Effect of Tryptophan Analogs on Derepression of the Escherichia Coli Tryptophan Operon by Indole-3-Propionic Acid Robert J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part One Amino Acids As Building Blocks

Part One Amino Acids as Building Blocks Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins in Organic Chemistry. Vol.3 – Building Blocks, Catalysis and Coupling Chemistry. Edited by Andrew B. Hughes Copyright Ó 2011 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim ISBN: 978-3-527-32102-5 j3 1 Amino Acid Biosynthesis Emily J. Parker and Andrew J. Pratt 1.1 Introduction The ribosomal synthesis of proteins utilizes a family of 20 a-amino acids that are universally coded by the translation machinery; in addition, two further a-amino acids, selenocysteine and pyrrolysine, are now believed to be incorporated into proteins via ribosomal synthesis in some organisms. More than 300 other amino acid residues have been identified in proteins, but most are of restricted distribution and produced via post-translational modification of the ubiquitous protein amino acids [1]. The ribosomally encoded a-amino acids described here ultimately derive from a-keto acids by a process corresponding to reductive amination. The most important biosynthetic distinction relates to whether appropriate carbon skeletons are pre-existing in basic metabolism or whether they have to be synthesized de novo and this division underpins the structure of this chapter. There are a small number of a-keto acids ubiquitously found in core metabolism, notably pyruvate (and a related 3-phosphoglycerate derivative from glycolysis), together with two components of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), oxaloacetate and a-ketoglutarate (a-KG). These building blocks ultimately provide the carbon skeletons for unbranched a-amino acids of three, four, and five carbons, respectively. a-Amino acids with shorter (glycine) or longer (lysine and pyrrolysine) straight chains are made by alternative pathways depending on the available raw materials. -

Yeast Genome Gazetteer P35-65

gazetteer Metabolism 35 tRNA modification mitochondrial transport amino-acid metabolism other tRNA-transcription activities vesicular transport (Golgi network, etc.) nitrogen and sulphur metabolism mRNA synthesis peroxisomal transport nucleotide metabolism mRNA processing (splicing) vacuolar transport phosphate metabolism mRNA processing (5’-end, 3’-end processing extracellular transport carbohydrate metabolism and mRNA degradation) cellular import lipid, fatty-acid and sterol metabolism other mRNA-transcription activities other intracellular-transport activities biosynthesis of vitamins, cofactors and RNA transport prosthetic groups other transcription activities Cellular organization and biogenesis 54 ionic homeostasis organization and biogenesis of cell wall and Protein synthesis 48 plasma membrane Energy 40 ribosomal proteins organization and biogenesis of glycolysis translation (initiation,elongation and cytoskeleton gluconeogenesis termination) organization and biogenesis of endoplasmic pentose-phosphate pathway translational control reticulum and Golgi tricarboxylic-acid pathway tRNA synthetases organization and biogenesis of chromosome respiration other protein-synthesis activities structure fermentation mitochondrial organization and biogenesis metabolism of energy reserves (glycogen Protein destination 49 peroxisomal organization and biogenesis and trehalose) protein folding and stabilization endosomal organization and biogenesis other energy-generation activities protein targeting, sorting and translocation vacuolar and lysosomal -

Genome-Scale Fitness Profile of Caulobacter Crescentus Grown in Natural Freshwater

Supplemental Material Genome-scale fitness profile of Caulobacter crescentus grown in natural freshwater Kristy L. Hentchel, Leila M. Reyes Ruiz, Aretha Fiebig, Patrick D. Curtis, Maureen L. Coleman, Sean Crosson Tn5 and Tn-Himar: comparing gene essentiality and the effects of gene disruption on fitness across studies A previous analysis of a highly saturated Caulobacter Tn5 transposon library revealed a set of genes that are required for growth in complex PYE medium [1]; approximately 14% of genes in the genome were deemed essential. The total genome insertion coverage was lower in the Himar library described here than in the Tn5 dataset of Christen et al (2011), as Tn-Himar inserts specifically into TA dinucleotide sites (with 67% GC content, TA sites are relatively limited in the Caulobacter genome). Genes for which we failed to detect Tn-Himar insertions (Table S13) were largely consistent with essential genes reported by Christen et al [1], with exceptions likely due to differential coverage of Tn5 versus Tn-Himar mutagenesis and differences in metrics used to define essentiality. A comparison of the essential genes defined by Christen et al and by our Tn5-seq and Tn-Himar fitness studies is presented in Table S4. We have uncovered evidence for gene disruptions that both enhanced or reduced strain fitness in lake water and M2X relative to PYE. Such results are consistent for a number of genes across both the Tn5 and Tn-Himar datasets. Disruption of genes encoding three metabolic enzymes, a class C β-lactamase family protein (CCNA_00255), transaldolase (CCNA_03729), and methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase (CCNA_02250), enhanced Caulobacter fitness in Lake Michigan water relative to PYE using both Tn5 and Tn-Himar approaches (Table S7). -

