Testing the Military Flyer at Fort Myer, 1908-1909

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn 2018, Vol

www.telcomhistory.org (303) 296‐1221 Autumn 2018, Vol. 23, no.3 Jody Georgeson, editor A Message from Our Director As I write this, Summer is coming to a close and you can feel the change of the seasons in the air. Kids are going Back to school, nights are getting cooler, leaves are starting to turn and soon our days will Be filled with holiday celeBrations. We have a lot to Be thankful for. We had a great celeBration in July at our Seattle Connections Museum. Visitors joined us from near and far for our Open House. We are grateful to all the volunteers and Seattle Board memBers for their hard work and dedication in making this a successful event. Be sure to read more about the new exhiBit that was dedicated in honor of our late Seattle curator, Don Ostrand, in this issue. I would also like to thank our partners at Telephone Collectors International (TCI) and JKL Museum who traveled from California to help us celeBrate. As always, we welcome anyone who wants to visit either of our locations or to volunteer to help preserve the history of the telecommunications industry. Visit our website at www.telcomhistory.org for more information. Enjoy the remainder of 2018. Warm regards, Lisa Berquist Executive Director Ostrand Collection Ribbon-cutting at Connections Museum Seattle! By Dave Dintenfass A special riBBon-cutting celeBration took place on 14 July 2018 at Connections Museum Seattle. This marked the opening of a special room to display the Ostrand Collection. This collection, on loan from the family of our late curator Don Ostrand, contains unusual items not featured elsewhere in our museum. -

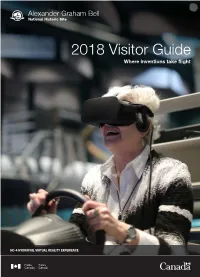

2018 Visitor Guide Where Inventions Take flight

2018 Visitor Guide Where inventions take flight HD-4 HYDROFOIL VIRTUAL REALITY EXPERIENCE How to reach us Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site 559 Chebucto St (Route 205) Baddeck, Nova Scotia Canada 902-295-2069 [email protected] parkscanada.gc.ca/bell Follow us Welcome to Alexander Graham Bell /AGBNHS National Historic Site @ParksCanada_NS Imagine when travel and global communications as we know them were just a dream. How did we move from that reality to @parks.canada one where communication is instantaneous and globetrotting is an everyday event? Alexander Graham Bell was a communication and transportation pioneer, as well as a teacher, family man and humanitarian. /ParksCanadaAgency Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site is an architecturally unique exhibit complex where models, replicas, photo displays, artifacts and films describe the fascinating life and work of Alexander Hours of operation Graham Bell. Programs such as our White Glove Tours complement May 18 – October 30, 2018 the exhibits at the site, which is situated on ten hectares of land 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. overlooking Baddeck Bay and Beinn Bhreagh peninsula, the location of the Bells’ summer home. Entrance fees In the words of Bell, a born inventor Adult: $7.80 “Wealth and fame are coveted by all men, but the hope of wealth or the desire for fame will never make an inventor…you may take away all that he has, Senior: $6.55 and he will go on inventing. He can no more help inventing than he can help Youth: free thinking or breathing. Inventors are born — not made.” — Alexander Graham Bell Starting January 1, 2018, admission to all Parks Canada places for youth 17 and under is free! There’s no better time to create lasting memories with the whole family. -

