The Politics of the Aesthetic in the Southern Cone By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

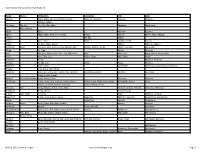

Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First Name Surname

To find your name, click 'ctrl' + 'F' and type your surname. If you entered after 20/02/20 you will not appear on this list, an updated version will be put online on or around the 28/02/20. Runners cannot move into an earlier wave, but you are welcome to move back to a later wave. You do NOT need to inform us of your decision to do this. If you have any problems, please get in touch by phoning 01522 699950. COLOUR RACE APPROX TO THE START WAVE NO. START TIME 1 BLUE A 09:10 2 RED A 09:10 3 PINK A 09:15 4 GREEN A 09:20 5 BLUE B 09:32 6 RED B 09:36 7 PINK B 09:40 8 GREEN B 09:44 9 BLUE C 09:48 10 RED C 09:52 11 PINK C 09:56 12 GREEN C 10:00 VIP BLACK Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First name Surname 11 Pink 1889 Rebecca Aarons Any Black 1890 Jakob Abada 2 Red 4 Susannah Abayomi 3 Pink 1891 Yassen Abbas 6 Red 1892 Nick Abbey 10 Red 1823 Hannah Abblitt 10 Red 1893 Clare Abbott 4 Green 1894 Jon Abbott 8 Green 1895 Jonny Abbott 12 Green 11043 Pamela Abbott 6 Red 11044 Rebecca Abbott 11 Pink 1896 Leanne Abbott-Jones 9 Blue 1897 Emilie Abby Any Black 1898 Jennifer Abecina 6 Red 1899 Philip Abel 7 Pink 1900 Jon Abell 10 Red 600 Kirsty Aberdein 6 Red 11045 Andrew Abery Any Black 1901 Erwann ABIVEN 11 Pink 1902 marie joan ablat 8 Green 1903 Teresa Ablewhite 9 Blue 1904 Ahid Abood 6 Red 1905 Alvin Abraham 9 Blue 1906 Deborah Abraham 6 Red 1907 Sophie Abraham 1 Blue 11046 Mitchell Abrams 4 Green 1908 David Abreu 11 Pink 11047 Kathleen Abuda 10 Red 11048 Annalisa Accascina 4 Green 1909 Luis Acedo 10 Red 11049 Vikas Acharya 11 Pink 11050 Catriona Ackermann -

Retriever (Labrador)

Health - DNA Test Report: DNA - HNPK Gundog - Retriever (Labrador) Dog Name Reg No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Test Result A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S EL TORO AT AV0901389 27/08/2017 Dog BLACKSUGAR LUIS WATERLINE'S SELLERIA 27/11/2018 Clear BALLADOOLE (IMP DEU) (ATCAQ02385BEL) A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S GET LUCKY (IMP AV0904592 09/04/2018 Dog CLEARCREEK BONAVENTURE A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S TEA FOR 27/11/2018 Clear DEU) WINDSOCK TWO (IMP DEU) AALINCARREY PUMPKIN AT LADROW AT04277704 30/10/2016 Bitch MATTAND EXODUS AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE 20/11/2018 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE AR03425707 19/08/2014 Bitch BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 27/08/2019 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER MAGIC AR03425706 19/08/2014 Dog BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 23/08/2017 Clear AALINCARREY WISPA AT01657504 09/04/2016 Bitch AALINCARREY MANNANAN AFINMORE AIRS AND GRACES 03/03/2020 Clear AARDVAR WINCHESTER AH02202701 09/05/2007 Dog AMBERSTOPE BLUE MOON TISSALIAN GIGI 12/09/2016 Clear AARDVAR WOODWARD AR03033605 25/08/2014 Dog AMBERSTOPE REBEL YELL CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 29/11/2016 Carrier AARDVAR ZOLI AU00841405 31/01/2017 Bitch AARDVAR WINCHESTER CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 12/04/2017 Clear ABBEYSTEAD GLAMOUR AT TANRONENS AW03454808 20/08/2019 Bitch GLOBETROTTER LAB'S VALLEY AT ABBEYSTEAD HOPE 25/02/2021 Clear BRIGBURN (IMP SVK) ABBEYSTEAD HORATIO OF HASELORHILL AU01380005 07/03/2017 Dog ROCHEBY HORN BLOWER HASELORHILL ENCORE 05/12/2019 Clear ABBEYSTEAD PAGEANT AT RUMHILL AV01630402 10/04/2018 Dog PARADOCS BELLWETHER HEATH HASELORHILL ENCORE -

