The Sandpapergate Scandal and the Limits of Transnational Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scoresheet NEWSLETTER of the AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC

scoresheet NEWSLETTER OF THE AUSTRALIAN CRICKET SOCIETY INC. www.australiancricketsociety.com.au Volume 38 / Number 2 /AUTUMN 2017 Patron: Ricky Ponting AO WINTER NOSTALGIA LUNCHEON: Featuring THE GREAT MERV HUGHES Friday, 30 June, 2017, 12 noon for a 12.25 start, The Kelvin Club, Melbourne Place (off Russell Street), CBD. COST: $75 – members & members’ partners; $85 – non-members. TO GUARANTEE YOUR PLACE: Bookings are essential. This event will sell out. Bookings and moneys need to be in the hands of the Society’s Treasurer, Brian Tooth at P.O. Box 435, Doncaster Heights, Vic. 3109 by no later than Tuesday, 27 June, 2017. Cheques should be made payable to the Australian Cricket Society. Payment by electronic transfer please to ACS: BSB 633-000 Acc. No. 143226314. Please record your name and the names of any ong-time ACS ambassadors Merv Hughes is guest of honour at our annual winter nostalgia luncheon at the guests for whom you are Kelvin Club on Friday, June 30. Do join us for an entertaining afternoon of reminiscing, story-telling and paying. Please label your Lhilariously good fun – what a way to end the financial year! payment MERV followed by your surname – e.g. Merv remains one of the foremost personalities in Australian cricket. His record of four wickets per Test match and – MERVMANNING. 212 wickets in all Tests remains a tribute to his skill, tenacity and longevity. Standing 6ft 4in in the old measure Brian’s phone number for Merv still has his bristling handle-bar moustache and is a crowd favourite with rare people skills. -

Indian Premier League 2019

VVS LAXMAN Published 3.4.19 The last ten days have reiterated just how significant a place the Indian Premier League has carved for itself on the cricke�ng landscape. Spectacular ac�on and stunning performances have brought the tournament to life right from the beginning, and I expect the next six weeks to be no less gripping. From our point of view, I am delighted at how well Hyderabad have bounced back from defeat in our opening match, against Kolkata. Even in that game, we were in control �ll the end of the 17th over of the chase, but Andre Russell took it away from us with brilliant ball-striking. Even though I was in the opposi�on dugout, I couldn’t help but marvel at how he snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. The beauty of our franchise is that the shoulders never droop, the heads never drop. There is too much experience, quality and class among the playing group for that to happen. As members of the support staff, our endeavour is to keep the players in a good mental space. But eventually, it is the players who have to deliver on the park, and that’s what they have done in the last two games. David Warner has been outstanding. There is li�le sign that he has been out of interna�onal cricket for a year. His work ethics are exemplary, and I can see the hunger and desire in his eyes. He is striking the ball as beau�fully as ever, and there is a calmness about him that is infec�ous. -

P14 5 Layout 1

14 Established 1961 Sports Tuesday, March 27, 2018 Australian cricket faces huge backlash over ball-tampering Cricket Australia chief Sutherland rushing to S Africa SYDNEY: Sutherland was rushing to South Africa yes- Monday. “We know Australians want answers and we terday with the sport facing one of the toughest weeks will keep you updated on our findings and next steps, as in its history as a backlash grows over a ball-tampering a matter of urgency.” Smith and all members of the team scandal which is likely to cost Steve Smith the Test cap- will remain in South Africa to assist in the probe to taincy. Sponsors expressed “deep concern” as media determine exactly what happened, and who knew. and fans called for wide- Smith, whose talents with the spread changes and deci- bat have drawn breathless sive action following the comparisons with Aussie great shock admission that Smith Don Bradman, is not the only and senior team members man caught in the crosshairs. plotted to cheat in South Sponsors David Warner also stood Africa. Smith, 28, was down from his role as vice- removed from the captain- expressed captain, while questions remain cy for the remainder of the over coach Darren Lehmann third Test against South ‘deep concern’ although Smith said the former Africa on Sunday and was Australian international was not then banned for one match involved in the conspiracy. by the International Cricket Smith initially said the deci- Council (ICC). sion was made by the leader- His team’s weekend of ship group within the team, but shame then ended in a crushing 322-run rout. -

