A Critical Introduction to the Work of James Plunkett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Get Off Your Knees”: Mother Jones, James Connolly and Jim Larkin in the Fight for a Global Labour Movement—Rosemary Feurer

“Get off Your Knees”: Mother Jones, James Connolly and Jim Larkin in the fight for a Global Labour Movement—Rosemary Feurer The following 1910 speech excerpt by Mother Jones fits her classic style. It’s a folk harangue of the money powers and their attempt to squeeze the life out of democracy and workers, paired with a deep faith in the ability of ordinary people to counter this power: “The education of this country is a farce. Children must memorize a lot of stuff about war and murder, but are taught absolutely nothing of the economic conditions under which they must work and live. This nation is but an oligarchy….controlled by the few. You can count on your fingers the men who have this country in their absolute grasp. They can precipitate a panic; they can scare or starve us all into submission. But they will not for long, according to my notion. For, although they give us sops whenever they think we are asserting a little independence, we will not always be fooled. Some day we will have the courage to rise up and strike back at these great 'giants' of industry, and then we will see that they weren't 'giant' after all—they only seemed so because we were on our knees and they towered above us. The Labor World October 29, 1910 Cleveland Ohio If we listen carefully, we will hear more than Mother Jones’ Cork inflection as we imagine her delivering this speech. The comment about rising from the knees to strike back is well-associated with the iconic anthem of the 1913 Dublin uprising and Jim Larkin. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

Revolutionary Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War: A

Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Darlington, RR http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2012.731834 Title Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Authors Darlington, RR Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/19226/ Published Date 2012 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Re-evaluating Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War Abstract It has been argued that support for the First World War by the important French syndicalist organisation, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) has tended to obscure the fact that other national syndicalist organisations remained faithful to their professed workers’ internationalism: on this basis syndicalists beyond France, more than any other ideological persuasion within the organised trade union movement in immediate pre-war and wartime Europe, can be seen to have constituted an authentic movement of opposition to the war in their refusal to subordinate class interests to those of the state, to endorse policies of ‘defencism’ of the ‘national interest’ and to abandon the rhetoric of class conflict. This article, which attempts to contribute to a much neglected comparative historiography of the international syndicalist movement, re-evaluates the syndicalist response across a broad geographical field of canvas (embracing France, Italy, Spain, Ireland, Britain and America) to reveal a rather more nuanced, ambiguous and uneven picture. -

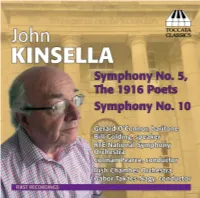

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, Delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29Th September, 2016

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29th September, 2016 As Ireland commemorates the centenary of the Easter Rising — the event that sparked a popular movement towards independence from the United Kingdom one hundred years ago this year — the tendency has been to focus, perhaps somewhat simplistically, on the history of the participants and of the event itself. But in the Easter Rising we find that history was born in literature, and reality in text. With the Celtic Revival in its latter days by 1916, and the rediscovery of national heroes from ancient myth, such as Cuchulain, permeating the popular imagination, it should not seem too surprising that a headmaster, a university professor, and an assortment of poets saw themselves — and became — the champions of Irish freedom. As the historian Standish O’Grady prophetically declared in the late nineteenth century: ‘We have now a literary movement, it is not very important; it will be followed by a political movement that will not be very important; then must come a military movement that will be important indeed.’1 The ideas crafted in the study took fire in the streets in 1916, and Joseph Mary Plunkett — poet, aesthete, military strategist, and rebel — offers a fascinating study of this nexus of thought and action. Plunkett is often mythologized as the hero who wed his sweetheart on the eve of his execution in May 1916, but I would like to broaden this narrative by framing this evening’s talk around not one but three women who profoundly shaped Plunkett’s life, and who are the subject of many poems he wrote, some of which I would like to share with you this evening. -

