Volume 12, Number 1 Winter 2021 Contents ARTICLES a Proposal For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superstition, Skill, Or Cheating? How Casinos and Regulators Can Combat Edge Sorting

Volume 24 Issue 1 Article 1 1-1-2017 Superstition, Skill, or Cheating? How Casinos and Regulators Can Combat Edge Sorting Jordan Scot Flynn Hollander Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Gaming Law Commons Recommended Citation Jordan S. Hollander, Superstition, Skill, or Cheating? How Casinos and Regulators Can Combat Edge Sorting, 24 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 1 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol24/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\24-1\VLS101.txt unknown Seq: 1 13-JAN-17 13:39 Hollander: Superstition, Skill, or Cheating? How Casinos and Regulators Can JEFFREY S. MOORAD SPORTS LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XXIV 2017 ISSUE 1 ARTICLE SUPERSTITION, SKILL, OR CHEATING? HOW CASINOS AND REGULATORS CAN COMBAT EDGE SORTING JORDAN SCOT FLYNN HOLLANDER* I. INTRODUCTION Since the advent of gambling activity, people have sought to gain an edge or advantage over the house to increase their chances or odds of winning. From the use of slugs and increasing the amount of a wager after play has begun, to sophisticated teams and technological devices that fool slot machines, people will seemingly stop at nothing to try to overcome the house advantage. One exam- ple is advantage play. -

2013 Indiana State Football Interactive Guide - Gosycamores.Com—Official Web Site of Indiana State Athletics

Football Media Guide 2013 Download date 07/10/2021 08:37:31 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/5358 2013 Indiana State Football Interactive Guide - GoSycamores.com—Official Web Site of Indiana State Athletics Courtesy: Tony Campbell/ISU Photographic Services 2013 Indiana State Football Interactive Guide Courtesy:ISU Athletics Share | Release:08/15/2013 Welcome to the 2013 Indiana State Football Interactive Guide. Below you will find all of the information you need regarding the Sycamore football program. Table Of Contents Information Link 2013 Indiana State Football Roster/Player Bios Link Head Coach Mike Sanford Link 2013 Sycamore Football Coaching Staff Link 2013 Indiana State Football Schedule/Results Link Why I Chose Indiana State Link Memorial Stadium -- Home Of Sycamore Football Link The Indiana State Football Locker Room Link 2012 Season In Review/Final Season Statistics Link 2012 Season In Review/Schedule, Results, Recaps, Stats Link The Record Book Link 2013 Opponent History/Missouri Valley Football Conference Link All-Time Indiana State Football Guides Link Historical Indiana State Football Yearly Statistics (1999-2012) Link Missouri Valley Football Conference Records Link Sycamore Football On Twitter Link Sycamore Football On Facebook Link Football Recruiting Questionnaire Link Back to http://www.gosycamores.com/ViewArticle.dbml?PRINTABLE_PAGE=YES&DB_OEM_ID=15200&ATCLID=209150261[8/22/2013 1:29:08 PM] 2013 Indiana State Football Interactive Guide - GoSycamores.com—Official Web Site of Indiana State Athletics http://www.gosycamores.com/ViewArticle.dbml?PRINTABLE_PAGE=YES&DB_OEM_ID=15200&ATCLID=209150261[8/22/2013 1:29:08 PM] Football - Roster - GoSycamores.com—Official Web Site of Indiana State Athletics Football - 2013 Roster Season 2013-14 Share | Click on arrows to sort by chosen column. -

Communications Big 12 Championship 19-8 12-6 #11 / #12 46-12 32-8 11 Overall Big 12 Ranking (Ap/Coaches) Big 12 Champ