STATISTICS 2019-20 Meg Lanning CONTENTS

WACA STATISTICS 2019-20 Meg Lanning CONTENTS Ground Records 2 International Records for WA Players 4 Domestic Records for WA Players 5 Laurie Sawle Medal & Zoë Goss Medal Winners 7 INTERNATIONAL 8 Players selected from Western Australia to represent Australia in Test Matches and Touring Teams 8 Test Match Records for WA Players 15 One Day International Records for WA Players 17 Twenty20 International Records for WA Players 19 Test Match Records for WA Female Players 20 One Day International Records for WA Female Players 21 Twenty20 International Records for WA Female Players 22 DOMESTIC 23 WA’s First Class Record from 1892 23 Interstate & International Matches 24 Career Records for WA & WA Combined XI 31 Sheffield Shield 38 Batting Averages 40 Bowling Averages 44 Wicket-Keepers 48 Century Partnerships 49 First Class 57 Century Makers 57 Centuries at Each Venue 61 Centuries 62 Outstanding Bowling Performances 67 Five Wickets or More in an Innings 70 Domestic One Day 73 One Day Records 76 Domestic Twenty20 82 Western Warriors 82 Perth Scorchers Big Bash League 84 Combined Domestic T20 Career Records 87 Women's National Cricket League 89 WNCL Career Records 91 Women's Twenty20 93 WT20 Career Records 93 Perth Scorchers Women's Big Bash League 95 WBBL Career Records 96 Combined WT20 & WBBL Career Records 97 These statistics have been updated by Karl Shunker and Patrick Henning. PREMIER CRICKET 98 The WACA also thanks WA Cricket Historian Bill Reynolds for his contribution. First Grade Aggregates, Averages & Awards 100 Premier Cricket 104 Cover: -

The Temptations of Ball Tampering: Steve Smith's Australian Team

The Temptations of Ball Tampering: Steve Smith’s Australian Team in South Africa By Dr. Binoy Kampmark Theme: History Asia-Pacific Research, March 25, 2018 There was an audacity about it, carried out with amateurish callowness. As it turned out Australian batsman Cameron Bancroft, besieged and vulnerable, had been egged on by Australian cricket captain Steve Smith and the Australian leadership to do the insufferable: tamper with the ball. Before the remorseless eagle eyes of modern cameras, Bancroft, in the third Test against South Africa in Cape Town, was detected possessing yellow adhesive tape intended to pick up dirt and particles that would, in turn, be used on the ball’s surface. This, it was assumed, was intended to give Smith’s team an advantage over an increasingly dominantSouth Africa. The reaction from the head of Cricket Australia, John Sutherland, was one of distress. “It’s a sad day for Australian cricket.” Australian veteran cricketers effused horror and disbelief. Former captainMichael Clarke wished this was “a bad dream”. One of the greatest purveyors of slow bowling in the game’s history,Shane Warne, expressed extreme disappointment “with the pictures I saw on our coverage here in Cape Town. If proven the alleged ball tampering is what we all think it is – then I hope Steve Smith (Captain) [and] Darren Lehmann (Coach) do the press conference to clean this mess up!” Indignation, not to mention moral and ethical shock, should be more qualified. This, after all, is a murky area of cricket. An injunction against ball tampering may well be enforced but players have been engaged in affecting the shape and constitution of that red cherry since the game took hold on the English greens. -

The Annual Report on the Most Valuable and Strongest IPL Brands December 2019 About Brand Finance

IPL 2019 The annual report on the most valuable and strongest IPL brands December 2019 About Brand Finance. Contents. Brand Finance is the world’s leading independent About Brand Finance 2 brand valuation consultancy. Get in Touch 2 Brand Finance was set up in 1996 with the aim of ‘bridging the gap between marketing and finance’. For Request Your Brand Value Report 4 more than 20 years, we have helped companies and organisations of all types to connect their brands to the Brand Valuation Methodology 5 bottom line. Foreword 6 We pride ourselves on four key strengths: Executive Summary 8 + Independence + Transparency + Technical Credibility + Expertise Picture TBD 15 We put thousands of the world’s biggest brands to the Definitions 16 test every year, evaluating which are the strongest and most valuable. Sponsorship Services 18 Brand Finance helped craft the internationally Sports Services 19 recognised standard on Brand Valuation – ISO 10668, and the recently approved standard on Brand Communications Services 20 Evaluation – ISO 20671. Brand Finance Network 22 Get in Touch. For business enquiries, please contact: Savio D'Souza Director [email protected] For media enquiries, please contact: Sehr Sarwar BrandirectoryGlobal Forum 2019 Communications Director [email protected] For all other enquiries, please contact: Understanding the Value of [email protected] Geographic Branding +44 (0)207 389 9400 The world's largest 2 April 2019 brand value database. For more information, please visit our website: www.brandfinance.com Join us at the Brand Finance Global Forum, anVisit action-packed to see all day-long Brand event Finance at the Royal rankings,Automobile Club reports, in London, and as wewhitepapers explore how linkedin.com/company/brand-finance geographic branding can impact brand value, attract customers, and infl uence key stakeholders.published since 2007. -

