Rural Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4144R18E UNIFIL Sep07.Ai

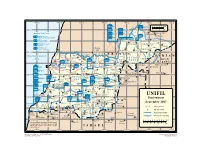

700000E 710000E 720000E 730000E 740000E 750000E 760000E HQ East 0 1 2 3 4 5 km ni MALAYSIA ta 3700000N HQ SPAIN IRELAND i 7-4 0 1 2 3 mi 3700000N L 4-23 Harat al Hart Maritime Task Force POLAND FINLAND Hasbayya GERMANY - 5 vessels 7-3 4-2 HQ INDIA Shwayya (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats, 2 auxiliaries) CHINA 4-23 GREECE - 2 vessels Marjayoun 7-2 Hebbariye (1 frigate, 1 patrol boat) Ibil 4-1 4-7A NETHERLANDS - 1 vessel as Saqy Kafr Hammam 4-7 ( ) 1 frigate 4-14 Shaba 4-14 4-13 TURKEY - 3 vessels Zawtar 4-7C (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats) Kafr Shuba ash Al Qulayah 4-30 3690000N Sharqiyat Al Khiyam Halta 3690000N tan LEBANON KHIAM Tayr Li i (OGL) 4-31 Mediterranean 9-66 4-34 SYRIAN l Falsayh SECTOR a s Bastra s Arab Sea Shabriha Shhur QRF (+) Kafr A Tura HQ HQ INDONESIA EAST l- Mine Action a HQ KOREA Kila 4-28 i Republic Coordination d 2-5 Frun a Cell (MACC) Barish 7-1 9-15 Metulla Marrakah 9-10 Al Ghajar W Majdal Shams HQ ITALY-1 At Tayyabah 9-64 HQ UNIFIL Mughr Shaba Sur 2-1 9-1 Qabrikha (Tyre) Yahun Addaisseh Misgav Am LOG POLAND Tayr Tulin 9-63 Dan Jwayya Zibna 8-18 Khirbat Markaba Kefar Gil'adi Mas'adah 3680000N COMP FRANCE Ar Rashidiyah 3680000N Ayn Bal Kafr Silm Majdal MAR HaGosherim Dafna TURKEY SECTOR Dunin BELGIUM & Silm Margaliyyot MP TANZANIA Qana HQ LUXEMBURG 2-4 Dayr WEST HQ NEPAL 8-33 Qanun HQ West BELGIUM Qiryat Shemona INDIA Houla 8-32 Shaqra 8-31 Manara Al Qulaylah CHINA 6-43 Tibnin 8-32A ITALY HQ ITALY-2 Al Hinniyah 6-5 6-16 8-30 5-10 6-40 Brashit HQ OGL Kafra Haris Mays al Jabal Al Mansuri 2-2 1-26 Haddathah HQ FRANCE 8-34 2-31 -

The Israeli-Palestenian Conflict

Karlinsky – The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict HI 393 DR. NAHUM KARLINSKY [email protected] Office hours: Elie Wiesel Center (147 Bay State Road), Room 502 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 2:30-3:30 pm; or by appointment The object of this course is to study the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, examining its origins, its major historical milestones, and the different narratives and perceptions of the conflict, viewed from the perspective of Palestinians and Israelis. We will also explore the conditions that may bring about a resolution to the conflict and reconciliation between the parties. Theoretical and comparative approaches, derives from conflict resolution and reconciliations studies, will inform our discussion. A broad array of genres and modes of expression – not only academic writings, but also literature, popular music, film, posters, documentaries, and the like – will be incorporated into this class. The course will combine lectures, classroom discussions, student presentations and in- class small group projects. We will end our course by staging an Israeli-Palestinian peace conference. Class Schedule and Readings Our basic textbooks: 1. Abdel Monem Said Aly, Khalil Shikaki, and Shai Feldman, Arabs and Israelis: Conflict and Peacemaking in the Middle East (New York: Palgrave, 2013) [available online on Mugar library's website] 2. Martin Bunton, The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) [on reserve at Mugar library] 3. Alan Dowty, Israel/Palestine, 4th Edition (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2017) [available online on Mugar library's website] 4. Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal, The Palestinian People: A History (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003) [available online on Mugar library's website] 5. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

