Ag Notes Von Thum.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wind of Doctrine Threshing and Winnowing

Wind of Doctrine Threshing and Winnowing PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 25 Aug 2010 17:06:53 UTC Contents Articles Threshing 1 Winnowing 2 Threshing floor 4 Chaff 4 Harvest 6 Wheat 7 Epiphany (feeling) 23 References Article Sources and Contributors 25 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 26 Article Licenses License 27 Threshing 1 Threshing Threshing is the process of loosening the edible part of cereal grain (or other crop) from the scaly, inedible chaff that surrounds it. It is the step in grain preparation after harvesting and before winnowing, which separates the loosened chaff from the grain. Threshing does not remove the bran from the grain. Threshing may be done by beating the grain using a flail on a threshing floor. Another traditional method of threshing is to make donkeys or An animal powered thresher oxen walk in circles on the grain on a hard surface. A modern version of this in some areas is to spread the grain on the surface of a country road so the grain may be threshed by the wheels of passing vehicles. However, in developed areas it is now mostly done by machine, usually by a combine harvester, which harvests, threshes, and winnows the grain while it is still in the field. The cereal may be stored in a threshing barn. A Threshing Bee is a festival held in communities to commemorate this process. The event is often held over multiple days and includes flea markets, activity booths, hog wrestling and dances. -

Cass City H Onicl, E

CASS CITY H ONICL, E. ..... ~o~ ,: -, Vol. 14, No. 6. CASS CITY, MICH.; FRIDAY, JUNE 7, 1918 ..... 8 PAGES l I ' l II llll I M ' l'!'l : 'i I '- "l'~l ' r ,, .... - , '~ ~ ., , . ~ ..~ W. S. DN[ ! Y" ~" A. ELyCT___OFFICERS.S '~flT II IN~r~ NHrN " plying ~omforts and delicacies to men tUliRiViril |ivrK tlinger long in their memories. ,,~,,,m,,,,L,~ v,,~,, ] ,'When will the war end? That's a [ "e andS:Lyre rtoepfgen Brought EFFOT'R the '~business meeting of the Y. mnt,mmmnr nm, n|nln[hard:'q uesti°n. If it depends on man ,P. A. held at the home of Miss Grace N[XTDDU)IIY I Meiser on Tuesday evening, the fol- IiiigflNi:F iiN Pfl~iNIpower it may be two or three years T°ge~her~by Lost Aviator" gl[J|~||~. U|| |~i|D~[bef0re the allies will be victorious. [IN DECORATIONDAYI , [lowifig officers were elected for the "' "~f ~he e~d ma~" come in si~ weeks ,en~uin~= six months: President, Alma Mark. trove been, ~IOOKIIIg '* for a fev ........oi.lA blOll" ~L. and Mrs. P. A. Koepfgen of Cass TUSCOLA COUNTY'S QUOTA HAS Vice President, Roy Striffier. W:. GORDON HIN~S, BACK FROM in Germany and Austria. I saw Ger- CLOUDS FAIL TO DARKEN THE City, had a happy meeting in France recentT~f ~~B0th ~young ~eh~are in the~:~ ~EEN INCRF~SED TO , ~Secretary, Stanley:Striffler. : :;;FRANCE,.GIVES HIS, OPINION man.) l?riso~rs, on .Apl~l. 9 who ~wp:re sPIRIT 0F PATRIOTISM ~. bdgs¢'~round their feet~{~ place of aviation service but in different com- " $557,380. -

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES in the HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters a Dissertation Submitted to the Johns Hopkins Universit

