David Hardiman . Submitted for the Degree of Doctor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

GUJARAT UNIVERSITY Hisotry M.A

Publication Department, Guajrat University [1] GUJARAT UNIVERSITY Hisotry M.A. Part-I Group - 'A' In Force from June 2003, Compulsory Paper-I (Historiography, Concept, Methods and Tools) (100 Marks : 80 Lectures) Unit-1 : Meaning and Scope of Hisotry (a) Meaning of History and Importance of its study. (b) Nature and Scope of History (c) Collection and selection of sources (data); evidence and its transmission; causation; and 'Historicism' Unit-2 : History and allied Disciplines (a) Archaeology; Geography; Numasmatics; Economics; Political Science; Sociology and Literature. Unit-3 : Traditions of Historical Writing (a) Greco-Roman traditions (b) Ancient Indian tradition. (c) Medieval Historiography. (d) Oxford, Romantic and Prussion schools of Historiography Unit-4 : Major Theories of Hisotry (a) Cyclical, Theological, Imperalist, Nationalist, and Marxist Unit-5 : Approaches to Historiagraphy (a) Evaluation of the contribution to Historiography of Ranke and Toynbee. (b) Assessment of the contribution to Indian Historiography of Jadunath Sarkar, G.S. Sardesai and R.C. Majumdar, D.D. Kosambi. (c) Contribution to regional Historiography of Bhagvanlal Indraji and Shri Durga Shankar Shastri. Paper-I Historiography, Concept, Methods and Tools. Suggested Readings : 1. Ashley Montagu : Toynbee and History, 1956. 2. Barnes H.E. : History of Historical Writing, 1937, 1963 3. Burg J.B. : The Ancient Greek Historians, 1909. 4. Car E.H. : What is History, 1962. 5. Cohen : The meaning of Human History, 1947, 1961. 6. Collingwood R.G. : The Idea of History, 1946. 7. Donagan Alan and Donagan Barbara : Philosophy of History, 1965 8. Dray Will Iam H : Philosophy of History, 1964. 9. Finberg H.P.R. (Ed.) : Approaches to History, 1962. -

Sardar Patel's Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha

Sardar Patel’s Role in Nagpur Flag Satyagraha Dr. Archana R. Bansod Assistant Professor & Director I/c (Centre for Studies & Research on Life & Works of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (CERLIP) Vallabh Vidya Nagar, Anand, Gujarat. Abstract. In March 1923, when the Congress Working Committee was to meet at Jabalpur, the Sardar Patel is one of the most foremost figures in the Municipality passed a resolution similar to the annals of the Indian national movement. Due to his earlier one-to hoist the national flag over the Town versatile personality he made many fold contribution to Hall. It was disallowed by the District Magistrate. the national causes during the struggle for freedom. The Not only did he prohibit the flying of the national great achievement of Vallabhbhai Patel is his successful flag, but also the holding of a public meeting in completion of various satyagraha movements, particularly the Satyagraha at Kheda which made him a front of the Town Hall. This provoked the th popular leader among the people and at Bardoli which launching of an agitation on March 18 . The earned him the coveted title of “Sardar” and him an idol National flag was hoisted by the Congress for subsequent movements and developments in the members of the Jabalpur Municipality. The District Indian National struggle. Magistrate ordered the flag to be pulled down. The police exhibited their overzealousness by trampling Flag Satyagraha was held at Nagput in 1923. It was the the national flag under their feet. The insult to the peaceful civil disobedience that focused on exercising the flag sparked off an agitation. -

Members – List.Pdf

Name Address Pinalbhai Punambhai Patel Near Dairy, Lambhavel, Anand Axit Manubhai Patel Nr. Gayatrimandir, Kasor, Anand Vipul Babubhai Patel Amba Chowk, Boriyavi, Anand Chintan Dipakbhai Patel Dr. Khadki, Samarkha, Anand Hardik Pankajbhai Patel Pipla pol, Lambhavel, Anand Denish Dilipbhai Patel Patel Society, Valasan, Anand Nirmal Maheshbhai Patel Moti Khadki, Vansol, Anand Akash Dipakbhai Patel Piplapol, Lambhavel, Anand Jigar Rajnikant Patel Mahadev Khadki, Lambhavel, Anand Ronak Nikunjbhai Patel Tran Khadki, Valasan, Anand Sagar Bhanubhai Patel Moti Khadki, Petli, Vaso Vishal Ashokbhai Inamdar Inamdar Street, Valasan, Anand Paresh Pujabhai Patel Amba Chowk, Jitodiya, Anand Chandresh Chandubhai Patel Nr. Radha Krushna Mandir Jitodiya, Anand Ramendra Dhanjibhai Patel Valasan, Anand Tarun Ramanbhai Patel Nr. Mota Mahadev, Valasan, Anand Vikas Ganshyambhai Patel Piplavali Khadki, Valasan, Anand Ashok Sankarbhai Patel 11, Tulip Society, Anand Mihir Dilipbhai Patel Near Primary School, Lambhavel, Anand Rakesh Balendrabhai Patel Nr. Swaminarayan Mandir, Piplata Bhavin Vinubhai Patel Jol, Anand Krupesh Nikunjbhai Patel Tran Khadki, Valasan, Anand Mayurbhai Anilbhai Patel 71, Kartavya, Lambhavel, Anand Dipalkumar Vithhalbhai Patel Moti Khadki, Anklav, Anand. Sandipkumar Kanchanbhai Patel Kakanipol, sandesar, Anand Rakeshkumar Anilbhai Patel Nava Ghara, Karamsad, Anand Mukesh Manubhai Patel Swaminarayan Soc, Valasan, Anand Laxmanbhai Ambalalbhai Patel Kakanipol, Sandesar, Anand Shaileshbhai Chimanbhai Patel Motikhadki, Anklav, Anand Dwarkadas -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

Seats Vacant Due to Non-Allotment in BE 2020 Round-02

Seats Vacant due to non-allotment in BE 2020 Round-02 Inst_Name Course_name Total Vacant A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING 53 50 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad CIVIL ENGINEERING 27 22 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 27 24 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION ENGG. 27 23 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad FOOD PROCESSING & TECHNOLOGY 53 7 A.D.Patel Institute Of Tech.,Karamsad MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 79 75 ADANI INSTITUTE OF INFRASTRUCTURE ENGINEERING,AHMEDABAD Civil & Infrastructure Engineering 53 21 ADANI INSTITUTE OF INFRASTRUCTURE ENGINEERING,AHMEDABAD ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 53 37 ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF AERONAUTICAL ENGINEERING 90 82 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERING 30 15 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF CIVIL ENGINEERING 30 28 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 60 55 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 111 18 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD ADITYA SILVER OAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WITHIN LIMITS OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 90 90 AHMEDABAD MUNICIPAL CORPORATION) AHMEDABAD Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad AUTOMOBILE ENGINEERING 26 25 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad CIVIL ENGINEERING 19 17 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 19 18 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION ENGG. 19 19 Ahmedabad Institute Of Tech, Ahmedabad MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 38 36 Alpha College Of Engg. & Tech., Khatraj, Kalol CIVIL ENGINEERING 75 75 Alpha College Of Engg. -

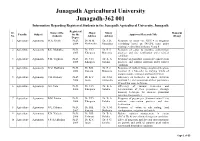

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

Rajgors Auction 19

World of Coins Auction 19 Saturday, 28th June 2014 6:00 pm at Rajgor's SaleRoom 6th Floor, Majestic Shopping Center, Near Church, 144 J.S.S. Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 VIEWING (all properties) Monday 23 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Category LOTS Tuesday 24 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Wednesday 25 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Ancient Coins 1-31 Thursday 26 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Hindu Coins of Medieval India 32-38 Friday 27 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Sultanates Coins of Islamic India 39-49 Saturday 28 June 2014 11:00 am - 4:00 pm Coins of Mughal Empire 50-240 6th Floor, Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, Coins of Independent Kingdoms 241-251 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Princely States of India 252-310 Easy to buy at Rajgor's Conditions of Sale Front cover: Lot 55 • Back cover: Lot 14 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s CONDITIONS OF SALE This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. Rajgor's Advisory Panel Corporate Office 6th Floor, Majestic Shopping Center, Prof. Dr. A. P. Jamkhedkar Director (Retd.), Near Church, 144 J.S.S. -

Gadre 1943.Pdf

- Sri Pratapasimha Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantha-maia MEMOIR No. II. IMPORTANT INSCRIPTIONS FROM THE BARODA STATE. * Vol. I. Price Rs. 5-7-0 A. S. GADRE INTRODUCTION I have ranch pleasure in writing a short introduction to Memoir No, II in 'Sri Pratapsinh Maharaja Rajyabhisheka Grantharnala Series', Mr, Gadre has edited 12 of the most important epigraphs relating to this part of India some of which are now placed before the public for the first time. of its These throw much light on the history Western India and social and economic institutions, It is hoped that a volume containing the Persian inscriptions will be published shortly. ' ' Dilaram V. T, KRISHNAMACHARI, | Baroda, 5th July 1943. j Dewan. ii FOREWORD The importance of the parts of Gujarat and Kathiawad under the rule of His Highness the Gaekwad of Baroda has been recognised by antiquarians for a the of long time past. The antiquities of Dabhoi and architecture Northern the Archaeo- Gujarat have formed subjects of special monographs published by of India. The Government of Baroda did not however realise the logical Survey of until a necessity of establishing an Archaeological Department the State nearly decade ago. It is hoped that this Department, which has been conducting very useful work in all branches of archaeology, will continue to flourish under the the of enlightened rule of His Highness Maharaja Gaekwad Baroda. , There is limitless scope for the activities of the Archaeological Department in Baroda. The work of the first Gujarat Prehistoric Research Expedition in of the cold weather of 1941-42 has brought to light numerous remains stone age and man in the Vijapuf and Karhi tracts in the North and in Sankheda basin. -

The Tyabji Clan—Urdu As a Symbol of Group Identity by Maren Karlitzky University of Rome “La Sapienza”

The Tyabji Clan—Urdu as a Symbol of Group Identity by Maren Karlitzky University of Rome “La Sapienza” T complex issue of group identity and language on the Indian sub- continent has been widely discussed by historians and sociologists. In particular, Paul Brass has analyzed the political and social role of language in his study of the objective and subjective criteria that have led ethnic groups, first, to perceive themselves as distinguished from one another and, subsequently, to demand separate political rights.1 Following Karl Deutsch, Brass has underlined that the existence of a common language has to be considered a fundamental token of social communication and, with this, of social interaction and cohesion. 2 The element of a “national language” has also been a central argument in European theories of nationhood right from the emergence of the concept in the nineteenth century. This approach has been applied by the English-educated élites of India to the reality of the Subcontinent and is one of the premises of political struggles like the Hindi-Urdu controversy or the political claims put forward by the Muslim League in promoting the two-nations theory. However, in Indian society, prior to the socio-political changes that took place during the nineteenth century, common linguistic codes were 1Paul R. Brass has studied the politics of language in the cases of the Maithili movement in north Bihar, of Urdu and the Muslim minority in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and of Panjabi in the Hindu-Sikh conflict in Punjab. Language, Religion and Politics in North India (London: Cambridge University Press, ). -

Notes on the Famine Tour

I 1 ryfipfy) <fitr£ NOTES ON THE FAMINE TOUR W %04><^t^J?' Js*s ayt 4 U- ztU «f ' &<?,'je^s&t a^& a- 1 y. /3-a*^« V S/ /f* LABOURERS AT WORK [Frontispiece. ON THE NOTESFAMINE TOUR BY HIS HIGHNESS THE MAHARAJA GAEKWAR PRIVATELY PRINTED 1 90 1 IQAN SFACK Printed for MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited, London By R. & R. Clark, Limited, Edinburgh 25 CONTENTS I.—KADI DIVISION 1. Kadi Division ..... 3 2. Places visited during the Tour . 3 3. Codification of Famine Rules 4 4. Tagavi for Maintenance 5 5. Tagavi to Ekankadi and Fartaankadi Village-holders 6 6. Tagavi to Coppersmiths at Visnagar 6 7. Private Charity in Kadi 6 8. Gyarmi and Sadavarat Institutions utilised for Relie Purposes ..... 7 9. Grants to prevent Death by Starvation . 8 10. Dispensation of Gratuitous Relief at Harij 9 11. Orphanage at Mehsana .... 9 12. Lying-in Arrangements at the Hospitals for Destitute Women . 10 13. Relief-works ..... 10 14. Too near the Homes of the Rayats 10 Their Number 1 1 15. large .... 16. Reduction of Works .... 12 17. Nature of these Works .... 13 18. Gangadi Tank, Task System H 19. Imposition of Tasks and Classification of Labourers »4 20. Second Class of Labourers '5 v a 2 8532 FAMINE TOUR PAGE 21. Complaints made to me by Labourers l6 22. Shortcomings of Relief Officials 18 23. The Complaints of the Labourers relieved l 9 20 24. Delay in the Payment of Wages 20 25. How remedied 26. Excessive Tasks 21 Babashahi Coin 21 27. Low Wages ; 28.