Writing the History of Women's Programming at Telifís Éireann: A

Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media no. 20, 2020, pp. 38–53 DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.20.04 Writing the History of Women’s Programming at Telifís Éireann: A Case Study of Home for Tea Morgan Wait Abstract: The history of women’s programming at the Irish television station Teilifís Éireann has long been neglected within the historiography of Irish television. Seminal studies within the field have focused quite specifically on the institutional history of the Irish station and have not paid much attention to programming. This is particularly true in regard to women’s programmes. This paper addresses this gap in the literature by demonstrating a methodological approach for reconstructing this lost segment of programming using the example of Home for Tea, a women’s magazine programme that ran on TÉ from 1964 to 1966. It was the network’s flagship women’s programme during this period but is completely absent from within the scholarship on Irish television. Drawing on the international literature on the history of women’s programmes this paper utilises press sources to reconstruct the Home for Tea’s content and discourse around it. It argues that, though Home for Tea has been neglected, a reconstruction of the programme illuminates wider themes of the everyday at Teilifís Éireann, such as a middle-class bias and the treatment of its actors. As such, its reconstruction, and that of other similar programmes, are exceptionally important in moving towards a more holistic history of the Irish station. In 1964, a woman from Rush wrote to the RTV Guide with a complaint about Irish national broadcaster Telifís Éireann’s schedule. -

Joseph Mary Plunkett - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Joseph Mary Plunkett - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joseph Mary Plunkett(21 November 1887 – 4 May 1916) Joseph Mary Plunkett (Irish: Seosamh Máire Pluincéid) was an Irish nationalist, poet, journalist, and a leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. <b>Background</b> Plunkett was born at 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street in one of Dublin's most affluent neighborhoods. Both his parents came from wealthy backgrounds, and his father, George Noble Plunkett, had been made a papal count. Despite being born into a life of privilege, young Joe Plunkett did not have an easy childhood. Plunkett contracted tuberculosis at a young age. This was to be a lifelong burden. His mother was unwilling to believe his health was as bad as it was. He spent part of his youth in the warmer climates of the Mediterranean and north Africa. He was educated at the Catholic University School (CUS) and by the Jesuits at Belvedere College in Dublin and later at Stonyhurst College, in Lancashire, where he acquired some military knowledge from the Officers' Training Corps. Throughout his life, Joseph Plunkett took an active interest in Irish heritage and the Irish language, and also studied Esperanto. Plunkett was one of the founders of the Irish Esperanto League. He joined the Gaelic League and began studying with Thomas MacDonagh, with whom he formed a lifelong friendship. The two were both poets with an interest in theater, and both were early members of the Irish Volunteers, joining their provisional committee. Plunkett's interest in Irish nationalism spread throughout his family, notably to his younger brothers George and John, as well as his father, who allowed his property in Kimmage, south Dublin, to be used as a training camp for young men who wished to escape conscription in England during World War I. -

The Struggle for a Left Praxis in Northern Ireland

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2011 Sandino Socialists, Flagwaving Comrades, Red Rabblerousers: The trS uggle for a Left rP axis in Northern Ireland Benny Witkovsky SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Witkovsky, Benny, "Sandino Socialists, Flagwaving Comrades, Red Rabblerousers: The trS uggle for a Left rP axis in Northern Ireland" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1095. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1095 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Witkovsky 1 SANDINO SOCIALISTS, FLAGWAVING COMRADES, RED RABBLEROUSERS: THE STRUGGLE FOR A LEFT PRAXIS IN NORTHERN IRELAND By Benny Witkovsky SIT: Transformation of Social and Political Conflict Academic Director: Aeveen Kerrisk Project Advisor: Bill Rolston, University of Ulster School of Sociology and Applied Social Studies, Transitional Justice Institute Spring 2011 Witkovsky 2 ABSTRACT This paper is the outcome of three weeks of research on Left politics in Northern Ireland. Taking the 2011 Assembly Elections as my focal point, I conducted a number of interviews with candidates and supporters, attended meetings and rallies, and participated in neighborhood canvasses. -

Coffey & Chenevix Trench

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 153 Coffey & Chenevix Trench Papers (MSS 46,290 – 46,337) (Accession No. 6669) Papers relating to the Coffey and Chenevix Trench families, 1868 – 2007. Includes correspondence, diaries, notebooks, pamphlets, leaflets, writings, personal papers, photographs, and some papers relating to the Trench family. Compiled by Avice-Claire McGovern, October 2009 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction....................................................................................................................... 4 I. Coffey Family............................................................................................................... 16 I.i. Papers of George Coffey........................................................................................... 16 I.i.1 Personal correspondence ....................................................................................... 16 I.i.1.A. Letters to Jane Coffey (née L’Estrange)....................................................... 16 I.i.1.B. Other correspondence ................................................................................... 17 I.i.2. Academia & career............................................................................................... 18 I.i.3 Politics ................................................................................................................... 22 I.i.3.A. Correspondence ........................................................................................... -

The Tyranny of the Past?

The Tyranny of the Past? Revolution, Retrospection and Remembrance in the work of Irish writer, Eilis Dillon Volumes I & II Anne Marie Herron PhD in Humanities (English) 2011 St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra (DCU) Supervisors: Celia Keenan, Dr Mary Shine Thompson and Dr Julie Anne Stevens I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of PhD in Humanities (English) is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: (\- . Anne Marie Herron ID No.: 58262954 Date: 4th October 2011 Thesis Abstract This thesis examines the extent to which Eilis Dillon's (1920-94) reliance on memory and her propensity to represent the past was, for her, a valuable motivating power and/or an inherited repressive influence in terms of her choices of genres, subject matter and style. Volume I of this dissertation consists of a comprehensive survey and critical analysis of Dillon's writing. It addresses the thesis question over six chapters, each of which relates to a specific aspect of the writer's background and work. In doing so, the study includes the full range of genres that Dillon employed - stories and novels in both Irish and English for children of various age-groups, teenage adventure stories, as well as crime fiction, literary and historical novels, short stories, poetry, autobiography and works of translation for an adult readership. The dissertation draws extensively on largely untapped archival material, including lecture notes, draft documents and critical reviews of Dillon's work. -

April 2016 Ianohio.Com 2 IAN Ohio “We’Ve Always Been Green!” APRIL 2016

April 2016 ianohio.com 2 IAN Ohio “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com APRIL 2016 Ancient Order of Hibernians Division Installs Triplet Sons of Charter Member The Amsden Triplets, from left: Alex, Father- Eric, David & Luke The Irish Brigade Division #1 of Medina are juniors at Midview High School in County Charter Member Eric Amsden Grafton, Ohio. brought his seventeen year old triplet sons to be installed in the division. Eric The division is always glad to see the was able to lead his sons in the pledge of sons of members join, but was especially the Order. The newest Hibernians are pleased to have this unique Alex, David and Luke Amsden. All three experience happen. West Side Irish American Club Upcoming Events: Live Music & Food in The Pub every Friday 6th – Wine Tasting 23rd – 1916 Easter Rising Centennial Celebration 24th – Annual Style Show & Luncheon General Meeting 3rd Thursday of every month. Since 1931 8559 Jennings Road Olmsted, Twp, Ohio 44138 440.235.5868 www.wsia-club.org APRIL 2016 “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com 3 One of my favorite people is and breaks we have received. To Editor’s Corner Pulitzer Prize winning author and those that paved the path, that columnist Regina Brett. She writes planted seeds or nurtured their with and of common sense, caring, growing, to those who received leaving the judgement at the door the honors and the appreciation, in a life well-lived and the lessons and those who did it without any learned. She says in her book, God recognition at all, I wish to say, Never Blinks, “People don’t want Thank you. -

Tenement Dublin and the 1913 Strike and Lockout: Document Pack

Unit 3: Tenement Dublin and the 1913 Strike & Lockout Document Pack Contents Source 1. PHOTOGRAPH: Belfast’s High Street in the early 1900s p. 3 [Source: National Library of Ireland, LCAB 02415] Source 2. PHOTOGRAPH: Blossom Gate, Kilmallock, County Limerick, 1909 p. 4 Source 3. MAP: Map showing the population of Irish towns in 1911 as a p. 5 percentage of their 1841 populations Source 4. FIG: The Crowded Conditions in No. 14 Henrietta Street, 1911 p.6 Source 5. MAP: Locations in Ireland and Britain associated with James p. 7 Connolly (1868–1916) Source 6. DOCUMENT: A poster calling employees of the Dublin United p. 8 Tramway Company to an Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union mass meeting at Liberty Hall, 26 July 1913 [Source: National Library of Ireland, LO P 108(27)] Source 7 DOCUMENT: A note handwritten by James Larkin on Saturday 30 p. 9 August 1913 [Source: National Library of Ireland, MS 15, 679/1/9] Source 8 DOCUMENT: Proclamation prohibiting the Sackville Street p. 10 meeting planned for 31 August 1913 [Source: Irish Labour History Society Archive] Source 9. MAP: Addressess of those arrested after ‘Bloody Sunday’ 1913 p. 11 Source Background and Captions p.12 p. 3 p. 4 p. 5 p.6 p. 7 p. 8 p. 9 p. 10 p. 11 p.12 Atlas of the Irish Revolution Resources for Schools p. 3 Caption Atlas of the Irish Revolution Resources for Schools p. 4 Caption esoes o eona oos Atlas of the Irish Revolution Resources for Schools p. 5 Caption esoes o eona oos Atlas of the Irish Revolution Resources for Schools p.