Ornamentation in Yoruba Domestic Architecture in Osogbo: a Study in Form, Content and Meaning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria Facts

FOUNDED August 28, 1907, in Seattle, USA ESTABLISHED IN Nigeria 1994 WORLD HEADQUARTERS Atlanta, USA ISMEA HEADQUARTERS Dubai, United Arab Emirates NIGERIA HEADQUARTERS Lagos, Nigeria COUNTRY MANAGER Ian Hood WEBSITE www.ups.com COUNTRY WEBSITE ups.com/ng GLOBAL VOLUME & REVENUE 2019 REVENUE $74 billion 2019 DELIVERY VOLUME 5.5 billion packages and documents DAILY DELIVERY VOLUME 21.9 million packages and documents DAILY U.S. AIR VOLUME 3.5 million packages and documents DAILY INTERNATIONAL VOLUME 3.2 million packages and documents EMPLOYEES 297 in Nigeria; 528,000 worldwide BROKERAGE & OPERATING FACILITIES 18 Lagos – Plot 16 Oworonshoki Expressway Gbagada Industrial Estate: Main Operations Center Lagos – LOS Murtala Mohammed International Airport SAHCOL Courier Shed, Ikeja: Brokerage Office Lagos -- 380 Ikorodu Road, Maryland: Warehouse/Supply Chain solutions Aba - Plot 2 Eziukwu Road Aba; Operations Center Abuja (Garki) - Plot 2196 Cadastral Zone A1, Area 3, Beside Savannah Suites; Operations Center Akure - 26 Oyemekun Road; Operations Center Benin - 34 Airport road; Transit Hub & Operations Center Calabar - 65 Ndidem Iso Rd; Operations Center Enugu - 87 Ogui Road; Operations Center Ibadan - 95 Moshood Abiola Way, Ring Rd; Operations Center Jos - 37 Rwam Pam; Operations Center Kaduna – 5 Ali Akilu Road; Transit Hub & Operations Center Kano - 61 Murtala Mohammed Way; Transit Hub & Operations Center Lokoja - KPC 313, Adankolo Junction; Transit Hub & Operations Center Onitsha - 99 Upper New Market; Transit Hub & Operations Center Owerri -

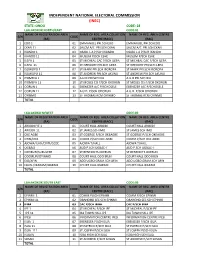

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

A Historical Survey of Socio-Political Administration in Akure Region up to the Contemporary Period

European Scientific Journal August edition vol. 8, No.18 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION IN AKURE REGION UP TO THE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD Afe, Adedayo Emmanuel, PhD Department of Historyand International Studies,AdekunleAjasin University,Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract Thepaper examines the political transformation of Akureregion from the earliest times to the present. The paper traces these stages of political development in order to demonstrate features associated with each stage. It argues further that pre-colonial Akure region, like other Yoruba regions, had a workable political system headed by a monarch. However, the Native Authority Ordinance of 1916, which brought about the establishment of the Native Courts and British judicial administration in the region led to the decline in the political power of the traditional institution.Even after independence, the traditional political institution has continually been subjugated. The work relies on both oral and written sources, which were critically examined. The paper, therefore,argues that even with its present political status in the contemporary Nigerian politics, the traditional political institution is still relevant to the development of thesociety. Keywords: Akure, Political, Social, Traditional and Authority Introduction The paper reviews the political administration ofAkure region from the earliest time to the present and examines the implication of the dynamics between the two periods may have for the future. Thus,assessment of the indigenous political administration, which was prevalent before the incursion of the colonial administration, the political administration during the colonial rule and the present political administration in the region are examined herein.However, Akure, in this context, comprises the present Akure North, Akure South, and Ifedore Local Government Areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA

International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April, May, June 2011 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 Article: 4 ISSN 1309-6249 UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN FACILITIES PROVISION: Ogun State as a Case Study Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA ABSTRACT The Universal Basic Education Programme (UBE) which encompasses primary and junior secondary education for all children (covering the first nine years of schooling), nomadic education and literacy and non-formal education in Nigeria have adopted the “collaborative/partnership approach”. In Ogun State, the UBE Act was passed into law in 2005 after that of the Federal government in 2004, hence, the demonstration of the intention to make the UBE free, compulsory and universal. The aspects of the policy which is capital intensive require the government to provide adequately for basic education in the area of organization, funding, staff development, facilities, among others. With the commencement of the scheme in 1999/2000 until-date, Ogun State, especially in the area of facility provision, has joined in the collaborative effort with the Federal government through counter-part funding to provide some facilities to schools in the State, especially at the Primary level. These facilities include textbooks (in core subjects’ areas- Mathematics, English, Social Studies and Primary Science), blocks of classrooms, furniture, laboratories/library, teachers, etc. This study attempts to assess the level of articulation by the Ogun State Government of its UBE policy within the general framework of the scheme in providing facilities to schools at the primary level. -