Oregon Obituaries II

Oregon Obituaries II GFO Members may view this collection in MemberSpace > Digital Collections > Indexed Images > Oregon Obituaries II. Non-members may order a copy at GFO.org > Resources > Indexes > All Indexes > Oregon Obituaries II Newspaper Newspaper Surname Given Name Article Type Comments Scan # Article Date Title City Aaben Alide Funeral notice Aaben Alide 1992 1992 (NG) (NG) Aamodt Edwin D Obituary Clarke M4 (7) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Aasby Jerry G Obituary Clarke M4 (19) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Abacherli Zeno Anton Obituary Clarke M4 (6) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Abell Rowena Marie Obituary Clarke M4 (12) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Absten Leila Heinz Obituary Clarke M4 (17) 1990 Statesman Journal Salem Absten Margaret Middleton Obituary Clarke M4 (9) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Acevedo Pedro Vasquez Obituary Acevedo Pedro 1999 1999 (NG) (NG) Ackerson Jean L Obituary Clarke M4 (14) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Adair Laverne Obituary Clarke M4 (18) 1996 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Anna G Obituary Clarke M4 (4) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Beatrice M Obituary Adams Beatrice 1992 1992 (NG) (NG) Adams Daisy Irene Obituary Clarke M4 (7) 1996 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Edward Obituary Clarke M4 (1) 1994 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Ella Lee Obituary Clarke M4 (4) 1995 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Gladys Obituary Clarke M4 (11) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Joseph Z Obituary Adams Joseph 1993 1993 (NG) (NG) Adams Joyce Elaine Obituary Clarke M4 (10) 1993 Statesman Journal Salem Adams Juanita V Obituary -

Samuel Milner

153: Samuel Milner Basic Information [as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC] Name as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC: S. Milner Rank: Private Battalion / Regiment: 11th Bn. Cheshire Regiment Service Number: 49532 Date of Death: 08 January 1920 Age at Death: ? Buried / Commemorated at: St Mary & St Helen Churchyard, Neston Additional information given by CWGC: None Samuel Milner was (probably) the seventh, child of Parkgate fisherman William and Charlotte Milner. William married Charlotte Roberts, a daughter of Leighton labourer Charles and Ann Roberts, at Our Lady & St Nicholas & St Anne, the Liverpool Parish Church, in April/June 1878 and George, their first child, was born in early 1879. It is believed another male child (unnamed) was born in early 1881 and was buried a few days later. Samuel was born in late 1891 and he was baptised at Neston Parish Church on 20 November 1891. By the time of the 1901 census the couple had eight surviving children although Gertrude died very soon after the census date: 1901 census (extract) – Parkgate William Milner 43 fisherman born Ness Holt Charlotte 41 born Parkgate William 18 fisherman born Parkgate George 22 platelayer born Neston Polly M. 17 servant born Parkgate Sarah A. 14 servant born Parkgate Margarite 12 born Parkgate Samuel 10 born Parkgate Gertrude 1 month born Parkgate Lottie 6 born Parkgate The known children of William and Charlotte are: Page | 1627 George registered early 1879 but no record of baptism at Neston. George married Mary Banks at St Peter’s Church, Heswall, in April / June 1906 and in 1911 (32, general labourer) he was living at Pear Tree Cottage, Heswall with Mary (30, laundress, born Heswall) and daughter Edith (3, born Heswall). -

Aristotelian Rhetoric in Homer

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1959 Aristotelian Rhetoric in Homer Howard Bernard Schapker Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Schapker, Howard Bernard, "Aristotelian Rhetoric in Homer" (1959). Master's Theses. 1693. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/1693 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1959 Howard Bernard Schapker ARISTOTELIAN R1mfDRIC IN RlMIR by Howard B. So.plc.... , 5.J. A Th•• le S._ltt.ad In Partial , .. lIIIMnt. of t~ ~lr.-.n'. tor the 0.0'•• of Mas'er 01 Art. Juna 19$9 LIFE Howard B.rnard Schapker was born In Clnclnnat.I, Ohio. Febru ary 26, 1931. He attended St.. Cathe,lne aral&llnr School, Clnclnnat.i, trom 1931 to 1945 and St. xavIer Hlgb School, tbe .... cU.y, troll 1945 to 1949. Fr•• 1949 to 19S.3 be attend" xavier University, Clncln.. natl. In Jun., 19S3. h. va. graduat." troll xavier University vltll the degr•• of Bachelor ot Art.. on A.O.' S, 1953, he ent..red the Soclet.y of J •• us at Miltord, Oblo. The autbor Mgan his graduate .tucU.. at Loyola Un lve.. a 1 toy. Cblcago, In september, 19S5. -