Supplemental Methods

Supplemental Methods: Sample Collection Duplicate surface samples were collected from the Amazon River plume aboard the R/V Knorr in June 2010 (4 52.71’N, 51 21.59’W) during a period of high river discharge. The collection site (Station 10, 4° 52.71’N, 51° 21.59’W; S = 21.0; T = 29.6°C), located ~ 500 Km to the north of the Amazon River mouth, was characterized by the presence of coastal diatoms in the top 8 m of the water column. Sampling was conducted between 0700 and 0900 local time by gently impeller pumping (modified Rule 1800 submersible sump pump) surface water through 10 m of tygon tubing (3 cm) to the ship's deck where it then flowed through a 156 µm mesh into 20 L carboys. In the lab, cells were partitioned into two size fractions by sequential filtration (using a Masterflex peristaltic pump) of the pre-filtered seawater through a 2.0 µm pore-size, 142 mm diameter polycarbonate (PCTE) membrane filter (Sterlitech Corporation, Kent, CWA) and a 0.22 µm pore-size, 142 mm diameter Supor membrane filter (Pall, Port Washington, NY). Metagenomic and non-selective metatranscriptomic analyses were conducted on both pore-size filters; poly(A)-selected (eukaryote-dominated) metatranscriptomic analyses were conducted only on the larger pore-size filter (2.0 µm pore-size). All filters were immediately submerged in RNAlater (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX) in sterile 50 mL conical tubes, incubated at room temperature overnight and then stored at -80oC until extraction. Filtration and stabilization of each sample was completed within 30 min of water collection. -

Nucleophile Specificity in Anthranilate Synthase, Aminodeoxychorismate Synthase, Isochorismate Synthase, and Salicylate Synthase Kristin T

Biochemistry 2010, 49, 2851–2859 2851 DOI: 10.1021/bi100021x Nucleophile Specificity in Anthranilate Synthase, Aminodeoxychorismate Synthase, Isochorismate Synthase, and Salicylate Synthase Kristin T. Ziebart and Michael D. Toney* Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, California 95616 Received January 7, 2010; Revised Manuscript Received February 15, 2010 ABSTRACT: Anthranilate synthase (AS), aminodeoxychorismate synthase (ADCS), isochorismate synthase (IS), and salicylate synthase (SS) are structurally homologous chorismate-utilizing enzymes that carry out the first committed step in the formation of tryptophan, folate, and the siderophores enterobactin and mycobactin, respectively. Each enzyme catalyzes a nucleophilic substitution reaction, but IS and SS are uniquely able to employ water as a nucleophile. Lys147 has been proposed to be the catalytic base that activates water for nucleophilic attack in IS and SS reactions; in AS and ADCS, glutamine occupies the analogous position. To probe the role of Lys147 as a catalytic base, the K147Q IS, K147Q SS, Q147K AS, and Q147K ADCS mutants were prepared and enzyme reactions were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Q147K AS employs water as a nucleophile to a small extent, and the cognate activities of K147Q IS and K147Q SS were reduced ∼25- and ∼50-fold, respectively. Therefore, Lys147 is not solely responsible for activation of water as a nucleophile. Additional factors that contribute to water activation are proposed. A change in substrate preference for K147Q SS pyruvate lyase activity indicates Lys147 partially controls SS reaction specificity. Finally, we demonstrate that AS, ADCS, IS, and SS do not possess choris- mate mutase promiscuous activity, contrary to several previous reports. -

Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia Coli for Natural Product Biosynthesis

