The Palestinian Refugees’ “Right to Return” and the Peace Process, 20 B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel by Sydney Fisher

R EVIEW D IGEST: H UMAN R IGHTS & T HE W AR ON T ERROR Israel by Sydney Fisher Israel and Palestine have been in an “interim period” between full scale occupation and a negotiated end to the conflict for a long time. This supposedly intermediate period in the conflict has seen no respite from violations of Palestinians’ human rights or the suicide bombings affecting Israelis. This section will provide resources spanning the issues regarding Israel, Palestine and how the human rights dimensions of this conflict interact with the war on terror. The issue of how both sides will arrive at peace remains a mystery. Background Marek Arnaud. 2003. “The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Is There a Way Out?” Australian Journal of International Affairs. 57(2): 243. ABSTRACT: States that the blame for the inability to put an end to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians must be shared by all parties. Discusses issues of trust and U.S. involvement under both Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Joel Beinin. 2003. “Is Terrorism a Useful Term in Understanding the Middle East and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict?” Radical History Review. 12. ABSTRACT: Examines the definition of the term “terrorism” in the context of the Middle East and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Politically motivated violence directed against civilian populations and atrocities committed in the course of repressing anticolonial rebellions. Shlomo Hasson. 1996. “Local Politics and Split Citizenship in Jerusalem.” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research. 20(1): 116. ABSTRACT: Explores the relationship between ethno-national conflict, local politics and citizenship rights in Jerusalem. -

The Pragmatic Dimension of the Palestinian Hamas: a Network Perspective

Mishal 569 The Pragmatic Dimension of the Palestinian Hamas: A Network Perspective SHAUL MISHAL n the wake of the 11 September attack on the World Trade Center in INew York and President Bush’s “war on terrorism,” it is important to try to understand the cultural, political, and social dimensions of such radical Islamic groups as the Palestinian Hamas. Within political and academic circles in the Western world, it is common to portray Islamic movements in categorical terms that utilize binary classifications that mark real or imaginary social attributes rather than relational patterns.1 Much of this perception derives from the violence accompanying Islamic reli- gious fervor and the fanaticism marking some of its groups and regimes, raising fears of “a clash of civilizations” and “a threat” to Western liberal democratic values and social order.2 Hamas, an abbreviation of Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya (Is- lamic Resistance Movement), did not escape the binary perception, and has been described solely as a movement identified with Islamic funda- mentalism and suicide bombings. The objectives at the top of its agenda are the liberation of Palestine through a holy war (jihad) against Israel, establishing an Islamic state on its soil, and reforming society in the spirit of true Islam. It is this Islamic vision, combined with its nationalist claims and militancy toward Israel, that accounts for the prevailing image of Hamas as a rigid movement, ready to pursue its goals at any cost, with no limits or constraints. Islamic and national zeal, bitter opposition to the SHAUL MISHAL teaches at the Department of Political Science at Tel Aviv University, where his research focuses on Arab and Palestinian politics. -

Annual Report (PDF)

1 TABLE OF Pulling Together CONTENTS Nowhere did we see a greater display of unity coalescence than in the way AMIT pulled together President’s Message 03 during the pandemic in the early months of 2020. While this annual report will share our proud UNITY in Caring for Our accomplishments in 2019, when the health crisis Most Vulnerable Kids 04 hit, many opportunities arose for unity, which was UNITY in Educational expressed in new and unexpected ways within AMIT. Excellence 05 Since its inception 95 years ago, AMIT has faced its Academy of challenges. Through thick and thin, wars and strife, Entrepreneurship & Innovation 06 and the big hurdles of this small nation, AMIT has been steadfast in its vision and commitment to educate AMIT’s Unique children and create the next generation of strong, Evaluation & Assessment Platform 07 proud, and contributing Israeli citizens. UNITY in Leveling the That Vision Playing Field 08 Has Real Results UNITY in Zionism 09 In 2019, AMIT was voted Israel’s #1 Educational Network for the third year in a row. Our bagrut diploma UNITY in rate climbed to 86 percent, outpacing the national rate Jewish Values 10 of 70 percent. Our students brought home awards Your Impact 11 and accolades in academics, athletics, STEM-centered competitions, and more. Financials 13 And then in the early months of 2020 with the onset Dedications 15 of the pandemic, instead of constricting in fear and uncertainty, AMIT expanded in a wellspring of giving, Board of Directors 16 creativity, and optimism. Students jumped to do chesed Giving Societies 17 to help Israel’s most vulnerable citizens and pivoted to an online distance learning platform during the two months schools were closed. -

The Origins of Hamas: Militant Legacy Or Israeli Tool?

