Sprache Und Geschichte in Afrika

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Peace Is Not Peaceful : Violence Against Women in the Central African Republic

The programme ‘Empowering Women for Sustainable Development’ of the European Union in the Central African Republic When Peace is not Peaceful : Violence against Women in the Central African Republic Results of a Baseline Study on Perceptions and Rates of Incidence of Violence against Women This project is financed by the The project is implemented by Mercy European Union Corps in partnership with the Central African Women’s Organisation When Peace is not Peaceful: Violence Against Women in the Central African Republic Report of results from a baseline study on perceptions of women’s rights and incidence of violence against women — Executive Summary — Mercy Corps Central African Republic is currently implementing a two-year project funded by the European Commission, in partnership with the Organization of Central African Women, to empower women to become active participants in the country’s development. The program has the following objectives: to build the capacities of local women’s associations to contribute to their own development and to become active members of civil society; and to raise awareness amongst both men and women of laws protecting women’s rights and to change attitudes regarding violence against women. The project is being conducted in the four zones of Bangui, Bouar, Bambari and Bangassou. For many women in the Central African Republic, violence is a reality of daily life. In recent years, much attention has been focused on the humanitarian crisis in the north, where a February 2007 study conducted by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs highlighted the horrific problem of violence against women in conflict-affected areas, finding that 15% of women had been victims of sexual violence. -

089 La Politique Idigene in the History of Bangui.Pdf

La polit...iq,u:e indigene in t...he history o£ Bangui William J. Samarin impatltntly awaiting tht day when 1 Centrlllfricu one wHI bt written. But it must bt 1 history, 1 rtlltned argument biSed 01 Peaceful beginnings carefully sifted fact. Fiction, not without its own role, ciMot be No other outpost of' European allowtd to rtplace nor be confused with history. I mm ne colonization in central Africa seems to have atttmpt at 1 gentral history of the post, ner do I inttgratt, had such a troubled history as that of' except in 1 small way, the history of Zongo, 1 post of the Conge Bangui, founded by the French in June 1889. Frte State just across tht river ud foundtd around the nme Its first ten or fifteen years, as reported by timt. Chronolo;cal dttlils regarding tht foundation of B~ngui ll't the whites who lived them, were dangerous to be found in Cantoumt (1986),] and uncertain, if' not desperate) ones. For a 1 time there was even talk of' abandoning the The selection of' the site for the post. that. Albert Dolisie named Bangui was undoubtedly post or founding a more important one a little further up the Ubangi River. The main a rational one. This place was not, to beiin problem was that of' relations with the local with, at far remove from the last. post at. Modzaka; it. was crucial in those years to be people •. The purpose of' the present study is able to communicate from one post to to describe this turbulent period in Bangui's another reasonably well by canoe as well as history and attempt to explain it. -

Wr:X3,Clti: Lilelir)

ti:_Lilelir) 1^ (Dr\ wr:x3,cL KONINKLIJK MUSEUM MUSEE ROYAL DE VOOR MIDDEN-AFRIKA L'AFRIQUE CENTRALE TERVUREN, BELGIË TERVUREN, BELGIQUE INVENTARIS VAN INVENTAIRE DES HET HISTORISCH ARCHIEF VOL. 8 ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES LA MÉMOIRE DES BELGES EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE INVENTAIRE DES ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES PRIVÉES DU MUSÉE ROYAL DE L'AFRIQUE CENTRALE DE 1858 À NOS JOURS par Patricia VAN SCHUYLENBERGH Sous la direction de Philippe MARECHAL 1997 Cet ouvrage a été réalisé dans le cadre du programme "Centres de services et réseaux de recherche" pour le compte de l'Etat belge, Services fédéraux des affaires scientifiques, techniques et culturelles (Services du Premier Ministre) ISBN 2-87398-006-0 D/1997/0254/07 Photos de couverture: Recto: Maurice CALMEYN, au 2ème campement en . face de Bima, du 28 juin au 12 juillet 1907. Verso: extrait de son journal de notes, 12 juin 1908. M.R.A.C., Hist., 62.31.1. © AFRICA-MUSEUM (Tervuren, Belgium) INTRODUCTION La réalisation d'un inventaire des papiers de l'Etat ou de la colonie, missionnaires, privés de la section Histoire de la Présence ingénieurs, botanistes, géologues, artistes, belge Outre-Mer s'inscrit dans touristes, etc. - de leur famille ou de leurs l'aboutissement du projet "Centres de descendants et qui illustrent de manière services et réseaux de recherche", financé par extrêmement variée, l'histoire de la présence les Services fédéraux des affaires belge - et européenne- en Afrique centrale. scientifiques, techniques et culturelles, visant Quelques autres centres de documentation à rassembler sur une banque de données comme les Archives Générales du Royaume, informatisée, des témoignages écrits sur la le Musée royal de l'Armée et d'Histoire présence belge dans le monde et a fortiori, en militaire, les congrégations religieuses ou, à Afrique centrale, destination privilégiée de la une moindre échelle, les Archives Africaines plupart des Belges qui partaient à l'étranger. -

