Profile of Randy Schekman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RANDY SCHEKMAN Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, USA

GENES AND PROTEINS THAT CONTROL THE SECRETORY PATHWAY Nobel Lecture, 7 December 2013 by RANDY SCHEKMAN Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, USA. Introduction George Palade shared the 1974 Nobel Prize with Albert Claude and Christian de Duve for their pioneering work in the characterization of organelles interrelated by the process of secretion in mammalian cells and tissues. These three scholars established the modern field of cell biology and the tools of cell fractionation and thin section transmission electron microscopy. It was Palade’s genius in particular that revealed the organization of the secretory pathway. He discovered the ribosome and showed that it was poised on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where it engaged in the vectorial translocation of newly synthesized secretory polypeptides (1). And in a most elegant and technically challenging investigation, his group employed radioactive amino acids in a pulse-chase regimen to show by autoradiograpic exposure of thin sections on a photographic emulsion that secretory proteins progress in sequence from the ER through the Golgi apparatus into secretory granules, which then discharge their cargo by membrane fusion at the cell surface (1). He documented the role of vesicles as carriers of cargo between compartments and he formulated the hypothesis that membranes template their own production rather than form by a process of de novo biogenesis (1). As a university student I was ignorant of the important developments in cell biology; however, I learned of Palade’s work during my first year of graduate school in the Stanford biochemistry department. -

Research Counts, Not the Journal Miguel Abambres, Tiago Ribeiro, Ana Sousa, Eva Lantsoght

Research Counts, Not the Journal Miguel Abambres, Tiago Ribeiro, Ana Sousa, Eva Lantsoght To cite this version: Miguel Abambres, Tiago Ribeiro, Ana Sousa, Eva Lantsoght. Research Counts, Not the Journal. 2018. hal-02074859v3 HAL Id: hal-02074859 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02074859v3 Preprint submitted on 15 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Abambres M, et al. (2018). Research Counts, Not the Journal, hal-02074859 © 2018 by Abambres et al. (CC BY 4.0) Research Counts, Not the Journal Miguel Abambres 1, Tiago Ribeiro 2, Ana Sousa 2 and Eva Lantsoght 3, 4 1 R&D, Abambres’ Lab, 1600-275 Lisbon, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Independent Researcher, Lisbon, Portugal 3 Researcher, Department of Engineering Structures, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands; [email protected] 4 Professor, Politécnico, Universidad San Francsico de Quito, Quito, Ecuador Abstract: ‘If there is one thing every bibliometrician agrees, is that you should never use the journal impact factor (JIF) to evaluate research performance for an article or an individual – that is a mortal sin’. -

Die Woche Spezial

In cooperation with DIE WOCHE SPEZIAL >> Autographs>vs.>#NobelSelfie Special >> Big>Data>–>not>a>big>deal,> Edition just>another>tool >> Why>Don’t>Grasshoppers> Catch>Colds? SCIENCE SUMMIT The>64th>Lindau>Nobel>Laureate>Meeting> devoted>to>Physiology>and>Medicine More than 600 young scientists came to Lindau to meet 37 Nobel laureates CAREER WONGSANIT > Women>to>Women: SUPHAKIT > / > Science>and>Family FOTOLIA INFLAMMATION The>Stress>of>Ageing > FLASHPICS > / > MEETINGS > FOTOLIA LAUREATE > CANCER RESEARCH NOBEL > LINDAU > / > J.>Michael>Bishop>and GÄRTNER > FLEMMING > JUAN > / the>Discovery>of>the>first> > CHRISTIAN FOTOLIA Human>Oncogene EDITORIAL IMPRESSUM Chefredakteur: Prof. Dr. Carsten Könneker (v.i.S.d.P.) Dear readers, Redaktionsleiter: Dr. Daniel Lingenhöhl Redaktion: Antje Findeklee, Jan Dönges, Dr. Jan Osterkamp where>else>can>aspiring>young>scientists> Ständige Mitarbeiter: Lars Fischer Art Director Digital: Marc Grove meet>the>best>researchers>of>the>world> Layout: Oliver Gabriel Schlussredaktion: Christina Meyberg (Ltg.), casually,>and>discuss>their>research,>or>their> Sigrid Spies, Katharina Werle Bildredaktion: Alice Krüßmann (Ltg.), Anke Lingg, Gabriela Rabe work>–>or>pressing>global>problems?>Or> Verlag: Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Slevogtstraße 3–5, 69126 Heidelberg, Tel. 06221 9126-600, simply>discuss>soccer?>Probably>the>best> Fax 06221 9126-751; Amtsgericht Mannheim, HRB 338114, UStd-Id-Nr. DE147514638 occasion>is>the>annual>Lindau>Nobel>Laure- Geschäftsleitung: Markus Bossle, Thomas Bleck Marketing und Vertrieb: Annette Baumbusch (Ltg.) Leser- und Bestellservice: Helga Emmerich, Sabine Häusser, ate>Meeting>in>the>lovely>Bavarian>town>of> Ute Park, Tel. 06221 9126-743, E-Mail: [email protected] Lindau>on>Lake>Constance. Die Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH ist Kooperati- onspartner des Nationalen Instituts für Wissenschaftskommunikation Daniel>Lingenhöhl> GmbH (NaWik). -

