Why All the Outrage? Viral Media As Corrupt Play Shaping Mainstream Media Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATISTICS 2019-20 Meg Lanning CONTENTS

WACA STATISTICS 2019-20 Meg Lanning CONTENTS Ground Records 2 International Records for WA Players 4 Domestic Records for WA Players 5 Laurie Sawle Medal & Zoë Goss Medal Winners 7 INTERNATIONAL 8 Players selected from Western Australia to represent Australia in Test Matches and Touring Teams 8 Test Match Records for WA Players 15 One Day International Records for WA Players 17 Twenty20 International Records for WA Players 19 Test Match Records for WA Female Players 20 One Day International Records for WA Female Players 21 Twenty20 International Records for WA Female Players 22 DOMESTIC 23 WA’s First Class Record from 1892 23 Interstate & International Matches 24 Career Records for WA & WA Combined XI 31 Sheffield Shield 38 Batting Averages 40 Bowling Averages 44 Wicket-Keepers 48 Century Partnerships 49 First Class 57 Century Makers 57 Centuries at Each Venue 61 Centuries 62 Outstanding Bowling Performances 67 Five Wickets or More in an Innings 70 Domestic One Day 73 One Day Records 76 Domestic Twenty20 82 Western Warriors 82 Perth Scorchers Big Bash League 84 Combined Domestic T20 Career Records 87 Women's National Cricket League 89 WNCL Career Records 91 Women's Twenty20 93 WT20 Career Records 93 Perth Scorchers Women's Big Bash League 95 WBBL Career Records 96 Combined WT20 & WBBL Career Records 97 These statistics have been updated by Karl Shunker and Patrick Henning. PREMIER CRICKET 98 The WACA also thanks WA Cricket Historian Bill Reynolds for his contribution. First Grade Aggregates, Averages & Awards 100 Premier Cricket 104 Cover: -

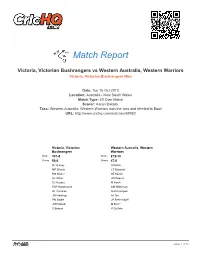

Match Report

Match Report Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers vs Western Australia, Western Warriors Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers Won Date: Tue 15 Oct 2013 Location: Australia - New South Wales Match Type: 50 Over Match Scorer: Aaron Bakota. Toss: Western Australia, Western Warriors won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/69082 Victoria, Victorian Western Australia, Western Bushrangers Warriors Score 331-8 Score 272-10 Overs 50.0 Overs 47.0 RJ Quiney S Katich MP Stoinis CT Bancroft MS Wade* SE Marsh CL White JW Rogers DJ Hussey M North PSP Handscomb SM Whiteman DT Christian N Rimmington JW Hastings AJ Tye PM Siddle JP Behrendorff JM Holland M Beer* S Boland R Duffield page 1 of 36 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers R B 4's 6's SR RJ Quiney . 4 4 . 1 . 1 4 . 4 2 4 . 1 . 1 1 . 4 . 2 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . // c AJ Tye b AJ Tye 37 37 6 0 100.0 MP Stoinis . 4 . 4 2 . 1 . 1 . 2 1 1 . 1 . run out (CT Bancroft) 63 92 5 2 68.48 2 . 1 . 4 6 . 4 . 1 . 4 . 1 . 1 1 6 . 1 1 . 1 . 5 1 2 1 1 1 1 . // MS Wade* . 4 . 4 . 1 . 1 . 4 2 . 1 1 1 4 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 1 1 4 . 1 lbw b M Beer* 74 82 9 1 90.24 . 1 1 2 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 4 . 1 1 1 . 6 1 1 4 1 1 1 . 2 . // CL White . 4 . 1 . -

Philpott S. the Politics of Purity: Discourses of Deception and Integrity in Contemporary International Cricket

Philpott S. The politics of purity: discourses of deception and integrity in contemporary international cricket. Third World Quarterly 2018, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1432348. Copyright: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Third World Quarterly on 07/02/2018, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01436597.2018.1432348. DOI link to article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1432348 Date deposited: 23/01/2018 Embargo release date: 07 August 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk 1 The politics of purity: discourses of deception and integrity in contemporary international cricket Introduction: The International Cricket Council (ICC) and civil prosecutions of three Pakistani cricketers and their fixer in October 2011 concluded a saga that had begun in the summer of 2010 with the three ensnared in a spot-fixing sting orchestrated by the News of the World newspaper. The Pakistani captain persuaded two of his bowlers to bowl illegitimate deliveries at precise times of the match while he batted out a specific over without scoring a run. Gamblers with inside knowledge bet profitably on these particular occurrences. This was a watershed moment in international cricket that saw corrupt players swiftly exposed unlike the earlier conviction of the former and now deceased South African captain Hansie Cronje whose corruption was uncovered much -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing. -