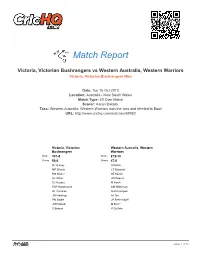

Match Report

Match Report Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers vs Western Australia, Western Warriors Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers Won Date: Tue 15 Oct 2013 Location: Australia - New South Wales Match Type: 50 Over Match Scorer: Aaron Bakota. Toss: Western Australia, Western Warriors won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/69082 Victoria, Victorian Western Australia, Western Bushrangers Warriors Score 331-8 Score 272-10 Overs 50.0 Overs 47.0 RJ Quiney S Katich MP Stoinis CT Bancroft MS Wade* SE Marsh CL White JW Rogers DJ Hussey M North PSP Handscomb SM Whiteman DT Christian N Rimmington JW Hastings AJ Tye PM Siddle JP Behrendorff JM Holland M Beer* S Boland R Duffield page 1 of 36 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Victoria, Victorian Bushrangers R B 4's 6's SR RJ Quiney . 4 4 . 1 . 1 4 . 4 2 4 . 1 . 1 1 . 4 . 2 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . // c AJ Tye b AJ Tye 37 37 6 0 100.0 MP Stoinis . 4 . 4 2 . 1 . 1 . 2 1 1 . 1 . run out (CT Bancroft) 63 92 5 2 68.48 2 . 1 . 4 6 . 4 . 1 . 4 . 1 . 1 1 6 . 1 1 . 1 . 5 1 2 1 1 1 1 . // MS Wade* . 4 . 4 . 1 . 1 . 4 2 . 1 1 1 4 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 1 1 4 . 1 lbw b M Beer* 74 82 9 1 90.24 . 1 1 2 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 . 4 . 4 . 1 1 1 . 6 1 1 4 1 1 1 . 2 . // CL White . 4 . 1 . -

INFORMATION and Tools

Community Cricket Contacts Facility Guidelines Cricket ACT 02 6239 6002 Is a document that details cricket’s recommendations, requirements and resources for the provision, improvement Cricket NSW 02 8302 6000 and enhancement of community cricket environments across Australia. INFORMATION To find out more go to Cricket Tasmania 03 6282 0400 community.cricket.com.au/clubs/facility-guidelines Queensland Cricket 07 3292 3100 AND tools PlayCricket for Clubs & Associations The purpose of PlayCricket is to assist with Cricket Victoria 03 9653 1100 informing parents & prospective players on the various cricket programs and formats available to them. PlayCricket allows them to search for Northern Territory Cricket 08 8944 8900 programs and Clubs in their local area. Cricket Australia encourages all Clubs to update their ‘Organisation Details’ in MyCricket admin by logging on to South Australian Cricket Association 08 8300 3800 mycricket.cricket.com.au and ensure: • Club details are correct Western Australian Cricket Association 08 9265 7222 • Your MILO in2CRICKET and MILO T20Blast programs are activated (if applicable) • Online Registrations and Payments are confirmed (if applicable). Cricket Australia National 03 9653 8826 Community Facilities Manager Encourage new and returning players to sign up to your club for the upcoming season. For more information contact the PlayCricket Help Desk on 1800 CRICKET or visit playcricket.com.au Cricket Australia Manager of Club Cricket 03 9653 8861 Promote your club Marketing Collateral To assist Clubs in -

Philpott S. the Politics of Purity: Discourses of Deception and Integrity in Contemporary International Cricket

Philpott S. The politics of purity: discourses of deception and integrity in contemporary international cricket. Third World Quarterly 2018, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1432348. Copyright: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Third World Quarterly on 07/02/2018, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01436597.2018.1432348. DOI link to article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1432348 Date deposited: 23/01/2018 Embargo release date: 07 August 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk 1 The politics of purity: discourses of deception and integrity in contemporary international cricket Introduction: The International Cricket Council (ICC) and civil prosecutions of three Pakistani cricketers and their fixer in October 2011 concluded a saga that had begun in the summer of 2010 with the three ensnared in a spot-fixing sting orchestrated by the News of the World newspaper. The Pakistani captain persuaded two of his bowlers to bowl illegitimate deliveries at precise times of the match while he batted out a specific over without scoring a run. Gamblers with inside knowledge bet profitably on these particular occurrences. This was a watershed moment in international cricket that saw corrupt players swiftly exposed unlike the earlier conviction of the former and now deceased South African captain Hansie Cronje whose corruption was uncovered much -