Made in Israel: Agricultural Exports from Occupied Territories

Agricultural Made in Exports from Israel Occupied Territories April 2014 Agricultural Made in Exports from Israel Occupied Territories April 2014 The Coalition of Women for Peace was established by bringing together ten feminist peace organizations and non-affiliated activist women in Israel. Founded soon after the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000, CWP today is a leading voice against the occupation, committed to feminist principles of organization and Jewish-Palestinian partnership, in a relentless struggle for a just society. CWP continuously voices a critical position against militarism and advocates for radical social and political change. Its work includes direct action and public campaigning in Israel and internationally, a pioneering investigative project exposing the occupation industry, outreach to Israeli audiences and political empowerment of women across communities and capacity-building and support for grassroots activists and initiatives for peace and justice. www.coalitionofwomen.org | [email protected] Who Profits from the Occupation is a research center dedicated to exposing the commercial involvement of Israeli and international companies in the continued Israeli control over Palestinian and Syrian land. Currently, we focus on three main areas of corporate involvement in the occupation: the settlement industry, economic exploitation and control over population. Who Profits operates an online database which includes information concerning companies that are commercially complicit in the occupation. Moreover, the center publishes in-depth reports and flash reports about industries, projects and specific companies. Who Profits also serves as an information center for queries regarding corporate involvement in the occupation – from individuals and civil society organizations working to end the Israeli occupation and to promote international law, corporate social responsibility, social justice and labor rights. -

Curriculum Vitae

Name: Dafna Regev Date: 22.1.20 CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Details Permanent Home Address: 92 Azmon, Misgav Mobile Post 20170, Israel Home Telephone Number: 04-9909201 Office Telephone Number: 04-8280773 Cellular Phone: 052-6364163 E-mail Address: [email protected] 2. Higher Education A. Undergraduate and Graduate Studies Period of Name of Institution and Department Degree Study 1992-1995 Psychology and Special Education, University of Haifa B.A. 1996-2000 Special Education (Creative Art Therapies), University of M.A. Haifa 1996-1998 Art Therapy, Complementary Track in Education, A.T.R University of Haifa 2000-2005 Department of Education, University of Haifa Ph.D. 2007 – 2010 Department of Psychology, Psychotherapy (focus on Psychotherapist children and youth), University of Haifa 2 2015 – 2017 The Israel Winnicott Center (IWC) Advanced studies in psychotherapy B. Post-Doctoral Studies Period of Name of Institution and Department/Lab Name of Host Study 2010 – 2012 The Bob Shapell School of Social Work, Tel-Aviv Prof. Tamie University Ronen 1 3. Academic Ranks and Tenure in Institutes of Higher Education Years Name of Institution and Department Rank/Position 2003-2005 Ohalo College, Katzrin, Israel Lecturer; Non-faculty 2003-2008 Special Education, University of Haifa, Israel Teaching Fellow 2005-2009 Teacher Training College, Sakhnin, Israel Tenured Lecturer 2009-2011 Tel-Hai College, Israel Tenured Lecturer 2009-2011 The School of Creative Art Therapies, University of Haifa, Teaching Israel Fellow 9 2011-present The School of Creative Art Therapies, University of Haifa, Senior Israel Lecturer Note: * represents activities and publications since appointment to Senior Lecturer. 4. -

SPRING 2009 • YU REVIEW Yeshiva College Bernard Revel Graduate School Ferkauf Graduate School of Psychology Benjamin N

