Joseph Plunkett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

THE ROLE OF THE GAELIC LEAGUE THOMAS MacDONAGH PATRICK PEARSE EOIN MacNEILL A League of extraordinary gentlemen Gaelic League was breeding ground for rebels, writes Richard McElligott EFLECTING on The Gaelic League was The Gaelic League quickly the rebellion that undoubtedly the formative turned into a powerful mass had given him nationalist organisation in the movement. By revitalising the his first taste of development of the revolutionary Irish language, the League military action, elite of 1916. also began to inspire a deep R Michael Collins With the rapid decline of sense of pride in Irish culture, lamented that the Easter Rising native Irish speakers in the heritage and identity. Its wide was hardly the “appropriate aftermath of the Famine, many and energetic programme of time for memoranda couched sensed the damage would be meetings, dances and festivals in poetic phrases, or actions irreversible unless it was halted injected a new life and colour DOUGLAS HYDE worked out in similar fashion”. immediately. In November 1892, into the often depressing This assessment encapsulates the Gaelic scholar Douglas Hyde monotony of provincial Ireland. the generational gulf between delivered a speech entitled ‘The Another significant factor participation in Gaelic games. cursed their memory”. Pearse the romantic idealism of the Necessity for de-Anglicising for its popularity was its Within 15 years the League had was prominent in the League’s revolutionaries of 1916 and the Ireland’. Hyde pleaded with his cross-gender appeal. The 671 registered branches. successful campaign to get Irish military efficiency of those who fellow countrymen to turn away League actively encouraged Hyde had insisted that the included as a compulsory subject would successfully lead the Irish from the encroaching dominance female participation and one Gaelic League should be strictly in the national school system. -

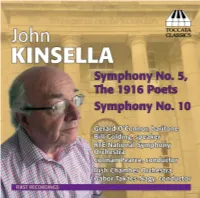

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, Delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29Th September, 2016

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29th September, 2016 As Ireland commemorates the centenary of the Easter Rising — the event that sparked a popular movement towards independence from the United Kingdom one hundred years ago this year — the tendency has been to focus, perhaps somewhat simplistically, on the history of the participants and of the event itself. But in the Easter Rising we find that history was born in literature, and reality in text. With the Celtic Revival in its latter days by 1916, and the rediscovery of national heroes from ancient myth, such as Cuchulain, permeating the popular imagination, it should not seem too surprising that a headmaster, a university professor, and an assortment of poets saw themselves — and became — the champions of Irish freedom. As the historian Standish O’Grady prophetically declared in the late nineteenth century: ‘We have now a literary movement, it is not very important; it will be followed by a political movement that will not be very important; then must come a military movement that will be important indeed.’1 The ideas crafted in the study took fire in the streets in 1916, and Joseph Mary Plunkett — poet, aesthete, military strategist, and rebel — offers a fascinating study of this nexus of thought and action. Plunkett is often mythologized as the hero who wed his sweetheart on the eve of his execution in May 1916, but I would like to broaden this narrative by framing this evening’s talk around not one but three women who profoundly shaped Plunkett’s life, and who are the subject of many poems he wrote, some of which I would like to share with you this evening. -

Joseph Mary Plunkett - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Joseph Mary Plunkett - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joseph Mary Plunkett(21 November 1887 – 4 May 1916) Joseph Mary Plunkett (Irish: Seosamh Máire Pluincéid) was an Irish nationalist, poet, journalist, and a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. <b>Background</b> Plunkett was born at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street in one of Dublin's most affluent neighborhoods. Both his parents came from wealthy backgrounds, and his father, George Noble Plunkett, had been made a papal count. Despite being born into a life of privilege, young Joe Plunkett did not have an easy childhood. Plunkett contracted tuberculosis at a young age. This was to be a lifelong burden. His mother was unwilling to believe his health was as bad as it was. He spent part of his youth in the warmer climates of the Mediterranean and north Africa. He was educated at the Catholic University School (CUS) and by the Jesuits at Belvedere College in Dublin and later at Stonyhurst College, in Lancashire, where he acquired some military knowledge from the Officers' Training Corps. Throughout his life, Joseph Plunkett took an active interest in Irish heritage and the Irish language, and also studied Esperanto. Plunkett was one of the founders of the Irish Esperanto League. He joined the Gaelic League and began studying with Thomas MacDonagh, with whom he formed a lifelong friendship. The two were both poets with an interest in theater, and both were early members of the Irish Volunteers, joining their provisional committee. Plunkett's interest in Irish nationalism spread throughout his family, notably to his younger brothers George and John, as well as his father, who allowed his property in Kimmage, south Dublin, to be used as a training camp for young men who wished to escape conscription in England during World War I. -