Sachin Tendulkar SYDNEY: the Australian Players, MUMBAI: Former India Batsman Accept to Those Things," He Said

FRITZ KELLER, German football fed- eration (DFB) president resigned on TUESDAY, SILCHAR Monday after comparing vice presi- 10 MAY 18, 2021 SportChronicle dent Rainer Koch to a Nazi judge. Australians in IPL arrive in Sydney, Dealt with anxiety for 10-12 Nadal outwits Djokovic set to quarantine for two weeks years: Sachin Tendulkar SYDNEY: The Australian players, MUMBAI: Former India batsman accept to those things," he said. coaches and commentary staff and captain Sachin Tendulkar Tendulkar, who is the high- for 10th Rome Open title who were in the 2021 IPL arrived said he had to deal with anxi- est run-scorer of all time in Test in Sydney on Monday from the ety before a match even after and ODI cricket and the only final. Nadal, on the other hand, Maldives and will be in quaran- he had spent several years in cricketer to score 100 interna- TENNIS needed an hour-and-a-half-to tine for 14 days. international cricket. tional centuries, said that he felt AGENCIES take down Reilly Opelka of the The cricketers had gone to "Pressure, anxiety and all the effects of anxiety for about USA. Djokovic, who was bid- the Maldives after the suspen- were always there. In my case, 10-12 years. "Then I started ROME: World No. 3 Spaniard ding to record his first win on sion of the tournament as the I realised all my preparations accepting that it was part of my Rafael Nadal on Sunday won clay against the Spaniard since Australian government had were there in a physical sense. -

Ian Chappell

Monday 25th September, 2006 11 Kuala Lumpur – Remember if you brow. It was about 2.06 pm. Meckiff will, Yahaluweni, the clumsy efforts of again ran in off his short run-up . the George (WMD) Bush when visiting crowd hushed and again came the call Pakistan not so long ago. There he was, 'No b-a-I-I!' from Egar. The spectators facing a few Pakistan net bowlers and now reacted angrily and booed the making a fool of himself again. Inzamam and Ponting need umpire. It was ugly all right. Did Bush, though, when talking to Benaud moved over to Meckiff as the Pakistan's President Pervez Musharraf atmosphere in the ground became super- the other day, bring up the subject of charged and spectators boiled with rage. how Pakistan were going to handle the 'Well, Meck, I think we've got a bit of Darrell Hair issue? Highly unlikely. The a problem, don't you. I don't quite know pretentious Yanks pretend they know a to know the laws what we should do,' he said, as the cat- lot about most things, but hairy subjects calling of the umpires went on. 'Either as ball tampering is a bit beyond their after Hair offered to quit for US$500,000. Aussie vernacular, challenging man would curse the umpire. Quirk bowl as quickly as you can, or bowl it grasp of intellect. That’s as crass as England coach David Tendulkar who was allowed to carry on later became a radio and television slow and get through the over.' 'Hair?' asked a mystified Condoleezza (Bumble) Lloyd and his famous remarks his innings. -