Christian Names for Catholic Boys and Girls

CHRISTIAN NAMES FOR CATHOLIC BOYS AND GIRLS CHRISTIAN NAMES FOR CATHOLIC BOYS AND GIRLS The moment has arrived to choose a Christian name for the baptism of a baby boys or girl. What should the child be called? Must he/she receive the name of a saint? According to the revised Catholic Church Canon Law, it is no longer mandatory that the child receive the name of a saint. The Canon Law states: "Parents, sponsors and parish priests are to take care that a name is not given which is foreign to Christian sentiment." [Canon # 855] In other words, the chosen name must appeal to the Christian community. While the names of Jesus and Judas are Biblical in nature, the choice of such names would result in controversy. To many, the Name Jesus is Sacred and the Most Holy of all names. Because Judas is the disciple who betrayed Jesus, many feel this would be a poor choice. Equally, names such as 'cadillac' or 'buick' are not suitable because they represent the individual person's personal interest in certain cars. The following is a short list of names that are suitable for boys and girls. Please keep in mind that this list is far from complete. NAMES FOR BOYS Aaron (Heb., the exalted one) Arthur (Celt., supreme ruler) Abel (Heb., breath) Athanasius (Gr., immortal) Abner (Heb., father of light) Aubrey (Fr., ruler) Abraham (Heb., father of a multitude) Augustine (Dim., of Augustus) Adalbert (Teut., nobly bright) Augustus (Lat., majestic) Adam (Heb., the one made; human Austin (Var., of Augustine) being; red earth) Adelbert (Var., of Adalbert) Baldwin (Teut., noble friend) Adrian (Lat., dark) Barnabas (Heb., son of consolation) Aidan (Celt., fire) Barnaby (Var., of Bernard) Alan (Celt., cheerful) Bartholomew (Heb., son of Tolmai) Alban (Lat., white) Basil (Gr., royal) Albert (Teut., illustrious) Becket (From St. -

Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel Huber David Jaramillo Gil The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3862 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] QUEER BAROQUE: SARDUY, PERLONGHER, LEMEBEL by HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 HUBER DAVID JARAMILLO GIL All Rights Reserved ii Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Carlos Riobó Chair of Examining Committee Date Carlos Riobó Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paul Julian Smith Magdalena Perkowska THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Queer Baroque: Sarduy, Perlongher, Lemebel by Huber David Jaramillo Gil Advisor: Carlos Riobó Abstract: This dissertation analyzes the ways in which queer and trans people have been understood through verbal and visual baroque forms of representation in the social and cultural imaginary of Latin America, despite the various structural forces that have attempted to make them invisible and exclude them from the national narrative. -

Major Bowes Amateur Magazine 3403.Pdf

T HE MAGAZINE OF TWENTY MILLION LISTENERS MAGAZINE MARCH 25 CENTS T HIS ISS U E AMATEUR S IN PICTURES AND STORY HAMBURGER MARY THE YOUMAN BROS. DIAMOND·TOOTH MARY PE~RY THE GARBAGE TENOR SARA BERNER DORIS WESTER VERONICA MIMOSA BU$·BOY DUNNE WYOMING JACK O'BRIEN AND- FIFTY OTHERS • SUCCESS STORIES lilY PONS DAVID SARNOFF ROSA PONSELLE EDWIN C. HILL AMELIA EARHART LAWRENCE TIBBETT FRED A5TAIRE GR .... YAM McNAMEE AND OTHERS • SPECIAL FEATURES MAJOR BOWES-HIS STORY GENE DENNIS WOMEN'S EXCLUSIVE FASHIONS •• •• AND MEN'S YOUR LOOKING GLASS LOWDOWN ON BROADWAy •••• AND HOllYWOOD NIGHT AT THE STUDIO AMATEURS' HALL OF FAME LOOKING BACKWARD FAMOUS AMATEURS OF HISTORY PICTURE TABLOID AND OTHER FEATURES REVOLUTIONARY! ACTUALLY WIPES WINDSHIELDS o C leans Because It Drains! I - I (' I ' I "~ the fil '~ 1 I'crd .I1'",>I" I'IIICIlI in \l indshid.1 wi pe r ], I:u/, ·.. - a n; \"olul iUllan" " vl1 slrut:! iUII I h at kee ps windshields .. Ie,OWI' a 11.1 .h-i(' I'. TIle Uc,, -Hidc il la.l c cO lisish of a Iw l· low. I'l'dol"alc .1 tulle o f Foft. carlWII·lJasc rll],l,c r, SC i ill " slwf, of stain ic;;;; iilcel. A~ l ilt, blade sweep! OI cross the g la ~s . .. h c nHlt,· ,II','as of I" "C:", III"O .lIul \'a CIIIIII1 arc c rca tcII, fore· ill ;': wal(" ," throll;.: h Ihe holl's aTH I COII ,,- talltir cl c allil1~ the w i!,i!! ;! ,"ill,;. .1 \ IIlIltilly w ilillshie hi w-ill I, c cleallctl lillII'll ra ~l l'I" . -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abrev Nicknames