MARCH 11, 2021 | BIG 12 CHAMPIONSHIP - QUARTERFINALS | GAME NOTES KANSAS COMMUNICATIONS BIG 12 CHAMPIONSHIP 19-8 12-6 #11 / #12 46-12 32-8 11 OVERALL BIG 12 RANKING (AP/COACHES) BIG 12 CHAMP. UNDER BILL SELF BIG 12 CHAMP. TITLES AT Bill Self 520-117 (.816) T-Mobile Center 24-5 (.828) JAYHAWKS HEAD COACH RECORD AT KU, 18TH SEASON 2021 VENUE CHAMP. RECORD AT T-MOBILE CENTER GAME SCHEDULE (H: 13-1; A: 4-6; N: 2-1) KANSAS VS OKLAHOMA / IOWA STATE KU-OSU SERIES AT A GLANCE KU OPP Big 12 Championship • Quarterfinals OVERALL KANSAS LEADS, 151-69 Date Rnk Rnk Opponent TV Time/Result Kansas City, Mo. • T-Mobile Center (18,972) in Big 12 Champ. (T-Mobile Center) Tied, 2-2 (0-0) NOVEMBER (1-1) 28 Thursday, March 11, 2020 • 5:30 p.m. (CT) Last Meeting L, 68-75 @ OU, 1/23/21 26 6/52 1/ Gonzaga% FOX L, 90-102 27 6/5 -/- Saint Joseph’s% FS1 W, 94-72 KU-ISU SERIES AT A GLANCE ESPN / ESPN2 JAYHAWK RADIO NETWORK OVERALL KANSAS LEADS, 186-66 DECEMBER (7-0) Play-by-Play: Bob Wischusen Radio: IMG Jayhawk Radio Network in Big 12 Champ. (T-Mobile Center) Tied, 3-3 (1-3) 1 7/5 20/9 Kentucky# ESPN W, 65-62 Analyst: Fran Fraschilla Webcast: KUAthletics.com/Radio Last Meeting W, 64-50 @ ISU, 2/11/21 3 7/5 -/- WASHBURN B12 NOW W, 89-54 Reporter: Holly Rowe Play-by-Play: Brian Hanni Producer: Scott Gustafson Analyst: Greg Gurley RANKINGS 5 7/5 -/- NORTH DAKOTA ST. -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

2009-2010 Colorado Avalanche Media Guide

Qwest_AVS_MediaGuide.pdf 8/3/09 1:12:35 PM UCQRGQRFCDDGAG?J GEF³NCCB LRCPLCR PMTGBCPMDRFC Colorado MJMP?BMT?J?LAFCÍ Upgrade your speed. CUG@CP³NRGA?QR LRCPLCRDPMKUCQR®. Available only in select areas Choice of connection speeds up to: C M Y For always-on Internet households, wide-load CM Mbps data transfers and multi-HD video downloads. MY CY CMY For HD movies, video chat, content sharing K Mbps and frequent multi-tasking. For real-time movie streaming, Mbps gaming and fast music downloads. For basic Internet browsing, Mbps shopping and e-mail. ���.���.���� qwest.com/avs Qwest Connect: Service not available in all areas. Connection speeds are based on sync rates. Download speeds will be up to 15% lower due to network requirements and may vary for reasons such as customer location, websites accessed, Internet congestion and customer equipment. Fiber-optics exists from the neighborhood terminal to the Internet. Speed tiers of 7 Mbps and lower are provided over fiber optics in selected areas only. Requires compatible modem. Subject to additional restrictions and subscriber agreement. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Copyright © 2009 Qwest. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Joe Sakic ...........................................................................2-3 FRANCHISE RECORD BOOK Avalanche Directory ............................................................... 4 All-Time Record ..........................................................134-135 GM’s, Coaches ................................................................. -

Prohibited Athletic Activities Policies and Procedures

NCAA Division III Football Prohibited Athletic Activities Policies and Procedures Policies and procedures related to prohibited athletic activity in football shall be established and maintained. Annual Review. The policies and procedures, including the list and definition of prohibited activities, shall be reviewed on an annual basis and prior to the start of preseason football practice for the year. Any addition to the list of prohibited activities or change to the existing definitions of prohibited activities must be reviewed by the NCAA Committee on Competitive Safeguards and Competitive Aspects of Sports and the appropriate divisional football committees (e.g., NCAA Division I Football Oversight Committee, NCAA Division II Football Committee, NCAA Division III Football Committee). Prohibited Athletic Activity. Generally, athletic activity designed to create straight line collisions is not permissible. The prohibition on activity designed to create straight line collisions does not prohibit a team from scrimmaging or conducting a drill with a limited number of players if upon the snap of the ball or a whistle being blown, players are instructed to take angles and to execute offensive and defensive schemes as in game situations. Further, activity that includes the essential elements of the below definitions are also prohibited. However, elements of the below that may occur during thud or live action (e.g., scrimmage) remain permissible. The following athletic activities/drills are not permissible: 1. Bull in the Ring/King of the Circle. Prior to the start of the drill players stand in a circle surrounding one player in the middle. Each player is assigned a number. The drill begins when a coach calls out a number. -

Game Changer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 GAME CHANGER HOW COACH BUDDY TEEVENS ’79 TURNED LOSERS INTO CHAMPIONS—AND TRANSFORMED THE GAME OF FOOTBALL FOREVER FIVE DOLLARS H W’ P B B FINE HANDCRAFTED VERMONT FURNITURE CELEBRATING 4 5 YEARS OF CRAFTSMANSHIP E E L L C C 5 T G, W, VT 802.457.2600 23 S M S, H, NH 603.643.0599 NH @ . . E THETFORD, VT FLAGSHIP SHOWROOM + WORKSHOP • S BURLINGTON, VT • HANOVER, NH • CONCORD, NH NASHUA, NH • BOSTON, MA • NATICK, MA • W HARTFORD, CT • PHILADELPHIA, PA POMPY.COM • 800.841.6671 • We Offer National Delivery S . P . dartmouth_alum_Aug 2018-5.indd 1 7/22/18 10:23 PM Africa’s Wildlife Inland Sea of Japan Imperial Splendors of Russia Journey to Southern Africa Trek to the Summit with Dirk Vandewalle with Steve Ericson with John Kopper with DG Webster of Mt. Kilimanjaro March 17–30, 2019 May 22–June 1, 2019 September 11–20, 2019 October 27–November 11, 2019 with Doug Bolger and Celia Chen ’78 A&S’94 Zimbabwe Family Safari Apulia Ancient Civilizations: Vietnam and Angkor Wat December 7–16, 2019 and Victoria Falls with Ada Cohen Adriatic and Aegean Seas with Mike Mastanduno Faculty TBD June 5–13, 2019 with Ron Lasky November 5–19, 2019 Discover Tasmania March 18–29, 2019 September 15–23, 2019 with John Stomberg Great Journey Tanzania Migration Safari January 8–22, 2020 Caribbean Windward Through Europe Tour du Montblanc with Lisa Adams MED’90 Islands—Le Ponant with John Stomberg with Nancy Marion November 6–17, 2019 Mauritius, Madagascar, with Coach Buddy Teevens ’79 June 7–17, 2019 September 15–26, 2019 -

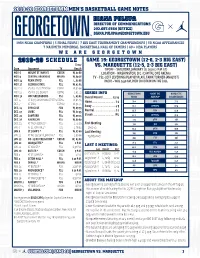

Terrell Allen Joined the Starting Lineup 11 Games Ago and Has Averaged 10.2 Ppg, 5.5 Apg and 1.4 Spg While Shooting 49.4% (39-79) from the Field