As an Expression of Yorùbá Aesthetic Philosophy

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Vol 9 No 4 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Social Sciences July 2018 Research Article © 2018 Ajíbóyè et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Orí (Head) as an Expression of Yorùbá Aesthetic Philosophy Olusegun Ajíbóyè Stephen Fọlárànmí Nanashaitu Umoru-Ọ̀ kẹ Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Obafemi Awólọ́ wọ University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Doi: 10.2478/mjss-2018-0115 Abstract Aesthetics was never a subject or a separate philosophy in the traditional philosophies of black Africa. This is however not a justification to conclude that it is nonexistent. Indeed, aesthetics is a day to day affair among Africans. There are criteria for aesthetic judgment among African societies which vary from one society to the other. The Yorùbá of Southwestern Nigeria are not different. This study sets out to examine how the Yorùbá make their aesthetic judgments and demonstrate their aesthetic philosophy in decorating their orí, which means head among the Yorùbá. The head receives special aesthetic attention because of its spiritual and biological importance. It is an expression of the practicalities of Yorùbá aesthetic values. Literature and field work has been of paramount aid to this study. The study uses photographs, works of art and visual illustrations to show the various ways the head is adorned and cared for among the Yoruba. It relied on Yoruba art and language as a tool of investigating the concept of ori and aesthetics. Yorùbá aesthetic values are practically demonstrable and deeply located in the Yorùbá societal, moral and ethical idealisms. -

The Impact of English Language Proficiency Testing on the Pronunciation Performance of Undergraduates in South-West, Nigeria

Vol. 15(9), pp. 530-535, September, 2020 DOI: 10.5897/ERR2020.4016 Article Number: 2D0D65464669 ISSN: 1990-3839 Copyright ©2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Educational Research and Reviews http://www.academicjournals.org/ERR Full Length Research Paper The impact of English language proficiency testing on the pronunciation performance of undergraduates in South-West, Nigeria Oyinloye Comfort Adebola1*, Adeoye Ayodele1, Fatimayin Foluke2, Osikomaiya M. Olufunke2, and Fatola Olugbenga Lasisi3 1Department of Education, School of Education and Humanities, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria. 2Department of Arts and Social Science, Education Department, Faculty of Education, National Open University of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria. 3Educational Management and Business Studies, Department of Education, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Ogun State, Nigeria. Received 2 June, 2020; Accepted 8 August, 2020 This study investigated the impact of English Language proficiency testing on the pronunciation performance of undergraduates in South-west. Nigeria. The study was a descriptive survey research design. The target population size was 1243 (200-level) undergraduates drawn from eight tertiary institutions. The instruments used for data collection were the English Language Proficiency Test and Pronunciation Test. The English Language proficiency test was used to measure the performance of students in English Language and was adopted from the Post-UTME past questions from Babcock University Admissions Office on Post Unified Tertiary Admissions and Matriculation Examinations screening exercise (Post-UTME) for undergraduates in English and Linguistics. The test contains 20 objective English questions with optional answers. The instruments were validated through experts’ advice as the items in the instrument are considered appropriate in terms of subject content and instructional objectives while Cronbach alpha technique was used to estimate the reliability coefficient of the English Proficiency test, a value of 0.883 was obtained. -

A VISION of WEST AFRICA in the YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study

Millions of inhabitants 10000 West Africa Wor Long-Term Perspective Study 1000 Afr 100 10 1 Yea 1965 1975 1850 1800 1900 1950 1990 2025 2000 Club Saheldu 2020 % of the active population 100 90 80 AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 70 60 50 40 30 NON AGRICULTURAL “INFORMAL” SECTOR 20 10 NON AGRICULTURAL 3MODERN3 SECTOR 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 Preparing for 2020: 6 000 towns of which 300 have more than 100 000 inhabitants Production and total availability in gigaczalories per day Import as a % of availa 500 the Future 450 400 350 300 250 200 A Vision of West Africa 150 100 50 0 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 Imports as a % of availability Total food availability Regional production in the Year 2020 2020 CLUB DU SAHEL PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE A VISION OF WEST AFRICA IN THE YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study Edited by Jean-Marie Cour and Serge Snrech ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ FOREWoRD ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ In 1991, four member countries of the Club du Sahel: Canada, the United States, France and the Netherlands, suggested that a regional study be undertaken of the long-term prospects for West Africa. Several Sahelian countries and several coastal West African countries backed the idea. To carry out this regional study, the Club du Sahel Secretariat and the CINERGIE group (a project set up under a 1991 agreement between the OECD and the African Development Bank) formed a multi-disciplinary team of African and non-African experts. -

When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire Under Historial Review

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo1 1) Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission, Nigeria Date of publication: November 30th, 2014 Edition period: November 2014 – March 2015 To cite this article: Ojo, M.O.D. (2014). When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 248-267. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 No.3 November 2014 pp. 248-267 When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historical Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission Abstract Using historical events research approach and qualitative key informant interview, this study examined how religion failed to stop political crisis that happened in the old Western region of Nigeria. Ikire, in the present Osun State of Nigeria was used as a case study. The study investigated the incidences of killing, arson and exile that characterized the crisis in the town which served as the case study. It argued that the two prominent political figures which started the crisis failed to apply the religious doctrines of love, peace and brotherhood which would have solved the crisis before it spread to all parts of the Old Western Region of Nigeria and the entire nation. -

Ijebu-Ode Ile-Ife Truck Road South- West Nigeria

Ijebu-Ode Ile-Ife Truck Road South- West Nigeria. Client: Federal Ministry of Works Lagos- Nigeria. Location: Osun- Ogun State - Nigeria. Date: 1977 The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Works commissioned Allott (Nigeria) Limited to undertake the location, survey and detailed design of a new trunk road to link the towns of Ijebu Ode Ile-Ife and Sekona which lie to the north of Lagos and south east of Ibadan. The route over which this road was to pass was through thick tropical rain forest and sparsely populated. Access was difficult and the existing dirt roads were impassable in the rainy season. A suitable was located from a study of aerial photography and a ground reconnaissance which was followed by a traverse survey. The detailed design of the road’s alignment was carried out using the latest computer-aided techniques, further to the results of the topographical survey. Other field work Included a hydrological survey and a borehole survey. On completion of the design, the centre line of the new road was staked out by the field team. The proposed road had a two lane carriageway with bituminous surfacing, a crushed stone base and a laterite sub- base. The total length was 140km and there were a total of 13 bridges. The two major structures were the 150m long 6-span bridge over the River Oshun and the 75m long 3-span bridge over the River Shasha. These have in-situ reinforced concrete voided decks supported on reinforced concrete piers. The location of sources of suitable road Construction materials was an important part of the design. -

Nigeria Risk Assessment 2014 INSCT MIDDLE EAST and NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE

INSCT MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AND COUNTERTERRORISM Nigeria Risk Assessment 2014 INSCT MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report—which uses open-source materials such as congressional reports, academic articles, news media accounts, and NGO papers—focuses on three important issues affecting Nigeria’s present and near- term stability: ! Security—key endogenous and exogenous challenges, including Boko Haram and electricity and food shortages. ! The Energy Sector—specifically who owns Nigeria’s mineral resources and how these resources are exploited. ! Defense—an overview of Nigeria’s impressive military capabilities, FIGURE 1: Administrative Map of Nigeria (Nations Online Project). rooted in its colonial past. As Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria is central to the continent’s development, which is why the current security and risk situation is of mounting concern. Nigeria faces many challenges in the 21st century as it tries to accommodate its rising, and very young, population. Its principal security concerns in 2014 and the immediate future are two-fold—threats from Islamist groups, specifically Boko Haram, and from criminal organizations that engage in oil smuggling in the Niger Delta (costing the Nigerian exchequer vast sums of potential oil revenue) and in drug smuggling and human trafficking in the North.1 The presence of these actors has an impact across Nigeria, with the bloody, violent, and frenzied terror campaign of Boko Haram, which is claiming thousands of lives annually, causing a refugee and internal displacement crises. Nigerians increasingly have to seek refuge to avoid Boko Haram and military campaigns against these insurgents. -

Characterization of Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates Obtained from Health Care Institutions in Ekiti and Ondo States, South-Western Nigeria

African Journal of Microbiology Research Vol. 3(12) pp. 962-968 December, 2009 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ajmr ISSN 1996-0808 ©2009 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from health care institutions in Ekiti and Ondo States, South-Western Nigeria Clement Olawale Esan1, Oladiran Famurewa1, 2, Johnson Lin3 and Adebayo Osagie Shittu3, 4* 1Department of Microbiology, University of Ado-Ekiti, P.M.B. 5363, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 2College of Science, Engineering and Technology, Osun State University, P.M.B. 4494, Osogbo, Nigeria 3School of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of KwaZulu-Natal (Westville Campus), Private Bag X54001, Durban, Republic of South Africa. 4Department of Microbiology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Accepted 5 November, 2009 Staphylococcus aureus is one of the major causative agents of infection in all age groups following surgical wounds, skin abscesses, osteomyelitis and septicaemia. In Nigeria, it is one of the most important pathogen and a frequent micro-organism obtained from clinical samples in the microbiology laboratory. Data on clonal identities and diversity, surveillance and new approaches in the molecular epidemiology of this pathogen in Nigeria are limited. This study was conducted for a better understanding on the epidemiology of S. aureus and to enhance therapy and management of patients in Nigeria. A total of 54 S. aureus isolates identified by phenotypic methods and obtained from clinical samples and nasal samples of healthy medical personnel in Ondo and Ekiti States, South-Western Nigeria were analysed. Typing was based on antibiotic susceptibility pattern (antibiotyping), polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphisms (PCR-RFLPs) of the coagulase gene and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).