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abrev Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abby, Abbie, Ab, Gail, Nabby, Gubby, Deborah, Gobinet Gobnait Gobnata Gubbie, Debbie Abraham Ab, Abr, Ab, Abr, Abe, Abby Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abram Adam Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Aggie, Aggy, Assie, Inez, Nessa Nancy Aigneis Agnus, Agna, Agneta Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Lena Eileen Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Al, Bert, Albie, Bertie Ailbhe Albertus, Alberti Alexander Alexr Ala, Alec, Alex, Andi, Ec, Lex, Xandra, Ales Alistair, Alaster, Sandy Alastar, Saunder Alexander Alfred Al, Fred Ailfrid Alfredus Alice Eily, Alcy, Alicia, Allie, Elsie, Lisa, Ally, Alica Ellen Ailis, Eilish Alicia, Alecia, Alesia, Alitia Alicia Allie, Elsie, Lisa Alisha, Elisha Ailis, Ailise Alicia Allowshis Allow Aloysius, Aloyisius Aloysius Al, Ally, Lou Lewis Alaois Aloysius Ambrose Brose, Amy Anmchadh Ambrosius, Anmchadus, Animosus Amelia Amy, Emily, Mel, Millie Anastasia Anty, Ana, Stacy, Ant, Statia, Stais, Anstice, Anastatia, Anstace Annstas Anastasia Stasia, Ansty, Stacey Andrew And,Andw,Andrw Andy, Ansey, Drew Aindreas Andreas Ann/Anne Annie, Anna, Ana, Hannah, Hanna, Hana, Nancy, Nany, Nana, Nan, Nanny, Nainseadh, Neans Anna Hanah, Hanorah, Nannie, Susanna Nance, Nanno, Nano Anthony Ant Tony, Antony, Anton, Anto, Anty Anntoin, Antoin, Antoine Antonius, Antonious Archibald Archy, Archie Giolla Easpuig Arthur Artr, Arthr Art, Arty Artur Arcturus, Arturus Augustine Austin, Gus, Gustus, Gussy Augustus Aibhistin, Aguistin Augustinus, Augustinius Austin -

