Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scoresheet NEWSLETTER of the AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC

scoresheet NEWSLETTER OF THE AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC. www.australiancricketsociety.com.au Volume 38 / Number 2 /AUTUMN 2017 Patron: Ricky Ponting AO WINTER NOSTALGIA LUNCHEON: Featuring THE GREAT MERV HUGHES Friday, 30 June, 2017, 12 noon for a 12.25 start, The Kelvin Club, Melbourne Place (off Russell Street), CBD. COST: $75 – members & members’ partners; $85 – non-members. TO GUARANTEE YOUR PLACE: Bookings are essential. This event will sell out. Bookings and moneys need to be in the hands of the Society’s Treasurer, Brian Tooth at P.O. Box 435, Doncaster Heights, Vic. 3109 by no later than Tuesday, 27 June, 2017. Cheques should be made payable to the Australian Cricket Society. Payment by electronic transfer please to ACS: BSB 633-000 Acc. No. 143226314. Please record your name and the names of any ong-time ACS ambassadors Merv Hughes is guest of honour at our annual winter nostalgia luncheon at the guests for whom you are Kelvin Club on Friday, June 30. Do join us for an entertaining afternoon of reminiscing, story-telling and paying. Please label your Lhilariously good fun – what a way to end the financial year! payment MERV followed by your surname – e.g. Merv remains one of the foremost personalities in Australian cricket. His record of four wickets per Test match and – MERVMANNING. 212 wickets in all Tests remains a tribute to his skill, tenacity and longevity. Standing 6ft 4in in the old measure Brian’s phone number for Merv still has his bristling handle-bar moustache and is a crowd favourite with rare people skills. -

Du Plessis, Miller Hit Centuries

SPORTS Thursday, February 2, 2017 19 Football scores India clinch series 2-1 Copa del Rey: Semi-final, first leg: Atletico Madrid v Barcelona (2000) Bangalore who received the man of the match and series ndia skipper Virat Kohli award for his eight scalps in three games, got yesterday said he has faith great support from seamer Jasprit Bumrah’s three Italian Serie A: in YuzvendraI Chahal’s abilities wickets. Pescara 1 Fiorentina 2 after the leg spinner claimed six “I have a lot of faith in him, and he plays Scottish Premiership: wickets to set up his country’s with a lot of confidence. He has a lot of skill Celtic 1 Aberdeen 0 75-run series-clinching and he has the character as well,” Kohli said of Hearts 4 Rangers 1 victory in the third Twenty20 his wily spinner who played just his sixth T20 international in Bangalore. international. Africa Cup of Nations semi-final: Chahal recorded his T20 best of The attacking spinner started England’s batting 6-25 to help skittle out rot in the 14th over of the innings, getting Egypt 4 Burkina Faso 3 England for 127 dangermen Joe Root (42) and skipper Eoin in 16.3 overs. Morgan (40) on consecutive deliveries to derail The visitors, the tourists’ chase. French Cup results on Wednesday chasing Root and Morgan had kept the chase alive with (aet denotes after extra time) 203, lost their 64-run third-wicket stand but the innings Angers 3 Caen 1 eight fell apart after their departure. CA Bastia 2 Nancy 0 Chahal got three wickets US Avranches 1 Fleury 91 FC 0 in his fourth over to rip through Fréjus Saint-Raphaël 1 Prix-lès-Mézières 0 the England middle and Les Herbiers 1 Guingamp 2 aet lower order -- five batsmen FC Chambly 4 Monaco 5 aet wickets were out on zero -- as India Auxerre 3 Saint-Etienne 0 aet for eight won the series 2-1. -

