New Construction Methods and New Roles for Engineers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanical Design Engineer

Mechanical Design Engineer Department: Engineering Reports to: Engineering Manager Location: Union City, CA; Port Orchard, WA or El Paso, TX Experience: 4 to 6 years, preferably in Mechanical Engineering Job Type: Full Time (exempt) Education: B.S. degree in engineering Travel: Up to 10% About Us Tournesol Siteworks is a national manufacturer of landscape products for green buildings based in the San Francisco Bay Area. We’re a growing company, with manufacturing facilities in California, Washington and Texas, working on environmentally-conscious commercial construction projects across the U.S and Canada. We’re a tight-knit group looking for a real team player. About the Team The Engineering Team is currently seeking a Mechanical Design Engineer to work at one of our manufacturing locations. The Engineering team is composed of members with varied but complimentary experience, qualifications, and skills and is responsible for the design, engineering, analysis, and documentation of products, systems, structures, materials, and projects, small and simple to large and complex that fulfill objectives and requirements. About the Role As a Mechanical Design Engineer, you’ll work under the direction of the Engineering Manager on custom projects and standard products reviewing criteria, identifying and analyzing solutions, applying and transferring information, choosing best solutions, and making decisions that directly impact and contribute to final designs. You’ll be based in one of our manufacturing locations (Union City, CA; El Paso, TX; Port Orchard, WA) and you’ll be required to travel occasionally to our other facilities. You’ll have a direct hand in accomplishing our #1 goal – a successful project in every way. -

Virtual and Mixed Prototyping Techniques and Technologies for Consumer Product Design Within a Blended Learning Design Environment

INTERNATIONAL DESIGN CONFERENCE - DESIGN 2018 https://doi.org/10.21278/idc.2018.0428 VIRTUAL AND MIXED PROTOTYPING TECHNIQUES AND TECHNOLOGIES FOR CONSUMER PRODUCT DESIGN WITHIN A BLENDED LEARNING DESIGN ENVIRONMENT M. Bordegoni, F. Ferrise, R. Wendrich and S. Barone Abstract Both physical and virtual prototyping are core elements of the design and engineering process. In this paper, we present an industrial case-study in conjunction with a collaborative agile design engineering process and “methodology.” Four groups of heterogeneous Post-doc and Ph.D. students from various domains were assembled and instructed to fulfill a multi-disciplinary design task based on a real-world industry use-case. We present findings, evaluation, and results of this study. Keywords: virtual prototyping, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), engineering design, collaborative design 1. Introduction Virtual and mixed prototyping within a collaborative blended learning environment is considered an enabling design support technique that allows designers to gain first-hand appreciation of existing or near-future conditions through active engagement with a wide variety in prototyping techniques and prototypes. The product design process (PDP) follows a dual approach and method based on a combination of a blended learning environment (Boelens et al., 2017) and interactive affective experience prototyping (Buchenau and Suri, 2000). The virtual prototyping summer school (VRPT-SS) facilitates this combinatorial collaborative setting to immerse learners in the externalization and representation of their ideas quickly, exploring and communicating their ideas with others. During the course of the week a series of evaluations on the prototyping progressions are made. The spectrum of virtual and mixed prototyping is quite extensive and has multiple definitions and meanings according to literature (see Wang, 2002, and Zorriassatine et al., 2003). -

Practical Impacts of Design-Build on the Design Engineer

Practical Impacts of Design-Build on the Design Engineer Presented by: Joseph C. Staak, Esq. Smith, Currie & Hancock LLP 2700 Marquis One Tower 245 Peachtree Center Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30303-1227 Tel: 404.582.8026 [email protected] www.smithcurrie.com November 2012 NOTES Practical Impacts of Design-Build on the Design Engineer I. INTRODUCTION Project delivery using Design-build has become increasingly popular over the last thirty years. Owners have recognized the advantages of using a single source of responsibility for a project’s design and construction. Many contractors have recognized the popularity of design-build and have made adjustments to their business model allowing them to offer this one-stop system for project delivery. Architects and engineers also recognize that, unless they want to avoid this ever growing segment of the project design market, they too must adapt to working directly with the contractor. Nearly half of all commercial construction in the United States is being awarded using design-build as the project delivery vehicle, and the reasons are obvious. Owners perceive multiple advantages in using design-build. These advantages include, but are not limited to, a single source of responsibility for design and construction, the increased risk design-build transfers to the design- builder, the opportunity to fast track design and construction to reduce the time from concept to completion, and the owner’s ability to take advantage of the design-builder’s expertise in identifying design solutions. Changes in public procurement during the last 20 years have precipitated an explosion in the use of design-build by government agencies. -

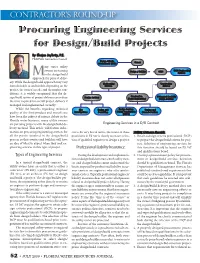

Procuring Engineering Services for Design/Build Projects by Shajan Joykutty, P.E

Contractor’s Round-up Procuring Engineering Services for Design/Build Projects By Shajan Joykutty, P.E. FSAWWA Contractors Council DDesignesign CCriteriariteria OOwnerwner PProfessionalrofessional ((DCP)DCP) any water utility OO&M&M EEngineeringngineering owners are turning DDesignesign / BBuilderuilder OO&M&M SServiceservices to the design/build Services Mapproach for project deliv - ery. While the design/build approach may vary EEngineeringngineering CConstructiononstruction from desirable to undesirable, depending on the SServiceservices SServiceservices project, the owner’s needs, and the market con - ditions, it is widely recognized that the de - CConstructiononstruction DDelegatedelegated SSpecialtypecialty DDesignesign SServiceservices Delegated Specialty sign/build system of project delivery can reduce PPhasehase EEngineeringngineering DDesignesign SServiceservices the time required for overall project delivery if managed and implemented correctly. While the benefits regarding technical SSiteiite DDesignesiign aandnd DDesignesign SServiceservices TTestingestiing aandnd IInvestigationsnvestiigatiions PPermittingermiittiing DDuringuring CConstructiononstruction FForensicorensiic SServiceserviices quality of the final product and overall cost ((DSDC)DSDC) have been the subject of intense debate in the Florida water business, many utility owners are pursuing projects with the design/build de - Engineering Services in a D/B Contract livery method. This article will feature infor - mation on procuring engineering services for tracts. In very broad terms, the intent of these Utility Owners Should: all the parties involved in the design/build provisions in FS 287 is clearly to ensure selec - 1. Retain a design criteria professional (DCP) process so that owners and builders will have tion of qualified engineers to design a project. to prepare the design/build criteria for proj - an idea of what to expect when they seek en - ects. Selection of engineering services for gineering services in this type of project. -

Mechanical Design Engineer

MECHANICAL DESIGN ENGINEER PURPOSE OF POSITION ESSE NTIAL DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Design of custom, diamond finishing systems, assemblies, fixtures, and tooling Use 3D modeling software (Solidworks) to used worldwide for a variety of perform accurate design and detail work to manufacturing processes and finished ensure proper mechanical design based on goods. Support design work in all project requirements and adhering to product groups as required by sales customer specifications. trends and volume. Create assembly and part files using best- practice techniques with a concentrated effort on DFM principles within the scope of the CONTACTS company’s manufacturing capacity. Reports to the Machine Build Manager Continuously review products and suggest and has no supervisory responsibility. cost reductions for new and existing designs. Has inside contacts with engineering staff, manufacturing personnel and order Update designs, assemblies, files, and prints as processing department. Has outside required to reflect changes, modifications, and contacts with customers, distributors, revisions. and vendors. Complete final file of drawings, BOMs, technical notes, build instructions, and manual updates as necessary to describe both ESSENTIAL QUALIFICATIONS standard and custom assemblies and machines. Update MRP data to match new and revised The requirements listed below are engineering designs and prints. representative of the knowledge, skill, Respond to customer support inquiries at all and/or ability required. Reasonable stages of product design and life cycle. accommodations may be made to Assist sales team and marketing with layout enable individuals with disabilities to proposals, quotations, and marketing perform the essential functions. literature. Maintains a high level of professionalism in communicating with customers, performing demonstrations, providing technical support, [email protected] and resolving problems. -

Design Engineer

Mac Aero Interiors Ltd Trading as MAC Interiors Job Description Job Title: Chief Design Engineer Job Holder: Responsible to: Head of Design Applicable CS25 2x.561, 2x.562, 2x.581, 2x.601, 2x.603, 2x.605, 2x.607, 2x.609, 2x.611, 2x.613, 2x.619, 2x.621, 2x.623 , 2x.625, 2x.629, 2x.631, 2x.785, 2x.787, subjects (and the 2x.789, 2x.791, 2x.793, 2x.795, 2x.803, 2x.807, 2x.809, 2x.810, 2x.811, equivalent 2x.812, 2x.813, 2x.815, 2x.817, 2x.819, 2x.820, 2x.831, 2x.851, 2x.853, subjects within 2x.854, 2x.855, 2x.856, 2x.857, 2x.858, 2x.869, 2x.899, 2x.1301, 2x.1309, CS23, CS27 & CS29) 2x.1310, 2x.1316, 2x.1353, 2x.1411, 2x.1415, 2x.1419, 2x.1421, 2x.1423, 2x.1439, 2x.1441, 2x.1443, 2x.1445, 2x.1447, 2x.1449, 2x.1450, 2x.1453, 2x.1455, 2x.1519, 2x.1529, 2x.1541, 2x.1543, 2x.1557, 2x.1561, 2x.1581, 2x.1583, 2x.1585, 2x.1701, 2x.1703, 2x.1705, 2x.1707, 2x.1709, 2x.1711, 2x.1713, 2x.1715, 2x.1717, 2x.1719, 2x.1721, 2x.1729 Appendix F, Appendix H , Appendix K, Appendix L Description/ To ensure that the Design staff have the relevant experience, training and qualifications for such tasks. Responsibilities: To ensure that the design staff is of sufficient number and have the appropriate authority to be able to discharge their allocated responsibilities. To ensure that the accommodation, facilities and equipment are adequate to enable the staff to achieve objectives. -

Architectural and Engineering Basic Services Fee Negotiation Guidelines

Architectural and Engineering Basic Services Fee Estimating Guidelines Basic Services is the design work customary on a typical project to take an established building program, site, and budget, and then develop the architectural design, engineer the building systems, produce construction documents, and perform construction administration for a single phase project. Basic Services include the design services customary on every project such as architectural, structural, civil, mechanical, and electrical engineering services. Basic Services are described in the Standard Consulting Agreement. The following method estimates the Basic Services fees using the Amount Available for Construction (AAC) from the established project budget. The fees are expressed as percentage of AAC for six (6) projects types with differing levels of complexity for both New Construction and Renovation. The Project Types are: Project Type I – Considerably Less than Average Complexity: Farm Structures, shop & Maintenance, Service, Warehouses, Storage Facilities, Parking Structures. Project Type II – Less Than Average Complexity: Student Housing, Office Buildings, Complex Parking Structures. Project Type III – Average Complexity: Classroom Facilities, General Teaching Spaces, Medical Offices, Clinics, Gymnasia. Project Type IV – More Than Average Complexity: Complex University Buildings, Engineering Laboratories, University Libraries, Dining Facilities, Theaters, Arenas, Auditoriums, Medical Schools. Project Type V – Considerably More than Average Complexity: Science and Medical Research Buildings, Hospitals, Museums. Project Type VI – Engineering Projects: Campus/Building Chilled Water, Steam, Fire Protection, or Hot Water Systems; Campus/Building Electrical Distribution Systems; Building Replacement Mechanical or Electrical Systems; Building or Campus Generator Systems; Campus Fire Alarm or Security Systems; Outdoor Lighting or Sports Lighting; Retrofit Building Fire Protection Systems; Campus Voice/Data Systems. -

Design-Build by Zane Satterfield, P

PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES CENTER Design-Build By Zane Satterfield, P. E., NESC Engineering Scientist Summary Design-build is a method of construction where the design and construction tasks are contracted with a single entity known as the design-builder or design-build contractor. The design-build meth- od is gaining popularity, with some projections indicating that more than half of all non-residential construction projects in the U.S. will be design-build by 2015. This Tech Brief discusses some of the aspects of the design-build method and how it might be used for water and wastewater projects. What is Design-Build? Design-build is a construction project delivery system where the design and construction as- pects are contracted with a single entity known as the design-builder or design-build contrac- tor. Design-build is more streamlined than the traditional method, often referred to as design- http://nats320.blogspot.com/ bid-build, where design and construction were clearly separated. The design-builder is usually the general con- Image courtesy of tractor, but can also be the architect or engi- neer. By incorporating the designer and con- tractor, design-build minimizes the project risk for an owner and reduces the delivery schedule by overlapping the design phase and construc- tion phase of a project. Rather than first bid- ding or engaging an architectural or engineering firm to design the project and then bidding out a contractor to build the project (i.e., the design- bid-build method), the design-build contractor packages the engineering design services in with The Washington National’s ballpark in the nation’s capital is one of the the construction. -

Mechanical Design Engineer Type: Full Time (Mon-Fri 7:00Am- 5:00Pm)

Job Title: Mechanical Design Engineer Type: Full Time (Mon-Fri 7:00am- 5:00pm) Job Description: Martin Enclosures is seeking an Mechanical Design Engineer to design and develop OEM and Data Center Solutions from server racks and cabinets, to power solutions and accessories. Martin prides itself on it's custom mechanical engineering to develop the industry's highest quality Cabinet and Enclosure Solutions. Core job responsibilities will be working one on one with the customer to design/ develop desired solutions in order to accomplish their end goal. Work as a member of the Engineering team to assist the department in producing a smooth, efficient flow of quality work through the company. Will receive direction and work assignments from other members of the Engineering department, in coordination with the immediate supervisor. Job Responsibilities: • Design and develop new server rack, cabinet, and enclosure applications. • Design and develop new power solutions. • New product development. • Consult with customers and quote customer’s custom enclosure applications. • Be able to learn our product line in order to help and quote customers. • Attend trade shows • Provide initial design concepts, including research of new components. • Provide initial time and material estimates for quotes • Compiling costs and lead times for non-recurring engineering charges • Create mechanical design prints • Provide guidance on design specifics (fastener torques, selection of fasteners, acceptable tolerances, etc.) • Create and maintain bills of materials for fabricated and assembled products. • Construct prototypes. • Perform mechanical and/or basic electrical testing to verify designs meet customer requirements. • 1st piece inspection and approval of prototype parts or purchased parts, including review or completion of any required test and inspection reports. -

Frequently Asked Questions

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS CITY OF FERNLEY 595 SILVER LACE BLVD. FERNLEY, NV 89408 775-784 -9810 Revised 5/2/2019 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ARCHITECTS Architect, as used in these questions and answers, is a Nevada registered architect, per NRS 623, unless noted otherwise. A-1. Does a set of plans stamped and signed by an architect registered in a state other than Nevada meet the requirements for submittal in Nevada? No. Only design professionals currently registered or licensed in Nevada may submit plans to a Building Department. A-2. May an architect overstamp documents prepared and stamped by an out-of-state architect for submittal in Nevada? No. A Nevada architect may only stamp design documents prepared by him or under his responsible control. A-3. May an owner, contractor or building official make changes to plans prepared by an architect? No. Changes or modifications to technical documents prepared by a registered professional may only be made by that professional, or a professional meeting the criteria set forth in question A-4. A-4. May a Nevada architect make changes to plans prepared by another Nevada registered or licensed professional? Yes, with conditions. A Nevada architect may revise or change plans prepared by another Nevada registrant or licensee under the following conditions: a. Every reasonable effort must be taken to notify and obtain concurrence from the original design professional with respect to changes to the original plans. b. The work must be within the scope of his practice. c. The architect initiating changes to the plans assumes full responsibility for those changes and their effects upon the remainder of the project. -

What Is Design Engineering and How Should It Be Taught? – Proposing a Didactical Approach

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING DESIGN ICED 05 MELBOURNE, AUGUST 15-18, 2005 WHAT IS DESIGN ENGINEERING AND HOW SHOULD IT BE TAUGHT? – PROPOSING A DIDACTICAL APPROACH Martin Grimheden and Mats Hanson Keywords: design education, definition of design, didactical approach 1 Introduction Design engineering is being taught at the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) in the form of a Master of Science program, Design and Product Realization. The program started in August 2003, and has been rated so far by the students as the third most popular engineering program. Each year approximately 100 students are accepted. When the program was introduced by KTH, the subject of design engineering was chosen in favour of engineering design, with the purpose of establishing the program independently in relation to existing programs in mechanical engineering, vehicle engineering etc, and to establish the new program into the area of ‘development of attractive products’. The aim of this paper is to present results from a didactical analysis performed on the subject of design engineering. 1.1 Objectives Didactics is a field of educational studies mostly referring to research aimed at investigating what’s unique with a particular subject, and how the particular subject ought to be taught. The purpose of the didactical analysis is to identify and describe the identity and legitimacy of the subject (what is design engineering, and why should design engineering be taught?) as well as its implications on the educational methods (which material should be taught, and how?). The paper is structured as follows: In section two we describe the context of this study, providing a background and perspectives from research on education, the interpretation of the concept of design in Sweden and conclude with some examples of the industrial context of design engineering. -

What Is Wrong with Reliability Engineering?

What is wrong with Reliability Engineering? R.W.A. Barnard Lambda Consulting PO Box 11826, Hatfield 0028, South Africa Mobile : +27 82 344 0345 [email protected] Copyright © 2008 by R.W.A. Barnard. Published and used by INCOSE with permission. Abstract . Notwithstanding the implementation of reliability engineering programs by companies, it is not uncommon to observe many instances of low field reliability. This paper briefly describes the essence of reliability engineering, which has prevention of failure as primary objective. Possible reasons for the apparent failure of reliability engineering, especially as practised by the defence industry, are given. It argues that incorrect practices are often applied, frequently performed by incorrect people in the organisation, and at the incorrect time during the product or system life cycle. The value of reliability engineering as specialty area of systems engineering can be improved by learning from best practices used by industry leaders. The essence of reliability engineering —I believe that the concept of failure is central to understanding engineering, for engineering design has as its first and foremost objective the obviation of failure.“ Henry Petroski High field reliability is a highly desirable attribute of any product, system or plant. For defence products and systems, reliability may be the differentiating factor determining mission success or loss of life. For industrial systems and plants, reliability directly influences inherent availability and therefore return on investment. For commercial products, high reliability may provide a supplier with a competitive advantage, resulting in increased market share and therefore higher profits. In all cases, reliability of a product or system is strongly influenced by decisions made during the design and development process.