2019-20 GEORGETOWN MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS 202.687.6564 (OFFICE) [email protected] 1984 NCAA CHAMPIONS | 5 FINAL FOURS | 7 BIG EAST TOURNAMENT CHAMPIONSHIPS | 30 NCAA APPEARANCES 7 NAISMITH MEMORIAL BASKETBALL HALL OF FAMERS | 60+ NBA PLAYERS WE ARE GEORGETOWN SCHEDULE GAME 19: GEORGETOWN (12-6, 2-3 BIG EAST) Time/ VS. MARQUETTE (12-5, 2-3 BIG EAST) Date Opponent TV Result TIPOFF – SATURDAY, JANUARY 18, 2020 (2 P.M. ET) NOV. 6 MOUNT ST. MARY’S CBSSN W, 81-68 LOCATION – WASHINGTON, D.C. (CAPITAL ONE ARENA) NOV. 9 CENTRAL ARKANSAS MASN2 W, 89-78 TV – FS1 - JEFF LEVERING (PLAY-BY-PLAY), TARIK TURNER (ANALYST) NOV. 14 PENN STATE ! FS1 L, 81-66 RADIO – WOL 1450 AM, RICH CHVOTKIN ON THE CALL NOV. 17 GEORGIA STATE FS1 W, 91-83 NOV. 21 VS. NO. 22/22 TEXAS # ESPN2 W, 82-66 NOV. 22 VS. NO. 1/1 DUKE # ESPN2 L, 81-73 SERIES INFO GEORGETOWN ABOUT THE MARQUETTE NOV. 30 UNC GREENSBORO FS2 L, 65-61 Overall Record ............. 13-14 HOYAS MATCHUP GOLDEN EAGLES DEC. 4 AT RV/25 OKLAHOMA STATE % ESPN+ W, 81-74 Home ................................ 7-4 79.0 PPG 77.2 DEC. 7 AT SMU ESPNU W, 91-74 Away ................................ 4-9 73.1 OPP PPG 67.9 DEC. 14 SYRACUSE FOX W, 89-79 DEC. 17 UMBC FS1 W, 81-55 Neutral ............................. 2-1 45.7 FG% 42.9 DEC. 21 SAMFORD FS1 W, 99-71 Streak .............................. W1 42.1 OPP FG% 38.9 DEC. 28 AMERICAN FS1 W, 80-60 113 3PM 168 DEC. -

Biblioteca Digital De Cartomagia, Ilusionismo Y Prestidigitación

Biblioteca-Videoteca digital, cartomagia, ilusionismo, prestidigitación, juego de azar, Antonio Valero Perea. BIBLIOTECA / VIDEOTECA INDICE DE OBRAS POR TEMAS Adivinanzas-puzzles -- Magia anatómica Arte referido a los naipes -- Magia callejera -- Música -- Magia científica -- Pintura -- Matemagia Biografías de magos, tahúres y jugadores -- Magia cómica Cartomagia -- Magia con animales -- Barajas ordenadas -- Magia de lo extraño -- Cartomagia clásica -- Magia general -- Cartomagia matemática -- Magia infantil -- Cartomagia moderna -- Magia con papel -- Efectos -- Magia de escenario -- Mezclas -- Magia con fuego -- Principios matemáticos de cartomagia -- Magia levitación -- Taller cartomagia -- Magia negra -- Varios cartomagia -- Magia en idioma ruso Casino -- Magia restaurante -- Mezclas casino -- Revistas de magia -- Revistas casinos -- Técnicas escénicas Cerillas -- Teoría mágica Charla y dibujo Malabarismo Criptografía Mentalismo Globoflexia -- Cold reading Juego de azar en general -- Hipnosis -- Catálogos juego de azar -- Mind reading -- Economía del juego de azar -- Pseudohipnosis -- Historia del juego y de los naipes Origami -- Legislación sobre juego de azar Patentes relativas al juego y a la magia -- Legislación Casinos Programación -- Leyes del estado sobre juego Prestidigitación -- Informes sobre juego CNJ -- Anillas -- Informes sobre juego de azar -- Billetes -- Policial -- Bolas -- Ludopatía -- Botellas -- Sistemas de juego -- Cigarrillos -- Sociología del juego de azar -- Cubiletes -- Teoria de juegos -- Cuerdas -- Probabilidad -

Professional Blackjack Stanford Wong Pdf

Professional blackjack stanford wong pdf Continue For the main character of the book, see Stanford Wong Flunks Big-Time. John Ferguson (born 1943), known by the pseudonym Stanford Wong, is the author of Gambling, best known for his book Professional Blackjack, first published in 1975. Wong's Blackjack Analyzer computer program, originally created for personal use, was one of the first parts of the commercially available blackjack chance analysis software. Wong appeared on television several times as a participant in the blackjack tournament or as a gambling expert. He owns Pi Yee Press, which has published books by other gambling authors, including King Yao. Blackjack Wong began playing blackjack in 1964, teaching financial courses at San Francisco State University and earning a doctorate in finance from Stanford University in California. Not content with teaching, Wong agreed to receive a salary of $1 for the last term of school, so as not to attend teacher meetings and to continue his gambling career. The term Wong (v.) or Wonging began to mean a certain technique of advantage in blackjack, which Wong made popular in the 1980s. and then go out again. Wonging is the reason that some casinos have signs on some blackjack tables saying: No Mid-Shoe Entry, meaning that a new player has to wait until just first hand after shuffling to start playing. He reviewed or acted as a consultant to blackjack writers and researchers, including Don Schlesinger and Jan Andersen. Wong is known to have been the main operator of the team's advantage players who targeted casino tournaments including Blackjack, Craps and Video Poker in and around Las Vegas. -

2004 Colorado Football Quick Facts

2004 COLORADO FOOTBALL QUICK FACTS 2004 Schedule time (MT) series 2003 Results (Won 5, Lost 7; 3-5 Big 12 North) S 4 COLORADO STATE tba 55-18-2 A 30 Colorado State (Denver) W 42-35 76,219 S 11 at Washington State (at Seattle) tba 3- 2-0 S 6 UCLA W 16-14 48,584 S 18 NORTH TEXAS tba 0- 0-0 S 13 WASHINGTON STATE L 26-47 48,146 O 2 *at Missouri tba 30-35-3 S 20 at Florida State L 7-47 83,294 O 9 *OKLAHOMA STATE (Homecoming) tba 25-16-1 O 4 *at Baylor L 30-42 23,147 O 16 *IOWA STATE (Family Weekend) tba 45-12-1 O 11 *KANSAS (ot) W 50-47 50,477 O 23 *at Texas A & M tba 4- 1-0 O 18 *at Kansas State L 20-49 51,536 O 30 *TEXAS tba 7- 6-0 O 25 *OKLAHOMA L 20-34 54,215 N 6 *at Kansas tba 39-21-3 N 1 *at Texas Tech L 21-26 52,908 N 13 *KANSAS STATE tba 41-17-1 N 8 *MISSOURI W 21-16 47,722 N 26 *at Nebraska (ABC) 10:00a 16-44-2 N 15 *at Iowa State W 44-10 36,977 D 4 Big 12 Championship (at Kansas City; ABC, 6:00p) N 28 *NEBRASKA L 22-31 53,444 *—Big 12 Conference game; OPEN WEEKS: Sept. 25, Nov. 20. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Head Coach: Gary Barnett (Missouri '69) 2003 Record: 5-7-0 Record at Colorado: 34-28 (five seasons) Big 12: 3-5-0 (t-4th/6, North Division) Career Record: 77-84-2 (14 seasons) Nat’l Rankings: NR Office Telephone: 303/492-5330 Bowl: None Nickname: Buffaloes President: Dr. -

Asia's Richest Poker Tournament, Was a Resounding Success

Genting Hong Kong Limited (Continued into Bermuda with limited liability – Registration No.29337) (formerly known as Star Cruises Limited) PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Asia’s richest poker tournament “Manila Millions” declared a resounding success Hong Kong, 23 April, 2012 – Genting Group is delighted to announce that “Manila Millions”, Asia's richest poker tournament, was a resounding success. The inaugural event held at Resorts World Manila (RWM) on 20 April, “Manila Millions” featured a HK$1 million (USD$129,000) buy-in per player and attracted 31 regional and international poker players, including big names such as Phil Ivey, Tom Dwan, Joe Hachem, John Juanda, Johnny Chan, JC Tran and the Le brothers. Mr. Allan Le, one of the Le brothers, ascended to the top of the pack after numerous hair-raising rounds and clinched the top prize money of US$1.687 million. Mr David Chua, President of Genting Hong Kong & Chairman of Travellers International (RWM), said, “We’re very proud to have ‘Manila Millions’ as the inaugural event of the ‘Genting Poker League’ (GPL). We are also grateful to Asian Poker Tour and Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (PAGCOR) for their strong support in making the event a great success.” He continued, “The GPL aspires to be the premier poker tournament globally. We look forward to extending the GPL to multiple Genting Group-related locations, such as Resorts World Genting (RWG).” Mr. CY Lee, President of Genting Malaysia, said, “We look forward to hosting this group of hot shots at the ‘Highlands Millions’ in RWG this fall.” He further added that the “London Millions” will hopefully be held in the not too distant future.