BRITISH BATTLESHIPS 1914–18 (2) the Super Dreadnoughts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

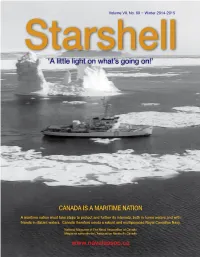

Volume VII, No. 69 ~ Winter 2014-2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… To date, the Royal Canadian Navy’s only purpose-built, ice-capable Arctic Patrol Vessel, HMCS Labrador, commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy July 8th, 1954, ‘poses’ in her frozen natural element, date unknown. She was a state-of-the- Starshell art diesel electric icebreaker similar in design to the US Coast Guard’s Wind-class ISSN-1191-1166 icebreakers, however, was modified to include a suite of scientific instruments so it could serve as an exploration vessel rather than a warship like the American Coast National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Guard vessels. She was the first ship to circumnavigate North America when, in Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada 1954, she transited the Northwest Passage and returned to Halifax through the Panama Canal. When DND decided to reduce spending by cancelling the Arctic patrols, Labrador was transferred to the Department of Transport becoming the www.navalassoc.ca CGSS Labrador until being paid off and sold for scrap in 1987. Royal Canadian Navy photo/University of Calgary PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele In this edition… PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] NAC Conference – Canada’s Third Ocean 3 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] The Editor’s Desk 4 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] The Bridge 4 The Front Desk 6 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] NAC Regalia Sales 6 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

Back Issues Available

INRO Available Back Issues of Warship International August 2015 VOL. 3, No. 1 1966 Featuring: Losses – Royal Italian Navy 1915-18; Lexington Battle Cruisers; The Early Jean Barts; Soviet Potpourri.. Vol. 20, No. 3 1983 Featuring: The Development of “A” Class Cruisers in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Part VI. Vol. 21, No. 1 1984 Featuring: NRC/INRO the First 20 Years; An INRO Library; Early Spanish Steam Warships, Part II; Exterior Ballistics with Microcomputers. Vol. 21, No. 2 1984 Featuring: Sparrows Among the Hawks; Elisabeta; Elisabeta and Her Armament; New Developments in the Soviet Navy; The Spanish Navy of 1898; Battleships, A Vulnerable Anachronism? Vol. 21, No. 3 1984 Featuring: The Development of the “A Class” Cruisers in the Japanese Navy, Part VII. Vol. 23, No. 3 1986 Featuring: The Thai Navy; The U.S. Fleet at the New York World’s Fair, 1939; The Last, Strange Cruise of UB-88. Vol. 24, No. 1 1987 Featuring: Phantom Fleet – The Confederacy’s Unclaimed European Warships; Sous La Crois De Lorraine (Under the Cross of Lorraine); Japanese Naval Construction, 1915-45; HMNZS Tui; The Mystery of the Austro-Hungarian submarine U-30. Vol. 24, No. 2 1987 Featuring: The Loss of HMS Hood – A Re-examination; Developments in the Soviet Navy; The fate of the Chinese Torpedo Gunboat Fei Ting; The Fate of the Four Chinese Torpedo Boat Destroyers. Vol. 24, No. 3 1987 Featuring: U.S. Navy in WW II – A Basic Bibliography; A Day at the New York Navy Yard; 50 Years of Army Dredge Boats; The Attack on the USS Stark; Battleships – Impressions of a Dinosaur; Submarine Hull design and Diving Depths Between the Wars. -

Naval Documents of the American Revolution

Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 4 AMERICAN THEATRE: Feb. 19, 1776–Apr. 17, 1776 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Feb. 1, 1776–May 25, 1776 AMERICAN THEATRE: Apr. 18, 1776–May 8, 1776 Part 7 of 7 United States Government Printing Office Washington, 1969 Electronically published by American Naval Records Society Bolton Landing, New York 2012 AS A WORK OF THE UNITED STATES FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THIS PUBLICATION IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN. MAY 1776 1413 5 May (Sunday) JOURNAL OF H.M. SLOOPHunter, CAPTAINTHOMAS MACKENZIE May 1776 ' Remarks &c in Quebec 1776 Sunday 5 at 5 A M Arrived here his Majestys Sloop surprize at 8 the surprise & Sloop Martin with part of the 29th regt landed with their Marines Light Breezes & fair Sally'd out & drove the rebels off took at different places several pieces of Cannon some Howitzers & a Quantity of Ammunition 1. PRO, Admiralty 511466. JOURNALOF H.M.S. Surprize, CAPTAINROBERT LINZEE May 1776 Runing up the River [St. Lawrence] - Sunday 5. at 4 AM. Weigh'd and came to sail, at 9 Got the Top Chains up, and Slung the yards the Island of Coudre NEBE, & Cape Tor- ment SW1/2W. off Shore 1% Mile. At 10 Came too with the Best Bower in 11 fms. of Water, Veer'd to 1/2 a Cable. at 11 Employ'd racking the Lanyards of the Shrouds, and getting every thing ready for Action. Most part little Wind and Cloudy, Remainder Modre and hazey, at 2 [P.M.] Weigh'd and came to sail, Set Studding sails, nock'd down the Bulk Heads of the Cabbin at 8 PM Came too with the Best Bower in 13 £ms Veer'd to % of a Cable fir'd 19 Guns Signals for the Garrison of Quebec. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Battleships and Dividends: The Rise of Private Armaments Firms in Great Britain and Italy, c. 1860-1914 MARCHISIO, GIULIO How to cite: MARCHISIO, GIULIO (2012) Battleships and Dividends: The Rise of Private Armaments Firms in Great Britain and Italy, c. 1860-1914, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7323/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Battleships and Dividends: The Rise of Private Armaments Firms in Great Britain and Italy, c. 1860-1914 Giulio Marchisio This thesis analyses the rise of private armaments firms in Great Britain and in Italy from mid-19th century to the outbreak of the First World War, with a focus on naval armaments and military shipbuilding. During this period, the armaments industry underwent a radical transformation, moving from being based on public-owned arsenals and yards to being based on private firms – the system of military procurement prevalent today. -

At the Double a Snowy Douaumont

JOURNAL February 48 2013 At the Double A snowy Douaumont Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All An interesting article in the Times caught my eye a couple of weeks ago. Carrying the heading: ‘Dramatic boost for campaign to honour first black officer’, it covers the life of Walter Tull, a coloured professional footballer with Tottenham Hotspur and Northampton Town, who joined up in the ranks at the beginning of the War, enlisting in the 17th Battalion (1st Footballer’s), Middlesex Regiment as it came to be known, and was later commissioned, before being killed in March, 1918. The campaign referred to, asks the government to award him a posthumous Military Cross for his bravery, and indeed, he had been recommended for the MC for courageous acts undertaken some time before his death. But, one presumes that, given that a unit could only receive so many awards in a month, more meritorious acts were recognised, and so Walter Tull’s gallantry sadly went unrewarded. The award of a posthumous MC to a very brave man does sound like a nice idea, but in these specific circumstances is it not woolly-headed? Politically correct even? I think that it is both, and would set an unwelcome precedent. With the rationing of medals, whoever had to decide who should receive the six, shall we say, awards from ten recommendations had to make a judgement call, and these decisions were made at Brigade and Division level. -

Coastal Command in the Second World War

AIR POWER REVIEW VOL 21 NO 1 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Professor John Buckley Biography: John Buckley is Professor of Military History at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. His books include The RAF and Trade Defence 1919-1945 (1995), Air Power in the Age of Total War (1999) and Monty’s Men: The British Army 1944-5 (2013). His history of the RAF (co-authored with Paul Beaver) will be published by Oxford University Press in 2018. Abstract: From 1939 to 1945 RAF Coastal Command played a crucial role in maintaining Britain’s maritime communications, thus securing the United Kingdom’s ability to wage war against the Axis powers in Europe. Its primary role was in confronting the German U-boat menace, particularly in the 1940-41 period when Britain came closest to losing the Battle of the Atlantic and with it the war. The importance of air power in the war against the U-boat was amply demonstrated when the closing of the Mid-Atlantic Air Gap in 1943 by Coastal Command aircraft effectively brought victory in the Atlantic campaign. Coastal Command also played a vital role in combating the German surface navy and, in the later stages of the war, in attacking Germany’s maritime links with Scandinavia. Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors concerned, not necessarily the MOD. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without prior permission in writing from the Editor. 178 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR introduction n March 2004, almost sixty years after the end of the Second World War, RAF ICoastal Command finally received its first national monument which was unveiled at Westminster Abbey as a tribute to the many casualties endured by the Command during the War. -

Jabberwock No 85

BERWO JAB CK The Magazine of the Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum IN THISIN THIS EDITION: EDITION: • Memoirs of Captain Keith Leppard and Sqn Ldr Maurice Biggs • Peter Twiss • Christmas Lunch notice • Hawker Sea Fury detail • The first angled deck • HMS Engadine at theBattle of Jutland • Society Visit to the Meteorological Office • Book Review - “Air War in the Mediterranean” PLUS: All the usual features; news from the Museum, snippets from Council meetings, monthly talks programme, latest membership numbers... No. 85 November 2016 No. 85 November 2016 Published by The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Published by The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Jabberwock No 85. November 2016 Patron: Rear Admiral A R Rawbone CB, AFC, RN President: Gordon Johnson FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM RNAS Yeovilton Somerset BA22 8HT Telephone: 01935 840565 SOFFAAM email: [email protected] SOFFAAM website: fleetairarmfriends.org.uk Registered Charity No. 280725 Sunset - HMS Illustrious 1 Jabberwock No 85. November 2016 The Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum Admission Vice Presidents Members are admitted to the Museum Rear Admiral A R Rawbone CB, AFC, RN free of charge, on production of a valid F C Ott DSC BSc (Econ) membership card. Members may be Lt Cdr Philip (Jan) Stuart RN accompanied by up to three guests (one David Kinloch guest only for junior members) on any Derek Moxley one visit, each at a reduced entrance Gerry Sheppard fee, currently 50% of the standard price. Members are also allowed a 10% Bill Reeks discount on goods purchased from the shop. -

Naval Dockyards Society

20TH CENTURY NAVAL DOCKYARDS: DEVONPORT AND PORTSMOUTH CHARACTERISATION REPORT Naval Dockyards Society Devonport Dockyard Portsmouth Dockyard Title page picture acknowledgements Top left: Devonport HM Dockyard 1951 (TNA, WORK 69/19), courtesy The National Archives. Top right: J270/09/64. Photograph of Outmuster at Portsmouth Unicorn Gate (23 Oct 1964). Reproduced by permission of Historic England. Bottom left: Devonport NAAFI (TNA, CM 20/80 September 1979), courtesy The National Archives. Bottom right: Portsmouth Round Tower (1843–48, 1868, 3/262) from the north, with the adjoining rich red brick Offices (1979, 3/261). A. Coats 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the MoD. Commissioned by The Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England of 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, EC1N 2ST, ‘English Heritage’, known after 1 April 2015 as Historic England. Part of the NATIONAL HERITAGE PROTECTION COMMISSIONS PROGRAMME PROJECT NAME: 20th Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth (4A3.203) Project Number 6265 dated 7 December 2012 Fund Name: ARCH Contractor: 9865 Naval Dockyards Society, 44 Lindley Avenue, Southsea, PO4 9NU Jonathan Coad Project adviser Dr Ann Coats Editor, project manager and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Davies Editor and reviewer, project executive and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Evans Devonport researcher David Jenkins Project finance officer Professor Ray Riley Portsmouth researcher Sponsored by the National Museum of the Royal Navy Published by The Naval Dockyards Society 44 Lindley Avenue, Portsmouth, Hampshire, PO4 9NU, England navaldockyards.org First published 2015 Copyright © The Naval Dockyards Society 2015 The Contractor grants to English Heritage a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, perpetual, irrevocable and royalty-free licence to use, copy, reproduce, adapt, modify, enhance, create derivative works and/or commercially exploit the Materials for any purpose required by Historic England. -

Dreadnoughts and Crosses – How Battleships Brought the ANZACS to Gallipoli

Dreadnoughts and Crosses – How battleships brought the ANZACS to Gallipoli Part 1 – The South American Arena HMS Dreadnought: The revolutionary fighting machine, launched in 1906, whose namesakes eventually brought the ANZACS to Gallipoli. Source: "HMS Dreadnought 1906 H61017" by U.S. Navy - U.S. Naval Historical Center. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMS_Dreadnought_1906_H61017 jpg#/media/File:HMS_Dreadnought_1906_H61017.jpg 4.00 am on Sunday, 20 December 2015 marked the centenary of the last man leaving ANZAC cove at the end of the Gallipoli campaign. By the time the Allies evacuated the peninsula after just over eight months of fighting, each side had lost just under 60,000 dead. By the military standards of other battles in World War I these losses were small. Despite this, for three combatant countries, the young dominions of Australia and New Zealand and the yet to be born Turkish Republic, the battle was a seminal national event. For this reason the details of the battle itself are well known and have been repeatedly re- enacted in print, video and film. What has received slightly less attention is how the Allies and the Turkish (Ottoman) Empire came to be enemies in the first place. The Ottoman Empire was not part of the deadly twin daisy chains of alliances and obligations that dragged all the other great imperial powers of Europe into an involuntary state of war in the days after the Austro Hungarian Empire chose to attack Serbia. The Ottomans had the luxury of choice. They could join the Allies, or they could join the Central Powers. -

Revisiting and Early Naval Incident of the Cold War: Archaeological Identification of the Bow of HMS Volage Sunk During the Corf

Notes 1 During the 2008 field season the bay of Porto Polermo and its entrance was completed. 2 Multibeam data was acquired through Kongsberg’s SIS software, processed in CARIS HIPS/SIPS, and modeled in IVS Fledermaus software for anomaly analysis. All acquisition and processing of data was performed by surveyors contracted from Highland Geo Solutions Inc. of Fredericton, NB, Canada. 3 IVS kindly provided a prototype software module that allowed the tracking of all vessels within James P. Delgado INA the 3-D models of the seafloor in Jeffery Royal RPM Nautical Foundation Fledermaus. Adrian Anastasi University of Tirana 4 Although it is not clear from the evidence if this was the scuttled Austro-Hungarian submarine U-72, the German U-24, or whether a Revisiting and Early Naval Incident of the Cold British submarine (possibly the H2) that was also lost in the area. War: Archaeological Identification of the Bow 5 Not only were modern war craft a common find, but a spent of HMS Vol ag e Sunk During the Corfu missile was also found in target confirmation. There have been Channel Incident of October 22, 1946 many tons of munitions from the HMS Volage, various 20th-century conflicts from Pingbosun, removed from Montengro’s waters Destroyers by the RDMC; however, all of the Second Album, finds discussed here were at depths Picasa. over 60 m. 6 The heavy concentration of Roman and Late Roman-era amphoras littering the seafloor, some of which are intrusive on Archaic-Hellenist Greek wreck sites, probably led to confusion. 7 Lindhagen 2009. -

60 Years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 - 2018 Part 4: Europe & Canada Peter Lobner July 2018 1 Foreword In 2015, I compiled the first edition of this resource document to support a presentation I made in August 2015 to The Lyncean Group of San Diego (www.lynceans.org) commemorating the 60th anniversary of the world’s first “underway on nuclear power” by USS Nautilus on 17 January 1955. That presentation to the Lyncean Group, “60 years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955 – 2015,” was my attempt to tell a complex story, starting from the early origins of the US Navy’s interest in marine nuclear propulsion in 1939, resetting the clock on 17 January 1955 with USS Nautilus’ historic first voyage, and then tracing the development and exploitation of marine nuclear power over the next 60 years in a remarkable variety of military and civilian vessels created by eight nations. In July 2018, I finished a complete update of the resource document and changed the title to, “Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018.” What you have here is Part 4: Europe & Canada. The other parts are: Part 1: Introduction Part 2A: United States - Submarines Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships Part 3A: Russia - Submarines Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications Part 5: China, India, Japan and Other Nations Part 6: Arctic Operations 2 Foreword This resource document was compiled from unclassified, open sources in the public domain. I acknowledge the great amount of work done by others who have published material in print or posted information on the internet pertaining to international marine nuclear propulsion programs, naval and civilian nuclear powered vessels, naval weapons systems, and other marine nuclear applications. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A.