REPORT Th ANNUAL 2012 -2013 the 119Th Annual Report of New Zealand Cricket Inc

th ANNUAL 119 REPORT 2012 -2013 The 119th Annual Report of New Zealand Cricket Inc. 2012 - 2013 OFFICE BEARERS PATRON His Excellency The Right Honourable Sir Jerry Mateparae GNZM, QSO, Governor-General of New Zealand PRESIDENT S L Boock BOARD CHAIRMAN C J D Moller BOARD G Barclay, W Francis, The Honourable Sir John Hansen KNZM, S Heal, D Mackinnon, T Walsh CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER D J White AUDITOR Ernst & Young, Chartered Accountants BANKERS ANZ LIFE MEMBERS Sir John Anderson KBE, M Brito, D S Currie QSO, I W Gallaway, Sir Richard J Hadlee, J H Heslop CBE, A R Isaac, J Lamason, T Macdonald QSM, P McKelvey CNZM MBE, D O Neely MBE, Hon. Justice B J Paterson CNZM OBE, J R Reid OBE, Y Taylor, Sir Allan Wright KBE 5 HONORARY CRICKET MEMBERS J C Alabaster, F J Cameron MBE, R O Collinge, B E Congdon OBE, A E Dick, G T Dowling OBE, J W Guy, D R Hadlee, B F Hastings, V Pollard, B W Sinclair, J T Sparling STATISTICIAN F Payne NATIONAL CODE OF CONDUCT COMMISSIONER N R W Davidson QC 119th ANNUAL REPORT 2013 REPORT 119th ANNUAL CONTENTS From the NZC Chief Executive Officer 9 High Performance Teams 15 Family of Cricket 47 Sustainable Growth of the Game 51 Business of Cricket 55 7 119th ANNUAL REPORT 2013 REPORT 119th ANNUAL FROM THE CEO With the ICC Cricket World Cup just around the corner, we’ll be working hard to ensure the sport reaps the benefits of being on the world’s biggest stage. -

Swiatek Ousts Top Seed Halep; Nadal Bests Korda

Sports Monday, October 5, 2020 15 Teen shock: Swiatek Indian Premier League ousts top seed Halep; Nadal bests Korda DPA LONDON Shane Watson (left) and Faf du Plessis shared an unbroken 181-run WOMEN’S top seed Simo- stand for the first wicket - the highest ever for the Chennai Super na Halep crashed out of the Kings in the IPL in Dubai on Sunday. French Open fourth round on Sunday after the world num- ber two was stunned 6-1, 6-2 Watson, Du Plessis fire in 68 minutes by Polish teen- ager Iga Swiatek. as CSK humble KXIP Fifth seed Kiki Bertens of the Netherlands is also out AFP “I am known for swing after losing 6-4, 6-4 to Italy’s DUBAI and not for slower ones with Martina Trevisan, who will the new ball, but you just use share a first-ever Grand Slam NEW Zealand quick Trent variations and angles.” quarter-final with Swiatek. Boult returned figures of Boult got the key wickets “I felt like I was playing 2-28 as he overcame hot of England batsman Jonny perfectly,” Swiatek said in an Spain’s Rafael Nadal celebrates after winning against Sebastian UAE weather to help holders Bairstow for 25 and his na- interview on Court Philippe Korda of the US on Sunday. (AFP) Mumbai Indians reach top of tional captain Kane William- Chatrier. “I was so focused the Indian Premier League son, caught behind for three, the whole match and I’m sur- table on Sunday. to choke David Warner’s Hy- prised I could do that. -

Mathematical Models for Cricket Team Selection

Mathematical Models for Cricket Team Selection Hamish Thorburn Dr Michael Forbes The University of Queensland 26/02/2015 1 1 Abstract An attempt was made to try and select the Australian Test Cricket Team for then-upcoming series against India in December-January 2014-2015. Data was collected pertaining to 37 Australian cricket players, relating to both recent form (the 12 months prior to commencement of the project) and career form across multiple formats of the game. The team was selected using a mixed-integer- programming (MIP) model, after processing the statistics collected to create usable parameters for the model. It was found that the team selected by the MIP model shared only 5 of the 11 players with the actual team selected by the Australian Board of Selectors to compete in the series. When altering parameters of the model, it was found that the batting diversity of the team could be doubled while only losing 0.008 of the available talent of selected players. The reduced costs were calculated to determine how close unselected players were to being selected, and what they would have to increase their batting/bowling averages to be considered for selection. Finally, we compared the ICC player ratings to our calculated batting and bowling indices, to try to determine the optimal weighting between the different statistics. It was found that batting average was most important in batting performance (but was more important in test matches than one-day matches) and that bowling average and economy were equally important in bowling performance. 2 Introduction 2.1 The Game of Cricket Cricket is a sport composing of opposing teams of 11 players each side. -