Jerome S. Fanciulli Collection History of Aviation Collection

Jerome S. Fanciulli Collection History of Aviation Collection Provenance Jerome S. Fanciulli was born in New York City, January 12, 1988. He was the son of Professor Francesco and Amanda Fanciulli. He was educated at de Witt Clinton High School in New York City. He attended St. Louis University, St. Louis, 1903-04 and Stevens Institute, Hoboken, N.J., 1904-05. He married Marian Callaghan in November, 1909. On January 12, 1986 he died in Winchester Hospital in Winchester, Virginia. Mr. Fanciulli worked for the Washington Post and then joined the Associated Press where his assignments were on the Capitol staff of the Associated Press. He became the AP’s aviation specialist. Mr. Fanciulli was a charter member of the National Press Club and a founding member of the Aero Club of Washington, D.C. In November 19098, Mr. Fanciulli joined Glenn H. Curtiss’ company. He was Vice President and General Manger of the Curtiss Exhibition Company. Among his many varied duties Mr. Fanciulli established schools of aviation and directed the demonstration and sale of Curtiss aeroplanes in the United States and Europe. He promoted or conducted some of the largest air meets in the United States prior to 1913. He collaborated with the United States Army and the United States Navy in developing aeroplane specifications. Mr. Fanciulli wrote magazine articles, employed and directed aviators obtaining contracts for them. Mr. Fanciulli sold the United States Navy its first biplane and the United States Army its second biplane. He also sold czarist Russia its first plane for their Navy. Mr. Fanciulli left the Glenn H. -

FAA Aviation News- September/October 2009

FAASAFETY FIRST FORAviation GENERAL AVIATION NewsSeptember/October 2009 Unlimited Excitement A Vintage Lot Up Close and Personal Bigger, Faster, Heavier In this issue, we focus on exhibition flying safety. Highlighted are the FAA’s role at the National Championship Air Races & Air Show, the challenges of competition and formation flying, and the behind-the-scenes efforts to keep vintage aircraft and their legacy thriving and flying. The airplane is a Hawker Sea Fury. Photo by James Williams. U.S. Department of Transportation Features Federal Aviation Administration UNLIMITED EXCITEMENT ISSN: 1057-9648 Biggest little city meets the biggest air race ...................................5 FAA Aviation News BY LYNN MCCLOUD September/October 2009 Volume 48/Number 5 A VINTAGE LOT Raymond H. LaHood Secretary of Transportation What it takes to keep vintage aircraft flying safely .........................8 J. Randolph Babbitt Administrator BY TOM HOFFMANN Margaret Gilligan Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety John M. Allen Director, Flight Standards Service Anne Graham Acting Manager, General Aviation and Commercial Division UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL Susan Parson Editor Lessons learned from formation flight training ..........................11 Lynn McCloud Managing Editor BY SUSAN PARSON Louise Oertly Associate Editor Tom Hoffmann Associate Editor James R. Williams Assistant Editor / Photo Editor BIGGER, FASTER, HEAVIER John Mitrione Art Director How one man helps keep aviation history alive ..........................14 Published six times a year, FAA Aviation News promotes aviation safety by BY JAMES WILLIAMS discussing current technical, regulatory, and procedural aspects affecting the safe operation and maintenance of aircraft. Although based on current FAA policy and rule interpretations, all material is advisory or informational LIGHTER THAN AIR in nature and should not be construed to have regulatory effect. -

Proceedings 2008.Pmd

VOLUME 12 Publisher ISASI (Frank Del Gandio, President) Editorial Advisor Air Safety Through Investigation Richard B. Stone Editorial Staff Susan Fager Esperison Martinez Design William A. Ford Proceedings of the ISASI Proceedings (ISSN 1562-8914) is published annually by the International Society of Air Safety Investigators. Opin- 39th Annual ISASI 2008 PROCEEDINGS ions expressed by authors are not neces- sarily endorsed or represent official ISASI position or policy. International Seminar Editorial Offices: 107 E. Holly Ave., Suite 11, Sterling, VA 20164-5405 USA. Tele- phone: (703) 430-9668. Fax: (703) 450- 1745. E-mail address: [email protected]. Internet website: http://www.isasi.org. ‘Investigation: The Art and the Notice: The Proceedings of the ISASI 39th annual international seminar held in Science’ Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, features presentations on safety issues of interest to the aviation community. The papers are presented herein in the original editorial Sept. 8–11, 2008 content supplied by the authors. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada Copyright © 2009—International Soci- ety of Air Safety Investigators, all rights reserved. Publication in any form is pro- hibited without permission. Permission to reprint is available upon application to the editorial offices. Publisher’s Editorial Profile: ISASI Pro- ceedings is printed in the United States and published for professional air safety inves- tigators who are members of the Interna- tional Society of Air Safety Investigators. Content emphasizes accident investigation findings, investigative techniques and ex- periences, and industry accident-preven- tion developments in concert with the seminar theme “Investigation: The Art and the Science.” Subscriptions: Active members in good standing and corporate members may ac- quire, on a no-fee basis, a copy of these Proceedings by downloading the material from the appropriate section of the ISASI website at www.isasi.org. -