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES IN THE HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2013 © 2013 Jaime L. Waters All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Vital to an agrarian community’s survival, threshing floors are agricultural spaces where crops are threshed and winnowed. As an agrarian society, ancient Israel used threshing floors to perform these necessary activities of food processing, but the Hebrew Bible includes very few references to these actions happening on threshing floors. Instead, several cultic activities including mourning rites, divination rituals, cultic processions, and sacrifices occur on these agricultural spaces. Moreover, the Solomonic temple was built on a threshing floor. Though seemingly ordinary agricultural spaces, the Hebrew Bible situates a variety of extraordinary cultic activities on these locations. In examining references to threshing floors in the Hebrew Bible, this dissertation will show that these agricultural spaces are also sacred spaces connected to Yahweh. Three chapters will explore different aspects of this connection. Divine control of threshing floors will be demonstrated as Yahweh exhibits power to curse, bless, and save threshing floors from foreign attacks. Accessibility and divine manifestation of Yahweh will be demonstrated in passages that narrate cultic activities on threshing floors. Cultic laws will reveal the links between threshing floors, divine offerings and blessings. One chapter will also address the sociological features of threshing floors with particular attention given to the social actors involved in cultic activities and temple construction. By studying references to threshing floors as a collection, a research project that has not been done previously, the close relationship between threshing floors and the divine will be visible, and a more nuanced understanding of these spaces will be achieved. -

CARPETS! New Gas Stove

SHADOWED FOR WEEKS. JACK, THE BOY MISSIONARY. AN INTERESTING CLOCK. Ttu-eshiuc In Syria. QEMI-ANNUAL REPORT of the SILK FROM THE SPIDER. On the outskirts of each village ia a O.ToHNSTOWN SAVINGS BANK, May 31, A Baby Who Survived the Peril, of Cen- Its Maker Is Proud of It,but He lias No level space of ground of sufficient Bize to 1 HBO. A tral to at Lut In Wish to Make Another. assiw. Book Market LITERARY MAN'S PECULIAR EXPERI- Africa IJlo London. answer the requirements of the village value. value. DIFFICULTIES IN THE WAV OF PRO- a on estate.... $ ENCE A tablet to the memory of Little Jack, In the window of German jeweler which is known the name Loans real e#3 $ 375,739 9.1 DURING HIS VACATION.. by of the ba- cash la hunks .. as was called, DUCING QUANTITIES. on street, SR.S/5 90 337.575 no | the boy missionary, he Court Brooklyn, there stands yader, or threshing floor. Each farmer Cash on hand J4.4HS M 14 fSH 34 children, erected by Sunday school was a brass clock not more than ten inches and peasant has his own particular por- U. S. 4-per-cont. boons., lmt.ooo on J40.7W) 00 Bo Hud Committed No Crime, but n De- unveiled over Ids grave in Loudon. Lit- Johnstown water Co. The Method of Englishman Named high. Tho passerby who looks through tion marked off by a row of stones, and bonds..... 1ir.,00000 115,000 00 tective Followed 11 iin All Around?He tle was an Westmoreland Jack only 7 years old when he the window sees under the clock, which this portion is religiously handed down A Cam- | Didn't Know of It Until Four Years died. -

Spanish Agriculture: the Long Siesta, 1765-1965 Is the First Major Study in English of Spanish Agrarian History

Spanish agriculture: the long Siesta, 1765-1965 is the first major study in English of Spanish agrarian history. James Simpson examines how traditional agriculture responded to population growth and the inte gration of commodity markets, emphasising both Spain's regional vari ations and its context in Europe. Simpson argues that decisive changes in farming techniques only occurred at the Start of this century~ leading n:!~i~~.2~J>.r:~dll_c~Vityand the start or,~~fl:I!lll~~og!;!LP~J.?l': ment ~_S)11!~!:£llJ>.!.~ULm_L~9l0~~d 1940~~_~n1~"E~"suming in the .• ~ 19508. He rejects arguments that slow giowtI1can be eJg?laiu!!ifTiY:tmor fes-OUJ:~~S or ineffiCIent farmers .. Indeed, farmerS were" quick to change when they had market opportunities (as was the case with olive oil, oranges and rice). By contrast, change was slower in those areas such as cereals where traditional technologies remained profitable. Simpson concludes that there were strict limits on absorbing labour in Spain's dry lands, and labour was retained in agriculture because of govern ment policies. Cambridge Studies in Modern Economic History 2 Spanish agriculture: the long Siesta, 1765-1965 Cambridge Studies in Modern Economic History Spanish agriculture: Series editors the long Siesta, Charles Feinstein 1 6 All Souls College, Oxford 1765- 9 5 Patrick O'Brien James Simpson The Institute of Historical Research, London Universidad Carlos III de Madrid Barry Supple The Leverhulme Trust Peter Temin Massachusetts Institute of Technology Gianni Toniolo Universita degli Studi di Venezia Cambridge Studies in Modern Economic History is a major n~ initiative in economic history publishing, and a flagship series f Cambridge University Press in an area of scholarly activity in whi, it has long been active. -

The Losses in the Rice Harvest Process: a Review

sustainability Review The Losses in the Rice Harvest Process: A Review Xue Qu 1,*, Daizo Kojima 1, Laping Wu 2 and Mitsuyoshi Ando 1 1 Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan; [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (M.A.) 2 College of Economics and Management, China Agricultural University, 17 Qinghua East Road, Haidian District, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: We review existing studies on rice harvest loss from the aspects of estimation methods, magnitudes, causes, effects, and interventions. The harvest losses examined occurred from the field reaping to storage processes, including threshing, winnowing, and field transportation. We find that existing studies on rice harvest losses have focused on quantitative losses in Asia and Africa. Lack of knowledge, inadequate harvesting techniques, poor infrastructure, and inefficient harvest management practices are considered critical contributors to the losses. The magnitudes and causes of rice harvest losses are now better understood than interventions, which have simply been presented but lack an assessment of the effects and a cost–benefit analysis. Interestingly, reduction in harvest losses may threaten some farmers’ profits, such as rural women who make their living from post-production manual operations. Considering the current status of the literature, future researchers should examine how to balance social and individual welfare since farmers are key stakeholders in intervention implementation. A good understanding of the existing researches can help clarify future efforts for loss reduction, thereby reducing the burden of increasing agricultural production and promoting sustainable development of resources and the environment. -

Five Continents

eCONTI by N.L Vavilov Finally published in English, this book contains descriptions by Academician NI. Vavilov ofthe expeditions he made between 1916 and 1940 to jive continents, in search ofnew agricultural plants and conjil1nation ofhis theories on plant genetic divmity. Vavilov is ironic, mischievolls, perceptive, hilariolls and above all scholarly. This book is a readable testament to his tenacity and beliefin his work, in the foee ofthe greatest adversity. 11 This book is dedicated fa the memory of Nicolay Ivanovich Vavilov (1887-1943) on the IIOth anniversary of his birth 11 N.!. Vavilov Research Institure of Plant Industry • International Plant Genetic Resources Institute United States Agency for International Development • American Association for the Advancement of Science United States Depanment ofAgriculture • Agricultural Research Service • National Agricultural Library • THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF N/COLAY IVANOVICH VAVILOV (1887-1943) ON THE 11 Oth ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH • • FIVE CONTINENTS NICOLAY IVANOVICH VAVILOV Academy ofSciences, USSR Chemical Technological and Biological Sciences Editor-in-chief L.E. ROOIN Tramkzted ft-om the Russian by OORIS LOVE Edited by SEMYON REZNIK and PAUL STAPLETON 1997 • The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI) is an autonomous international scientific organization operating under the aegis of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The international status of IPGRI is conferred under an Establishment Agreement signed by the Governments ofAustralia, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Congo, COSta Rica, Cote d'Ivoire, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Malaysia, Mauritania. Morocco, Pa!cisran, Panama, Peru, Poland, Porrugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Sloval, Republic, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and the Ukraine. -

Chasing the Traces of Diffusion of Agriculture During the Early Neolithic in the Western Mediterranean Coast