Central African Republic: Sectarian and Inter-Communal Violence Continues

THE WAR REPORT 2018 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC: SECTARIAN AND INTER-COMMUNAL VIOLENCE CONTINUES © ICRC JANUARY 2019 I GIULIA MARCUCCI THE GENEVA ACADEMY A JOINT CENTER OF Furthermore, it provided that Bozizé would remain in HISTORY OF THE CONFLICT power until 2016 but could not run for a third term. The current violence in the Central African Republic However, the Libreville Agreement was mainly (CAR), often referred to as the ‘forgotten’ conflict, has its negotiated by regional heads of state while the leaders of most recent roots in 2013, when the warring parties in CAR and Muslim rebels from the Seleka The current violence in the Central the African Union (AU) itself umbrella group organized a African Republic (CAR), often played a marginal role.4 Thus, coup d’état seizing power in a referred to as the ‘forgotten’ conflict, its actual implementation Christian-majority country.1 has its most recent roots in 2013, immediately proved to be a From the end of 2012 to the when Muslim rebels from the Seleka failure and the reforms required beginning of 2013, the Seleka umbrella group organized a coup under the transition were coalition, mainly composed d’état seizing power in a Christian- never undertaken by Bozizé’s of armed groups from north- majority country. government.5 This generated eastern CAR, including the frustration within the Seleka Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR), Democratic coalition, which decided to take action and, by 24 March Front of the Central African People (FDPC), the Patriotic 2013, gained control over Bangui and 15 of the country’s Convention for the Country’s Salvation (CPSK) and 16 provinces. -

Exploratory Trip to Democratic Republic of the Congo, August 20 – September 15, 2004

Exploratory Trip to Democratic Republic of the Congo, August 20 – September 15, 2004 Trip Report for International Programs Office, USDA Forest Service, Washington, D.C. Final version: December 15, 2004 Bruce G. Marcot, USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station, 620 S.W. Main St., Suite 400, Portland, Oregon 97205, 503-808-2010, [email protected] Rick Alexander, USDA Forest Service Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region, 1323 Club Dr., Vallejo CA 94592, 707 562-9014, [email protected] CONTENTS 1 Summary ……………………………………………………………………………………… 4 2 Introduction and Setting ………………………………………………………….…………… 5 3 Terms of Reference ……………………….…………………...……………………………… 5 4 Team Members and Contacts ………………………………………………….……………… 6 5 Team Schedule and Itinerary …………………………………………..….………...………… 6 6 Challenges to Community Forestry ...…………………………………………….…………… 7 6.1 Use of Community Options and Investment Tools (COAIT) ……………………… 7 6.2 Feasibility and Desirability of Lac Tumba Communities Engaging in Sustainable Timber Harvesting ..……………………………………….….…… 10 7 Conclusions, Recommendations, and Opportunities ..………………………...……………... 15 7.1 Overall Conclusions ...……………………………………………….………….…. 15 7.2 Recommendations …………………………………………………….…………… 19 7.2.1 Potential further involvement by FS .…………………………...………. 19 7.2.2 Aiding village communities under the IRM COAIT process .………..… 20 7.2.3 IRM’s community forest management program ..…………………...….. 23 7.2.4 USAID and CARPE .………………………………………….………… 26 7.2.5 Implementation Decrees under the 2002 Forestry Code ……………….. 28 8 Specific Observations ..……………………………………………...…………………….…. 32 8.1 Wildlife and Biodiversity …………………………………………..……………… 32 8.1.1 Endangered wildlife and the bushmeat trade .………………………..…. 32 8.1.2 Wildlife of young and old forests .…………………………………...…. 34 8.1.3 Forest trees and their associations .………………………………….….. 37 8.1.4 Caterpillars and trees .……………………………………………….….. 38 8.1.5 Islands and trees …………………………………………………….….. 39 8.1.6 Army ants ………………..………………………….…………………. -