Mabel Bell “What a Man My Husband Is … Flying Machines to Which Telephones and Torpedoes Are to Be Attached Occupy the First Place Just Now.”1 Mabel Bell 23

Mabel Bell “What a man my husband is … Flying machines to which telephones and torpedoes are to be attached occupy the first place just now.”1 Mabel Bell 23 1857-1923 Miss Mabel Hubbard knew she was Gardiner Hubbard was a patent lawyer accepting a challenge when she agreed to and financier with a keen interest in the marry the brilliant and quirky inventor, telegraph business. Coincidentally, Alec was Alexander Graham Bell. He became her life’s experimenting in his spare time with ways to work—and what a body of work it was. improve telegraph transmission, an offshoot of his fascination with sound and hearing. The romance and lifelong partnership began Gardiner Hubbard offered to co-finance Alec’s in Massachusetts in 1873. He was a Scottish experiments in exchange for a business interest emigrant, teaching elocution to deaf students in any new patents. It made perfect sense: in Boston. She was one of his pupils. Mabel If Alec were to woo Mabel, he would need had lost her hearing at the age of five because more than a teacher’s salary and an interesting of scarlet fever. Isolated by silence, she would hobby. He agreed to the partnership, but have eventually lost her speech as well, if not struggled to balance his priorities. Alec’s for her determined parents. Gardiner and first love was his work with the deaf, and the Gertrude Hubbard were wealthy and willing telegraph experiments threatened to interfere to go to great lengths to keep their daughter with that. He might well have abandoned the integrated in the hearing world. -

Aviation Pioneers - Who Are They? Alexander Graham Bell

50SKYSHADESImage not found or type unknown- aviation news AVIATION PIONEERS - WHO ARE THEY? ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL News / Personalities Image not found or type unknown Telephone, photophone, metal detector, hydrofoils, aeronautics..... © 2015-2021 50SKYSHADES.COM — Reproduction, copying, or redistribution for commercial purposes is prohibited. 1 Alexander Graham Bell (March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922)was a Scottish-born scientist, inventor, engineer and innovator who is credited with inventing the first practical telephone. Bell's father, grandfather, and brother had all been associated with work on elocution and speech, and both his mother and wife were deaf, profoundly influencing Bell's life's work His research on hearing and speech further led him to experiment with hearing devices which eventually culminated in Bell being awarded the first US patent for the telephone in 1876 Bell considered his most famous invention an intrusion on his real work as a scientist and refused to have a telephone in his study. First invention As a child, young Bell displayed a natural curiosity about his world, resulting in gathering botanical specimens as well as experimenting even at an early age. His best friend was Ben Herdman, a neighbor whose family operated a flour mill, the scene of many forays. Young Bell asked what needed to be done at the mill. He was told wheat had to be dehusked through a laborious process and at the age of 12, Bell built a homemade device that combined rotating paddles with sets of nail brushes, creating a simple dehusking machine that was put into operation and used steadily for a number of years.In return, John Herdman gave both boys the run of a small workshop in which to "invent". -

Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge

Mount Clemens Public Library Local History Sketches Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge (©2008 by Mount Clemens Public Library. All rights reserved.) s far as anyone knows, Thomas Etholen Selfridge never visited Mount Clemens, Michigan, but Ahis name is forever entwined with the history of the community. Thomas E. Selfridge was born in San Francisco on February 2, 1882. Little is known about his early life. He was graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point with the Class of 1903. Selfridge ranked 31st in the class of 96 cadets that year; future general Douglas MacArthur was first. After graduation Selfridge was commissioned a lieutenant in the Field Artillery, but his interest clearly lay in the emerging field of aeronautics. In 1907, he met Dr. Alexander Graham Bell, who was experimenting with powered flight. Bell was impressed with the eager young lieutenant and asked President Theodore Roosevelt to have Selfridge assigned as an official military observer of a flight demonstration he had planned. As a result of his association with Bell, Lt. Selfridge became a member of the Aerial Experiment Association (A.E.A.), along with Glenn H. Curtiss, and two Canadian engineers named F.W. Baldwin and J.A.D. McCurdy. Selfridge designed the group's first airplane, designated Aerodrome Number One, but nicknamed "Red Wing" because of the red silk covering its wings. Selfridge did not have the opportunity to pilot the "Red Wing" himself; the trials were conducted by F.W. Baldwin. Selfridge's first flight came on May 17, 1908, when he piloted Aerodrome Number Two, nicknamed "White Wing," for a distance of 93 yards at a height of ten feet! On September 17, 1908, Orville Wright was preparing to demonstrate his flying machine to Army officials at Fort Myer, Virginia, when a fellow officer urged Lt. -

The Wright Patent Lawsuit: Reflections on the Impact on American Aviation

Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research Volume 20 Number 3 JAAER Spring 2011 Article 4 Spring 2011 The Wright Patent Lawsuit: Reflections on the Impact on American Aviation Benjamin J. Goodheart Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University - WW, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer Scholarly Commons Citation Goodheart, B. J. (2011). The Wright Patent Lawsuit: Reflections on the Impact on American viation.A Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 20(3). Retrieved from https://commons.erau.edu/ jaaer/vol20/iss3/4 This Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Goodheart: The Wright Patent Lawsuit: Reflections on the Impact on American Wright Patent FORUM THE WRIGHT PATENT LAWSUIT: REFLECTIONS ON THE IMPACT ON AMERICAN AVIATION Benjamin J. Goodheart The Wright brothers, it must be conceded, were the first to fly a powered, heavier-than-air machine in sustained flight and under control. To deny them this rightful distinction is to willfully ignore fact (Hayward, 1912). Their contributions to aviation are innumerable, and without their insight, man may have been years awaiting what they accomplished in 1903. The Wrights' status as first in flight notwithstanding, their treatment of the issues surrounding the patent which was taken on their aircraft was harmful to the progress of aviation in the years following their success at Kitty Hawk. To claim that they owed the world the whole of their invention, and by extension, the profits arising from it, is unreasonable; but to suppose that in pursuit of their rightful gains, they would not impede any other from pursuing experimentation and improvement of aircraft is an expectation that is difficult to argue. -

Minutes by J. A. D. Mccurdy, from September 21, 1908, to September 26, 1908

Minutes by J. A. D. McCurdy, from September 21, 1908, to September 26, 1908 A meeting was held on Sept. 20, 21 st 1908, by order of the Chairman, at 1331 Conn. Ave., Washington, D. C. at 10 A. M. Present, A. G. Bell, G. H. Curtiss, F. W. Baldwin and J. A. D. McCurdy. Owing to the death of Lieut. Thomas E. Selfridge, J. A. D. McCurdy was elected Secretary as his successor. Special business before the meeting was the framing of th? two resolution in reference to the unfortunate accident at Fort Myer, which caused the death of our late Secretary. The following resolution was decided upon to convey to the parents of Lieut. Selfridge our sympathy in their great loss:— RESOLVED, that the Aerial Experiment Association place on record our high appreciation of our late Secretary. Lieut. Thomas E. Selfridge, who met death in his efforts to advance the art of aviation. The Association laments the loss of a dear friend and valued associate; the United States Army loses a valuable and prominent army officer, and the world an ardent student of aviation who made himself familiar with the whole progress of the art in the interests of his native country. RESOLVED, that a committee be appointed by the Chairman to prepare a biography of our friend, the late Thomas M. Selfridge, for incorporation into the records of the Association. RESOLVED, that a copy of these resolutions be transmitted to the parents of Lieut. Thomas Selfridge. Resolution No. 2, which follows, conveys to Mr. Orville Wright the idea that the members of the Association sympathise with him in his grief over the death of Lieut. -