Albert Einstein College of Medicine Stern College for Women class notes Wurzweiler School 1950s pediatrics at Einstein. He is a past director of newborn services at the YUReview welcomes Classnotes submissions that are typewritten or neatly Mazal tov to Dr. Mel ’57YC and Debby Weiler Hospital of the Albert Einstein ’55YUHS Adler, and Arthur and Niki College of Medicine. printed. Relevant information (name, maiden name, school, year of graduation, Fuchs on the birth of twin grandsons, Mazal tov to Libby Kahane ’55YUHS, Yaakov Yehoshua and Shmuel Reuven. who just completed “ Rabbi Meir and a contact phone number) must be included. The magazine is not The proud parents are Zevi ’92YC and Kahane: His Life and Thought,” a Leslie (Fuchs) ’94SCW Adler. responsible for incomplete or in correct informa tion. Graduates of Cardozo, book on the life of her late husband. Mazal tov to Rabbi Aaron ’55YC, IBC, Mazal tov to Meyer Lubin, ’58FGS on Wurzweiler, Ferkauf, and Einstein may also direct notes to those schools’ ’59BRGS, RIETS and his wife Pearl the publication of his collection of ’52YUHS Borow on the marriages of essays, “Thrilling Torah Discoveries.” alumni publications. In addition to professional achievements, YUReview their grandsons Chaim and Uri to Tzivia Nudel and Dina Levy, Mazal tov to Seymour Moskowitz Classnotes may contain alumni family news, including information on births, respectively. ’54YC, ’56RIETS on the recent publi - cation of two books: “Falcon of the marriages, condolences, and ba r/bat mitzvahs. Engagement announcements The accomplishments of Dr. Leon Quraysh,” a historical novel depicting Chameides ’51YUHS, ’55YC, TI, IBC, the eighth century Muslim conquest of are not accepted. -

Israel a History

Index Compiled by the author Aaron: objects, 294 near, 45; an accidental death near, Aaronsohn family: spies, 33 209; a villager from, killed by a suicide Aaronsohn, Aaron: 33-4, 37 bomb, 614 Aaronsohn, Sarah: 33 Abu Jihad: assassinated, 528 Abadiah (Gulf of Suez): and the Abu Nidal: heads a 'Liberation October War, 458 Movement', 503 Abandoned Areas Ordinance (948): Abu Rudeis (Sinai): bombed, 441; 256 evacuated by Israel, 468 Abasan (Arab village): attacked, 244 Abu Zaid, Raid: killed, 632 Abbas, Doa: killed by a Hizballah Academy of the Hebrew Language: rocket, 641 established, 299-300 Abbas Mahmoud: becomes Palestinian Accra (Ghana): 332 Prime Minister (2003), 627; launches Acre: 3,80, 126, 172, 199, 205, 266, 344, Road Map, 628; succeeds Arafat 345; rocket deaths in (2006), 641 (2004), 630; meets Sharon, 632; Acre Prison: executions in, 143, 148 challenges Hamas, 638, 639; outlaws Adam Institute: 604 Hamas armed Executive Force, 644; Adamit: founded, 331-2 dissolves Hamas-led government, 647; Adan, Major-General Avraham: and the meets repeatedly with Olmert, 647, October War, 437 648,649,653; at Annapolis, 654; to Adar, Zvi: teaches, 91 continue to meet Olmert, 655 Adas, Shafiq: hanged, 225 Abdul Hamid, Sultan (of Turkey): Herzl Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Jewish contacts, 10; his sovereignty to receive emigrants gather in, 537 'absolute respect', 17; Herzl appeals Aden: 154, 260 to, 20 Adenauer, Konrad: and reparations from Abdul Huda, Tawfiq: negotiates, 253 Abdullah, Emir: 52,87, 149-50, 172, Germany, 279-80, 283-4; and German 178-80,230, -

![Income Tax Ordinance [New Version] 5721-1961](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4190/income-tax-ordinance-new-version-5721-1961-2334190.webp)

Income Tax Ordinance [New Version] 5721-1961

Disclaimer : The Following is an unofficial translation, and not necessarily an updated one. The binding version is the official Hebrew text. Readers are consequently advised to consult qualified professional counsel before making any decision in connection with the enactment, which is here presented in translation for their general information only. INCOME TAX ORDINANCE [NEW VERSION] 5721-1961 PART ONE – INTERPRETATION Definitions 1. In this Ordinance – "person" – includes a company and a body of persons, as defined in this section; "house property", in an urban area – within its meaning in the Urban Property Ordinance 1940; "Exchange" – a securities exchange, to which a license was given under section 45 of the Securities Law, or a securities exchange abroad, which was approved by whoever is entitled to approve it under the statutes of the State where it functions, and also an organized market – in Israel or abroad – except when there is an explicitly different provision; "spouse" – a married person who lives and manages a joint household with the person to whom he is married; "registered spouse" – a spouse designated or selected under section 64B; "industrial building ", in an area that is not urban – within its meaning in the Rural Property Tax Ordinance 1942; "retirement age" – the retirement age, within its meaning in the Retirement Age Law 5764-2004; "income" – a person's total income from the sources specified in sections 2 and together with amounts in respect of which any statute provides that they be treated as income for purposes -

Relationships Between the Therapeutic Alliance and Reactions to Artistic Experience with Art Materials in an Art Therapy Simulation

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 14 July 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.560957 Relationships Between the Therapeutic Alliance and Reactions to Artistic Experience With Art Materials in an Art Therapy Simulation Inbal Gazit 1*, Sharon Snir 2, Dafna Regev 1 and Michal Bat Or 1 1 The School of Creative Arts Therapies, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel, 2 Department of Art Therapy, Tel Hai College, Upper Galilee, Israel In art therapy, art-making plays an important role in the therapeutic relationship. To better understand the triangular relationship between the art therapist, the client and the artwork, this study investigated the association between the therapeutic alliance and reactions to artistic experiences with art materials in an art therapy simulation. The simulation consisted of a series of 6–8 sessions in which art therapy students were divided into teams composed of a permanent observer (art therapist) and creator (client). The client’s role was to self-explore through art- making, and the art therapist’s role was Edited by: to accompany the client. Thirty-four students, all women, who played the art therapist Vicky (Vassiliki) Karkou, Edge Hill University, United Kingdom role, and 37 students (one male) who played the client participated in the study. Of these Reviewed by: participants, there were 24 pairs where both participants filled out all the questionnaires. Michelle Winkel, A short version of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI) was completed by the clients and Canadian International Institute of Art the art therapists on the second session (T1) and on the penultimate session (T2). The Therapy, Canada Joanne Powell, clients also completed the Art-Based Intervention Questionnaire (ABI) at T2. -

Healing the Holy Land: Interreligious Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine

Healing the Holy Land Interreligious Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine Yehezkel Landau United States Institute of Peace Contents Summary 5 Foreword by David Smock 7 1. Introduction 9 2. Religion: A Blessing or a Curse? 11 3. After the Collapse of Oslo 13 4. The Alexandria Summit and Its Aftermath 16 5. Grassroots Interreligious Dialogues 26 6. Educating the Educators 29 7. Other Muslim Voices for Interreligious Peacebuilding 31 8. Symbolic Ritual as a Mode of Peacemaking 35 9. Active Solidarity: Rabbis for Human Rights 38 10. From Personal Grief to Collective Compassion 41 11. Journeys of Personal Transformation 44 12. Practical Recommendations 47 Appendices 49 About the Author 53 About the Institute 54 Summary ven though the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is primarily a political dispute between two nations over a common homeland, it has religious aspects that Eneed to be addressed in any effective peacemaking strategy. The peace agenda cannot be the monopoly of secular nationalist leaders, for such an approach guarantees that fervent religious believers on all sides will feel excluded and threatened by the diplo- matic process. Religious militants need to be addressed in their own symbolic language; otherwise, they will continue to sabotage any peacebuilding efforts. Holy sites, including the city of Jerusalem, are claimed by both peoples, and deeper issues that fuel the conflict, including the elements of national identity and purpose, are matters of transcendent value that cannot be ignored by politicians or diplomats. This report argues for the inclusion of religious leaders and educators in the long-term peacebuilding that is required to heal the bitter conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. -

