is introduced by a l delightful vignette that sends you rushing back to your own nighttime adventures, C be they chasing fireflies or grabbing frogs.” o n —JOHN M. MARZLUFF,, DenmanDenman ProfessorProfessor ofof SustainableSustainable ResourceResource Sciences,Sciences, s College of Forest Resources, University of Washington e q “This book is that rare phenomenon, one that provides us with a unique, relevant, and u seminal contribution to our knowledge, examining the physiological, behavioral, e n reproductive, community,community, and other ecological effectseffects of light pollution. It will c enhance our ability to mitigate this ominous envirenvironmentalonmental alteration thrthroughough mormoree e conscious and effective design of the built environment.” -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their -

Reptile Diversity in an Amazing Tropical Environment: the West Indies - L

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT - Vol. VIII - Reptile Diversity In An Amazing Tropical Environment: The West Indies - L. Rodriguez Schettino REPTILE DIVERSITY IN AN AMAZING TROPICAL ENVIRONMENT: THE WEST INDIES L. Rodriguez Schettino Department of Zoology, Institute of Ecology and Systematics, Cuba To the memory of Ernest E. Williams and Austin Stanley Rand Keywords: Reptiles, West Indies, geographic distribution, morphological and ecological diversity, ecomorphology, threatens, conservation, Cuba Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reptile diversity 2.1. Morphology 2.2.Habitat 3. West Indian reptiles 3.1. Greater Antilles 3.2. Lesser Antilles 3.3. Bahamas 3.4. Cuba (as a study case) 3.4.1. The Species 3.4.2. Geographic and Ecological Distribution 3.4.3. Ecomorphology 3.4.4. Threats and Conservation 4. Conclusions Acknowledgments Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The main features that differentiate “reptiles” from amphibians are their dry scaled tegument andUNESCO their shelled amniotic eggs. In– modern EOLSS studies, birds are classified under the higher category named “Reptilia”, but the term “reptiles” used here does not include birds. One can externally identify at least, three groups of reptiles: turtles, crocodiles, and lizards and snakes. However, all of these three groups are made up by many species that are differentSAMPLE in some morphological characters CHAPTERS like number of scales, color, size, presence or absence of limbs. Also, the habitat use is quite variable; there are reptiles living in almost all the habitats of the Earth, but the majority of the species are only found in the tropical regions of the world. The West Indies is a region of special interest because of its tropical climate, the high number of species living on the islands, the high level of endemism, the high population densities of many species, and the recognized adaptive radiation that has occurred there in some genera, such as Anolis, Sphaerodactylus, and Tropidophis. -

Three New Exotic Gecko Species Identified on Curaçao

Three new exotic gecko species identified on Curaçao By Jocelyn Behm (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Temple University) As part of the Caribbean Island Biogeography were known to have breeding populations it was found in Cuba. It is now present in the While they were processing their genetic samples, meets the Anthropocene project, researchers on Curaçao. Bahamas, Grand Cayman Island, Guadeloupe, and Gerard van Buurt received a notification that the initiated their surveys for exotic reptile and Curaçao. Upon discussions with their collaborator, exotic Tokay gecko (Gekko gecko) was found in the amphibian species on Curaçao. They found three The research team conducted day and evening Gerard van Buurt, he reviewed older photographs Santa Catharina neighborhood of Curaçao. The new exotic gecko species on Curaçao, which surveys island-wide to confirm the presence of and identified a mourning gecko in a photo L’Aldea restaurant has a small display of animals may have negative implications for Curaçao’s these exotic species and potentially identify new taken in 2009. Therefore, they know it has been to entertain visitors including the Tokay gecko, three native gecko species and species. Often exotic species are found more in established on Curaçao for nearly a decade. and apparently juvenile geckos escaped from this native ecosystems. developed areas than natural habitats, so they enclosure and established a breeding population searched both natural areas (e.g., Christoffel, The second species the team discovered is the in the neighborhood. The captive Tokay geckos Exotic species, species introduced to a new Kabouterbos), and developed areas (e.g., resorts, Asian house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus). -

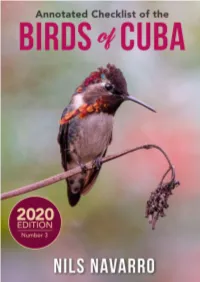

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba.