The Holocaust in Hungary – a Child’S Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizensâ•Ž Motives Near

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Tenth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2019 From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the European History Commons, and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons Green, Jordan, "From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust" (2019). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2019/holocaust/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green History 395 James Madison University Spring 2018 Dr. Michael J. Galgano The Holocaust has raised difficult questions since its end in April 1945 including how could such an atrocity happen and how could ordinary people carry out a policy of extermination against a whole race? To answer these puzzling questions, most historians look inside the Nazi Party to discern the Holocaust’s inner-workings: official decrees and memos against the Jews and other untermenschen1, the role of the SS, and the organization and brutality within concentration and extermination camps. However, a vital question about the Holocaust is missing when examining these criteria: who was watching? Through research, the local inhabitants’ knowledge of a nearby concentration camp, extermination camp or mass shooting site and its purpose was evident and widespread. -

The Holocaust in Hungary

THE HOLOCAUST IN HUNGARY When the Germans entered Hungary on March 19, 1944, its more than 800,000 Jews were the last intact Jewish community in occupied Europe. Between May 14 and July 9 – in less than two months and on the very eve of Allied victory – more than 400,000 were deported to Auschwitz, where 75% were killed immediately. Such swift, concentrated destruction could not have happened without the help of local collaborators – help Adolf Eichmann clearly expected when he brought only 200 staff with him to oversee the deportations. Collaborators included the government, the right wing parties, and the law-enforcement agencies, bolstered by the tacit approval of most non-Jews and Church authorities. Indeed, laws allowing synagogues to be expropriated for secular use and the many private requests for real estate and other property formerly owned by Jews, indicate that few expected any Jews to return. The Vatican, the International Red Cross, the Allies, and the neutral powers also had a role in the catastrophe, since it took place when details of the “Final Solution” – especially the Hungarian situation – were already known to them. In summer 1944, at the height of the deportations, the Allies rejected Jewish underground leaders’ pleas to bomb Auschwitz and the rail lines leading to it, claiming that bombers flying from Britain were incapable of attacking Poland and could not be diverted to targets not "military related." To be sure, pressure from President Roosevelt, Sweden’s king, and the pope – combined with the success of Operation Overlord and the Soviet Union’s summer offensive and Allied intimations they would carpet-bomb Budapest if its Jews were deported – did force Regent Miklos Horthy to stop the trains on July 7, 1944. -

Holocaust/Shoah the Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-Day Poland

NOW AVAILABLE remembrance a n d s o l i d a r i t y Holocaust/Shoah The Organization of the Jewish Refugees in Italy Holocaust Commemoration in Present-day Poland in 20 th century european history Ways of Survival as Revealed in the Files EUROPEAN REMEMBRANCE of the Ghetto Courts and Police in Lithuania – LECTURES, DISCUSSIONS, remembrance COMMENTARIES, 2012–16 and solidarity in 20 th This publication features the century most significant texts from the european annual European Remembrance history Symposium (2012–16) – one of the main events organized by the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity in Gdańsk, Berlin, Prague, Vienna and Budapest. The 2017 issue symposium entitled ‘Violence in number the 20th-century European history: educating, commemorating, 5 – december documenting’ will take place in Brussels. Lectures presented there will be included in the next Studies issue. 2016 Read Remembrance and Solidarity Studies online: enrs.eu/studies number 5 www.enrs.eu ISSUE NUMBER 5 DECEMBER 2016 REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY EDITED BY Dan Michman and Matthias Weber EDITORIAL BOARD ISSUE EDITORS: Prof. Dan Michman Prof. Matthias Weber EDITORS: Dr Florin Abraham, Romania Dr Árpád Hornják, Hungary Dr Pavol Jakubčin, Slovakia Prof. Padraic Kenney, USA Dr Réka Földváryné Kiss, Hungary Dr Ondrej Krajňák, Slovakia Prof. Róbert Letz, Slovakia Prof. Jan Rydel, Poland Prof. Martin Schulze Wessel, Germany EDITORIAL COORDINATOR: Ewelina Pękała REMEMBRANCE AND SOLIDARITY STUDIES IN 20TH CENTURY EUROPEAN HISTORY PUBLISHER: European Network Remembrance and Solidarity ul. Wiejska 17/3, 00–480 Warszawa, Poland www.enrs.eu, [email protected] COPY-EDITING AND PROOFREADING: Caroline Brooke Johnson PROOFREADING: Ramon Shindler TYPESETTING: Marcin Kiedio GRAPHIC DESIGN: Katarzyna Erbel COVER DESIGN: © European Network Remembrance and Solidarity 2016 All rights reserved ISSN: 2084–3518 Circulation: 500 copies Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag. -

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

World War II, Shoah and Genocide

International Conference “The Holocaust: Remembrance and Lessons” 4 - 5 July 2006, Riga, Latvia Evening lecture at the Big Hall of Latvian University The Holocaust in its European Context Yehuda Bauer Allow me please, at the outset, to place the cart firmly before the horse, and set before you the justification for this paper, and in a sense, its conclusion. The Holocaust – Shoah – has to be seen in its various contexts. One context is that of Jewish history and civilisation, another is that of antisemitism, another is that of European and world history and civilisation. There are two other contexts, and they are very important: the context of World War II, and the context of genocide, and they are connected. Obviously, without the war, it is unlikely that there would have been a genocide of the Jews, and the war developments were decisive in the unfolding of the tragedy. Conversely, it is increasingly recognized today that while one has to understand the military, political, economic, and social elements as they developed during the period, the hard core, so to speak, of the World War, its centre in the sense of its overall cultural and civilisational impact, were the Nazi crimes, and first and foremost the genocide of the Jews which we call the Holocaust, or Shoah. The other context that I am discussing here is that of genocide – again, obviously, the Holocaust was a form of genocide. If so, the relationship between the Holocaust and other genocides or forms of genocide are crucial to the understanding of that particular tragedy, and of its specific and universal aspects. -

Holocaust Memorial Days an Overview of Remembrance and Education in the OSCE Region

Holocaust Memorial Days An overview of remembrance and education in the OSCE region 27 January 2015 Updated October 2015 Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 Albania ................................................................................................................................. 13 Andorra ................................................................................................................................. 14 Armenia ................................................................................................................................ 16 Austria .................................................................................................................................. 17 Azerbaijan ............................................................................................................................ 19 Belarus .................................................................................................................................. 21 Belgium ................................................................................................................................ 23 Bosnia and Herzegovina ....................................................................................................... 25 Bulgaria ............................................................................................................................... -

Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2001 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, March 2004 Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi Laszlo Berkowits, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Tim Cole, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by István Deák, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Eva Hevesi Ehrlich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Charles Fenyvesi; Copyright © 2001 by Paul Hanebrink, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Albert Lichtmann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by George S. Pick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum In Charles Fenyvesi's contribution “The World that Was Lost,” four stanzas from Czeslaw Milosz's poem “Dedication” are reprinted with the permission of the author. Contents -

Hungary at Crossroads: War, Peace, and Occupation Politics (1918-1946)

HUNGARY AT CROSSROADS: WAR, PEACE, AND OCCUPATION POLITICS (1918-1946) The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by IŞIL TİPİOĞLU In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA July 2019 ABSTRACT HUNGARY AT CROSSROADS: WAR, PEACE, AND OCCUPATION POLITICS (1918-1946) Tipioğlu, Işıl M.A., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Hakan Kırımlı July, 2019 This thesis traces the steps of the Hungarian foreign policy from 1918 to 1946, and analyzes the impact of revisionism after the Treaty of Trianon on Hungarian foreign policy decisions and calculations after the First World War. Placing the Hungarian revisionism at its center, this thesis shows the different situation Hungary had as a South European power as an ally of Germany throughout the Second World War and subsequently under the Soviet occupation. It also argues that it was the interlinked Hungarian foreign policy steps well before 1941, the official Hungarian participation in the war, which made Hungary a belligerent country. Also, based largely on the American archival documents, this study places Hungary into a retrospective framework of the immediate post-war era in Europe, where the strong adherence to Nazi Germany and the Hungarian revisionism shaped the future of the country. Key Words: European Politics, Hungary, Revisionism, the Second World War, Twentieth Century iii ÖZET YOL AYRIMINDA MACARİSTAN: SAVAŞ, BARIŞ VE İŞGAL POLİTİKALARI (1918-1946) Tipioğlu, Işıl Yüksek Lisans, Uluslararası İlişkiler Bölümü Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. Hakan Kırımlı Temmuz, 2019 Bu tez, 1918’den 1946’ya kadar olan Macar dış politikası adımlarını takip ederek Trianon Antlaşması’ndan sonra ortaya çıkan Macar revizyonizminin, Macar dış politika kararlarında ve hesaplamalarındaki etkisini analiz etmektedir. -

Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe Symposium Presentations W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe Symposium Presentations CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2004 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2004 Copyright © 2004 by Peter Hayes, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Michael Thad Allen, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Paul Jaskot, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Wolf Gruner, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Christopher R. Browning, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by William Rosenzweig, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Andrej Angrick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Sarah B. Farmer, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Rolf Keller, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................i -

Hungary: the Assault on the Historical Memory of The

HUNGARY: THE ASSAULT ON THE HISTORICAL MEMORY OF THE HOLOCAUST Randolph L. Braham Memoria est thesaurus omnium rerum et custos (Memory is the treasury and guardian of all things) Cicero THE LAUNCHING OF THE CAMPAIGN The Communist Era As in many other countries in Nazi-dominated Europe, in Hungary, the assault on the historical integrity of the Holocaust began before the war had come to an end. While many thousands of Hungarian Jews still were lingering in concentration camps, those Jews liberated by the Red Army, including those of Budapest, soon were warned not to seek any advantages as a consequence of their suffering. This time the campaign was launched from the left. The Communists and their allies, who also had been persecuted by the Nazis, were engaged in a political struggle for the acquisition of state power. To acquire the support of those Christian masses who remained intoxicated with anti-Semitism, and with many of those in possession of stolen and/or “legally” allocated Jewish-owned property, leftist leaders were among the first to 1 use the method of “generalization” in their attack on the facticity and specificity of the Holocaust. Claiming that the events that had befallen the Jews were part and parcel of the catastrophe that had engulfed most Europeans during the Second World War, they called upon the survivors to give up any particularist claims and participate instead in the building of a new “egalitarian” society. As early as late March 1945, József Darvas, the noted populist writer and leader of the National Peasant -

We Were There. a Collection of Firsthand Testimonies

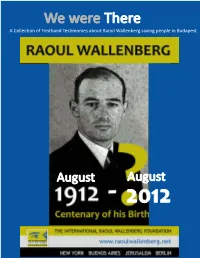

We were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies about Raoul Wallenberg saving people in Budapest August August 2012 We Were There A Collection of Firsthand Testimonies About Raoul Wallenberg Saving People in Budapest 1 Contributors Editors Andrea Cukier, Daniela Bajar and Denise Carlin Proofreader Benjamin Bloch Graphic Design Helena Muller ©2012. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) Copyright disclaimer: Copyright for the individual testimonies belongs exclusively to each individual writer. The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) claims no copyright to any of the individual works presented in this E-Book. Acknowledgments We would like to thank all the people who submitted their work for consideration for inclusion in this book. A special thanks to Denise Carlin and Benjamin Bloch for their hard work with proofreading, editing and fact-checking. 2 Index Introduction_____________________________________4 Testimonies Judit Brody______________________________________6 Steven Erdos____________________________________10 George Farkas___________________________________11 Erwin Forrester__________________________________12 Paula and Erno Friedman__________________________14 Ivan Z. Gabor____________________________________15 Eliezer Grinwald_________________________________18 Tomas Kertesz___________________________________19 Erwin Koranyi____________________________________20 Ladislao Ladanyi__________________________________22 Lucia Laragione__________________________________24 Julio Milko______________________________________27 -

The Holocaust in Hungary Fifty Years Later' and Eby, 'Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II'

Habsburg Dreisziger on Braham and Pok, 'The Holocaust in Hungary Fifty Years Later' and Eby, 'Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II' Review published on Thursday, October 1, 1998 Randolph L. Braham, Attila Pok, eds. The Holocaust in Hungary Fifty Years Later. New York and Budapest: Columbia University Press, 1987. 783 pp. $112.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-88033-374-0.Cecil D. Eby. Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998. xx + 318 pp. $35.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-271-01739-6. Reviewed by Nandor F. Dreisziger (Royal Military College of Canada)Published on HABSBURG (October, 1998) Jews and Gentiles, Soldiers and Civilians: Hungary during World War II The Holocaust arrived rather late to wartime Hungary. Until its occupation by theWehrmacht in March 1944, Hungary was a haven for Hungarian Jews, the existence of anti-Jewish legislation and the maltreatment of Jewish conscripts in some labour battalions notwithstanding. Jewish refugees to Hungary from the East, and Jews in certain war-zones occupied by the Hungarian army, were not safe. And when the Holocaust arrived, it came with a vengeance. As is well-known, the deportation of Jews from the Hungarian countryside took place in a very short time--in less than two months. One reason for this, according to more than one author in Braham's volume, was the high degree of cooperation on the part of Hungary's security organs with Eichmann's special force in charge of the operation. But other factors played roles as well.