Page 1 TEAM CARD CHECKLIST Adelaide Strikers Brisbane Heat

t, I I I ,' I,' I I I TEAIUI CARD CHECKLIST l I ,,t I .: l. I Adelaide Brisbane Hobart Iulelbourne ,lI.i I Strikers Heat Hurricanes Renegades ti I 57 TravisHead 75 Chris-Lynn George Bailey 777 AaronFinch r'I I 58 AlexCarey 76 JoeBurns Jofra Archer 772 CameronBoyce 59 Rashid l(han n Ben Cutting QaisAhmed 113 Dan Christian I I 60 Ben laughlin 78 AB De Villiers Jal<e Doran 714 TomCooper l I 67 Jake.Lehmann 79 SamHeazlett James Faull<ner 775 HarryGurney I I 62 lvlichael I\Ieser 80 JamesPattinson Caleb Jewell Ll6 l{arcus Harris 63 Ilarry.lVielsen 87 Jimmy Peirson Ben McDermott 777 l(ane Richardson l, I il PeterSiddle 82 Itlatthew Renshaw . Simon Milenko t28 Will Sutherland .l I 55 BillyStanlake 83 lfarkSteketee D'Arcy Short 179 BeauWebster t, t 66 JakeWeatherald 84 Mujeeb Uri?ahman Matthew Wade 72A JackWildermuth 67 SuzieBates 85 RirbyShort Stelanie Daffara 121 lvlaitlan Brcwn '' J, I 68 Sarah0oyte 88 HaideeBirkett Erin Fazackerley 722 JessDuttin I I 69 Sophie Devine 87 Grace Harris Ihtelyn Fryett 723 Erica lGrshaw 70 Amanda Jade Wellington 88 Sammy-Jo Johnson Corrine Hall 724 Sophie l{olineux I I Alex Hartley 725 Lea?ahuhu ,.1, 71 TahlialtlcGrath 89 JessJonassen I 72 BridgetPatterson 90 Delissa I(immince lvleg Phillips 726 GeorgiaWareham :* I 73 TabathaSaville 97 BethMooney Heather lhight 727 CourtneyWebb 74 lvfegan Schutt Se GeorgiaPrestwidge Hayley Matthews 128 DanniWyatt .I;: l,' I I I I Plelbourne Perth Sydney Sydney I I Stars Scorchers Sixers Thunder I I 729 Jackson0oleman 747 AshtonAgar lUoises Henrigues 783 JosButler 13A BenDunk 74A CamercnBancroft Sean Abbott 784 CallumFerguson T I 137 PeterHandscomb 749 JasonBehrendortf Tom Curran 785 Matt Gilkes .'I I 732 Sandeep.Lamichhane ,5A CameronGreen . -

Matador Bbqs One Day Cup Winners “Some Plan B’S Are Smarter Than Others, Don’T Drink and Drive.” NIGHTWATCHMAN NATHAN LYON

Matador BBQs One Day Cup Winners “Some plan b’s are smarter than others, don’t drink and drive.” NIGHTWATCHMAN NATHAN LYON Supporting the nightwatchmen of NSW We thank Cricket NSW for sharing our vision, to help develop and improve road safety across NSW. Our partnership with Cricket NSW continues to extend the Plan B drink driving message and engages the community to make positive transport choices to get home safely after a night out. With the introduction of the Plan B regional Bash, we are now reaching more Cricket fans and delivering the Plan B message in country areas. Transport for NSW look forward to continuing our strong partnership and wish the team the best of luck for the season ahead. Contents 2 Members of the Association 61 Toyota Futures League / NSW Second XI 3 Staff 62 U/19 Male National 4 From the Chairman Championships 6 From the Chief Executive 63 U/18 Female National 8 Strategy for NSW/ACT Championships Cricket 2015/16 64 U/17 Male National 10 Tributes Championships 11 Retirements 65 U/15 Female National Championships 13 The Steve Waugh/Belinda Clark Medal Dinner 66 Commonwealth Bank Australian Country Cricket Championships 14 Australian Representatives – Men’s 67 National Indigenous Championships 16 Australian Representatives – Women’s 68 McDonald’s Sydney Premier Grade – Men’s Competition 17 International Matches Played Lauren Cheatle in NSW 73 McDonald’s Sydney Premier Grade – Women’s Competition 18 NSW Blues Coach’s Report 75 McDonald’s Sydney Shires 19 Sheffield Shield 77 Cricket Performance 24 Sheffield Shield -

Race and Cricket: the West Indies and England At

RACE AND CRICKET: THE WEST INDIES AND ENGLAND AT LORD’S, 1963 by HAROLD RICHARD HERBERT HARRIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2011 Copyright © by Harold Harris 2011 All Rights Reserved To Romelee, Chamie and Audie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My journey began in Antigua, West Indies where I played cricket as a boy on the small acreage owned by my family. I played the game in Elementary and Secondary School, and represented The Leeward Islands’ Teachers’ Training College on its cricket team in contests against various clubs from 1964 to 1966. My playing days ended after I moved away from St Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where I represented Ridley Cricket Club against teams as distant as 100 miles away. The faculty at the University of Texas at Arlington has been a source of inspiration to me during my tenure there. Alusine Jalloh, my Dissertation Committee Chairman, challenged me to look beyond my pre-set Master’s Degree horizon during our initial conversation in 2000. He has been inspirational, conscientious and instructive; qualities that helped set a pattern for my own discipline. I am particularly indebted to him for his unwavering support which was indispensable to the inclusion of a chapter, which I authored, in The United States and West Africa: Interactions and Relations , which was published in 2008; and I am very grateful to Stephen Reinhardt for suggesting the sport of cricket as an area of study for my dissertation. -