Nobel Week Stockholm 2018 – Detailed Information for the Media

Nobel Week Stockholm • 2018 Detailed information for the media December 5, 2018 Content The 2018 Nobel Laureates 3 The 2018 Nobel Week 6 Press Conferences 6 Nobel Lectures 8 Nobel Prize Concert 9 Nobel Day at the Nobel Museum 9 Nobel Week Dialogue – Water Matters 10 The Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in Stockholm 12 Presentation Speeches 12 Musical Interludes 13 This Year’s Floral Decorations, Concert Hall 13 The Nobel Banquet in Stockholm 14 Divertissement 16 This Year’s Floral Decorations, City Hall 20 Speeches of Thanks 20 End of the Evening 20 Nobel Diplomas and Medals 21 Previous Nobel Laureates 21 The Nobel Week Concludes 22 Follow the Nobel Prize 24 The Nobel Prize Digital Channels 24 Nobelprize org 24 Broadcasts on SVT 25 International Distribution of the Programmes 25 The Nobel Museum and the Nobel Center 25 Historical Background 27 Preliminary Timetable for the 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 30 Seating Plan on the Stage, 2018 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony 32 Preliminary Time Schedule for the 2018 Nobel Banquet 34 Seating Plan for the 2018 Nobel Banquet, City Hall 35 Contact Details 36 the nobel prize 2 press MeMo 2018 The 2018 Nobel Laureates The 2018 Laureates are 12 in number, including Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad, who have been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize Since 1901, the Nobel Prize has been awarded 590 times to 935 Laureates Because some have been awarded the prize twice, a total of 904 individuals and 24 organisations have received a Nobel Prize or the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel -

Randy W. Schekman, Phd

Randy W. Schekman, PhD Current Position Professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley Investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Editor-in-Chief, eLIFE Journal Education BA, molecular biology, University of California, Los Angeles PhD, biochemistry, Stanford University Awards Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2013 (shared with James E. Rothman and Thomas C. Südhof ) Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research Eli Lilly Research Award in Microbiology and Immunology Lewis S. Rosenstiel Award in Basic Biomedical Science, Brandeis University Gairdner Foundation International Award Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize, Columbia University 2008 Dickson Prize in Medicine, University of Pittsburgh E.B. Wilson Medal, American Society for Cell Biology Memberships US National Academy of Sciences American Academy of Arts and Sciences American Society of Cell Biology American Association for the Advancement of Science American Philosophical Society Biography Traffic inside a cell is as complicated as rush hour near any metropolitan area. But drivers know how to follow the signs and roadways to reach their destinations. How do different cellular proteins "read" molecular signposts to find their way inside or outside of a cell? For the past three decades, Randy Schekman has been characterizing the traffic drivers that shuttle cellular proteins as they move in membrane-bound sacs, or vesicles, within a cell. His detailed elucidation of cellular travel patterns has provided fundamental knowledge about cells and has enhanced understanding of diseases that arise when bottlenecks impede some of the protein flow. His work earned him one of the most prestigious prizes in science, the 2002 Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research, which he shared with James Rothman. -

January 24, 2020 President Donald J. Trump the White House

January 24, 2020 President Donald J. Trump The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500 Dear President Trump: As 21 Nobel Prize award-winning scientists and scholars we are writing to express our strong support for immediate open access to the results of research funded with U.S. taxpayer dollars. We understand there is an Executive Order under consideration by your Administration that would remove the 12-month embargo currently in place for access to published, taxpayer-funded research and strongly urge you to sign this order. Immediate online access to the bounty of research funded and published with U.S. support is fundamental to realising the full potential of our nation’s $65b investment in science. We must ensure that human and machine readers alike have open access to the reports, data, and code stemming from our work in order that it may be built upon swiftly, efficiently, and be translated effectively into benefits for society. Such barriers must be removed. The work of our nation’s seven million scientists 1 is inhibited so long as there are delays before we are able to read the latest work in our fields. Improving public health through the investigation of new treatments and potential cures for disease is delayed. Growing the U.S. economy through the translation of research into new services, tools and businesses is delayed. Progress across all of our fields is delayed by the embargo on access. Immediate, open online access to U.S. research will create valuable visibility. We publish our findings so that they may be read and built upon. -