Mitch Marsh, the 2018 ICC Under 19 Cricket Their Third Group Game

2017/ 18 HOBART & LAUNCESTON U19 MITCH MARSH PATHWAY 04-06 WA U15 School Team 06/07 Fremantle 1st Grade Debut NATIONALCHAMPS.COM.AU 06-09 WA U17 Team WA U19 Team 09-13 National Performance Squad 2009 WA Debut 2010 Australia U19 World Cup Winning Captain 2011 ODI Debut for Australia T20 Debut for Australia 2014 Test Debut for Australia Premier Club: Fremantle Junior Club: Willetton SUMMER OF INTERNATIONAL CRICKET MAGELLAN ASHES TEST SERIES AUSTRALIA V ENGLAND Thurs 23 - Mon 27 Nov Sat 2 - Wed 6 Dec Thurs 14 – Mon 18 Dec Tues 26 - Sat 30 Dec Thurs 4 - Mon 8 Jan 2018 The Gabba Adelaide Oval The WACA MCG SCG GILLETTE ODI SERIES AUSTRALIA V ENGLAND Sun 14 Jan 2018 Fri 19 Jan 2018 Sun 21 Jan 2018 Fri 26 Jan 2018 Sun 28 Jan 2018 MCG The Gabba SCG Adelaide Oval Perth Stadium GILLETTE T20 INTERNATIONAL AUSTRALIA V NEW ZEALAND AUSTRALIA V ENGLAND AUSTRALIA V ENGLAND Sat 3 Feb 2018 Wed 7 Feb 2018 Sat 10 Feb 2018 SCG Blundstone Arena, Hobart MCG PRIME MINISTER’S XI V ENGLAND T20 | Fri 2 Feb 2018 | Manuka Oval MEN’S INTERNATIONAL MATCHES TICKET PRICES PRIME MINISTER’S XI TICKET PRICES ADULTS* $30 | KIDS *$10 | FAMILY *65 ADULTS* $25 | KIDS *$10 | FAMILY *55 *at match price. Per transaction agency service/delivery fee from $7.05 (men’s matches)/ $5.50 (PM’s XI) applies to other purchases HOW TO PURCHASE TICKETS GROUP BOOKINGS GROUP BOOKINGS (10+) INDIVIDUAL TICKETS (UP TO 9) Book now at cricket.com.au/tickets Visit: cricket.com.au/groups CRICKET AUSTRALIA OFFICIAL HOSPITALITY CRICKET AUSTRALIA TRAVEL OFFICE (MEN’S INTERNATIONAL ONLY) (MEN’S INTERNATIONAL ONLY) Visit: cricketaustralia.com.au/hospitality Visit: www.cricket.com.au/travel SUMMER OF INTERNATIONAL CRICKET On behalf of Cricket Australia, I welcome all athletes, parents and families to this year’s Under 19 National Championships. -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing. -

Sachin Tendulkar SYDNEY: the Australian Players, MUMBAI: Former India Batsman Accept to Those Things," He Said

FRITZ KELLER, German football fed- eration (DFB) president resigned on TUESDAY, SILCHAR Monday after comparing vice presi- 10 MAY 18, 2021 SportChronicle dent Rainer Koch to a Nazi judge. Australians in IPL arrive in Sydney, Dealt with anxiety for 10-12 Nadal outwits Djokovic set to quarantine for two weeks years: Sachin Tendulkar SYDNEY: The Australian players, MUMBAI: Former India batsman accept to those things," he said. coaches and commentary staff and captain Sachin Tendulkar Tendulkar, who is the high- for 10th Rome Open title who were in the 2021 IPL arrived said he had to deal with anxi- est run-scorer of all time in Test in Sydney on Monday from the ety before a match even after and ODI cricket and the only final. Nadal, on the other hand, Maldives and will be in quaran- he had spent several years in cricketer to score 100 interna- TENNIS needed an hour-and-a-half-to tine for 14 days. international cricket. tional centuries, said that he felt AGENCIES take down Reilly Opelka of the The cricketers had gone to "Pressure, anxiety and all the effects of anxiety for about USA. Djokovic, who was bid- the Maldives after the suspen- were always there. In my case, 10-12 years. "Then I started ROME: World No. 3 Spaniard ding to record his first win on sion of the tournament as the I realised all my preparations accepting that it was part of my Rafael Nadal on Sunday won clay against the Spaniard since Australian government had were there in a physical sense.