CHASING THE TRACES OF DIFFUSION OF AGRICULTURE DURING THE EARLY NEOLITHIC IN THE WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN COAST Ferran Antolín*, Ramon Buxó** Abstract: The knowledge on the diffusion of agriculture during the Early Neolithic in the Western Mediterranean is still sparse. This paper reviews the available information and presents some recent results that bring out the potential of ar - chaeobotanical materials on this topic. Crop exchange and diffusion in the western Mediterranean basin is observed but differences between the so-called Impressed ware and the Cardial ware cultures are still difficult to state. Possible exchanges between the LBK-II and Cardial ware cultures are evaluated. Agricultural practices are still hard to compare on a site-to- site basis but some regional patterns are presented. Keywords: prehistoric agriculture, process of neolithisation, diffusion of agriculture, archaeobotany, Western Mediterranean. Resumen: El conocimiento del proceso de difusión de la agricultura en el neolítico antiguo del Mediterráneo occidental es toda - vía escaso. En este trabajo se revisa la información disponible y se presentan los nuevos resultados que muestran el potencial del material arqueobotánico en este tema. El intercambio de cultivos y su difusión en el oeste del Mediterráneo es constatado pero las diferencias entre las llamadas cultura Impresa y la cultura Cardial son todavía difíciles de demostrar. Posibles intercambios entre el LBK-II y la cultura cardial son evaluados. Las prácticas agrícolas todavía son difíciles de comparar de un sitio a otro pero al - gunos patrones regionales son presentados. Palabras clave: agricultura prehistórica, proceso de neolitización, difusión de la agricultura, arqueobotánica, Mediterráneo oc - cidental. Introduction The western Mediterranean is a well-defined territory For instance, some areas lack of new systematic (pub - between the western Italian coast, the eastern coast of lished) investigations, such as the Gulf of Lyon, south - the Iberian Peninsula and the northern coast of Mo - ern Italy or northern Africa. -

Anna, Grandmother of Jesus: a Message of Wisdom and Love

First published and distributed in the United Kingdom by: Hay House UK Ltd, Astley House, 33 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JQ Tel: +44 (0)20 3675 2450; Fax: +44 (0)20 3675 2451; www.hayhouse.co.uk Published and distributed in the United States of America by: Hay House Inc., PO Box 5100, Carlsbad, CA 92018-5100 Tel: (1) 760 431 7695 or (800) 654 5126; Fax: (1) 760 431 6948 or (800) 650 5115 www.hayhouse.com Published and distributed in Australia by: Hay House Australia Ltd, 18/36 Ralph St, Alexandria NSW 2015 Tel: (61) 2 9669 4299; Fax: (61) 2 9669 4144 www.hayhouse.com.au Published and distributed in the Republic of South Africa by: Hay House SA (Pty) Ltd, PO Box 990, Witkoppen 2068 [email protected]; www.hayhouse.co.za Published and distributed in India by: Hay House Publishers India, Muskaan Complex, Plot No.3, B-2, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi 110 070 Tel: (91) 11 4176 1620; Fax: (91) 11 4176 1630; www.hayhouse.co.in Distributed in Canada by: Raincoast Books, 2440 Viking Way, Richmond, B.C. V6V 1N2 Tel: (1) 604 448 7100; Fax: (1) 604 270 7161; www.raincoast.com Text © 2002, 2017 Laura Anne Duffy-Gipson (aka Claire Heartsong) Previously published by LightRiver Media/S.E.E Publishing (ISBN: 978-0-9844863-1-1) The moral rights of the author have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic or electronic process, or in the form of a phonographic recording; nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or otherwise be copied for public or private use, other than for ‘fair use’ as brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews, without prior written permission of the publisher. -

Habilidad Combinatoria General Y Específica De Líneas Endogámicas

Habilidad combinatoria general y específica de líneas endogámicas de maíz tolerantes a bajo fósforo General and specific combining ability of efficient corn inbreeds to low phosphorus Fredy Antonio Salazar Villarreal,1 Luis Alberto Narro León,2 Franco Alirio Vallejo Cabrera3 1/Programa AgroSalud, CIAT. Cali, Km 17 recta Cali - Palmira, A.A. 6713. Autor para correspondencia: f.salazar@cgiar. org; 2 /Programa global de maíz, CIMMYT, Colombia. CIMMYT / CIAT, Km 17 recta Cali - Palmira. AA 6713. [email protected]; 3 /Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. A.A. 237, Palmira, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. [email protected] REC.:21-11-07 ACEPT.:31-07-08 RESUMEN Los cruzamientos dialelos de 12 padres contrastantes en la toma y uso de fósforo se evaluaron en dos niveles de fósforo (4 y 15 ppm) usando un diseño experimental de alpha lattice con tres repeticiones. Se usó el diseño genético propuesto por Hallauer y Miranda. En bajo y alto fósforo se encontraron diferencias altamente significativas entre los genotipos, i.e. cruzamientos (C), padres (P) y PvsC. En alto fósforo, PvsC explicaron 58% de la suma de cuadrados de los genotipos y los cruzamientos 66% en bajo fósforo. En bajo fósforo se encontraron diferencias altamente significativas para el contraste de tolerantes (T) vs susceptibles (S). Los cruzamientos de padres TxT, SxS y TxS fueron estadísticamente diferentes, lo que sugirió que el carácter es poligénico. HCG y HCE fueron altamente significativas en los dos ambientes y HCE fue tres veces más grande, lo que sugirió que en la tolerancia a bajo fósforo son más importantes los efectos genéticos no aditivos. -