Bulletins, from October 5, 1908 to December 28, 1908

Bulletins, from October 5, 1908 to December 28, 1908 ASSOCIATION'S COPY BULLETINS OF THE Aerial Experiment Association 3 Bulletin No. XIII Issued Monday, Oct. 5, 1908 THE ASSOCIATION'S COPY. BEINN BHREAGH, NEAR BADDECK, NOVA SCOTIA Bulletins of the Aerial Experiment Association . BULLETIN NO.XIII ISSUED MONDAY OCT. 5, 1908 . Beinn Bhreagh, Near Baddeck, Nova Scotia . TABLE OF CONTENTS. 1. Editorial Notes and Comments:— Historical Notes 1–3 Meeting of Association, Sept. 21, 1908 4–5 Meeting of Association, Sept. 26, 1908 5–7 2. Hammondsport Work:— Preparation for patents on Hammondsport Work 8–17 Letter from Mauro, V Cameron, Lewis & Massie, Sept. 24 8–8 Reply by Dr. Bell, Sept. 29 8–16 Note from Mr. Edmund Lyon, Sept. 29 17–17 Bulletins, from October 5, 1908 to December 28, 1908 http://www.loc.gov/resource/magbell.14100102 3. Beinn Bhreagh W ro ork:— Work of Beinn Bhreagh Laboratory by William F. Bedwin Supt 18–26 4. Miscellaneous Communications:— On the Death of Selfridge, by Mrs. Bell 27–28 On giving information to the U S Army 29–32 Bell to Curtiss, Sept. 29 29–31 Curtiss to Bell, Oct. 1 31–31 Bell to President Roosevelt Oct. 5 32–32 What the work of the Aerial Experiment Association means by Carl Dienstbach 33–36 Illustrations . Present condition of aerodrome No 5 21 New propellers for the Dhonnas Beag 22 The new propellers with reversing gear 23 The new propellers on the Dhonnas Beag 24 Present condition of Oionos structure 25 McLean's adjustable propeller 26 1 Editorial Notes and Comments . -

Fall 2019 Ben T

InsideDaedalus this issue: Dark Night in Route Pack VI Page 8 Fall 2019 Ben T. Epps Sets the Bar High Page 18 Breaking Barriers Page 22 Flyer D-Day Doll Revisits Normandy Page 57 First to fly in time of war The premier fraternity of military aviators Contents Fall 2019, Vol. LX No. 3 Departments 5 Reunions 6 Commander 7 Executive Director 11 New Daedalians 14 Book Reviews 24 In Memoriam 26 Awards 33 Flightline 54 Eagle Wing 53 Flight Contacts Features 12 Hereditary Membership 18 Ben T. Epps Sets the Bar High 56 Plant the Seed, Watch it Grow 57 D-Day Doll Revisits Normandy Articles 8 Dark Night in Route Pack VI 16 Flying with Little SAM 21 David vs. Goliath 22 Breaking Barriers The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement. THE ORDER OF DAEDALIANS was organized on March 26, 1934, by a representative group of American World War I pilots to perpetuate the spirit of patriotism, the love of country, and the high ideals of sacrifice which place service to nation above personal safety or position. The Order is dedicated to: insuring that America will always be preeminent in air and space—the encouragement of flight safety—fostering an esprit de corps in the military air forces—promoting the adoption of military service as a career—and aiding deserving young individuals in specialized higher education through the establishment of scholarships. THE DAEDALIAN FOUNDATION was incorporated in 1959 as a nonprofit organization to carry on activities in furtherance of the ideals and purposes of the Order.