Peder Sather Center for Advanced Study

Peder Sather Center for Advanced Study A Research and Educational Collaboration between Norway and the University of California, Berkeley sathercenter.berkeley.edu Peder Sather Center for Advanced Study Background and Purpose The primary mission of the Peder Sather Center for Advanced Study is to strengthen ongoing research collaborations and foster the develop- ment of new collaborations between the University of California, Berkeley and the consortium of nine participating Norwegian academic institutions. The Peder Sather Center for Advanced Study’s funding enables UC Berkeley faculty to conduct exploratory and cutting edge research in tandem with leading researchers from the following nine Norwegian higher education institutions and the Research Council of Norway: Peder Sather (1810-1886) Peder Sather, a farmer’s son from Norway, BI Norwegian Business School (BI) emigrated to New York City in 1832. Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) There he started up as a servant and lottery ticket seller before opening an exchange Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) brokerage, later to become a full-fledged University of Agder (UiA) banking house. When gold was discovered in California, banker Francis Drexel University of Bergen (UiB) offered Peder Sather and his companion, Edward Church, a large loan to establish a Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) bank in San Francisco. From 1863 Peder University of Oslo (UiO) Sather went on as the sole owner of the bank and in the late 1860’s he had become University of Stavanger (UiS) one of California’s richest men. UiT The Arctic University of Norway Peder Sather was a public-spirited man, a philanthropist and an eager supporter of The Peder Sather Center selects projects for support and serves as the public education on all levels and for both sexes. -

Nobel Prize in Medicine Honors Discoveries on How Cells Move

Nobel Prize in medicine honors discoveries on how cells move ‘cargo’ http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/2013/10/nobel-prize-in-medicine-honors-discoveries- on-how-cells-move-cargo.html By Rebecca Jacobson The 2013 Nobel Prize in Medicine is shared by three American scientists for their work on how cells move molecular "cargo" on time, which plays a major role in immune diseases, neurological diseases and diabetes. Cells manufacture neurotransmitters, hormones and enzymes, which are packaged in bubbles called vesicles and transported within the cell or exported to another cell. It's a transportation system that requires precise timing and accurate loading and unloading. When cargo piles up or is delivered late, it can contribute to disease. For example, if cells don't deliver insulin to the bloodstream on time, it can result in diabetes. Newly named Nobel Laureates James Rothman, Randy Schekman and Thomas Sudhof discovered how that delivery system works. Randy Schekman, professor of molecular and cell biology at University of California Berkeley, discovered the mutated genes which cause cargo "pile-ups" within a cell, and identified three classes of genes that control different aspects of the cell´s transport system. James Rothman, professor of cell biology at Yale University, discovered that when vesicles find the right loading dock for its cargo, they attach to their target like a zipper. It requires an exact match between vesicle and target, ensuring that molecules were delivered to the right place. Rothman and Schekman's research mapped the transport system, but timing is crucial. Thomas Südhof, professor of cell biology at Stanford University, built on Rothman and Schekman's research. -

The Molecular Machinery of Neurotransmitter Release Nobel Lecture, 7 December 2013

The Molecular Machinery of Neurotransmitter Release Nobel Lecture, 7 December 2013 by Thomas C. Südhof Dept. of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Stanford University, USA. 1. THE NEUROTRANSMITTER RELEASE ENIGMA Synapses have a long history in science. Synapses were frst functionally demon- strated by Emil duBois-Reymond (1818–1896), were morphologically identifed by classical neuroanatomists such as Rudolf von Kölliker (1817–1905) and San- tiago Ramon y Cajal (1852–1934), and named in 1897 by Michael Foster (1836– 1907). Although the chemical nature of synaptic transmission was already sug- gested by duBois-Reymond, it was long disputed because of its incredible speed. Over time, however, overwhelming evidence established that most synapses use chemical messengers called neurotransmitters, most notably with the pioneer- ing contributions by Otto Loewi (1873–1961), Henry Dale (1875–1968), Ulf von Euler (1905–1983), and Julius Axelrod (1912–2004). In parallel, arguably the most important advance to understanding how synapses work was provided by Bernard Katz (1911–2003), who elucidated the principal mechanism of syn- aptic transmission (Katz, 1969). Most initial studies on synapses were carried out on the neuromuscular junction, and central synapses have only come to the fore in recent decades. Here, major contributions by many scientists, including George Palade, Rodolfo Llinas, Chuck Stevens, Bert Sakmann, Eric Kandel, and Victor Whittaker, to name just a few, not only confrmed the principal results obtained in the neuromuscular junction by Katz, but also revealed that synapses 259 6490_Book.indb 259 11/4/14 2:29 PM 260 The Nobel Prizes exhibit an enormous diversity of properties as well as an unexpected capacity for plasticity. -