The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining

Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. The main road west of Bambari toward Bria and the Mouka-Ouadda plateau, Central African Republic, 2006. Photograph by Peter Chirico, U.S. Geological Survey. The Central African Republic Diamond Database—A Geodatabase of Archival Diamond Occurrences and Areas of Recent Artisanal and Small-Scale Diamond Mining By Jessica D. DeWitt, Peter G. Chirico, Sarah E. Bergstresser, and Inga E. Clark Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development under the auspices of the U.S. Department of State Open-File Report 2018–1088 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey James F. Reilly II, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2018 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Central African Republic: Who Has a Sub-Office/Base Where? (05 May 2014)

Central African Republic: Who has a Sub-Office/Base where? (05 May 2014) LEGEND DRC IRC DRC Sub-office or base location Coopi MSF-E SCI MSF-E SUDAN DRC Solidarités ICRC ICDI United Nations Agency PU-AMI MENTOR CRCA TGH DRC LWF Red Cross and Red Crescent MSF-F MENTOR OCHA IMC Movement ICRC Birao CRCA UNHCR ICRC MSF-E CRCA International Non-Governmental OCHA UNICEF Organization (NGO) Sikikédé UNHCR CHAD WFP ACF IMC UNDSS UNDSS Tiringoulou CRS TGH WFP UNFPA ICRC Coopi MFS-H WHO Ouanda-Djallé MSF-H DRC IMC SFCG SOUTH FCA DRC Ndélé IMC SUDAN IRC Sam-Ouandja War Child MSF-F SOS VdE Ouadda Coopi Coopi CRCA Ngaounday IMC Markounda Kabo ICRC OCHA MSF-F UNHCR Paoua Batangafo Kaga-Bandoro Koui Boguila UNICEF Bocaranga TGH Coopi Mbrès Bria WFP Bouca SCI CRS INVISIBLE FAO Bossangoa MSF-H CHILDREN UNDSS Bozoum COHEB Grimari Bakouma SCI UNFPA Sibut Bambari Bouar SFCG Yaloké Mboki ACTED Bossembélé ICRC MSF-F ACF Obo Cordaid Alindao Zémio CRCA SCI Rafaï MSF-F Bangassou Carnot ACTED Cordaid Bangui* ALIMA ACTED Berbérati Boda Mobaye Coopi CRS Coopi DRC Bimbo EMERGENCY Ouango COHEB Mercy Corps Mercy Corps CRS FCA Mbaïki ACF Cordaid SCI SCI IMC Batalimo CRS Mercy Corps TGH MSF-H Nola COHEB Mercy Corps SFCG MSF-CH IMC SFCG COOPI SCI MSF-B ICRC SCI MSF-H ICRC ICDI CRS SCI CRCA ACF COOPI ICRC UNHCR IMC AHA WFP UNHCR AHA CRF UNDSS MSF-CH OIM UNDSS COHEB OCHA WFP FAO ACTED DEMOCRATIC WHO PU-AMI UNHCR UNDSS WHO CRF MSF-H MSF-B UNFPA REPUBLIC UNICEF UNICEF 50km *More than 50 humanitarian organizations work in the CAR with an office in Bangui. -

Living Under a Fluctuating Climate and a Drying Congo Basin

sustainability Article Living under a Fluctuating Climate and a Drying Congo Basin Denis Jean Sonwa 1,* , Mfochivé Oumarou Farikou 2, Gapia Martial 3 and Fiyo Losembe Félix 4 1 Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Yaoundé P. O. Box 2008 Messa, Cameroon 2 Department of Earth Science, University of Yaoundé 1, Yaoundé P. O. Box 812, Cameroon; [email protected] 3 Higher Institute of Rural Development (ISDR of Mbaïki), University of Bangui, Bangui P. O. Box 1450, Central African Republic (CAR); [email protected] 4 Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources Management, University of Kisangani, Kisangani P. O. Box 2012, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 December 2019; Accepted: 20 March 2020; Published: 7 April 2020 Abstract: Humid conditions and equatorial forest in the Congo Basin have allowed for the maintenance of significant biodiversity and carbon stock. The ecological services and products of this forest are of high importance, particularly for smallholders living in forest landscapes and watersheds. Unfortunately, in addition to deforestation and forest degradation, climate change/variability are impacting this region, including both forests and populations. We developed three case studies based on field observations in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as information from the literature. Our key findings are: (1) the forest-related water cycle of the Congo Basin is not stable, and is gradually changing; (2) climate change is impacting the water cycle of the basin; and, (3) the slow modification of the water cycle is affecting livelihoods in the Congo Basin. -