Trends in Biotechnology Special Issue: Metabolic Engineering Review Metabolic Engineering of Escherichia coli for Natural Product Biosynthesis Dongsoo Yang,1,4 Seon Young Park,1,4 Yae Seul Park,1 Hyunmin Eun,1 and Sang Yup Lee1,2,3,∗ Natural products are widely employed in our daily lives as food additives, Highlights pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and cosmetic ingredients, among others. E. coli has emerged as a prominent host However, their supply has often been limited because of low-yield extraction for natural product biosynthesis. from natural resources such as plants. To overcome this problem, metabolically Escherichia coli Improved enzymes with higher activity, engineered has emerged as a cell factory for natural product altered substrate specificity, and product biosynthesis because of many advantages including the availability of well- selectivity can be obtained by structure- established tools and strategies for metabolic engineering and high cell density based or computer simulation-based culture, in addition to its high growth rate. We review state-of-the-art metabolic protein engineering. E. coli engineering strategies for enhanced production of natural products in , Balancing the expression levels of genes together with representative examples. Future challenges and prospects of or pathway modules is effective in natural product biosynthesis by engineered E. coli are also discussed. increasing the metabolic flux towards target compounds. E. coli as a Cell Factory for Natural Product Biosynthesis System-wide analysis of metabolic Natural products have been widely used in food and medicine in human history. Many of these networks, omics analysis, adaptive natural products have been developed as pharmaceuticals or employed as structural backbones laboratory evolution, and biosensor- based screening can further increase for the development of new drugs [1], and also as food and cosmetic ingredients. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0102315 A1 Shasky Et Al

US 201601 02315A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0102315 A1 Shasky et al. (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 14, 2016 (54) METHODS FOR PRODUCING Publication Classification POLYPEPTIDES IN ENZYME-DEFICIENT MUTANTS OF FUSARUMVENENTATUM (51) Int. Cl. CI2N 15/80 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: NOVOZYMES, INC., Davis, CA (US) CI2P 2L/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (72) Inventors: Jeffrey Shasky, Davis, CA (US); Wendy CPC ................. CI2N 15/80 (2013.01); C12P21/00 Yoder, Billingshurst (GB) (2013.01) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: NOVOZYMES, INC., Davis, CA (US) The present invention relates to methods of producing a polypeptide, comprising: (a) cultivating a mutant of a parent (21) Appl. No.: 14/974,879 Fusarium venematum strain in a medium for the production of the polypeptide, wherein the mutant strain comprises a poly nucleotide encoding the polypeptide and one or more (sev (22) Filed: Dec. 18, 2015 eral) genes selected from the group consisting of pyrC, amy A, and alpA, wherein the one or more (several) genes are Related U.S. Application Data modified rendering the mutant strain deficient in the produc tion of one or more (several) enzymes selected from the group (63) Continuation of application No. 14/168,766, filed on consisting of orotidine-5'-monophosphate decarboxylase, Jan. 30, 2014, now Pat. No. 9.255,275, which is a alpha-amylase, and alkaline protease, respectively, compared continuation of application No. 13/121.254, filed on to the parent Fusarium venematum strain when cultivated Jun. 1, 2011, now Pat. No. 8,647.856, filed as applica under identical conditions; and (b) recovering the polypep tion No. -

Downloaded From

Veprinskiy et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:36 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-0886-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Assessing in silico the recruitment and functional spectrum of bacterial enzymes from secondary metabolism Valery Veprinskiy2, Leonhard Heizinger1, Maximilian G. Plach1 and Rainer Merkl1* Abstract Background: Microbes, plants, and fungi synthesize an enormous number of metabolites exhibiting rich chemical diversity. For a high-level classification, metabolism is subdivided into primary (PM) and secondary (SM) metabolism. SM products are often not essential for survival of the organism and it is generally assumed that SM enzymes stem from PM homologs. Results: We wanted to assess evolutionary relationships and function of bona fide bacterial PM and SM enzymes. Thus, we analyzed the content of 1010 biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from the MIBiG dataset; the encoded bacterial enzymes served as representatives of SM. The content of 15 bacterial genomes known not to harbor BGCs served as a representation of PM. Enzymes were categorized on their EC number and for these enzyme functions, frequencies were determined. The comparison of PM/SM frequencies indicates a certain preference for hydrolases (EC class 3) and ligases (EC class 6) in PM and of oxidoreductases (EC class 1) and lyases (EC class 4) in SM. Based on BLAST searches, we determined pairs of PM/SM homologs and their functional diversity. Oxidoreductases, transferases (EC class 2), lyases and isomerases (EC class 5) form a tightly interlinked network indicating that many protein folds can accommodate different functions in PM and SM. In contrast, the functional diversity of hydrolases and especially ligases is significantly limited in PM and SM. -

1 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1 2 an Archaeal Symbiont

1 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 2 3 An archaeal symbiont-host association from the deep terrestrial subsurface 4 5 Katrin Schwank1, Till L. V. Bornemann1, Nina Dombrowski2, Anja Spang2,3, Jillian F. Banfield4 and 6 Alexander J. Probst1* 7 8 9 1 Group for Aquatic Microbial Ecology (GAME), Biofilm Center, Department of Chemistry, 10 University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany 11 2Department of Marine Microbiology and Biogeochemistry (MMB), Royal Netherlands Institute 12 for Sea Research (NIOZ), and Utrecht University, Den Burg, Netherlands 13 3Department of Cell- and Molecular Biology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala University, SE- 14 75123, Uppsala, Sweden 15 4 Department for Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, USA 16 17 *to whom the correspondence should be addressed: 18 Alexander J. Probst 19 University of Duisburg-Essen 20 Universitätsstrasse 4 21 45141 Essen 22 [email protected] 23 24 25 Content: 26 1. Supplementary Methods 27 2. Supplementary Tables 28 3. Supplementary Figure 29 4. References 30 31 32 33 1. Supplementary methods 34 Phylogenetic analysis 35 Hmm profiles of the 37 maker genes used by the phylosift v1.01 software [1, 2] were queried 36 against a representative set of archaeal genomes from NCBI (182) and the GOLD database (3) as 37 well as against the huberarchaeal population genome (for details on genomes please see 38 Supplementary Data file 1) using the phylosift search mode [1, 2]. Protein sequences 39 corresponding to each of the maker genes were subsequently aligned using mafft-linsi v7.407 [3] 40 and trimmed with BMGE-1.12 (parameters: -t AA -m BLOSUM30 -h 0.55) [4]. -

Induction of Anthranilate Synthase Activity by Elicitors in Oats

Induction of Anthranilate Synthase Activity by Elicitors in Oats Tetsuya Matsukawaa,b,*, Atsushi Ishiharaa,b and Hajime Iwamurab,c a Division of Applied Life Sciences, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan. Fax: +81(75) 7536408. E-mail: [email protected] b CREST, Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST) c Department of Bio-Technology, School of Biology-Oriented Science and Technology, Kinki University, Uchita-cho, Naga-gun, Wakayama 649-6493, Japan * Author for correspondence and reprint requests Z. Naturforsch. 57c, 121Ð128 (2002); received September 10/October 12, 2001 Anthranilate Synthase, Avenanthramide, Oats Oat phytoalexins, avenanthramides, are a series of substituted hydroxycinnamic acid am- ides with anthranilate. The anthranilate in avenanthramides is biosynthesized by anthranilate synthase (AS, EC 4.1.3.27). Induction of anthranilate synthase activity was investigated in oat leaves treated with oligo-N-acetylchitooligosaccharide elicitors. AS activity increased transiently, peaking 6 h after the elicitation. The induction of activity was dependent on the concentration and the degree of polymerization of the oligo-N-acetylchitooligosaccharide elicitor. These findings indicate that the induction is part of a concerted biochemical change required for avenanthramide production. The elicitor-inducible AS activity was strongly in- hibited by l-tryptophan and its analogues including 5-methyl-dl-tryptophan, and 5- and 6- fluoro-dl-tryptophan, while the activity was not affected by d-tryptophan. The accumulation of avenanthramide A was also inhibited by treatment of elicited leaves with these AS inhibi- tors, indicating that a feedback-sensitive AS is responsible for the avenanthramide pro- duction. In elicited leaves, the content of free anthranilate remained at a steady, low level during avenanthramide production. -

Suppression of Chorismate Synthase, Which Is Localized in Chloroplasts

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Suppression of chorismate synthase, which is localized in chloroplasts and peroxisomes, results in abnormal fower development and anthocyanin reduction in petunia Shiwei Zhong1,2, Zeyu Chen1, Jinyi Han1, Huina Zhao3, Juanxu Liu1 & Yixun Yu 1,2* In plants, the shikimate pathway generally occurs in plastids and leads to the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids. Chorismate synthase (CS) catalyses the last step of the conversion of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate (EPSP) to chorismate, but the role of CS in the metabolism of higher plants has not been reported. In this study, we found that PhCS, which is encoded by a single- copy gene in petunia (Petunia hybrida), contains N-terminal plastidic transit peptides and peroxisomal targeting signals. Green fuorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein assays revealed that PhCS was localized in chloroplasts and, unexpectedly, in peroxisomes. Petunia plants with reduced PhCS activity were generated through virus-induced gene silencing and further characterized. PhCS silencing resulted in reduced CS activity, severe growth retardation, abnormal fower and leaf development and reduced levels of folate and pigments, including chlorophylls, carotenoids and anthocyanins. A widely targeted metabolomics analysis showed that most primary and secondary metabolites were signifcantly changed in pTRV2-PhCS-treated corollas. Overall, the results revealed a clear connection between primary and specialized metabolism related to the shikimate pathway in petunia. Te shikimate pathway -

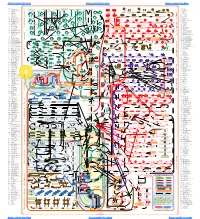

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc.