The Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in Massachusetts Statement on U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fisher College Course Catalog

FISHER COLLEGE COURSE CATALOG Academic Year 2019-2020 Fisher College Course Catalog 2019-2020 Table of Contents General Information...........................................................2 College Policies.................................................................5 Academic Information.......................................................14 Admissions, Financial Information, and Aid..........................42 Student Services..............................................................55 Student Life.....................................................................60 Program Requirements......................................................64 Minors...........................................................................134 Course Descriptions........................................................137 Directory.......................................................................238 Appendix A: Academic Calendars....................................246 Appendix B: Schedule of Charges....................................250 Fisher College 118 Beacon St Boston, MA 02116 617-236-8800 1 General Information General Information Mission Fisher College improves lives by providing students with the knowledge and skills necessary for a lifetime of intellectual and professional pursuits. Motto Ubique Fidelis: “Everywhere Faithful” Purposes • Fisher College enables students to earn a degree and seek a job upon graduation. • Fisher College provides access to an education to students seek- ing the tools they need to achieve their goals. -

Student Housing Trends 2017-2018 Academic Year

Student Housing Trends 2017-2018 Academic Year Boston’s world-renowned colleges and universities provide our City and region with unparalleled cultural resources, a thriving economic engine, and a talented workforce at the forefront of global innovation. However, the more than 147,000 students enrolled in Boston-based undergraduate and graduate degree programs place enormous strain on the city’s residential housing market, contributing to higher rents and housing costs for Boston’s workforce. In Housing a Changing City: Boston 2030, the Walsh Administration outlined three clear strategic goals regarding student housing: 1. Create 18,500 new student dormitory beds by the end of 2030;1 2. Reduce the number of undergraduates living off-campus in Boston by 50%;2 3. Ensure all students reside in safe and suitable housing. The annual student housing report provides the opportunity to review the trends in housing Boston’s students and the effect these students are having on Boston’s local housing market. This report is based on data from the University Accountability Reports (UAR) submitted by Boston-based institutions of higher education.3 In this edition of Student Housing Trends,4 data improvements have led to more precise enrollment and off-campus data, allowing the City to better distinguish between students that are or are not having an impact on the private housing market. The key findings are: ● • Overall enrollment at Boston-based colleges and universities is 147,689. This represents net growth of just under 4,000 (2.8%) students since 2013, and a 2,300+ (1.6%) student increase over last year. -

Suffolk University Institutional Master Plan Notification Form

SUFFOLK UNIVERSITY Institutional Master Plan Notification Form Submitted to Prepared by Boston Redevelopment Authority Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts In association with Submitted by Chan Krieger Sieniewicz Suffolk University CBT/Childs Bertman Tseckares, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts Rubin & Rudman LLP Suffolk Construction January, 2008 SUFFOLK UNIVERSITY Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION Background.............................................................................................................................1-1 The Urban Campus ................................................................................................................1-2 Institutional Master Planning Summary ..................................................................................1-3 2002 Suffolk University Institutional Master Plan....................................................1-3 2005 Amendment to Suffolk University Institutional Master Plan ...........................1-4 2007 Renewal of the Suffolk University Institutional Master Plan...........................1-5 2007 Amendment to Suffolk University Institutional Master Plan – 10 West Street Student Residence Hall Project .....................................................1-5 Public Process and Coordination............................................................................................1-6 Institutional Master Plan Team .............................................................................................1-10 2. MISSION AND OBJECTIVES Introduction.............................................................................................................................2-1 -

FY 2005 Title III and Title V Eligible Institutions (PDF)

Title III and Title V Eligibility FY 2005 Eligible Institutions Group 1 STATE INSTITUTION CITY AK Sheldon Jackson College Sitka AK University of Alaska at Southeast Sitka Campus Sitka AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Bristol Bay Dillingham AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Chukchi Campus Kotzebue AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Kuskokwim Campus Bethel AK University of Alaska Fairbanks Northwest Campus Nome AL Alabama Southern Community College Monroeville AL Athens State University Athens AL Bevill State Community College Sumiton AL Enterprise-Ozark Community College Enterprise AL Faulkner State Community College Bay Minette AL Faulkner University Montgomery AL George C. Wallace Community College Dothan AL George C. Wallace State Community College Hanceville AL John C. Calhoun State Community College Decatur AL Lurleen B. Wallace Community College Andalusia AL Northeast Alabama Community College Rainsville AL Snead State Community College Boaz AL Southern Community College Tuskegee AL Troy State University Troy AL Troy State University Dothan Dothan AL Troy State University Montgomery Montgomery AL University of North Alabama Florence AR Arkansas Northeastern College Blytheville AR Arkansas State University Beebe Beebe AR Arkansas Technical University Russellville AR Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas De Queen AR Mid-South Community College West Memphis AR National Park Community College at Hot Springs Hot Springs AR North Arkansas College Harrison AR Phillips County Community College of the University of Arkansas -

Read the Report

The Boston Opportunity Agenda Ninth Annual Report Card May 2021 i A Historic Partnership Convening Partners and Investors Angell Foundation Archdiocese of Boston Catholic Schools Office Boston Charter Alliance Boston Children’s Hospital The Boston Foundation Boston Public Schools Bunker Hill Community College Catholic Charities Archdiocese of Boston City of Boston Combined Jewish Philanthropies of Boston EdVestors Nellie Mae Education Foundation New Profit Inc. Smith Family Foundation United Way of Massachusetts Bay and Merrimack Valley University of Massachusetts Boston ii Table of Contents Introduction | 2 A Strong Educational Foundation | 4 On Track for High School Graduation | 8 High School Graduation | 10 On Track for College, Career and Life | 14 Postsecondary Attainment | 16 Adult Learners | 20 Birth to Eight Collaborative | 22 Summer Learning Academies | 24 Generation Success | 26 Boston Opportunity Youth Collaborative | 28 Success Boston | 30 About Us | 32 Cover Photo: lakshmiprasad S | iStock Introduction Dear Friends, To describe the past year as incredibly difficult is an understatement. including MCAS, are not available this year. As students return to school Children, families and the educational institutions that serve them have and our systems work to close the learning gaps created by more than While devastating, dealt with once-in-a-century challenges to schooling as we know it. a year of disrupted learning, it is critical that all stakeholders understand the chaos of the In addition to the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd and others previous trends and baselines for each of our measures of success. It captured on video and highlighted in protests, and the increase in is equally critical that we report on measures that focus on where the year has also racial violence against those of Asian descent have laid bare the vast systemic shortfalls are as, together, we seek to create the necessary optimistically inequalities in our country rooted in White supremacy, race, ethnicity prerequisites for students to experience success. -

2018 Guide to Colleges & Universities

GUIDE TO NEW ENGLAND FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF BOSTON MAGAZINE IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE NEW ENGLAND BOARD OF HIGHER EDUCATION nebhe.org GUIDE TO NEW ENGLAND GUIDE TO NEW ENGLAND COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF BOSTON MAGAZINE TABLE OF CONTENTS: 4. 2018 GUIDE INTRODUCTION: COLLEGE IS WORTH IT 6. COLLEGES THAT WORK 10. FINANCIAL AID HELPS LOWER YOUR COSTS 1 4 . COLLEGE DECISION TIMELINE FOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS 16. TUITION BREAK: A REGIONAL PROGRAM WITH A BREAK ON OUT-OF-STATE TUITION 18. COLLEGE LISTINGS 30. INDEX 2018 Guide to New England Colleges and Universities is published by Boston magazine in partnership with the New England Board of Higher Education. All contents are copyright 2017 by Boston magazine. For information, contact Jaime Coval at [email protected] or 617.275.2007. BOSTONMAGAZINE.COM/EDUCATION | GUIDE TO COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES 2018 3 GUIDE TO NEW ENGLAND 2018 GUIDE INTRODUCTION: COLLEGE IS WORTH IT STUDENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES increasingly ask whether The New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE) works college is “worth it” and whether they can afford it. to foster innovation and collaboration in the region. Created in The answer comes in the form of counter questions: Can they 1955, NEBHE’s mission is to expand, through interstate coopera- afford not to pursue a college education? What will the impact be tion, the education opportunities and services available to the if they don’t get a college degree? Some students and families look region’s residents, with a focus on college affordability, access, to “return on investment,” and indeed, median annual earnings for and success. -

FISHER COLLEGE Course Catalog 2017-2018

FISHER COLLEGE Course Catalog 2017-2018 Table of Contents General Information.............................................................................3 College Policies...................................................................................7 Academic Information.........................................................................15 Admissions, Financial Information, and Aid ...........................................44 Student Services................................................................................58 Student Life.......................................................................................63 Program Requirements.......................................................................66 Minors.............................................................................................133 Course Descriptions..........................................................................136 Directory..........................................................................................235 Index..............................................................................................243 1 General Information General Information Mission Fisher College improves lives by providing students with the knowl- edge and skills necessary for a lifetime of intellectual and professional pursuits. Motto Ubique Fidelis: “Everywhere Faithful” Purposes • Fisher College enables students to earn a degree and seek a job upon graduation. • Fisher College provides access to an education to students seek- ing the tools -

Regional Locations of Cambridge College

Regional Locations of Cambridge College Cambridge College maintains regional locations in Massachusetts and Oversight and Communications across the United States offering undergraduate, graduate and post- The Provost/Vice President of Academic Affairs Office maintains over- graduate degrees and certificate programs. sight of the Cambridge College regional locations (sites). Regional site directors represent the College policies and procedures to students • Cambridge College Lawrence — Lawrence, MA and local agencies and act as the local authority in the chain of com- • Cambridge College Springfield — Springfield, MA munications. Administrative, academic and operations offices at the • Cambridge College Puerto Rico — Guaynabo, PR main campus engage with the regional Cambridge College offices • Cambridge College Southern California — Rancho Cucamonga, CA for purposes of strategic planning, information sharing, and problem solving. Regional site directors and faculty are the first choices when students have information needs or concerns. The main campus Cambridge College is accredited by the New England Commission of offices collaborate with the regional offices in supporting the needs of Higher Education (formerly the Commission on Institutions of Higher our students throughout the nation. Education of the New England Association of Schools and Colleges, Inc). Additionally, Cambridge College has sought and received state approval to operate in the states in which the regional locations are located. Boston All College programs are evaluated -

2017-2018 Course Catalogue

Course Catalogue 2017-2018 2017-18 Course Catalogue 2 | Urban College of Boston Urban College of Boston—At a Glance History and Founding of the College UCB was established to provide a link to higher education and economic opportunity for members of the urban community who have traditionally been underserved by higher education. The College had its beginnings almost 40 years ago as the Urban College Program, established by Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD), Inc. UCB was chartered in 1993 by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts as a co- educational, two-year degree-granting institution. In 2000, UCB became a fully independent college. Demographics Urban College student body represents the rich cultural and ethnic diversity of the city of Boston. Many of our students are non-traditional adult learners who face tremendous challenges in deciding to return to the classroom – language barriers, single-parent family responsibilities, lower-paying jobs and housing issues. The average age of UCB students is 39. 93% are women. 91% are minorities: Hispanic (62%); African American (18%); & Asian American (11%). More than 70% speak English as a second language. 2017-18 Course Catalogue 3 | Urban College of Boston Accreditation and Non-Profit Tax Tuition and Financial Aid Status Tuition is $296 per credit hour. The College is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and 70% of all students receive financial aid. Colleges (NEASC) and is a 501(c) 3 non- profit organization. Pell grants and scholarships are available. Enrollment, Programs of Study, and Resources Location of the College The College enrolls over 1,400 students Urban College of Boston is conveniently annually and offers three Associate of located in downtown Boston, close to Arts degrees in Early Childhood the Boston Common, the State House Education, Human Services and the city’s vibrant theatre district. -

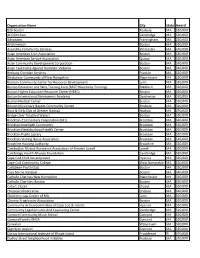

Organization Name

Organization Name City State Award 826 Boston Roxbury MA $10,000 ACCION East Cambridge MA $10,000 Advocates Framingham MA $10,000 ArtsEmerson Boston MA $10,000 Ascentria Community Services Worcester MA $10,000 Asian American Civic Association Boston MA $10,000 Asian American Service Association Quincy MA $10,000 Asian Community Development Corporation Boston MA $10,000 Asian Task Force Against Domestic Violence Boston MA $10,000 Bethany Christian Services Franklin MA $10,000 Bhutanese Community of New Hampshire Manchester NH $10,000 Bosnian Community Center for Resource Development Lynn MA $10,000 Boston Education and Skills Training Corp (BEST Hospitality Training) Medford MA $10,000 Boston Higher Education Resource Center (HERC) Boston MA $10,000 Boston International Newcomers Academy Dorchester MA $10,000 Boston Medical Center Boston MA $10,000 Boston Missionary Baptist Community Center Roxbury MA $10,000 Boys & Girls Club of Greater Nashua Nashua NH $10,000 Bridge Over Troubled Waters Boston MA $10,000 Brockton 21st Century Corporation (B21) Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Interfaith Community Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Neighborhood Health Center Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Public Library Brockton MA $10,000 Brockton Visiting Nurse Association Brockton MA $10,000 Brookline Housing Authority Brookline MA $10,000 Cambodian Mutual Assistance Association of Greater Lowell Lowell MA $10,000 Cambridge Health Alliance Foundation Cambridge MA $10,000 Cape Cod Child Development Hyannis MA $10,000 Cape Cod Community College West Barnstable MA -

Alfred University American International College (2) American

Trinity-Pawling School College Matriculations (3-year compilation) Alfred University Northern Arizona University American International College (2) Northwestern University (2) American University of Beirut Occidental College Arizona State University Old Dominion University Assumption College Oxford College of Emory University Auburn University Pace University, New York City (3) Babson College Pace University, Pleasantville Campus Berklee College of Music Pace University, White Plains Birmingham-Southern College Plymouth State University Boston College (2) Prairie View A&M University Boston University (3) Princeton University Bowdoin College Providence College Brandeis University Purdue University (3) Bucknell University (2) Queens University of Charlotte Campbell University Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (2) Carnegie Mellon University Rice University Case Western Reserve University Roanoke College (2) Castleton State College Rochester Institute of Technology Catawba College Roger Williams University (2) Clark University Sacred Heart University (5) Clarkson University Saint Anselm College (2) Clemson University Saint Francis University Coastal Carolina University Saint Joseph's University Colby College Saint Michael's College Colby-Sawyer College Salve Regina University College of Charleston (2) Seton Hall University College of William and Mary Sewanee: The University of the South Columbia University Siena College Concordia University - Montreal Skidmore College Cornell University Sophia University Curry College Southern Connecticut State -

Divinity School 2010–2011

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Divinity School 2010–2011 Divinity School Divinity 2010–2011 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 106 Number 3 June 20, 2010 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 106 Number 3 June 20, 2010 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a special disabled veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer or gender identity or expression. Editor: Lesley K. Baier University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans.