BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Versus Intramuscular Administration of Vitamin B12 for Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Primary Care: a Pragmatic, Randomised, Non-Inferiority Clinical Trial (OB12)

Open access Original research BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033687 on 20 August 2020. Downloaded from Oral versus intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency in primary care: a pragmatic, randomised, non- inferiority clinical trial (OB12) Teresa Sanz- Cuesta ,1,2 Esperanza Escortell- Mayor,1,2 Isabel Cura- Gonzalez ,1,2,3 Jesus Martin- Fernandez,2,3,4 Rosario Riesgo- Fuertes,2,5 Sofía Garrido- Elustondo,2,6 Jose Enrique Mariño- Suárez,7 Mar Álvarez- Villalba,2,8 Tomás Gómez- Gascón,2,9 Inmaculada González- García,10 Paloma González- Escobar,11 Concepción Vargas- Machuca Cabañero,12 Mar Noguerol-Álvarez,13 Francisca García de Blas- González,2,14 Raquel Baños- Morras,11 Concepción Díaz- Laso,15 Nuria Caballero- Ramírez,16 Alicia Herrero de- Dios,17 Rosa Fernández- García,18 Jesús Herrero- Hernández,19 Belen Pose- García,14 20 20 20 To cite: Sanz- Cuesta T, María Luisa Sevillano- Palmero, Carmen Mateo- Ruiz, Beatriz Medina- Bustillo, 21 Escortell- Mayor E, Cura- Monica Aguilar- Jiménez, and OB12 Group Gonzalez I, et al. Oral versus intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency in primary care: ABSTRACT a pragmatic, randomised, Strengths and limitations of this study non- inferiority clinical Objectives To compare the effectiveness of oral versus trial (OB12). BMJ Open intramuscular (IM) vitamin B (VB12) in patients aged ≥65 12 ► This is the largest and longest follow-up randomised 2020; :e033687. doi:10.1136/ years with VB12 deficiency. 10 clinical trial in patients aged ≥65 years with VB12 bmjopen-2019-033687 Design Pragmatic, randomised, non- inferiority, deficiency. -

Cómo Destacar Como Promotor Inmobiliario

CDC PIN – CÓMO DESTACAR COMO PROMOTOR INMOBILIARIO Fechas: 10 de noviembre al 28 de junio del 2021. Horario: 17:00 a 21:00 h. Horas lectivas: 232 h Modalidad: online (streaming) 1. EQUIPO DOCENTE DIRECTOR FERNANDO CATALÁN DE OCÓN Presidente ejecutivo CIARE COAM (ÁREA INMOBILIARIA) Instituto FORMACIÓN Continua Cl. Hortaleza, 63 Madrid T.: 915 951 537 [email protected] http://www.coam.org/es/formacion MÓDULO 0 CONOCIMIENTOS IMPRESCINDIBLES ECONÓMICO-FINANCIEROS, NECESARIOS Y SUFICIENTES, PARA ABORDAR, CON ÉXITO, EL PROGRAMA CDC PIN o Roberto Vicente Director de Negocio y Expansión. INGESCASA o Teo Arranz Director. PRÓXIMA REAL ESTATE o Luis Alaejos Coordinador de Inversiones y Desarrollos Inmobiliarios. SAREB Instituto FORMACIÓN Continua Cl. Hortaleza, 63 Madrid T.: 915 951 537 [email protected] http://www.coam.org/es/formacion MÓDULO 1 CASO TRONCAL E INTERDISCIPLINAR DE UNA PROMOCIÓN COMPLETA (con clases en TODAS las semanas del Programa) o Francisco Sánchez Consultor y Promotor inmobiliario MÓDULO 2 OBJETO SOCIAL, ORGANIZACIÓN, ESTRUCTURA Y FUNCIONAMIENTO DE UNA PROMOTORA INMOBILIARIA. RSC o Teresa Marzo Directora General de Negocio. VÍA CÉLERE o Raúl Guerrero CEO. GESTILAR Instituto FORMACIÓN Continua Cl. Hortaleza, 63 Madrid T.: 915 951 537 [email protected] http://www.coam.org/es/formacion o Majda Labied Directora General. KRONOS HOMES RSC (RESPONSABILIDAD SOCIAL CORPORATVA) o Carlos Valdés ExDirector RSC. VÍA CÉLERE MÓDULO 3 ESTRATEGIA DE LA COMPAÑÍA o Juan Velayos Presidente y CEO. JV20 Instituto FORMACIÓN Continua Cl. Hortaleza, 63 Madrid T.: 915 951 537 [email protected] http://www.coam.org/es/formacion o Miguel Ángel Peña Director de Residencial. GRUPO LAR o César Barrasa Director de Proyectos Estratégicos. -