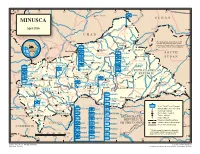

MINUSCA T a Ou M L B U a a O L H R a R S H Birao E a L April 2016 R B Al Fifi 'A 10 H R 10 ° a a ° B B C H a VAKAGA R I CHAD

14° 16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° ZAMBIA Am Timan é Aoukal SUDAN MINUSCA t a ou m l B u a a O l h a r r S h Birao e a l April 2016 r B Al Fifi 'A 10 h r 10 ° a a ° B b C h a VAKAGA r i CHAD Sarh Garba The boundaries and names shown ouk ahr A Ouanda and the designations used on this B Djallé map do not imply official endorsement Doba HQ Sector Center or acceptance by the United Nations. CENTRAL AFRICAN Sam Ouandja Ndélé K REPUBLIC Maïkouma PAKISTAN o t t SOUTH BAMINGUI HQ Sector East o BANGORAN 8 BANGLADESH Kaouadja 8° ° SUDAN Goré i MOROCCO u a g n i n i Kabo n BANGLADESH i V i u HAUTE-KOTTO b b g BENIN i Markounda i Bamingui n r r i Sector G Batangafo G PAKISTAN m Paoua a CAMBODIA HQ Sector West B EAST CAMEROON Kaga Bandoro Yangalia RWANDA CENTRAL AFRICAN BANGLADESH m a NANA Mbrès h OUAKA REPUBLIC OUHAM u GRÉBIZI HAUT- O ka Bria Yalinga Bossangoa o NIGER -PENDÉ a k MBOMOU Bouca u n Dékoa MAURITANIA i O h Bozoum C FPU CAMEROON 1 OUHAM Ippy i 6 BURUNDI Sector r Djéma 6 ° a ° Bambari b ra Bouar CENTER M Ouar Baoro Sector Sibut Baboua Grimari Bakouma NANA-MAMBÉRÉ KÉMO- BASSE MBOMOU M WEST Obo a Yaloke KOTTO m Bossembélé GRIBINGUI M b angúi bo er ub FPU BURUNDI 1 mo e OMBELLA-MPOKOYaloke Zémio u O Rafaï Boali Kouango Carnot L Bangassou o FPU BURUNDI 2 MAMBÉRÉ b a y -KADEI CONGO e Bangui Boda FPU CAMEROON 2 Berberati Ouango JTB Joint Task Force Bangui LOBAYE i Gamboula FORCE HQ FPU CONGO Miltary Observer Position 4 Kade HQ EGYPT 4° ° Mbaïki Uele National Capital SANGHA Bondo Mongoumba JTB INDONESIA FPU MAURITANIA Préfecture Capital Yokadouma Tomori Nola Town, Village DEMOCRATICDEMOCRATIC Major Airport MBAÉRÉ UNPOL PAKISTAN PSU RWANDA REPUBLICREPUBLIC International Boundary Salo i Titule g Undetermined Boundary* CONGO n EGYPT PERU OFOF THE THE CONGO CONGO a FPU RWANDA 1 a Préfecture Boundary h b g CAMEROON U Buta n GABON SENEGAL a gala FPU RWANDA 2 S n o M * Final boundary between the Republic RWANDA SERBIA Bumba of the Sudan and the Republic of South 0 50 100 150 200 250 km FPU SENEGAL Sudan has not yet been determined. -

Siluriformes: Amphiliidae) from the Congo River Basin, the Sister-Group to All Other Genera of the Doumeinae, with the Description of Two New Species

A New Genus of African Loach Catfish (Siluriformes: Amphiliidae) from the Congo River Basin, the Sister-Group to All Other Genera of the Doumeinae, with the Description of Two New Species Carl J. Ferraris, Jr.1, Richard P. Vari2, and Paul H. Skelton3 Copeia 2011, No. 4, 477–489 A New Genus of African Loach Catfish (Siluriformes: Amphiliidae) from the Congo River Basin, the Sister-Group to All Other Genera of the Doumeinae, with the Description of Two New Species Carl J. Ferraris, Jr.1, Richard P. Vari2, and Paul H. Skelton3 Congo River basin catfishes previously identified as Doumea alula (Amphiliidae, Doumeinae) were found to include three species that belong not to the genus Doumea but are, instead, the sister-group to a clade formed by all remaining Doumeinae. The species are assigned to a new genus, Congoglanis. Characters delimiting the Doumeinae and the clade consisting of all members of the subfamily except Congoglanis are detailed. Congoglanis alula is distributed throughout much of the Congo River basin; C. inga, new species, is known only from the lower Congo River in the vicinity of Inga Rapids; and C. sagitta, new species, occurs in the Lualaba River basin of Zambia in the southeastern portion of the Congo River system. ATFISHES of the subfamily Doumeinae of the Congoglanis, new genus Amphiliidae inhabit rapidly flowing rivers and Type species.—Congoglanis inga, new species C streams across a broad expanse of tropical Africa. Recent studies of the Doumeinae documented that the Diagnosis.—Congoglanis includes species that possess the species diversity and morphological variability within the following combination of characters unique within the subfamily are greater than previously suspected (Ferraris Amphiliidae: the caudal peduncle is relatively short and et al., 2010). -

HA.01.0015 Inventaire Des Archives De Frédéric Orban

HA.01.0015 Inventaire des archives de Frédéric Orban 1857 – 1883 Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Afrika Tervuren, 2016 Description des archives Nom: Archives Frédéric Orban Référence: HA.01.0015 Dates extrêmes: 1881-1884, 1932 Importance matérielle: 0,23 m.l. Langues des pièces: Les documents sont rédigés en Français pour la majeure partie. Lieu de conservation: Musée royal de l'Afrique Centrale Historique de la conservation : Don au MRAC de M. Deborsu en 1929 et de M. De Suray en 1932 Context Le Producteur d'archives Frédéric Orban est né le 3 mars 1857 à Emptinne (Belgique). Sorti de l’École militaire en 1877 avec le grade de sous-lieutenant, il demande à être détaché à l’Institut cartographique militaire en 1881. C’est le 17 février de cette année-là que Frédéric Orban part en Afrique pour le compte du Comité d’études du Haut-Congo, en compagnie d’Eugène Janssen. Ils parviennent à Vivi en avril et y retrouvent Valcke. Bientôt ils sont chargés de superviser les travaux du poste d’Isanghila. En décembre 1881, Orban et Callewaert se voient confier la mission de transporter les pièces du nouveau vapeur l’AIA par voie de terre jusqu’à Léopoldville. C’est chose fait en mars 1882. Quand en novembre 1882, Hanssens fonde le poste de Bolobo, Orban est commissionné pour prendre la direction de la station. Mais sa mauvaise santé l’oblige à quitter ses fonctions en mars 1883. Il envisageait d’aller se rétablir au sanatorium de Banana mais en chemin il rencontre Stanley qui le charge de se rendre à Vivi puis au Pool avec un lot important de marchandises d’échange destinées au Haut-Congo. -

Aspects of Multilingualism in the Democratic Republic of the Congo!

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio da Universidade da Coruña Aspects of Multilingualism in the Democratic Republic of the Congo! Helena Lopez Palma [email protected] Abstract The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a multilingual country where 214 native languages (Ethnologue) are spoken among circa 68 million inhabitants (2008). The situations derived from the practice of a multilingual mode of communication have had important linguistic effects on the languages in contact. Those have been particularly crucial in the rural areas, where the relations between the individual speakers of different micro linguistic groups have contributed to varied degrees of modification of the grammatical code of the languages. The contact that resulted from migratory movements could also explain why some linguistic features (i.e. logophoricity, Güldemann 2003) are shared by genetically diverse languages spoken across a large macro-area. The coexistence of such a large number of languages in the DRC has important cultural, economical, sanitary and political effects on the life of the Congolese people, who could be crucially affected by the decisions on language policy taken by the Administration. Keywords: Multilingualism, languages in contact, Central-Sudanic, Adamawa-Ubangian, Bantoid, language policy 1. Introduction This paper addresses the multilingual situation currently found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The word ‘multilingualism’ may be used to refer to the linguistic skill of any individual who is able to use with equal competency various different languages in some interlinguistic communicative situation. It may also be used to refer to the linguistic situation of a country where several different languages coexist.