Marriage Certificates

GROOM LAST NAME GROOM FIRST NAME BRIDE LAST NAME BRIDE FIRST NAME DATE PLACE Abbott Calvin Smerdon Dalkey Irene Mae Davies 8/22/1926 Batavia Abbott George William Winslow Genevieve M. 4/6/1920Alabama Abbotte Consalato Debale Angeline 10/01/192 Batavia Abell John P. Gilfillaus(?) Eleanor Rose 6/4/1928South Byron Abrahamson Henry Paul Fullerton Juanita Blanche 10/1/1931 Batavia Abrams Albert Skye Berusha 4/17/1916Akron, Erie Co. Acheson Harry Queal Margaret Laura 7/21/1933Batavia Acheson Herbert Robert Mcarthy Lydia Elizabeth 8/22/1934 Batavia Acker Clarence Merton Lathrop Fannie Irene 3/23/1929East Bethany Acker George Joseph Fulbrook Dorothy Elizabeth 5/4/1935 Batavia Ackerman Charles Marshall Brumsted Isabel Sara 9/7/1917 Batavia Ackerson Elmer Schwartz Elizabeth M. 2/26/1908Le Roy Ackerson Glen D. Mills Marjorie E. 02/06/1913 Oakfield Ackerson Raymond George Sherman Eleanora E. Amelia 10/25/1927 Batavia Ackert Daniel H. Fisher Catherine M. 08/08/1916 Oakfield Ackley Irving Amos Reid Elizabeth Helen 03/17/1926 Le Roy Acquisto Paul V. Happ Elsie L. 8/27/1925Niagara Falls, Niagara Co. Acton Robert Edward Derr Faith Emma 6/14/1913Brockport, Monroe Co. Adamowicz Ian Kizewicz Joseta 5/14/1917Batavia Adams Charles F. Morton Blanche C. 4/30/1908Le Roy Adams Edward Vice Jane 4/20/1908Batavia Adams Edward Albert Considine Mary 4/6/1920Batavia Adams Elmer Burrows Elsie M. 6/6/1911East Pembroke Adams Frank Leslie Miller Myrtle M. 02/22/1922 Brockport, Monroe Co. Adams George Lester Rebman Florence Evelyn 10/21/1926 Corfu Adams John Benjamin Ford Ada Edith 5/19/1920Batavia Adams Joseph Lawrence Fulton Mary Isabel 5/21/1927Batavia Adams Lawrence Leonard Boyd Amy Lillian 03/02/1918 Le Roy Adams Newton B. -

Masculine Textualities: Gender and Neoliberalism in Contemporary Latin American Fiction

MASCULINE TEXTUALITIES: GENDER AND NEOLIBERALISM IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN FICTION Vinodh Venkatesh A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (Spanish). Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Oswaldo Estrada, Ph.D. María DeGuzmán, Ph.D. Irene Gómez-Castellano, Ph.D. Juan Carlos González-Espitia, Ph.D. Alfredo J. Sosa-Velasco, Ph.D. © 2011 Vinodh Venkatesh ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT VINODH VENKATESH: Masculine Textualities: Gender and Neoliberalism in Contemporary Latin American Fiction (Under the direction of Oswaldo Estrada) A casual look at contemporary Latin American fiction, and its accompanying body of criticism, evidences several themes and fields that are unifying in their need to unearth a continental phenomenology of identity. These processes, in turn, hinge on several points of construction or identification, with the most notable being gender in its plural expressions. Throughout the 20th century issues of race, class, and language have come to be discussed, as authors and critics have demonstrated a consciousness of the past and its impact on the present and the future, yet it is clear that gender holds a particularly poignant position in this debate of identity, reflective of its autonomy from the age of conquest. The following pages problematize the writing of the male body and the social constructs of gender in the face of globalization and neoliberal policies in contemporary Latin American fiction. Working from theoretical platforms established by Raewyn Connell, Ilan Stavans, and others, my analysis embarks on a reading of masculinities in narrative texts that mingle questions of nation, identity and the gendered body. -

Unapologetic Queer Sexualities in Mexican and Latinx Melodrama

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sácala (del closet): Unapologetic Queer Sexualities in Mexican and Latinx Melodrama A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Spanish by Oscar Rivera September 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Freya Schiwy, Co-Chairperson Dr. Ivan E. Aguirre Darancou, Co-Chairperson Dr. Alessandro Fornazzari Dr. Richard T. Rodriguez Copyright by Oscar Rivera 2020 The Dissertation of Oscar Rivera is approved: Co-Chairperson Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements First and for most, I thank the inmenso apoyo granted by Dr. Freya Schiwy who allowed and stimulated my pursuit of jotería when I, naively, was afraid/embarrassed to engage with explicit sexuality in an academic setting. Her continuous supportive embrace, availability, constant chats that extended beyond office hours and gracious patience has made my career at the University of California, Riverside an unforgettable and marvelous experience. I will forever be indebted to her por cambiar mi mundo by teaching myself (and cohort) to question everything we took for granted. I would like to thank my other professors who have profoundly shaped my knowledge and allowed my queer readings and essays in their classes even when that was not part of their syllabus, for it permitted a remarkable growth opportunity on my part: Dr. Marta Hernández- Salván for her always-challenging classes; Dr. Alessandro Fornazzari for his reassurance and recommendation of Pedro Lemebel (the inspiration of my dissertation); I am also eternally grateful for Dr. Iván E. Aguirre Darancou for his patience in reading several versions of my chapters and the excellent reading recommendations; Dr.