THE ORIGINS OF HAMAS: MILITANT LEGACY OR ISRAELI TOOL? JEAN-PIERRE FILIU Since its creation in 1987, Hamas has been at the forefront of armed resistance in the occupied Palestinian territories. While the move- ment itself claims an unbroken militancy in Palestine dating back to 1935, others credit post-1967 maneuvers of Israeli Intelligence for its establishment. This article, in assessing these opposing nar- ratives and offering its own interpretation, delves into the historical foundations of Hamas starting with the establishment in 1946 of the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood (the mother organization) and ending with its emergence as a distinct entity at the outbreak of the !rst intifada. Particular emphasis is given to the Brotherhood’s pre-1987 record of militancy in the Strip, and on the complicated and intertwining relationship between the Brotherhood and Fatah. HAMAS,1 FOUNDED IN the Gaza Strip in December 1987, has been the sub- ject of numerous studies, articles, and analyses,2 particularly since its victory in the Palestinian legislative elections of January 2006 and its takeover of Gaza in June 2007. Yet despite this, little academic atten- tion has been paid to the historical foundations of the movement, which grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Gaza branch established in 1946. Meanwhile, two contradictory interpretations of the movement’s origins are in wide circulation. The !rst portrays Hamas as heir to a militant lineage, rigorously inde- pendent of all Arab regimes, including Egypt, and harking back to ‘Izz al-Din al-Qassam,3 a Syrian cleric killed in 1935 while !ghting the British in Palestine. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Duncan Kennedy, Harvard Law School, Israel/Palestine Legal Issues, Fall 2007

Is pal full syll 11/07/07 Seminar Israel/Palestine Legal Issues Syllabus Duncan Kennedy Course Summary Class 1: Historical background up to 1949 Part one: Inside Israel Class 2: The legalities of the appropriation of Palestinian land Class 3: The public law structure of the Israeli polity: “Jewish and democratic” Class 4: The issue of discrimination against the Arab minority Part two: The West Bank and Gaza Class 5: Legal status of the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and of Israeli settlements Class 6: The issue of the duties of the occupier with respect to social and economic development: before Oslo and after Oslo Class 7: Are the settlements occupation or de facto annexation? Class 8: Palestinian resistance: the legality or not of violence in response to occupation Class 9: The targets and techniques of armed resistance: the issue of Palestinian violations of international humanitarian law Class 10: The legality or not of Israeli responses to Palestinian resistance Part Three: Legal dimensions of deal breaking issues Class 11: Sovereighty: The status of Jerusalem and the binational state proposal Class 12: The right of return as a legal issue Class 1: Historical background Historical documents (except for the Fourteen Points, all are from The Israel-Arab Reader (Walter Laqueur & Barry Rubin, eds.)) 1 The Fourteen Points from Wikipedia Sykes-Picot agreement MacMahon letter Balfour Declaration Emir Faisal – Chaim Weizmann agreement League of Nations Mandate for Palestine Israeli Declaration of Independence U.N. Resolutions 194 & 303 Israeli Law of Return Aaron Wolf, Hydropolitics along the Jordan River: Scarce Water and its Impact on the Arab-Israeli Conflict (New York: United Nations University Press, 1995) (background summary) Nur Masalha, The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem (London: Pluto Press, 2003), ch. -

Fatah Congress: Will New Resolutions Mean a New Direction?

PolicyWatch #1569 Fatah Congress: Will New Resolutions Mean a New Direction? By Mohammad Yaghi August 14, 2009 PolicyWatch #1569 is the second in a two-part series examining the political and organizational implications of Fatah's recently concluded General Congress. This part explores Fatah's external dynamics, specifically how the group's new political program will affect its relations with Israel, Hamas, and the Palestinian Authority. PolicyWatch #1568 examines Fatah's internal dynamics, particularly in regard to its top leader Mahmoud Abbas. At its recently concluded General Congress, Fatah established a new political program that will affect both its terms of reengagement with Israel and its relations with Hamas and the Palestinian Authority (PA). Fatah's new constraints on negotiations with Israel, however, may harm Mahmoud Abbas -- PA president and the party's top leader -- who needs to respond positively to international peace initiatives that may conflict with the organization's new rules of engagement. Abbas might ignore these congressional decisions, believing its program is intended only for internal consumption to fend off the accusations of the party's hardline members. Fatah's renewed efforts to reunite the West Bank and Gaza could lead to an escalation with Hamas, since many observers doubt unity can be achieved peacefully. Fatah's Political Program According to al-Ayyam newspaper, Fatah's new political program sets demanding terms for reengagement with Israel, even more so than those Abbas has been stating publicly since Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu took office earlier this year. The new terms include a complete halt of Israeli settlement construction, especially in East Jerusalem; an Israeli withdrawal from all Palestinian cities, reverting back to the status that existed before the September 2000 intifada; a clear and binding timetable for negotiations; a refusal to postpone negotiations over Jerusalem and refugees; and an insistence on a defined mechanism for arbitration. -

Israel I Palestina Diversos Territoris, Dues Nacions I Una Disputa

Israel i Palestina Diversos territoris, dues nacions i una disputa Arret d’Arreug i Pau Treball de Recerca Octubre de 2020 2n de Batxillerat Israel i Palestina: Diversos territoris, dues nacions i una disputa ÍNDEX AGRAÏMENTS 5 OBJECTIUS 6 INTRODUCCIÓ 7 BLOC I: DE L’ORIGEN A LA VIOLÈNCIA 9 1. CONTEXT HISTÒRIC 10 1.1. L’estima jueu cap a l’anomenada terra promesa 11 1.2. Judea, província romana 15 1.3. Els Àrabs, les Croades i l’Imperi Otomà 16 1.4. El Sionisme original 17 1.5. El Sionisme polític 18 2. ISRAEL, DE NACIÓ A PAÍS 20 2.1. Introducció 21 2.2. Un origen envoltat de conflictes 22 2.3. El “mes cruel” 24 2.4. Els britànics es plantegen cedir el protectorat 25 2.5. Batalla de Haifa 26 3. ISRAEL, UNA QÜESTIÓ INTERNACIONAL 27 3.1. Predeclaració d’independència israelí 28 3.2. Proclamació d’independència d’Israel 28 3.3. Conflictes postindependència 29 3.4. Entrada d’Egipte a la guerra 30 3.5. Jerusalem al maig del 48 31 3.6. Finals de maig 32 3.7. Gran aturament del foc del 48 33 3.8. La primera treva (juny del 48) 33 3.9. L’Altalena 34 3.10. Expansions després de la unificació jueva 34 3.11. Lod i Ramla 35 3.12. Folke Bernadotte, mediador de l’ONU 36 3.13. Nègueb I 37 3.14. Operació Hiram 37 2 Israel i Palestina: Diversos territoris, dues nacions i una disputa 3.15. Nègueb II 38 3.16. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87598-1 - The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948, Second Edition Edited by Eugene L. Rogan and Avi Shlaim Excerpt More information Introduction The Palestine War lasted less than twenty months, from the United Nations resolution recommending the partition of Palestine in November 1947 to the final armistice agreement signed between Israel and Syria in July 1949. Those twenty months transformed the political landscape of the Middle East forever. Indeed, 1948 may be taken as a defining moment for the region as a whole. Arab Palestine was destroyed and the new state of Israel established. Egypt, Syria and Lebanon suffered outright defeat, Iraq held its lines, and Transjordan won at best a pyrrhic victory. Arab public opinion, unprepared for defeat, let alone a defeat of this magnitude, lost faith in its politicians. Within three years of the end of the Palestine War, the prime ministers of Egypt and Lebanon and the king of Jordan had been assassinated, and the president of Syria and the king of Egypt over- thrown by military coups. No event has marked Arab politics in the second half of the twentieth century more profoundly. The Arab–Israeli wars, the Cold War in the Middle East, the rise of the Palestinian armed struggle, and the politics of peace-making in all of their complexity are a direct con- sequence of the Palestine War. The significance of the Palestine War also lies in the fact that it was the first challenge to face the newly independent states of the Middle East. -