5?+39W2 2 1 July 2006 Chinese Original: English 5/2006/560

Disk.: General 5?+39w2 2 1 July 2006 Chinese Original: English 5/2006/560 2 S/2006/560 3 S/2006/560 4 S/2006/560 5 S/2006/560 6 S/2006/560 7 S/2006/560 8 S/2006/560 9 700000E 710000E 720000E 730000E 740000E 750000E 760000E 0 1 2 3 4 5 km 3700000N 0 1 2 3 mi 3700000N HQ INDIA Harat al Hart Hasbayya 4-2 Shwayya Marjayoun Ibil Hebbariye 4-1 as 4-7A 4-7 Saqy Kafr Hammam 4-14 4-14 4-7C Shaba Al Khiyam Kafr Shuba 4-13 Zawtar ash Sharqiyat Al Qulayah 4-30 3 000 3 000 690 N Halta 690 N an LEBANON KHIAM 4-31 Tayr Lit i Mediterranean 9-66 (OGL) SYRIAN l Falsayh a s INDBATT Bastra s Arab Sea Shhur A Shabriha Tura FMR l- Mine Action a 9-15 4-28 i Republic Coordination d Frun a Cell (MACC) Metulla Marakah Barish Kafr Kila W Majdal Shams 9-1 At Tayyabah 9-64 Al Ghajar HQ UNIFIL Sur 9-10 Mughr Shaba (Tyre) Yahun Tulin Addaisseh Misgav Am LOG POLAND Tayr Qabrikha 9-63 Dan Mas'adah Ar Rashidiyah Zibna Markaba Kefar Gil'adi 9-66 3680000N COMP FRANCE Jwayya 8-18 Majdal 9-1 3680000N Kafr 9-1 Ayn Bal Khirbat Silm MAR HaGosherim Dafna MP COMPOSITE Dayr Dunin (OGL) Margaliyyot Qana Silm 8-33 Qanun 8-31 HQ GHANA INDIA Hula Qiryat Shemona Shaqra 8-32 Al Qulaylah HQ CHINA 6-43 Tibnin 8-32A Manara 6-16 ITALY 6-5 Al Hinniyah 6-40 POLAND 5-10 Kafra a*. -

Bulletin 69-70

bulletin 69-70 International Sociological Association Association Internationale de Sociologie Asociación Internacional de Sociología Faculty of Political Sciences and Sociology University Complutense 28223 Madrid, Spain. Tel: (34-1)3527650. Fax: (34-1)3524945. Email: [email protected] http://www.ucm.es/OTROS/isa o Letter from the President, No. 4 1 Immanuel Wallerstein o ISA Regional Conferences 4 o Declaración final del XX Congreso 5 de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Sociología o Sociologists and their Work 7 by Stella R. Quah, ISA Vice-President (Research) o Reports from the Research Committees 9 o Reports from the Working Groups 28 o Reports from the Thematic Groups 29 o Call for Participation and Papers 30 o Calendar of Future Events 32 o ISA membership form 35 o Publications of the ISA 37 Spring-Summer 1996 Published by the International Sociological Association ISSN 0383-8501 Editor:Izabela Barlinska. Lay-out: José Ignacio Reguera. Printed by Fotocopias Universidad S.A. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 1994-1998 President: Layi Erinosho Arnaud Sales, Christine Inglis Immanuel Wallerstein Ogun State University Binghamton University Ijeby-Ode, Nigeria Research Coordinating Binghamton, NY, USA Committee Vincenzo Ferrari Chair: Stella R. Ouah, Members: Vice-President, Program University of Milano Linda Christiansen-Ruffman, Alberto Martinelli Milano, Italy Vincenzo Ferrari, Jan Marie Fritz University of Milano Jorge A. González, Christine Inglis Milano, Italy Jan Marie Fritz Jennifer Platt, Arnaud Sales, Piotr University of Cincinnati Sztompka Vice-President, Research Cincinnati,OH, USA Council Publications Committee Stella R. Ouah Jorge González Chair: James Beckford National University of Singapore Universidad Colima Member: Karl van Meter, France Singapore Colima, Mexico EC representatives: Layi Erinosho, Nigeria, Bernadette Vice-President, Publications Christine Inglis Bawin-Legros, Belgium James A.