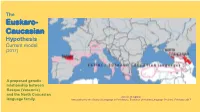

Euskaro- Caucasian Hypothesis Current Model (2017)

The Euskaro- Caucasian Hypothesis Current model (2017) A proposed genetic relationship between Basque (Vasconic) and the North Caucasian John D. Bengtson language family. Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory | Evolution of Human Language Project | February 2017 The Euskaro-Caucasian Hypothesis: Current model I. History of the hypothesis II. Description of the languages compared III. Grammatical evidence for Euskaro-Caucasian (excerpts) IV. Lexical evidence for Euskaro-Caucasian (excerpts) V. Euskaro-Caucasian Phonological correspondences (excerpts) VI. Chronology of Euskaro-Caucasian: a family about 9 millennia old VII. Anthropological scenario of Euskaro-Caucasian: linguistics, archaeology, genetics VIII. References Note: This presentation is a highly abridged summary of the evidence for this hypothesis. For more information please contact the author. I.A. The Euskaro-Caucasian hypothesis: from general to specific: The embryo of Euskaro-Caucasian (Basque as a relative of languages in the Caucasus region) was nurtured by several eminent scholars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including Hugo Schuchardt (1842-1927), Heinrich Winkler (1848–1930), Nikolay Yakovlevich Marr (1865-1934), Alfredo Trombetti (1866-1929), Christianus Cornelius Schuchardt Uhlenbeck (1866-1951), Georges Dumézil (1898-1986), René Lafon (1899-1974) and Karl Bouda (1901-1979). At the earlier stages, due to the primitive state of Caucasian linguistics, it was unclear whether the Caucasian part of the Euskaro-Caucasian family included all native Caucasian languages, South Caucasian (= Kartvelian) as well as North Caucasian (= Abkhazo- Adyghean + Nakh-Daghestanian), or only some of them. Thus, until about three decades ago, many Euskaro-Caucasian lexical and grammatical comparisons used data from Kartvelian as well as North Caucasian languages. -

Maquetación 1

El impacto de los conjuntos de trilleros en el registro paleolítico de la Meseta. Una aproximación etnoarqueológica The influence of the ‘threshing board’ sites on the Meseta Palaeolithic record. An ethnoarchaeological approach David ÁLVAREZ ALONSO*, María de Andrés HERRERO** Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología. C.A. UNED-Asturias Avda. del Jardín Botánico 1345 (calle interior) - 33203 Gijón *[email protected] **[email protected] Recibido: 15-07-2010 Aceptado: 10-03-2011 RESUMEN En el siguiente artículo se plantea la problemática que conlleva para el estudio del Paleolítico muchos depósitos líticos de carácter etnográfico y época histórica que se confunden con el registro arqueológico más antiguo. La principal aportación de este trabajo es la sistematización del proceso de elaboración de piedras de trillo en cuarcitas, y la caracterización geológica y arqueológica de estos conjuntos líticos en el territorio de Segovia. PALABRAS CLAVE: Cuarcita. Paleolítico inferior. Talla lítica. Trillo. Cantalejo. Segovia. ABSTRACT This paper analyzes the problem of the many archaeological assemblages found in the Castilian Meseta and created by the recent and contemporary activity of threshing cereals using wooden boards with stone tools (‘trillero’), which can be misinterpreted as of Palaeolithic age. The process of threshing using quartzite stones is systematically described, as well as the knapping technology used to make the cutting tools and the geological and archaeological formation of the assemblages. KEY WORDS: Quartzite. Lower Palaeolithic. Lithic technology. Threshing board. Cantalejo. Segovia. SUMARIO 1. Introducción. 2. Ámbito geográfico y geológico. 3. El trillo: origen y uso. 4. La fabricación de trillos en Cantalejo. 5. La elaboración de las piedras de trillo.