P13 5 Layout 1

Established 1961 13 Sports Monday, January 8, 2018 Cooked England lurching to defeat after Marsh brothers’ tons Cook becomes sixth batsman to score 12,000 test runs SYDNEY: Nathan Lyon was hailed as Australia’s “key” bowler as the team closes in on an emphatic victory in the final Ashes Test after beleaguered England unravelled on a torrid day in Sydney yesterday. The Australians amassed a massive 303-run innings lead in blistering heat and then reduced the battle-weary tourists to 93 for four at the close with a day to play. Compounding England’s woes was a finger injury for skipper Joe Root, his team’s last major hope of staving off a 4-0 series rout today’s final day of the Test. Root was unbeaten on 42 at the close with Jonny Bairstow not out 17. Lyon captured the important wickets of Alastair Cook and Dawid Malan to have two for 31 off 19 overs at stumps. “I think Gaz (Lyon) is the key tomorrow. SYDNEY: Australia’s Mitchell Marsh (R) sends his brother Sahun Marsh (L) back to his crease The wicket is definitely suiting his conditions, as he celebrates scoring his century against England on the fourth day of the fifth Ashes especially with the left handers, he’ll come cricket Test match at the SCG in Sydney yesterday, — AFP into play,” Australian centurion Shaun Marsh SCOREBOARD said. “I thought he bowled really well today Mitchell Marsh was bowled next ball by and showed his class and hopefully he can TON-UP BROTHERS Tom Curran for 101 off 141 balls with 15 fours come out tomorrow and get a few early “In many ways the last few days have and two sixes. -

Vol. Xcvi1 No. 3 September 2012

VOL. XCVI1 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2012 THE DIOCESAN COLLEGE, RONDEBOSCH College Address: Campground Road, Rondebosch, 7700, Tel 021 659 1000, Fax 021 659 1013 Prep Address: Fir Road, Rondebosch, 7700; Tel 021 659 7220 Pre-Prep Address: Sandown Road, Rondebosch, 7700; Tel 021 659 1037/47 Editor: Mr CW Tucker [email protected] OD Union E-mail: [email protected] Museum and Archives: Mr B Bey [email protected] website: www.bishops.org.za FOUNDED IN 1849 BY THE BISHOP OF CAPE TOWN, AS A CHRISTIAN FOUNDATION INCORPORATED BY ACT OF PARLIAMENT, 1891 Visitor HIS GRACE THE ARCHBISHOP OF CAPE TOWN THABO CECIL MAKGOBA Members of the College Council Chairman Mr MJ Bosman Bishop GQ Counsell, Dr R Nassen, Mrs M Isaacs, Prof HI Bhorat, AVR Taylor, P Anderson, M Bourne, J Gardener, S Utete Principal: Mr G nupen, B. Com, HED Deputy Principal: Mr Ma King, MA, MA, BA (Hons), NHED, B Ed (St Andrews Rhodes Scholar) COLLEGE STAFF Headmaster: Mr v Wood, B Ed, BA, HDE Deputy Headmasters Mr aD Mallett, BA, HDE Mr MS Bizony, B.Sc (Hons) Mr D abrey, B.Sc, PGCE Mr pG Westwood, B.Sc (Hons) Mr R Drury, BA, HDE Mr a Jacobs, PTD, HDE Mr W Wallace, BA (Hons), HDE Assistant Deputy Headmasters Mr S Henchie, MA (Economics) Mr M Mitchell, MBA, M Mus, HDE, LTCL, FTCL, UPLM, UTLM Ms B Kemball, BA, HDE, FDE (I SEN) Mr p Mayers, B Music Education Mr K Kruger; B Sc (Erg), HDE Mr D Russell, B Com, HDE Academic Staff Mr R Jacobs, B.Sc(Ed) Mr RpO Hyslop, BA (FA), HDE Mr J nolte, B.Soc.Sci (Hons); B Psych, PGCE Mr pL Court, BA (Hons), BA, HDE Mr R Smith, BA (Hons) SportsSci (Biokmetics), -

