Introduction to Contemporary Social Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

ASA Theory Section Debate on Theoretical Work, Pluralism, and Sociological Theory Below are the original essay by Stephen Sanderson in Perspectives, the Newsletter of the ASA Theory section (August 2005), and the responses it received from Julia Adams, Andrew Perrin, Dustin Kidd, and Christopher Wilkes (February 2006). Also included is a lengthier version of Sanderson’s reply than the one published in the print edition of the newsletter. REFORMING THEORETICAL WORK IN SOCIOLOGY: A MODEST PROPOSAL Stephen K. Sanderson Indiana University of Pennsylvania Thirty-five years ago, Alvin Gouldner (1970) predicted a coming crisis of Western sociology. Not only did he turn out to be right, but if anything he underestimated the severity of the crisis. This crisis has been particularly severe in the subfield of sociology generally known as “theory.” At least that is my view, as well as that of many other sociologists who are either theorists or who pay close attention to theory. Along with many of the most trenchant critics of contemporary theory (e.g., Jonathan Turner), I take the view that sociology in general, and sociological theory in particular, should be thoroughly scientific in outlook. Working from this perspective, I would list the following as the major dimensions of the crisis currently afflicting theory (cf. Chafetz, 1993). 1. An excessive concern with the classical theorists. Despite Jeffrey Alexander’s (1987) strong argument for “the centrality of the classics,” mature sciences do not show the kind of continual concern with the “founding fathers” that we find in sociological theory. It is all well and good to have a sense of our history, but in the mature sciences that is all it amounts to – history. -

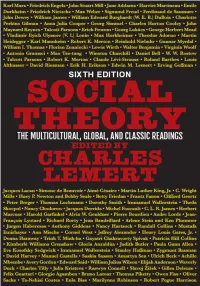

SOCIAL THEORY: the Multicultural, Global, and Classic Readings

SOCIAL THEORY SIXTH EDITION SOCIAL THEORY The Multicultural, Global, and Classic Readings EDITED WITH COMMENTARIES BY CHARLES LEMERT New York London First published 2017 by Westview Press Published 2018 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © 2017 by Charles Lemert All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Every effort has been made to secure required permissions for all text, images, maps, and other art reprinted in this volume. Names: Lemert, Charles C., 1937- author. Title: Social theory : the multicultural, global, and classic readings / Charles Lemert. Description: Sixth Edition. | Boulder : Westview Press, 2016. | Revised edition of Social theory, 2013. Identifiers: LCCN 2016015315 (print) | LCCN 2016016941 (ebook) | ISBN 9780813350028 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780813350448 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Sociology. | Sociology--History. Classification: LCC HM585 .L3936 2016 (print) | LCC HM585 (ebook) | DDC 301--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016015315 -

2003 Annual Meeting Program: New Orleans, LA

FINAL THE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN GEOGRAPHERS Photo courtesy of New Orleans Convention & Visitors Bureau 99th Annual Meeting 5 - 8 March 2003 New Orleans, LA Advancing Geography in Partnership With You PROGRAM 1 INSERT WH FREEMAN AD 2 THE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICAN GEOGRAPHERS 99th Annual Meeting 5 - 8 March 2003 New Orleans, LA PROGRAM The Association of American Geographers 1710 16th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009-3198 Phone (202) 234-1450 Fax (202) 234-2744 Web www.aag.org E-mail [email protected] 3 INSERT ISLAND PRESS AD 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2003 Annual Meeting Committees ........................................ 6 AAG Officers, Councillors and Staff ..................................... 7 General Information ..............................................................12 2004 Annual Meeting Information ....................................... 15 Special Events ...................................................................... 18 World Geography Bowl........................................................24 Specialty Group Business Meetings .................................... 28 Workshops ..........................................................................31 Field Trips ............................................................................ 36 Exhibit Hall Floor Plan .......................................................... 45 Exhibitors ............................................................................. 46 Advertisers ..........................................................................48 Conference At A Glance -

The New Individualism

The New Individualism Corporate networking, compulsive consumerism, plastic surgery, therapeutic tribulations, instant identity makeovers and reality TV: welcome to life in our increasingly individualized world. In this dazzling book, Anthony Elliott and Charles Lemert explore the cul- ture of the ‘new individualism’ generated by global capitalism, and develop a major new perspective on people’s emotional experiences of globalization. The New Individualism offers fascinating, but disturbing, accounts of people struggling to cope with a new individualism reshaping the world today. There is Larry, a high-tech executive ‘emotionally wrecked by success’; there is Ruth, a married woman in her late fifties, typing real-time erotica in cyberspace; there is Norman, a recovering drug addict infected with HIV, reinventing himself by accepting the deadly worlds for what they are; and Caoimhe and Annie, two little girls only beginning to explore the disorientating effects of the new individualism. This book powerfully cuts against the grain of current ortho- doxies that view globalization as corrosive of private life. Elliott and Lemert argue that today’s worlds are not only risky but deadly. Yet there is hope, the authors contend, beyond the complexities. Anthony Elliott is Professor and Chair of Sociology at Flinders University, Australia and Visiting Research Professor at the Open University, UK. His recent books, all published by Routledge, include Contemporary Social Theory: An Introduction (2009), The Routledge Companion to Social Theory (2010) and Globalization (2010). Charles Lemert is John C. Andrus Professor of Sociology at Wesleyan University, USA. His recent books include Thinking the Unthinkable (2007), Social Theory (4th edition, 2009) and Globaliza- tion (2010). -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Vani S. Kulkarni Department of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania, 3718 Locust Walk, McNeil 113, Philadelphia, PA 19104. USA. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Telephone Number: 215.515.3534 ACADEMIC POSITIONS ONGOING University of Pennsylvania: Lecturer on Sociology, Department of Sociology; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, 19104. Yale University: Senior Fellow, Urban Ethnography Project; Sociology Department; New Haven, Connecticut, United States, 06511. RECENT Yale University: Post-Doctoral Associate, Department of Sociology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 06511. 2011-2014. Yale University: Singh Fellow, Lecturer and Fellow, Department of Sociology and South Asian Studies, MacMillan Center, 2009-2011. Harvard University: Lecturer, Sociology Department, 2008-2009 David Bell Fellow, and Instructor, Harvard School of Public Health, 2006-2008. United Nations: Consultant, International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). Via Paolo di Dono, 44, 00142 Rome, Italy and Asian Development Bank (ABD), Manila, Philippines. 2009-2016. EDUCATION Degrees: Ph.D. Sociology (with Distinction), University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States Dissertation: Health, Culture & Democracy: The Case of Decentralization of Healthcare in India 1 M.Phil. Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, India M.A. Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, India B.A. (Honors) Sociology, Miranda House, University of Delhi, India Additional Diploma: Subject: SAS Programming -

The Affective Turn the Affective Turn

SOCIOLOGY/SOCIAL THEORY WITH A FOREWORD BY MICHAEL HARDT In the mid-1990s, scholars turned their attention toward the ways that ongoing political, PATRICIA economic, and cultural transformations were changing the realm of the social, specifically that aspect of it described by the notion of affect: pre-individual bodily forces, linked to autonomic TICINETO responses, which augment or diminish a body’s capacity to act or engage with others. This CLOUGH, “affective turn” and the new configurations of bodies, technology, and matter that it reveals, is the subject of this collection of essays. Scholars based in sociology, cultural studies, science editor studies, and women’s studies illuminate the movement in thought from a psychoanalytically informed criticism of subject identity, representation, and trauma to an engagement with information and affect; from a privileging of the organic body to an exploration of nonorganic Turn Affective The life; and from the presumption of equilibrium-seeking closed systems to an engagement with the complexity of open systems under far-from-equilibrium conditions. Taken together, these essays suggest that attending to the affective turn is necessary to theorizing the social. “From the trauma of cultural displacement to the political economy of affective labor, the essays brought together here examine the many facets of affect, focusing on its consequences for theories of the social and well-informed by recent rethinkings of power. Expertly framed by Patricia Clough’s introduction, the volume presents a -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REINHOLD NIEBUHR

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: REINHOLD NIEBUHR AND AN ETHIC OF POLITICAL HUMILITY IN DELIBERATIVE POLITICS Matthew Peter Spino, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Dissertation directed by: Professor James Glass Department of Government and Politics The purpose of this dissertation is to investigate the degree to which the political psychology of Reinhold Niebuhr contributes to a more capacious theory of deliberative politics and to what degree such a theory may permit individuals to express themselves with more workable forms of democratic practice. Considerations of Reinhold Niebuhr's understanding of impermanence, anxiety, self-reflection, and empathy borne of humility guide the framework of the argument in that they inform and augment individual political preferences. The author uses these ideas to develop a theory of deliberative politics built upon the empathetic tendencies found in the self-scrutinizing humility of Reinhold Niebuhr's politics. The author considers this theory in contradistinction to ascendant strains in political theory and theologies of public life, which at times may disavowal Niebuhr's understanding of natural theology, his correspondent political realism, or otherwise miscategorize Niebuhr's political claims. The degree to which Niebuhr's ethical framework can or should be separated from Christian considerations of ethics more broadly, especially from Christian eschatology, is a major topic of discussion. Contrasting Niebuhr with other Christian ethicists permits us to see in what manner Niebuhr's political psychology might retain political value beyond a particular religious community. This work also considers limits of Niebuhr's understanding of liberal politics, and whether an ethic of humility can be overly disempowering at times. Tension between individual and aggregate political perspectives frames that discussion. -

Reinhold Niebuhr's Ethics of Rhetoric Joseph E

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Reinhold Niebuhr's ethics of rhetoric Joseph E. Rhodes Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Rhodes, Joseph E., "Reinhold Niebuhr's ethics of rhetoric" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2951. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2951 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REINHOLD NIEBUHR’S ETHICS OF RHETORIC A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Joseph E. Rhodes B.A., University of Alabama, 2006 M.A., Eastern Michigan University, 2008 May 2012 Acknowledgements This dissertation is the product of many, many supportive individuals who invested their priceless resources—whether financial, emotional or temporal—into my project of Becoming. It is true what they say, that the better part of one’s life consists of his friendships, and perhaps the most important of these friendships began four years ago, when I arrived at Louisiana State University. I will be eternally grateful for Dr. Nathan Crick’s guidance and care. The compliments and gratitude Nathan receives from his students are extensive. -

EDF 703 Sociological Foundations of Education

The mission of The College of Education at Northern Arizona University isis toto prepare education professionals toto create thethe schools of tomorrow.tomorrow. EDF 703: SOCIOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF EDUCATION 3 credits Dr. Frances Julia Riemer office: COE room 162 Telephone: 928/523-0352 e-mail: [email protected] Fax: 928/523-1929 Office hours: Monday 12:00 –3:00 Course Prerequisites EDF 677 or instructor permission Course Description The purpose of this course is to provide a context in which students can examine social theory and its relationship to the analysis of educational institutions in the United States and around the world. The course deals with both the macrosociological and microsociological. Within a seminar framework, the class will read the writings of a range of social theorists and investigate ways in which theoretical perspectives have been and can be applied to the study of educational processes. Education and social structure, functional, conflict, interpretive, and critical theories of education, as well as post- modernism, feminist theory, and cultural politics will all be addressed Social theory is what we do when we find ourselves able to put into words what nobody seems to want to talk about. When we find those words, and say them, we begin to survive. For some, learning to survive leads to uncommon and exhilarating pleasures. For others, perhaps the greater number of us, it leads at least to the common pleasure - a pleasure rubbed raw with what is: the simple but necessary power of knowing that one knows what is there because one can say it. -

The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social

SOCIOLOGY/SOCIAL THEORY WITH A FOREWORD BY MICHAEL HARDT In the mid-1990s, scholars turned their attention toward the ways that ongoing political, PATRICIA economic, and cultural transformations were changing the realm of the social, specifically that aspect of it described by the notion of affect: pre-individual bodily forces, linked to autonomic TICINETO responses, which augment or diminish a body’s capacity to act or engage with others. This CLOUGH, “affective turn” and the new configurations of bodies, technology, and matter that it reveals, is the subject of this collection of essays. Scholars based in sociology, cultural studies, science editor studies, and women’s studies illuminate the movement in thought from a psychoanalytically informed criticism of subject identity, representation, and trauma to an engagement with information and affect; from a privileging of the organic body to an exploration of nonorganic Turn Affective The life; and from the presumption of equilibrium-seeking closed systems to an engagement with the complexity of open systems under far-from-equilibrium conditions. Taken together, these essays suggest that attending to the affective turn is necessary to theorizing the social. “From the trauma of cultural displacement to the political economy of affective labor, the essays brought together here examine the many facets of affect, focusing on its consequences for theories of the social and well-informed by recent rethinkings of power. Expertly framed by Patricia Clough’s introduction, the volume presents a