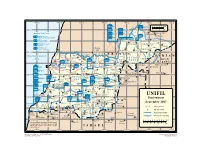

4144R18E UNIFIL Sep07.Ai

700000E 710000E 720000E 730000E 740000E 750000E 760000E HQ East 0 1 2 3 4 5 km ni MALAYSIA ta 3700000N HQ SPAIN IRELAND i 7-4 0 1 2 3 mi 3700000N L 4-23 Harat al Hart Maritime Task Force POLAND FINLAND Hasbayya GERMANY - 5 vessels 7-3 4-2 HQ INDIA Shwayya (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats, 2 auxiliaries) CHINA 4-23 GREECE - 2 vessels Marjayoun 7-2 Hebbariye (1 frigate, 1 patrol boat) Ibil 4-1 4-7A NETHERLANDS - 1 vessel as Saqy Kafr Hammam 4-7 ( ) 1 frigate 4-14 Shaba 4-14 4-13 TURKEY - 3 vessels Zawtar 4-7C (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats) Kafr Shuba ash Al Qulayah 4-30 3690000N Sharqiyat Al Khiyam Halta 3690000N tan LEBANON KHIAM Tayr Li i (OGL) 4-31 Mediterranean 9-66 4-34 SYRIAN l Falsayh SECTOR a s Bastra s Arab Sea Shabriha Shhur QRF (+) Kafr A Tura HQ HQ INDONESIA EAST l- Mine Action a HQ KOREA Kila 4-28 i Republic Coordination d 2-5 Frun a Cell (MACC) Barish 7-1 9-15 Metulla Marrakah 9-10 Al Ghajar W Majdal Shams HQ ITALY-1 At Tayyabah 9-64 HQ UNIFIL Mughr Shaba Sur 2-1 9-1 Qabrikha (Tyre) Yahun Addaisseh Misgav Am LOG POLAND Tayr Tulin 9-63 Dan Jwayya Zibna 8-18 Khirbat Markaba Kefar Gil'adi Mas'adah 3680000N COMP FRANCE Ar Rashidiyah 3680000N Ayn Bal Kafr Silm Majdal MAR HaGosherim Dafna TURKEY SECTOR Dunin BELGIUM & Silm Margaliyyot MP TANZANIA Qana HQ LUXEMBURG 2-4 Dayr WEST HQ NEPAL 8-33 Qanun HQ West BELGIUM Qiryat Shemona INDIA Houla 8-32 Shaqra 8-31 Manara Al Qulaylah CHINA 6-43 Tibnin 8-32A ITALY HQ ITALY-2 Al Hinniyah 6-5 6-16 8-30 5-10 6-40 Brashit HQ OGL Kafra Haris Mays al Jabal Al Mansuri 2-2 1-26 Haddathah HQ FRANCE 8-34 2-31 -

6-194E.Pdf(6493KB)

Samuel Neaman Eretz Israel from Inside and Out Samuel Neaman Reflections In this book, the author Samuel (Sam) Neaman illustrates a part of his life story that lasted over more that three decades during the 20th century - in Eretz Israel, France, Syria, in WWII battlefronts, in Great Britain,the U.S., Canada, Mexico and in South American states. This is a life story told by the person himself and is being read with bated breath, sometimes hard to believe but nevertheless utterly true. Neaman was born in 1913, but most of his life he spent outside the country and the state he was born in ERETZ and for which he fought and which he served faithfully for many years. Therefore, his point of view is from both outside and inside and apart from • the love he expresses towards the country, he also criticizes what is going ERETZ ISRAELFROMINSIDEANDOUT here. In Israel the author is well known for the reknowned Samuel Neaman ISRAEL Institute for Advanced Studies in Science and Technology which is located at the Technion in Haifa. This institute was established by Neaman and he was directly and personally involved in all its management until he passed away a few years ago. Samuel Neaman did much for Israel’s security and FROM as a token of appreciation, all IDF’s chiefs of staff have signed a a megila. Among the signers of the megila there were: Ig’al Yadin, Mordechai Mak- lef, Moshe Dayan, Haim Laskov, Zvi Zur, Izhak Rabin, Haim Bar-Lev, David INSIDE El’arar, and Mordechai Gur. -

The Israeli-Palestenian Conflict

Karlinsky – The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict HI 393 DR. NAHUM KARLINSKY [email protected] Office hours: Elie Wiesel Center (147 Bay State Road), Room 502 Tuesdays and Thursdays, 2:30-3:30 pm; or by appointment The object of this course is to study the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, examining its origins, its major historical milestones, and the different narratives and perceptions of the conflict, viewed from the perspective of Palestinians and Israelis. We will also explore the conditions that may bring about a resolution to the conflict and reconciliation between the parties. Theoretical and comparative approaches, derives from conflict resolution and reconciliations studies, will inform our discussion. A broad array of genres and modes of expression – not only academic writings, but also literature, popular music, film, posters, documentaries, and the like – will be incorporated into this class. The course will combine lectures, classroom discussions, student presentations and in- class small group projects. We will end our course by staging an Israeli-Palestinian peace conference. Class Schedule and Readings Our basic textbooks: 1. Abdel Monem Said Aly, Khalil Shikaki, and Shai Feldman, Arabs and Israelis: Conflict and Peacemaking in the Middle East (New York: Palgrave, 2013) [available online on Mugar library's website] 2. Martin Bunton, The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) [on reserve at Mugar library] 3. Alan Dowty, Israel/Palestine, 4th Edition (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2017) [available online on Mugar library's website] 4. Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal, The Palestinian People: A History (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003) [available online on Mugar library's website] 5.