ICC Annual Report 2014-15

ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 INCLUDING SUMMARISED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OUR VISION OF SUCCESS AS A LEADING GLOBAL SPORT, CRICKET WILL CAPTIVATE AND INSPIRE PEOPLE OF EVERY AGE, GENDER, BACKGROUND AND ABILITY WHILE BUILDING BRIDGES BETWEEN CONTINENTS, COUNTRIES AND COMMUNITIES. Strategic Direction A BIGGER, BETTER, GLOBAL GAME TARGETING MORE PLAYERS, MORE FANS, MORE COMPETITIVE TEAMS. Our long-term success will be judged on growth in participation and public interest and the competitiveness of teams participating in men’s and women’s international cricket. Mission Statement AS THE INTERNATIONAL GOVERNING BODY FOR CRICKET, THE INTERNATIONAL CRICKET COUNCIL WILL LEAD BY: • Providing a world class environment for international cricket • Delivering ‘major’ events across three formats • Providing targeted support to Members • Promoting the global game Our Values THE ICC’S ACTIONS AND PEOPLE ARE GUIDED BY THE FOLLOWING VALUES: • Fairness and Integrity • Excellence • Accountability • Teamwork • Respect for diversity • Commitment to the global game and its great spirit 01 CONTENTS FOREWORD 02 Chairman’s Report 04 Chief Executive’s Report 06 Highlights of the Year 08 Obituaries & Retirements DELIVERING MAJOR EVENTS 12 ICC Cricket World Cup 2015 20 ICC Women’s Championship 22 Pepsi ICC World Cricket League PROMOTING THE GLOBAL GAME 26 LG ICC Awards 2014 28 ICC Cricket Hall of Fame 30 Cricket’s Great Spirit PROVIDING A WORLD-CLASS ENVIRONMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL CRICKET 34 Governance of the Global Game 36 ICC Members 38 Development 40 Commercial 42 Cricket -

STATISTICS 2019-20 Meg Lanning CONTENTS

WACA STATISTICS 2019-20 Meg Lanning CONTENTS Ground Records 2 International Records for WA Players 4 Domestic Records for WA Players 5 Laurie Sawle Medal & Zoë Goss Medal Winners 7 INTERNATIONAL 8 Players selected from Western Australia to represent Australia in Test Matches and Touring Teams 8 Test Match Records for WA Players 15 One Day International Records for WA Players 17 Twenty20 International Records for WA Players 19 Test Match Records for WA Female Players 20 One Day International Records for WA Female Players 21 Twenty20 International Records for WA Female Players 22 DOMESTIC 23 WA’s First Class Record from 1892 23 Interstate & International Matches 24 Career Records for WA & WA Combined XI 31 Sheffield Shield 38 Batting Averages 40 Bowling Averages 44 Wicket-Keepers 48 Century Partnerships 49 First Class 57 Century Makers 57 Centuries at Each Venue 61 Centuries 62 Outstanding Bowling Performances 67 Five Wickets or More in an Innings 70 Domestic One Day 73 One Day Records 76 Domestic Twenty20 82 Western Warriors 82 Perth Scorchers Big Bash League 84 Combined Domestic T20 Career Records 87 Women's National Cricket League 89 WNCL Career Records 91 Women's Twenty20 93 WT20 Career Records 93 Perth Scorchers Women's Big Bash League 95 WBBL Career Records 96 Combined WT20 & WBBL Career Records 97 These statistics have been updated by Karl Shunker and Patrick Henning. PREMIER CRICKET 98 The WACA also thanks WA Cricket Historian Bill Reynolds for his contribution. First Grade Aggregates, Averages & Awards 100 Premier Cricket 104 Cover: -