Irish Working-Class Poetry 1900-1960

Irish Working-Class Poetry 1900-1960 In 1936, writing in the Oxford Book of Modern Verse, W.B. Yeats felt the need to stake a claim for the distance of art from popular political concerns; poets’ loyalty was to their art and not to the common man: Occasionally at some evening party some young woman asked a poet what he thought of strikes, or declared that to paint pictures or write poetry at such a moment was to resemble the fiddler Nero [...] We poets continued to write verse and read it out at the ‘Cheshire Cheese’, convinced that to take part in such movements would be only less disgraceful than to write for the newspapers.1 Yeats was, of course, striking a controversial pose here. Despite his famously refusing to sign a public letter of support for Carl von Ossietzky on similar apolitical grounds, Yeats was a decidedly political poet, as his flirtation with the Blueshirt movement will attest.2 The political engagement mocked by Yeats is present in the Irish working-class writers who produced a range of poetry from the popular ballads of the socialist left, best embodied by James Connolly, to the urban bucolic that is Patrick Kavanagh’s late canal-bank poetry. Their work, whilst varied in scope and form, was engaged with the politics of its time. In it, the nature of the term working class itself is contested. This conflicted identity politics has been a long- standing feature of Irish poetry, with a whole range of writers seeking to appropriate the voice of ‘The Plain People of Ireland’ for their own political and artistic ends.3 1 W.B. -

Coffey & Chenevix Trench

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 153 Coffey & Chenevix Trench Papers (MSS 46,290 – 46,337) (Accession No. 6669) Papers relating to the Coffey and Chenevix Trench families, 1868 – 2007. Includes correspondence, diaries, notebooks, pamphlets, leaflets, writings, personal papers, photographs, and some papers relating to the Trench family. Compiled by Avice-Claire McGovern, October 2009 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction....................................................................................................................... 4 I. Coffey Family............................................................................................................... 16 I.i. Papers of George Coffey........................................................................................... 16 I.i.1 Personal correspondence ....................................................................................... 16 I.i.1.A. Letters to Jane Coffey (née L’Estrange)....................................................... 16 I.i.1.B. Other correspondence ................................................................................... 17 I.i.2. Academia & career............................................................................................... 18 I.i.3 Politics ................................................................................................................... 22 I.i.3.A. Correspondence ........................................................................................... -

"The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title "The Given Note": traditional music and modern Irish poetry Author(s) Crosson, Seán Publication Date 2008 Publication Crosson, Seán. (2008). "The Given Note": Traditional Music Information and Modern Irish Poetry, by Seán Crosson. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Publisher Cambridge Scholars Publishing Link to publisher's http://www.cambridgescholars.com/the-given-note-25 version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6060 Downloaded 2021-09-26T13:34:31Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. "The Given Note" "The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry By Seán Crosson Cambridge Scholars Publishing "The Given Note": Traditional Music and Modern Irish Poetry, by Seán Crosson This book first published 2008 by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 15 Angerton Gardens, Newcastle, NE5 2JA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2008 by Seán Crosson All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-84718-569-X, ISBN (13): 9781847185693 Do m’Athair agus mo Mháthair TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................. -

The Tyranny of the Past?

The Tyranny of the Past? Revolution, Retrospection and Remembrance in the work of Irish writer, Eilis Dillon Volumes I & II Anne Marie Herron PhD in Humanities (English) 2011 St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra (DCU) Supervisors: Celia Keenan, Dr Mary Shine Thompson and Dr Julie Anne Stevens I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD in Humanities (English) is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: (\- . Anne Marie Herron ID No.: 58262954 Date: 4th October 2011 Thesis Abstract This thesis examines the extent to which Eilis Dillon's (1920-94) reliance on memory and her propensity to represent the past was, for her, a valuable motivating power and/or an inherited repressive influence in terms of her choices of genres, subject matter and style. Volume I of this dissertation consists of a comprehensive survey and critical analysis of Dillon's writing. It addresses the thesis question over six chapters, each of which relates to a specific aspect of the writer's background and work. In doing so, the study includes the full range of genres that Dillon employed - stories and novels in both Irish and English for children of various age-groups, teenage adventure stories, as well as crime fiction, literary and historical novels, short stories, poetry, autobiography and works of translation for an adult readership. The dissertation draws extensively on largely untapped archival material, including lecture notes, draft documents and critical reviews of Dillon's work. -

April 2016 Ianohio.Com 2 IAN Ohio “We’Ve Always Been Green!” APRIL 2016

April 2016 ianohio.com 2 IAN Ohio “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com APRIL 2016 Ancient Order of Hibernians Division Installs Triplet Sons of Charter Member The Amsden Triplets, from left: Alex, Father- Eric, David & Luke The Irish Brigade Division #1 of Medina are juniors at Midview High School in County Charter Member Eric Amsden Grafton, Ohio. brought his seventeen year old triplet sons to be installed in the division. Eric The division is always glad to see the was able to lead his sons in the pledge of sons of members join, but was especially the Order. The newest Hibernians are pleased to have this unique Alex, David and Luke Amsden. All three experience happen. West Side Irish American Club Upcoming Events: Live Music & Food in The Pub every Friday 6th – Wine Tasting 23rd – 1916 Easter Rising Centennial Celebration 24th – Annual Style Show & Luncheon General Meeting 3rd Thursday of every month. Since 1931 8559 Jennings Road Olmsted, Twp, Ohio 44138 440.235.5868 www.wsia-club.org APRIL 2016 “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com 3 One of my favorite people is and breaks we have received. To Editor’s Corner Pulitzer Prize winning author and those that paved the path, that columnist Regina Brett. She writes planted seeds or nurtured their with and of common sense, caring, growing, to those who received leaving the judgement at the door the honors and the appreciation, in a life well-lived and the lessons and those who did it without any learned. She says in her book, God recognition at all, I wish to say, Never Blinks, “People don’t want Thank you. -

Poems of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood

POEMS OF THE ISH REVOLUTIONARY BROTHERHOOD THOMAS MacDONAGH P. H. PEARSE (PADRAIG MacPIARAIS) JOSEPH MARY PLUNKETT SIR ROGER CASEMENT library university tufts Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/poemsofirishrevo00colu_0 POEMS OF THE IRISH REVOLUTIONARY BROTHERHOOD POEMS OF THE IRISH REVOLUTIONARY BROTHERHOOD THOMAS MacDONAGH P. H. PEARSE (Padraic MacPiarais) JOSEPH MARY PLUNKETT SIR ROGER CASEMENT Edited by Padraic Cplum AND Edward J. O’Brien Boston Small, Maynard & Company 1916 Copyright, 1916 By Small, Maynard & Company (Incorporated) : CONTENTS Page Introduction vii Prologue: Ways of War. By Lionel Johnson i Thomas MacDonagii: John-John 3 Song from the Irish .... 6 “ ” Envoi to Songs of Myself . 8 Of a Poet Patriot . .11 Death 12 Requies 13 Though Silence Be the Meed of Death 14 Wishes for My Son . .15 O Star of Death . .18 Padraic H. Pearse (Padraic Mac- Piarais) Ideal 24 To Death 26 The World hath Conquered . 27 CONTENTS Page The Dirge of Oliver Grace . 28 On the Fall of the Gael . .33 Joseph Mary Plunkett: White Dove of the Wild Dark Eyes . 36 The Glories of the World Sink Down in Gloom 37 When all the Stars Become a Memory 39 Poppies 40 The Dark Way 41 The Eye-Witness . .44 I See the His Blood upon Rose . 47 1847-1891 48 1867 49 The Stars Sang in God’s Garden . 50 Our Heritage 51 Sir Roger Casement: In the Streets of Catania . .52 Hamilcar Barca . -54 Epilogue: The Song of Red Hanrahan. By W . B. Yeats 56 Notes by P. H. Pearse . .58 Bibliography . .60 INTRODUCTION The years that brought maturity to the three poets who were foremost to sign, and foremost to take arms to assert, Ireland’s Declaration of Inde- pendence, may come to be looked back on as signal days in Irish history. -

Easter Rising of 1916 Chairs: Abby Nicholson ’19 and Lex Keegan Jiganti ’19 Rapporteur: Samantha Davidson ’19

Historical Crisis: Easter Rising of 1916 Chairs: Abby Nicholson ’19 and Lex Keegan Jiganti ’19 Rapporteur: Samantha Davidson ’19 CAMUN 2018: Easter Rising of 1916 Page 1 of 6 Dear Delegates, Welcome to CAMUN 2018! Our names are Abby Nicholson and Lex Keegan Jiganti and we are very excited to be chairing this committee. We are both juniors at Concord Academy and have done Model UN since our freshman year. After much debate over which topic we should discuss, we decided to run a historical crisis committee based on the Easter Rising of 1916. While not a commonly known historical event, the Easter Rising of 1916 was a significant turning point in the relations between Ireland and Great Britain. With recent issues such as Brexit and the Scottish Referendum, it is more crucial than ever to examine the effects of British imperialism and we hope that this committee will offer a lens with which to do so. The committee will start on September 5th, 1914, as this was when the Irish Republican Brotherhood first met to discuss planning an uprising before the war ended. While the outcome of the Rising is detailed in this background guide, we are intentionally beginning debate two years prior in order to encourage more creative and effective plans and solutions than what the rebels actually accomplished. This is a crisis committee, meaning that delegates will be working to pass directives and working with spontaneous events as they unfold as opposed to simply writing resolutions. We hope this background guide provides an adequate summary of the event, but we encourage further research on both the topic and each delegate’s assigned person.