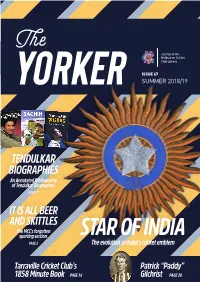

TENDULKAR BIOGRAPHIES an Annotated Bibliography of Tendulkar Biographies

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library ISSUE 67 SUMMER 2018/19 TENDULKAR BIOGRAPHIES An Annotated Bibliography of Tendulkar Biographies. PAGE 11 IT IS ALL BEER AND SKITTLES The MCC's forgotten sporting section. STAR OF INDIA PAGE 3 The evolution as India’s cricket emblem Tarraville Cricket Club’s Patrick “Paddy” 1858 Minute Book PAGE 14 Gilchrist PAGE 20 ISSN 1839-3608 PUBLISHED BY THE MELBOURNE CRICKET CLUB CONTENTS: © THE AUTHORS AND THE MCC The Yorker is edited by Trevor Ruddell with the assistance of David Studham. It’s all Beer and Life in the MCC Graphic design and publication by 3 Skittles 16 Library George Petrou Design. Thanks to Jacob Afif, James Brear, Lynda Carroll, Edward Cohen, Gaye Fitzpatrick, Stephen Flemming, Helen Hill, James Howard, The Star of India Patrick “Paddy” Quentin Miller, Regan Mills, George Petrou, Trevor Ruddell, Ann Rusden, Andrew Lambert, 8 20 Gilchrist Michael Roberts, Lesley Smith, David Studham, Stephen Tully, Andrew Young, and our advertiser Roger Pager Cricket Books. Tendulkar The views expressed are those of the 11 Biographies A Nation’s Undying editors and authors, and are not those of the Melbourne Cricket Club. All reasonable 26 Love for the Game attempts have been made to clear copyright before publication. The publication of an advertisement does not Tarraville Cricket imply the approval of the publishers or the MCC 14 Club’s 1858 Minute Book Reviews for goods and services offered. Published three times a year, the Summer Book 28 issue traditionally has a cricket feature, the Autumn issue has a leading article on football, while the Spring issue is multi-sport focused. -

The Big Three Era Starts

151 editions of the world’s most famous sports book WisdenEXTRA No. 12, July 2014 England v India Test series The Big Three era starts now Given that you can bet on almost anything these most recent book was a lovely biography of Bishan days, it would have been interesting to know the odds Bedi – a stylist who played all his international cricket on the first Test series under N. Srinivasan’s ICC before India’s 1983 World Cup win and the country’s chairmanship running to five matches. (Actually, on wider liberalisation. Since then, the IPL has moved the reflection, let’s steer clear of the betting issue.) But goalposts once again. Menon is in an ideal position to certainly, until this summer, many assumed that – examine what Test cricket means to Indians across the barring the Ashes – the five-Test series was extinct. Yet, social spectrum. here we are, embarking on the first since 2004-05 – The Ranji Trophy has withstood all this to remain when England clung on to win 2–1 in South Africa. the breeding ground for Indian Test cricketers. Although Not so long ago, five- or even six-match series it has never commanded quite the same affection as between the leading Test nations were the core of the the County Championship, it can still produce its fair calendar. Sometimes, when it rained in England or share of romance. We delve into the Wisden archives someone took an early lead in the subcontinent, the to reproduce Siddhartha Vaidyanathan’s account of cricket could be dreary in the extreme. -

Sample Download

Contents Foreword by Jeff Crowe 9 Acknowledgements 15 Line in the Sand 17 I’m Out 37 Teamwork 52 Man Management 76 Burnt Out 103 Gunner of the Gunners 125 Middlesex Matters 150 Sussex by the Sea 174 England 206 Never Go Back 225 On the Circuit 242 What’s Next? 262 Bibliography 286 1 Line in the Sand KNOW this might surprise a few people who love cricket and watch a lot of it, but most top umpires prepare for games as fastidiously as players. From Ithe day I joined the International Cricket Council (ICC)’s elite panel in 2008, two years after I stood in my first international at the Oval, I trained for every game, and in particular Test matches, in pretty much the same way and certainly with a bit more professionalism than when I played for England back in the 1980s when warm-ups usually consisted of a few laps of the outfield and some stretches with the physio Bernard Thomas, who was the equivalent of a modern-day strength and conditioning coach back then. Two days before the game started, I would go down to the ground, dump my gear in the umpires’ 17 GUNNER: MY LIFE IN CRICKET room, wander over to the nets and stand at one end during each team’s practice and just observe. When you think about it, it’s an obvious thing to do. The international game moves so quickly these days that when I began a new series in a different country there were invariably bowlers and batsmen who I had not come across before.