Fuencarral-El Pardo

Distrito 08 - Fuencarral-El Pardo 81 88 Barrios 86 81 - El Pardo 87 166 166 82 - Fuentelarreina 83 - Peñagrande 82 214 84 - Pilar 85 85 - La Paz 83 84 56159 164 86 - Valverde 96 95 93 64 87 - Mirasierra 88 - El Goloso 055 163 215 Dirección General de Estadística 060663 Distrito 08 - Fuencarral-El Pardo • 4 130 2 1 129 3 128 169 167 165 164 161 170 168 91 159 160 162 114 131 171 153 172 Barrios 139 135 152 121 166 147 125 158 124 132 122 108 136 116 126 115 120 123 133 117 115 155 114 113 111 117 107 81 - El Pardo 137 134 119 110 35 112 92 93 111 99 82 - Fuentelarreina 156 163 154 138 36 110 144 109106 143 41 146 106 112 17 37 40 108 105 116 142 33 39 42 102 14014 19 38 43 107104 141 18 32 34 44 100 173 109 214 83 - Peñagrande 5 145 151 150 171 16 20 28 31 103 15 21 30 170 182 12 27 29 99 168 28 232226 45 167 176 90 25 93 93 86 87 13 11 149 47 78 92 166165164 69 65 84 - Pilar 24 46 778179 94 95 85 66 6 48 76 80 91 92 172 64 10 7469758382 878889 98 94 163 88 67 63 62 49 7273 8586 96 72 7 67 84 57 90 89 71 61 9 50 7166 59 97 91 101 83 73 60 55 8 58 161 70 59 54 96 85 - La Paz 51 65 6863 162 74 56 148 61 60 56 84 79 79 76 75 58 53 71 64 62 90 82 77 57 157 52 55 81 8078 81 52 46 54 89 78 4142 51 3940 47 48 97 23 72 82 53 128 85 89 80 43 86 - Valverde 45 97 75 77 100 46 49 47 50 52 99 90 127 85 160 38 50 30 49 98 73 88 86 44 45 51 96 74 76 101 100 86 53 95 93 87 37 28 44 55 101 91 36 32 31 27 63 102 72 33 29 87 - Mirasierra 43 56 94 126 76 98 26 25 54 103 77 35 34 30 25 60 104 106 92 159 21 27 57 61 64 65 69 71 75 82 18 19 29 41 58 107 70 17 -

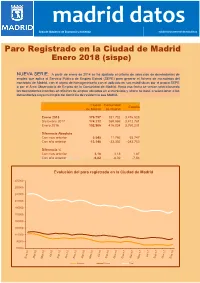

Enero 2018 (Sispe)

Área de Gobierno de Economía y Hacienda Subdirección General de Estadística Paro Registrado en la Ciudad de Madrid Enero 2018 (sispe) NUEVA SERIE: A partir de enero de 2014 se ha ajustado el criterio de selección de demandantes de empleo que aplica el Servicio Público de Empleo Estatal (SEPE) para generar el fichero de microdatos del municipio de Madrid, con el objeto de homogeneizarlo con el aplicado en sus estadísticas por el propio SEPE o por el Área Observatorio de Empleo de la Comunidad de Madrid. Hasta esa fecha se venían seleccionando los demandantes inscritos en oficinas de empleo ubicadas en el municipio y ahora se pasa a seleccionar a los demandantes cuyo municipio del domicilio de residencia sea Madrid. Ciudad Comunidad España de Madrid de Madrid Enero 2018 179.757 381.732 3.476.528 Diciembre 2017 174.212 369.966 3.412.781 Enero 2016 192.905 415.034 3.760.231 Diferencia Absoluta Con mes anterior 5.545 11.766 63.747 Con año anterior -13.148 -33.302 -283.703 Diferencia % NOTA:Con En cursivames anterior datos estimados 3,18 3,18 1,87 Con año anterior -6,82 -8,02 -7,54 Evolución del paro registrado en la Ciudad de Madrid 270000 250000 230000 210000 190000 170000 150000 130000 110000 90000 70000 Hombres Mujeres Total 0. Paro registrado por sexo y mes Parados Índice de Mes TotalHombres Mujeres feminización 60 y más 55 - 59 2017 Enero 192.905 89.761 103.144 114,9 50 - 54 Febrero 194.232 90.030 104.202 115,7 45 - 49 Marzo 191.437 88.336 103.101 116,7 Abril 186.033 85.357 100.676 117,9 40 - 44 Mayo 181.735 82.796 98.939 119,5 Junio 179.324 80.059 99.265 124,0 35 - 39 Julio 180.274 79.345 100.929 127,2 30 - 34 Agosto 182.379 80.106 102.273 127,7 Septiembre 181.859 80.458 101.401 126,0 25 - 29 Octubre 181.715 80.900 100.815 124,6 20 - 24 Noviembre 178.399 79.515 98.884 124,4 Diciembre 174.212 78.544 95.668 121,8 16 - 19 20.000 15.000 10.000 5.000 0 5.000 10.000 15.000 20.000 2018 Mujeres Hombres Enero 179.757 81.320 98.437 121,0 Paro por sexo y edad Fuente: SEPE. -

11 12 021 15 092 14 13 16

Distrito 01 - Centro 071 092 15 14 16 11 13 102 12 021 Barrios 11 - Palacio 12 - Embajadores 13 - Cortes 14 - Justicia 15 - Universidad 16 - Sol Dirección General de Estadística Distrito 01 - Centro 29 7 6 4 46 45 44 43 55 58 1 56 57 71 80 30 26 2 3 47 23 48 49 53 52 79 25 72 81 51 78 24 22 107 50 106 21 73 76 19 103 91 92 90 20 89 108 105 17 104 102 87 75 6 93 88 18 16 109 100 101 15 110 111 99 98 94 82 84 10 5 97 14 1 112 113 79 96 95 81 114 75 1 11 2 77 13 115 76 73 84 12 116 1 3 74 4 117 2 118 69 124 1 6 72 123 119 7 17 120 69 70 8 121 9 68 71 16 65 1 26 67 2 27 64 11 25 66 12 45 63 3 15 5 18 28 71 4 46 6 14 47 59 61 62 19 13 24 29 49 43 102 31 48 51 30 34 13 7 20 23 58 6 33 50 53 35 42 12 8 21 36 54 9 55 57 22 32 37 38 11 95 41 56 10 40 83 39 80 81 15 82 217 90 14 89 94 20 72 73 79 74 78 77 52 11 13 87 922122 23 24 71 67 Barrios 11 - Palacio 12 - Embajadores 13 - Cortes 14 - Justicia 15 - Universidad 16 - Sol Dirección General de Estadística Distrito 01 - Centro Barrio 11 - Palacio 15 111 99 98 97 113 a ñ a 112 14 aa¤ spp EEs 10 e dza 114 la G C zPa ío r a a R L a d l e nG a P g V r F r s a aía o R o n n m V e it ¡ 11 l e o a o s j n t 1 o 115 13 2 a 116 A ilv r r S ia Torija z ilva 84 12 a S E Cuesta de San Vni cVeicnetnete n Cuesta Sa c a la 3 rn o a B l c Jacometrezo a ió g n tu r o P n . -

Apariciones De Seres Celestiales” P

Gisela von Wobeser “II.Apariciones de seres celestiales” p. 35-52 Apariciones de seres celestiales y demoniacos en la Nueva España Gisela von Wobeser(autor) México Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas (Serie Historia Novohispana 100) Primera edición impresa: 2016 Primera edición electrónica en PDF: 2017 Primera edición electrónica en PDF con ISBN: 2019 ISBN de PDF 978-607-30-1432-8 http://ru.historicas.unam.mx Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 2019: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas. Algunos derechos reservados. Consulte los términos de uso en http://ru.historicas.unam.mx. Se autoriza la consulta, descarga y reproducción con fines académicos y no comerciales o de lucro, siempre y cuando se cite la fuente completa y su dirección electrónica. Para usos con otros fines se requiere autorización expresa de la institución. Capítulo II APARICIONES DE SERES CELESTIALES Muchos videntes suplieron sus necesidades afectivas, proyectaron sus angus- tias, requirieron protección o buscaron su sentido de la vida con figuras del más allá que los reconfortaban, consolaban en sus momentos de angustia, incertidumbre y desesperación, y los acompañaban en días especiales o sim- plemente en la cotidianidad. Por lo tanto, las historias de apariciones reflejan el mundo interior de los visionarios y manifiestan sus emociones: amor, te- mor, odio, esperanza, miedo, ternura, piedad y compasión, entre otras. Muchas monjas buscaban el vínculo con seres sobrenaturales para dar sentido a sus vidas y escapar de la soledad interior, tristeza y desesperanza que afrontaban. -

La Abolición Del Voto De Santiago En Las Cortes De Cádiz

IV. Textos 290 TEXTOS TEXTOSREVISTA DE ESTUDIOS REGIONALES Nº 64 (2002), PP. 291-308 291 La abolición del voto de Santiago en las Cortes de Cádiz José María García León Universidad de Cádiz BIBLID [0213-7525 (2002); 64; 291-308] La Constitución de 1812, en su artículo 12, especificaba que la religión de la Nación española es y será perpetuamente la católica, apostólica y romana, única verdadera. La Nación la protege por leyes sabias y justas, y prohíbe el ejercicio de cualquier otra1. Con ello se proclamaba abiertamente, y sin ningún género de du- das, el carácter confesional, católico, de nuestra Constitución doceañista. Aún así, este espíritu religioso no impidió medidas tales como el no restablecimiento de las órdenes religiosas, abolidas ya por José Bonaparte, o los artículos reguladores de la enseñanza, mostrando, pues, un claro recelo hacia la Iglesia. Esta, llamémosle, ambigüedad en materia religiosa se trocó en terminante postura en dos cuestiones que fueron objeto de intenso debate en las Cortes. De un lado, la abolición de la Inquisición, de otro, el tema que nos ocupa, esto es la supresión del llamado Voto de Santiago. 1. HACIA LA CONTRIBUCIÓN DIRECTA Como nos dice López Castellano, la idea de implantar la contribución única en España es un proyecto largamente acariciado. Ya desde el Memorial de Zabala, reinado de Felipe V, hasta el marqués de la Ensenada y Cabarrús, late un deseo de mejorar el sistema contributivo y hacerlo más justo y equitativo, a pesar de la resis- tencia de los estamentos privilegiados que, obviamente, resultaban ser los menos beneficiados de estas reformas. -

Spain | Prime Residential

Overview | Trends | Supply | Transactions | Prices Prime Residential knightfrank.com/research Research, 2020-21 Fotografía: Daniel Schafer PRIME RESIDENTIAL 2020-2021 PRIME RESIDENTIAL 2020-2021 PRIME CONTENTS RESIDENTIAL 04 OVERVIEW 08 PREMIUM HOMES FOR PREMIUM CLIENTS – SOMETHING FOR EVERY TASTE oin us as we carry out an in-depth analysis attributes that breathe life and soul into the city’s 10 J of the prime residential market, to find out trendiest neighborhoods. A STROLL THROUGH THE how COVID-19 has affected performance in this To evaluate market conditions for the city’s most CAPITAL’S TRENDIEST exclusive segment. We begin with a broad over- exclusive homes, we focused on properties valued NEIGHBOURHOODS view of the residential market as a whole, getting at over €900,000 and located in one of the city’s to grips with the latest data and venturing some main prime submarkets within the districts of projections for YE 2020 – and a few predictions Chamartín, Salamanca, Retiro, Chamberí and the for 2021. Centre. We have combed through all the latest sup- 20 Our Prime Global Forecast report paints a cheer- ply-side data, studied key indicators, like transac- OUR ANALYSIS OF THE MADRID ingly optimistic picture for the prime residential tion volume, and traced the dominant price trends PRIME MARKET market in major global cities – including Berlin, over the last four years. Paris, London and, of course, Madrid – at the close It is becoming more and more common to find of 2021. super-prime residential apartments integrated into Demand analysis has always been key to under- luxury hotels, a concept that offers owners the ulti- standing this market, and in the present circum- mate in exclusivity, comfort and privacy. -

Las Cortes De Madrid De 1457-1458 Madrid’S Cortes, 1457-1458

Las Cortes de Madrid de 1457-1458 Madrid’s Cortes, 1457-1458 Mariana MORANCHEL POCATERRA Profesora de Historia del Derecho Mexicano Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [email protected] Recibido: 2 de marzo de 2004 Aceptado: 12 de marzo de 2004 RESUMEN Publica la autora parte de las desaparecidas Cortes de Madrid de 1457-58 que se realizaron durante el reinado de Enrique IV tomando como base al Ordenamiento de Montalvo —su principal fuente de información. Asimismo, hace un cotejo con las fuentes que el propio Montalvo utilizó para redactar aquellas leyes que tienen como base a las citadas Cortes de Madrid. PALABRAS CLAVE: Cortes de Madrid 1457-1458, Enrique IV de Castilla, Ordenamiento de Montalvo. ABSTRACT The author publishes here a part of the disappeared acts from the Cortes of Madrid of 1457-58. This assembly was celebrated during the reign of Enrique IV, following Montalvo’s rule - its main source of information. It presents also a collation with the sources that the own Montalvo used to write up the acts from the mentioned Cortes of Madrid. KEY WORDS: Cortes of Madrid 1457-1458, Enrique IV of Castile, Montalvo’s rule. RÉSUMÉ L’auteur publie ici une partie des disparues actes des Courts de Madrid de 1457-58 qui se sont réunies pendant le règne d’Enrique IV en prenant comme base l’Ordonnance de Montalvo - leur principale source d’information. Il y a aussi une collation avec les sources utilisés par Montalvo lui-même pour rédiger ces lois qui ont comme base les dites Courts de Madrid. MOTS CLÉ : Courts de Madrid 1457-1458, Enrique IV de Castille, Ordonnance de Montalvo. -

BMJ Open Is Committed to Open Peer Review. As Part of This Commitment We Make the Peer Review History of Every Article We Publish Publicly Available

BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033687 on 20 August 2020. Downloaded from BMJ Open is committed to open peer review. As part of this commitment we make the peer review history of every article we publish publicly available. When an article is published we post the peer reviewers’ comments and the authors’ responses online. We also post the versions of the paper that were used during peer review. These are the versions that the peer review comments apply to. The versions of the paper that follow are the versions that were submitted during the peer review process. They are not the versions of record or the final published versions. They should not be cited or distributed as the published version of this manuscript. BMJ Open is an open access journal and the full, final, typeset and author-corrected version of record of the manuscript is available on our site with no access controls, subscription charges or pay-per-view fees (http://bmjopen.bmj.com). If you have any questions on BMJ Open’s open peer review process please email [email protected] http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ on September 29, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033687 on 20 August 2020. Downloaded from Oral versus intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency in primary care: a pragmatic, randomized, noninferiority clinical trial (OB12) ForJournal: peerBMJ Open review only Manuscript ID bmjopen-2019-033687 Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the 16-Aug-2019 Author: Complete List of Authors: Sanz Cuesta, Teresa; Comunidad de Madrid Servicio Madrileno de Salud, Gerencia Asistencial Atención Primaria. -

Hispanoamericano» Por Las Calles De Madrid

Un paseo «Hispanoamericano» por las calles de Madrid Mi primera intención al pensar en esta ponencia fue trata de hacer un paseo «real» por las calles madrileñas que recuerdan con su nombre lugares, aconte- cimientos y personajes de Hispanoamérica. Pero la extensión de la ciudad ha hecho imposible esa primera intención, porque no es habitual que esténjuntas, ni siquiera muy próximas más de dos o tres, salvo en el caso de los países o las ciudades (Parque del Retiro y Barrio de Hispanoamérica). Para redactaría he dividido el trabajo en cinco grupos distintos: 1. Países y Ciudades; 2. Conquistadores, Cronistas y Evangelizadores (en este caso nos encontraremos con nombres de personajes nacidos en la Península, pero que tuvieron una enorme importancia en los primeros momentos de la formación del Nuevo Mundo); 3. Escritores e Intelectuales; 4. Políticos; y un quinto grupo que he titulado 5. «Personajes varios», en el que encontraremos una serie de nombres queno son fácilesde incluir en ninguno de losapartados anteriores, pero que, sin embargo, ponen también de manifiesto esa presencia del Nuevo Continente en lacapital de España. Y, aun cuando la nómina de vías madrileñas dedicadas a Hispanoamérica es muy extensa, no vamos a verlas todas. Me he visto obligada aescogersólo unospocosnombres de cada grupo porque el tiempo de exposición es limitado y no sería correcto extenderse más allá de lo que se ha establecido. La historia de Hispanoamérica y sucultura están vivas en este Madrid y ésto es lo que quiero poner de manifiesto: que podemos repasaría dando un vistazo rápido al callejero. Anales de literatura hispanoamericana, núm. -

Los Historiadores De Hispanoamérica Generalmente Estudian Su Re Gión Como Si Las Trece Colonias Inglesas O La Nueva Francia Nunca Hubiesen Existido

La nación en ausencia: primeras formas de representación en México José Antonio Aguilar Rivera* Los historiadores de Hispanoamérica generalmente estudian su re gión como si las Trece Colonias inglesas o la Nueva Francia nunca hubiesen existido. Uno de los principales problemas de esa historiogra fía es su aislamiento intelectual. Después de todo,como afirma Anthony Pagden (1994, x), América comenzó como un transplante de Europa en el Nuevo Mundo: la historia intelectual de su desarrollo temprano es una historia de transmisión y reinterpretación, una historia sobre cómo argumentos europeos tradicionales de los textos clásicos fueron adaptados para enfrentar los retos de circunstancias nuevas e imprevistas. La perspectiva comparada arroja luz sobre algunas singularidades de Hispanoamérica. Esta estrategia revela un plano más vasto en el cual la América española ocupa un lugar especíñco en la experiencia atlántica (véase Hale, 1973). En contra de lo que comúnmente se piensa, los hispanoamericanos fundadores de las nuevas naciones no sólo repitieron y copiaron argumentos europeos (Véliz, 1994). Las diferentes condiciones históricas moldearon el pensamiento político de formas originales.' Aquí se estudian las primeras formas de repre- * Investigador de lo División de Esluilins Polítieos, cide. El autor dosca agradecer la colabornclón de Ceciliu MnrUnuz Gallardo y Sergio Emilio Sdenx. Los comontarloa y sugerencias de Rnfnel Rujas fueron de gran utilidad. Este artículo fue recibido en diciembre de 1997 y fue revisado en junio de 1988. 'Para uiu buena revisión general de la historia de las ideas en este período véase SaCTord, 1995. Política y Gobierno, vol. V, núm. 2,segundo semestre de 1998 423 José Antonio Aguilar Rivera sentación política en México a principios del siglo xix.