Conditions Could Favour Sri Lanka in Series Decider

Saturday 9th July, 2011 Karunaratne to make debut Hettiarachchi receives Presidential pardon Sri Lanka’s rugby scene was Kaluarachchi denied having Conditions could favour a buzz with the news that rugby any knowledge of Hettiarachchi player Nuwan Hettiarachchi receiving a pardon. had received a Pardon from SLRFU Secretary Lasitha President Mahinda Rajapakse. Guneratne too said he knew President’s spokesman nothing about Hettiarachchi Bandula Jayasekere has been receiving a pardon, adding, ‘if Sri Lanka in series decider quoted in stating that the player had received a par- Hettiarachchi had received the don, it has nothing to do with REX CLEMENTINE pardon. rugby’. reporting from Manchester Hettiarachchi was taken into Guneratne said that there Navy custody after officials of was an injunction order issued After being shot out for 174 at Trent Bridge the sea going force protested by the court against on a green top, conditions could favour the Sri that the player had violated a Hettiarachchi and it was valid Lankans here at Old Trafford in Manchester as contract he had with Navy till July 15. Tillakaratne Dilshan searches for his moment of Sports Club and joined another Officials from Kandy SC glory on his first tour as captain of Sri Lanka. team which contests the domes- maintain that Hettiarachchi is The series is leveled at 2-2 with today’s final ODI tic league tournament. their property and should rep- here becoming the decider at Muttiah The Navy SC coach Ronnie resent the Nittawela Club this Muralitharan’s home ground for years where he Ibrahim and manager season. -

Match Report

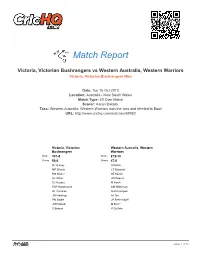

Match Report Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers vs Western Australia, Western Warriors Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers Won Date: Tue 15 Oct 2013 Location: Australia - New South Wales Match Type: 50 Over Match Scorer: Aaron Bakota. Toss: Western Australia, Western Warriors won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/69082 Victoria, Victorian Western Australia, Western Bushrangers Warriors Score 331-8 Score 272-10 Overs 50.0 Overs 47.0 RJ Quiney S Katich MP Stoinis CT Bancroft MS Wade* SE Marsh CL White JW Rogers DJ Hussey M North PSP Handscomb SM Whiteman DT Christian N Rimmington JW Hastings AJ Tye PM Siddle JP Behrendorff JM Holland M Beer* S Boland R Duffield page 1 of 36 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers R B 4's 6's SR RJ Quiney . 4 4 . 1 . 1 4 . 4 2 4 . 1 . 1 1 . 4 . 2 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . // c AJ Tye b AJ Tye 37 37 6 0 100.0 MP Stoinis . 4 . 4 2 . 1 . 1 . 2 1 1 . 1 . run out (CT Bancroft) 63 92 5 2 68.48 2 . 1 . 4 6 . 4 . 1 . 4 . 1 . 1 1 6 . 1 1 . 1 . 5 1 2 1 1 1 1 . // MS Wade* . 4 . 4 . 1 . 1 . 4 2 . 1 1 1 4 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 1 1 4 . 1 lbw b M Beer* 74 82 9 1 90.24 . 1 1 2 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 4 . 1 1 1 . 6 1 1 4 1 1 1 . 2 . // CL White . 4 . 1 . -

Manchester United Lose Patience, Sack Mourinho Tottenham Manager Mauricio AFP Who Played for United

Kohli plays down ‘banter’ as Aussies level series PAGE 16 WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 19, 2018 Lionel Messi collects a record 5th Golden EFL CUP Shoe award as top goalscorer in Europe ARSENAL VS TOTTENHAM Manchester United lose patience, sack Mourinho Tottenham manager Mauricio AFP who played for United. Tot- Pochettino. (REUTERS) MANCHESTER (UK) tenham Hotspur manager Mauricio Pochettino is also MANCHESTER UNITED strongly tipped. Pochettino sacked manager Jose Mour- Mourinho’s reign had start- inho on Tuesday after the ed well enough with the League fits bill as club’s worst start to a season Cup and the Europa League in nearly three decades. trophies but for a club that has new manager, Mourinho, 55, became in- been champions of England 20 creasingly spiky in his last few times, neighbours Manchester says Neville months at Old Trafford, lash- City’s dominance over them in ing out at the board’s transfer the league has hurt. AFP policy and turning his fire on The wound went even LONDON his squad, especially record deeper for Mourinho as City signing Paul Pogba. are managed by Pep Guardi- GARY NEVILLE says Man- His constant complaints ola, who got the better of him chester United should target about the players’ lack of de- when he was in charge at Bar- Mauricio Pochettino as their sire had an impact on the celona and Mourinho was at new manager after sacking pitch, culminating in the 3-1 Real Madrid. Jose Mourinho, describing the defeat by Premier League Despite his protestations Spurs boss as the “ideal candi- leaders Liverpool on Sunday to the contrary, the United date”.