A Nobel Prize for Cell Biology

editorial A Nobel Prize for cell biology ‘‘The prize is a landmark his year’s Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Günter Blobel, of the Rockefeller University, for ‘‘the discovery that proteins have intrinsic signals that gov- in its recognition of the Tern their transport and localisation in the cell’’. Angus Lamond of the University of Dun- dee says that the prize is “a landmark in its recognition of the fundamental importance of basic fundamental importance research in molecular cell biology for modern medicine and the fight against disease”. of basic research in The idea that proteins contain targeting zip codes originated in 1971, when Blobel and his colleague David Sabatini postulated that the information needed to direct a nascent peptide to molecular cell biology the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum is contained within the peptide itself. A year later, César Milstein and colleagues provided experimental evidence for a transient signal sequence at for modern medicine the amino-terminal end of a secretory protein. Building on this important discovery and work from his own laboratory, Blobel, together with Bernhard Dobberstein, formulated the ‘signal and the fight against hypothesis’. In a 1975 paper — which has since become a citation classic — they predicted that newly synthesized proteins have a built-in signal which directs them to the endoplasmic disease’’ reticulum and through a channel in the membrane. This principle has turned out to be a common mechanism, operating in a variety of intracellular pathways in all organisms, from bacteria to yeast to man. According to Peter Walter of the University of San Francisco, ‘‘Günter’s accomplishment is not defined by a single paper or even a set of papers, but rather is the fruit of his casting a wide net over a fundamentally important problem in biology. -

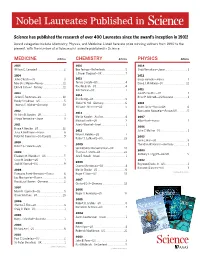

Nobel Laureates Published In

Nobel Laureates Published in Science has published the research of over 400 Laureates since the award’s inception in 1901! Award categories include Chemistry, Physics, and Medicine. Listed here are prize-winning authors from 1990 to the present, with the number of articles each Laureate published in Science. MEDICINE Articles CHEMISTRY Articles PHYSICS Articles 2015 2016 2014 William C. Campbell . 2 Ben Feringa —Netherlands........................5 Shuji Namakura—Japan .......................... 1 J. Fraser Stoddart—UK . 7 2014 2012 John O’Keefe—US...................................3 2015 Serge Haroche—France . 1 May-Britt Moser—Norway .......................11 Tomas Lindahl—US .................................4 David J. Wineland—US ............................12 Edvard I. Moser—Norway ........................11 Paul Modrich—US...................................4 Aziz Sancar—US.....................................7 2011 2013 Saul Perlmutter—US ............................... 1 2014 James E. Rothman—US ......................... 10 Brian P. Schmidt—US/Australia ................. 1 Eric Betzig—US ......................................9 Randy Schekman—US.............................5 Stefan W. Hell—Germany..........................6 2010 Thomas C. Südhof—Germany ..................13 William E. Moerner—US ...........................5 Andre Geim—Russia/UK..........................6 2012 Konstantin Novoselov—Russia/UK ............5 2013 Sir John B. Gurdon—UK . 1 Martin Karplas—Austria...........................4 2007 Shinya Yamanaka—Japan.........................3 -

Dr. Randy Schekman

Dr. Randy Schekman 2013 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine Professor of Molecular and Cell Biology University of California, Berkeley ISTeC Distinguished Lecture In conjunction with the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, Computer Science Department, and CSU Libraries “Publishing Your Most Important Work” Monday, March 24, 2014 Lecture: 4:00 – 5:00 pm Location: Behavioral Sciences Building Rm. 131 • Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, Computer Science Department, and Biology Department Special Seminar Sponsored by ISTeC “Genes and Proteins that Control Secretion and Autophagy” Monday, March 24, 2014 Lecture: 11:00 am – 12:00 noon Location: LSC Theater ISTeC (Information Science and Technology Center) is a university-wide organization for promoting, facilitating, and enhancing CSU's research, education, and outreach activities pertaining to the design and innovative application of computer, communication, and information systems. For more information please see ISTeC.ColoState.EDU. Abstracts: Publishing Your Most Important Work The assessment of scholarly achievement depends critically on the proper evaluation and publication of research work in scholarly journals. Investigators face a dizzying array of journal styles that include commercial, not-for-profit and academic society journals that are supported by a mix of subscription and page charges. The Open Access (OA) movement, launched in Britain but greatly expanded by the Public Library of Science (PLoS), seeks to eliminate the firewall that separates published work from public access. OA journals are funded by a mix of page charges and philanthropic or foundation support. Most OA journals embrace a more liberal licensing agreement on the use and reuse of published work, favoring the creative commons license rather than a copyright held by the publisher.