Layout for the Title Page of a Mphil/Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Do Students Know and Understand About the Holocaust? Evidence from English Secondary Schools

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster, Alice Pettigrew, Andy Pearce, Rebecca Hale Centre for Holocaust Education Centre Adrian Burgess, Paul Salmons, Ruth-Anne Lenga Centre for Holocaust Education What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Cover image: Photo by Olivia Hemingway, 2014 What do students know and understand about the Holocaust? Evidence from English secondary schools Stuart Foster Alice Pettigrew Andy Pearce Rebecca Hale Adrian Burgess Paul Salmons Ruth-Anne Lenga ISBN: 978-0-9933711-0-3 [email protected] British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP record is available from the British Library All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permissions of the publisher. iii Contents About the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education iv Acknowledgements and authorship iv Glossary v Foreword by Sir Peter Bazalgette vi Foreword by Professor Yehuda Bauer viii Executive summary 1 Part I Introductions 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Methodology 23 Part II Conceptions and encounters 35 3. Collective conceptions of the Holocaust 37 4. Encountering representations of the Holocaust in classrooms and beyond 71 Part III Historical knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust 99 Preface 101 5. Who were the victims? 105 6. -

Holocaust/Shoah the Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-Day Poland

NOW AVAILABLE remembrance a n d s o l i d a r i t y Holocaust/Shoah The Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-day Poland in 20 th century european history Ways of Survival as Revealed in the Files EUROPEAN REMEMBRANCE of the Ghetto Courts and Police in Lithuania – LECTURES, DISCUSSIONS, remembrance COMMENTARIES, 2012–16 and solidarity in 20 th This publication features the century most significant texts from the european annual European Remembrance history Symposium (2012–16) – one of the main events organized by the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity in Gdańsk, Berlin, Prague, Vienna and Budapest. The 2017 issue symposium entitled ‘Violence in number the 20th-century European history: educating, commemorating, 5 – december documenting’ will take place in Brussels. Lectures presented there will be included in the next Studies issue. 2016 Read Remembrance and Solidarity Studies online: enrs.eu/studies number 5 www.enrs.eu ISSUE NUMBER 5 DECEMBER 2016 REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY EDITED BY Dan Michman and Matthias Weber EDITORIAL BOARD ISSUE EDITORS: Prof. Dan Michman Prof. Matthias Weber EDITORS: Dr Florin Abraham, Romania Dr Árpád Hornják, Hungary Dr Pavol Jakubčin, Slovakia Prof. Padraic Kenney, USA Dr Réka Földváryné Kiss, Hungary Dr Ondrej Krajňák, Slovakia Prof. Róbert Letz, Slovakia Prof. Jan Rydel, Poland Prof. Martin Schulze Wessel, Germany EDITORIAL COORDINATOR: Ewelina Pękała REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY PUBLISHER: European Network Remembrance and Solidarity ul. Wiejska 17/3, 00–480 Warszawa, Poland www.enrs.eu, [email protected] COPY-EDITING AND PROOFREADING: Caroline Brooke Johnson PROOFREADING: Ramon Shindler TYPESETTING: Marcin Kiedio GRAPHIC DESIGN: Katarzyna Erbel COVER DESIGN: © European Network Remembrance and Solidarity 2016 All rights reserved ISSN: 2084–3518 Circulation: 500 copies Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag. -

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

Resistance in the Ghettos

Say 76 Resistance in the Ghettos Tim Say While some scholars like Raul Hilberg have argued that there was little resistance from Jews during the Holocaust, the large amount of evidence available has demonstrated that this is false, and that Jews resisted in many different ways. Specifically in the ghettos throughout Europe, resistance took many different forms which can be categorized as either active or passive resistance. The most well-known examples of resistance are the various uprisings, such as in the Warsaw ghetto, though it also includes other active forms such as raids to attack German supply lines or train stations. Active resistance was not common throughout the ghettos, however, as it created controversy because of the very real threat of reprisals from the Germans, who had no compunction about killing dozens of Jews in retaliation for one German death. This threat divided many ghettos about whether or not active resistance was the appropriate action to take. The concept of passive resistance was perhaps more important, as it was much more prevalent throughout the ghettos and affected the everyday lives of the majority of the inhabitants. It included life giving examples such as the smuggling of food, as well as more psychological examples such as religious education, or cultural activities like music and theatre. These types of examples are especially important because they specifically address the German strategy of demoralizing the inhabitants of the ghettos. Additionally, they serve to demonstrate that resistance was not only common throughout the ghettos, but was integral in maintaining the health and identity of the Jewish community in the face of the desperate circumstances. -

Jewish Behavior During the Holocaust

VICTIMS’ POLITICS: JEWISH BEHAVIOR DURING THE HOLOCAUST by Evgeny Finkel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 07/12/12 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Yoshiko M. Herrera, Associate Professor, Political Science Scott G. Gehlbach, Professor, Political Science Andrew Kydd, Associate Professor, Political Science Nadav G. Shelef, Assistant Professor, Political Science Scott Straus, Professor, International Studies © Copyright by Evgeny Finkel 2012 All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the encouragement, support and help of many people to whom I am grateful and feel intellectually, personally, and emotionally indebted. Throughout the whole period of my graduate studies Yoshiko Herrera has been the advisor most comparativists can only dream of. Her endless enthusiasm for this project, razor- sharp comments, constant encouragement to think broadly, theoretically, and not to fear uncharted grounds were exactly what I needed. Nadav Shelef has been extremely generous with his time, support, advice, and encouragement since my first day in graduate school. I always knew that a couple of hours after I sent him a chapter, there would be a detailed, careful, thoughtful, constructive, and critical (when needed) reaction to it waiting in my inbox. This awareness has made the process of writing a dissertation much less frustrating then it could have been. In the future, if I am able to do for my students even a half of what Nadav has done for me, I will consider myself an excellent teacher and mentor. -

Intimacy Imprisoned: Intimate Human Relations in The

INTIMACY IMPRISONED: INTIMATE HUMAN RELATIONS IN THE HOLOCAUST CAMPS In fulfillment of EUH 6990 Dr. Daniel E. Miller 1 December 2000 Donna R. Fluharty 2 Each person surviving the Holocaust has their own personal narrative. A great number of these narratives have been written; many have been published. It is important for personal accounts to be told by each survivor, as each narrative brings a different perspective to the combined history. Knowing this, I dedicate my research to the narratives I was unable to read, whether they were simply unavailable or, unfortunately, unwritten. More importantly, this research is dedicated to those whose stories will never be told. 3 In his book Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl states that a human being is able to withstand any condition if there is sufficient meaning to his existence, a theme which permeates the entire work. 1 For a significant number of people, the right to this search for meaning was denied by a Holocaust which took the lives of an undetermined number of European Jews, war criminals, homosexuals, Gypsies, children, and mentally or physically handicapped persons. This denial of humanness was an essential component of Adolph Hitler’s plan to elevate the Aryan nation and rid the world of undesirables. In spite of laws which dictated human associations, through the triumph of the human spirit, certain prisoners of the Nazi ghettos, labor camps, and death camps were able to survive. Many of these survivors have graced the academic and public world with a written account of their experiences as prisoners of the Nazis. -

Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2001 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, March 2004 Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi Laszlo Berkowits, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Tim Cole, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by István Deák, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Eva Hevesi Ehrlich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Charles Fenyvesi; Copyright © 2001 by Paul Hanebrink, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Albert Lichtmann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by George S. Pick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum In Charles Fenyvesi's contribution “The World that Was Lost,” four stanzas from Czeslaw Milosz's poem “Dedication” are reprinted with the permission of the author. Contents -

Study Guide REFUGE

A Guide for Educators to the Film REFUGE: Stories of the Selfhelp Home Prepared by Dr. Elliot Lefkovitz This publication was generously funded by the Selfhelp Foundation. © 2013 Bensinger Global Media. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements p. i Introduction to the study guide pp. ii-v Horst Abraham’s story Introduction-Kristallnacht pp. 1-8 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 8-9 Learning Activities pp. 9-10 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Kristallnacht pp. 11-18 Enrichment Activities Focusing on the Response of the Outside World pp. 18-24 and the Shanghai Ghetto Horst Abraham’s Timeline pp. 24-32 Maps-German and Austrian Refugees in Shanghai p. 32 Marietta Ryba’s Story Introduction-The Kindertransport pp. 33-39 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 39 Learning Activities pp. 39-40 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Sir Nicholas Winton, Other Holocaust pp. 41-46 Rescuers and Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust Marietta Ryba’s Timeline pp. 46-49 Maps-Kindertransport travel routes p. 49 2 Hannah Messinger’s Story Introduction-Theresienstadt pp. 50-58 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 58-59 Learning Activities pp. 59-62 Enrichment Activities Focusing on The Holocaust in Czechoslovakia pp. 62-64 Hannah Messinger’s Timeline pp. 65-68 Maps-The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia p. 68 Edith Stern’s Story Introduction-Auschwitz pp. 69-77 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 77 Learning Activities pp. 78-80 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Theresienstadt pp. 80-83 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Auschwitz pp. 83-86 Edith Stern’s Timeline pp. -

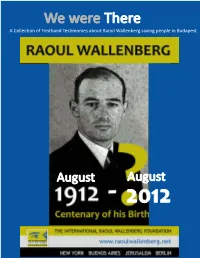

We Were There. a Collection of Firsthand Testimonies

We were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies about Raoul Wallenberg saving people in Budapest August August 2012 We Were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies About Raoul Wallenberg Saving People in Budapest 1 Contributors Editors Andrea Cukier, Daniela Bajar and Denise Carlin Proofreader Benjamin Bloch Graphic Design Helena Muller ©2012. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) Copyright disclaimer: Copyright for the individual testimonies belongs exclusively to each individual writer. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) claims no copyright to any of the individual works presented in this E-Book. Acknowledgments We would like to thank all the people who submitted their work for consideration for inclusion in this book. A special thanks to Denise Carlin and Benjamin Bloch for their hard work with proofreading, editing and fact-checking. 2 Index Introduction_____________________________________4 Testimonies Judit Brody______________________________________6 Steven Erdos____________________________________10 George Farkas___________________________________11 Erwin Forrester__________________________________12 Paula and Erno Friedman__________________________14 Ivan Z. Gabor____________________________________15 Eliezer Grinwald_________________________________18 Tomas Kertesz___________________________________19 Erwin Koranyi____________________________________20 Ladislao Ladanyi__________________________________22 Lucia Laragione__________________________________24 Julio Milko______________________________________27 -

Newsletter of the World Federation of Jewish Child Survivors of the Holocaust

Newsletter of the World Federation of Jewish Child Survivors of the Holocaust Mishpocha! A link among child survivors around the world Summer 2008 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Hidden Child Foundation/ADL, NY President’s Message KTA – Kindertransport Assn., NY Friends and Alumni of OSE-USA, MD ----------------------- Dear Friends Near and Far, Aloumim, Israel Assn. of Children of the Holocaust in Poland Our Child Survivor Family has gr own considerably over the last Assn. of Child Survivors in Croatia Assn. of Holocaust Survivors in Sweden few years and we heard from many of you telling about how you Assn. of Jewish War Children – Amsterdam enjoyed the “bonding” experience at our last conference in Jerusalem. Assn. of Unknown Children, Netherlands Child Survivor Group of Argentina Perhaps this was the more so because we are all coming to an age when our life Child Survivors Group of British Columbia situa tions are changing once again: our children are on their own, often at some Child Survivor Group of Sydney, Australia Child Survivors’ Assn. of Great Britain distance from us; some of us have no children, and our physical state is, unfortunately, Child-Survivors-Deutschland e.V. not always the best. Our need for the caring friendship of our fellow Child Survivors is Child Survivors, Hungary Child Survivors/Hidden Children of Toronto ever greater. I am taking this opportunity to ask all of you to “be there” for each other; Children of The Shoah, Figli Della Shoah, to call, to show caring, to offer a shoulder to cry on, to utter a loving word. In giving of Italy European Assn. -

9Th Graders Digitally Meet with Two Holocaust Survivors

9th graders digitally meet with two Holocaust survivors This year, the school library and Bill Brown have served to better the education of our children in many ways, most recently by facilitating a relationship with the Holocaust Memorial and Tolerance Center of Nassau County. Through this relationship, 9th grade World Studies students (led by teacher Chris Mosher) have had the opportunity to teleconference with a Holocaust survivor for the past 4 years. This year, on May 26 and May 28, we continued that tradition by meeting two Holocaust survivors: Werner Reich (pictured below) and Kathy Griesz. Students gathered on Google Meets to hear their testimonies and ask questions about their experience in the Holocaust. Kathy Griesz was born and raised in Budapest, Hungary, and was 13 when Nazi Germany invaded. Along with the rest of the Jewish population of Budapest, she and her family were stripped of their property, money, and belongings (which would never be recovered), and forced into the Budapest Ghetto. In the ghetto, she was subjected to the Nazi’s dehumanization campaign against the Jews and the everpresent fear of being killed for her family’s religious beliefs. Due to the (relative) late occupation of Hungary by the Nazis, Kathy and her immediate family were spared the horrors of the concentration camps, but much of her extended family were not. Werner Reich was 15 and living in Yugoslavia when he was arrested by the Gestapo after being found hiding with resistance soldiers. Over the next two years, he was transported to multiple concentration camps, before ultimately ending up in Auschwitz. -

Jewish Historical Museum Archival Material Guide

JEWISH HISTORICAL MUSEUM ARCHIVAL MATERIAL GUIDE BELGRADE 2020. Archival material of the Jewish Historical Museum FJCS 1. Jewish Church - School Community of Belgrade („Moscow material“ and „Lvovska material“) - over 100.000 records, from 1876. until 1941. 2. Federation of Jewish Communities of Yugoslavia - 4 boxes (AJHM,FJCY) 3. Jewish Municipality of Belgrade - 4 boxes (AJHM,JMB) 4. Jewish Municipality of Zemun - 3 boxes (AJHM,JMZm) 5. Jewish Municipality of Stari Becej - 2 boxes (AJHM,JMSB) 6. Jewish Municipality of Sarajevo and region of BiH (Bosnia and Hercegovina) - 2 boxes (AJHM,JMS) 7. Jewish Municipality of Rijeka, Opatija and Maribor - 1 box (AJHM,JMROM) 8. Jewish Municipality of Macedonian region - 2 boxes (AJHM,Mc) 9. Jewish Municipality of Krizevci - 5 boxes (AJHM,JMKz) 10. Jewish Municipality of Zagreb - 12 boxes (AJHM,JMZ) 11. Jewish Municipality of Novi Sad, Subotica and region of Vojvodina - 3 boxes (AJHM,JMNS-S) 12. Cultural activity of Jews in Yugoslavia - 10 boxes (AJHM,CAJ) pg. 1 1. Jewish social organizations – women's societies, humanitarian societies, Jewish schools, Jewish kindergartens, sports societies (AJHM,JSO) 2. Synagogues - 3 boxes (AJHM,Synagogues) 3. Monuments for Victims of Fascizm - 2 boxes (AJHM,MVF) 4. Jewish Cemeteries - 2 boxes (AJHM,JC) 5. Commemorations - 1 box (AJHM,Commemorations) 6. Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade - 1 box (AJHM,JHM) 7. Jewish Museums in the World - 3 boxes (AJHM,JMW) 8. General material-Croatia - 1 box (AJHM,Croatia) 9. Jews in the Balkan Wars and the World War I - 1 box (AJHM,BFWW) 10. Jews in the Spanish Civil War - 1 kutija (AJHM,SCW) 11.