An Overlooked Interest That Grounds the Abortion Right Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MERENDA-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf

THE CANINE-HUMAN INTERRELATIONSHIP AS A MODEL OF POST-OPPOSITIONALITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MULTICULTURAL WOMEN’S AND GENDER STUDIES IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMEN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MULTICULTURAL WOMEN’S AND GENDER STUDIES COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY KIMBERLY CHRISTINE MERENDA, BGS, MA, MA DENTON, TEXAS MAY 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Kimberly Christine Merenda DEDICATION For Pi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was supported and sustained by the wonderful mentorship, kindness, astonishing proofreading skills, and faith of my dissertation chair Dr. AnaLouise Keating. Dr. Keating believed in me before I knew how to believe in myself. Many, many thanks to my committee members, Dr. Agatha Beins and Dr. Stephen Souris. I appreciate Dr. Beins’ expertise and excellent eye for detail. As an undergraduate Dr. Souris encouraged me to go to graduate school and I will always be grateful for the confidence he had in me. Dr. Cheronda Steele’s calm empathy, her insights and strategies, were instrumental in the process and progress of this project. My sincere thanks to Maurice Alcorn who always read and responded kindly. My warm gratitude goes to Dr. Claire Sahlin for her enduring guidance and compassion and for always making time to listen. My children Sierra, Trinity, and Frankie came of age during the course of this project. I love, love, love my children, and their unwavering support strengthened and cheered me throughout the process of this project. Finally and fundamentally, there are my canine companions Fraction, Pi, Abacus, Lemma, Boolean, Julia, Mandelbrot, and Times. -

Derogatory Discourses of Veganism and the Reproduction of Speciesism in UK 1 National Newspapers Bjos 1348 134..152

The British Journal of Sociology 2011 Volume 62 Issue 1 Vegaphobia: derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK 1 national newspapers bjos_1348 134..152 Matthew Cole and Karen Morgan Abstract This paper critically examines discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers in 2007. In setting parameters for what can and cannot easily be discussed, domi- nant discourses also help frame understanding. Discourses relating to veganism are therefore presented as contravening commonsense, because they fall outside readily understood meat-eating discourses. Newspapers tend to discredit veganism through ridicule, or as being difficult or impossible to maintain in practice. Vegans are variously stereotyped as ascetics, faddists, sentimentalists, or in some cases, hostile extremists. The overall effect is of a derogatory portrayal of vegans and veganism that we interpret as ‘vegaphobia’. We interpret derogatory discourses of veganism in UK national newspapers as evidence of the cultural reproduction of speciesism, through which veganism is dissociated from its connection with debates concerning nonhuman animals’ rights or liberation. This is problematic in three, interrelated, respects. First, it empirically misrepresents the experience of veganism, and thereby marginalizes vegans. Second, it perpetuates a moral injury to omnivorous readers who are not presented with the opportunity to understand veganism and the challenge to speciesism that it contains. Third, and most seri- ously, it obscures and thereby reproduces -

A Search for a Compassionate, Responsible, Respectful, Posthumanist Paradigm

Towards a Vegan Eco-Feminist Critical Care Theory: A Search for A compassionate, responsible, respectful, posthumanist paradigm By Annette Mira McLellan A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in Women and Gender Studies Copyright Annette Mira McLellan, 2014 Approved: Dr. Michele Byers - Supervisor Approved: Dr. Val Marie Johnson - Second Reader Approved: Dr. Wilma van der Veen - External Examiner Submitted: April 25, 2014 Towards a Vegan Ecofeminist Critical Care Theory: A Search for a Compassionate, Responsible, Respectful, Posthumanist Paradigm By Annette Mira McLellan Abstract Anti-speciesist theory is not often taught within the humanities nor has it been present in the Women and Gender Studies programs I have attended. To do research concerning the realities other-than-human beings face an alternative theoretical framework is necessary. This thesis explored multiple theoretical perspectives, from a deconstructive (eco) feminist stance, that attempt to bridge the human/animal divide. The six unsanctioned discourses explored were: 1) Animal Rights theory, 2) Feminist Care/Defense theory, 3) Ecofeminism, 4) Radical Anti-Speciesist theory, 5) Liberationist theory, and 6) Posthumanism. From these theoretical strands, and through an affirmative discourse analysis, an alternative hybrid theory, composed of terminology, concepts and ideas selected from the unsanctioned, was pieced together. From this hybrid theory it will be possible to do future research concerning the lives of animal beings under human despotism. This bricolage offers an alternative and intersectional lens from which to know, see and be in the world. Date Submitted: April 25, 2014 1 Special thanks and acknowledgements… …go to Spazz, Gummo, and Flea who stood (laid, played) by me (and on me), walked with me through these expropriated native lands, brought me up when I was down and who continually remind me of relational possibilities. -

Književni Svjetovi S Etnološkom, Ekološkom I Animalističkom Nišom

Nar. umjet. 43/2, 2006, str. 163-186, S. Marjanić, Književni svjetovi s etnološkom, ekološkom… Izvorni znanstveni članak Primljeno: 26.9.2006. Prihvaćeno: 19.10.2006. UDK 821.163.42.09:39:591.5] SUZANA MARJANIĆ Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku, Zagreb KNJIŽEVNI SVJETOVI S ETNOLOŠKOM, EKOLOŠKOM I ANIMALISTIČKOM NIŠOM Pored toga što članak prati mogući dodir etnologije i ekologije s knji- ževnim svjetovima, a pritom je sintagmom etno/eko književnost moguće razumijevati književna djela koja su inducirana etnološkim, folkloristi- čkim i ekološkim znanstvenim djelima ili njihovim sferama, tragom ekološke književnosti članak razmatra i animalističku i radikalnu ani- malističku književnost. Time je umjesto trijade književnost – povijest – – politika (politička kriza) postavljena ekološka niša (književnost – eko- sfera, ekološka kriza), koja svoju etiku proširuje prema biofilnom okrilju i književnoj ekologiji. Ključne riječi: ekologija, književna ekologija, etnologija, animalistička književnost, prava životinja Jadne su životinje ginule kad je počelo, isto kao i ljudi. Nalazili smo kosture po šumi, cijeli kostur, a jedna noga fali, mina je odbila (Nedžad Haradžić, Bugojno; prema Lasić 2003:269). Propitivanjem dodira etnologije i ekologije s književnim svjetovima moguće je uspostaviti sintagmu etno/eko književnost1 kojom se mogu razumijevati književna djela koja su inducirana etnološkim, folklorističkim i ekološkim znanstvenim djelima ili njihovim sferama, a pritom je tragom ekološke 1 Atribut etno/eko (etno-eko) od devedesetih se godina s iniciranjem glazbenoga žanra world music na našoj glazbenoj sceni pojavljuje u brojnim nazivima manifestacija koje u sebi sadrže poveznicu s etnologijom, određenije, s očuvanjem hrvatske folklorne baštine i ekologijom, a koja je uglavnom u navedenim primjerima, moramo priznati, površinska, antropocentrična ekologija. Spomenimo, primjerice, manifestaciju "Eko-Etno Hrvatska", koja se organizira kao izložba proizvoda i usluga ruralnih područja, a godine 2006. -

Vegetarian Starter Kit You from a Family Every Time Hold in Your Hands Today

inside: Vegetarian recipes tips Starter info Kit everything you need to know to adopt a healthy and compassionate diet the of how story i became vegetarian Chinese, Indian, Thai, and Middle Eastern dishes were vegetarian. I now know that being a vegetarian is as simple as choosing your dinner from a different section of the menu and shopping in a different aisle of the MFA’s Executive Director Nathan Runkle. grocery store. Though the animals were my initial reason for Dear Friend, eliminating meat, dairy and eggs from my diet, the health benefi ts of my I became a vegetarian when I was 11 years old, after choice were soon picking up and taking to heart the content of a piece apparent. Coming of literature very similar to this Vegetarian Starter Kit you from a family every time hold in your hands today. plagued with cancer we eat we Growing up on a small farm off the back country and heart disease, roads of Saint Paris, Ohio, I was surrounded by which drastically cut are making animals since the day I was born. Like most children, short the lives of I grew up with a natural affi nity for animals, and over both my mother and time I developed strong bonds and friendships with grandfather, I was a powerful our family’s dogs and cats with whom we shared our all too familiar with home. the effect diet can choice have on one’s health. However, it wasn’t until later in life that I made the connection between my beloved dog, Sadie, for whom The fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains my diet I would do anything to protect her from abuse and now revolved around made me feel healthier and gave discomfort, and the nameless pigs, cows, and chickens me more energy than ever before. -

The World Peace Diet

THE WORLD PEACE DIET Eating for Spiritual Health and Social Harmony WILL TUTTLE, Ph.D. Lantern Books • New York A Division of Booklight Inc. 2005 Lantern Books One Union Square West, Suite 201 New York, NY 10003 Copyright Will Tuttle, 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of Lantern Books. Printed in the United States of America Cover painting by Madeleine W. Tuttle Cover design by Josh Hooten Extensive quotations have been taken from Slaughterhouse: The Shocking Story of Greed, Neglect, and Inhumane Treatment Inside the U.S. Meat Industry by Gail A. Eisnitz (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1997). Copyright 1997 by The Humane Farming Association. Reprinted with permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tuttle, Will M. The world peace diet: eating for spiritual health and social harmony / Will Tuttle. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-59056-083-3 (alk. paper) 1. Food—Social aspects. 2. Food—Philosophy. 3. Diet—Moral and eth- ical aspects. I. Title. RA601.T88 2005 613.2—dc22 2005013690 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ĺĺ I am grateful to the many people who have helped along the way, contributing their insights and energy to the process of creating this book. My heartfelt appreciation to those who read the manuscript at some stage and offered helpful comments, particularly Judy Carman, Evelyn Casper, Reagan Forest, Lynn Gale, Cheryl Maietta, Laura Remmy, Veda Stram, Beverlie Tuttle, Ed Tuttle, and Madeleine Tuttle. -

A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2012 Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics Joel P. MacClellan University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation MacClellan, Joel P., "Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Joel P. MacClellan entitled "Minding Nature: A Defense of a Sentiocentric Approach to Environmental Ethics." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Philosophy. John Nolt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jon Garthoff, David Reidy, Dan Simberloff Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) MINDING NATURE: A DEFENSE OF A SENTIOCENTRIC APPROACH TO ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Joel Patrick MacClellan August 2012 ii The sedge is wither’d from the lake, And no birds sing. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

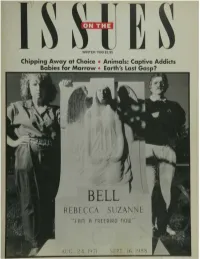

WINTER 1990 $2.95 Chipping Away at Choice • Animals: Captive Addicts Babies for Marrow • Earth's Last Gasp? BELL REBECCA SUZANNE nm fl FREEBIRD now AUG. 24, l()7l SEPT. 16, 1988 Have you seen crack on 42nd Street lately? Or a cat? Or a dog? Or a sheep? and Mental Health Administration NO. Because the addiction problem is a (ADAMHA) spends nearly half a billion dol- uniquely human problem. lars on animal research. They say they are seeking a new "drug" to block the craving So why are federal funding agencies for substances such as cocaine. But many spending millions of your tax dollars on doctors and mental health professionals addiction experiments on animals? These disagree. They think the answer to the drug experiments torture and kill thousands of crisis lies in spending more money on pre- animals each year. And they bring big bucks vention and treatment programs—NOT on to universities. But they do nothing to help animal research. people. In fact, they divert precious tax dollars away from prevention and treatment Please write your federal legislators programs. today, telling them you oppose animal addiction experiments. If you are a medical Right now, there are nearly 10 million or mental health professional, please call addicts in the United States. But there are us NOW for information on other impor- only about 338,000 slots in treatment tant ways you can help people AND centers. animals. Meanwhile, the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, Call FoA at (202) 483-8998. i€S, I want more info on Friends of Animals. Name Friends Address of Animals Friends of Animals, 1623 Connecticut Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20009 THE JOURNAL OF SUBSTANCnE FOR PROGRESSIVE WOMEN VOL. -

The Rights of Animal Persons by David Sztybel, Phd†

The Rights of Animal Persons By David Sztybel, PhD† Abstract: A new analysis in terms of levels of harmful discrimination seems to reveal that the traditional debate between “animal welfare” and animal liberation can more accurately be depicted as animal illfare versus animal liberation. Moreover, there are three main philosophies competing to envision “animal liberation” as an alternative to traditional animal illfare—rights, utilitarianism, and the ethics of care—and it is argued that only animal rights constitutes a reliable bid to secure animal liberation as a general matter. Not only human-centered ethics but also past attempts to articulate animal liberation are argued to have major flaws. A new ethical theory, best caring ethics, is tentatively proposed which features a distinctive alternative to the utilitarian’s commitment to what is best, an emphasis on caring, and an upholding of rights. Finally a series of arguments are sketched in favor of the idea that animals should be deemed persons and it is urged that legal rights for animal persons be legislated. I. Introduction A movement to articulate and advocate “animal liberation” as an alternative to the traditional so-called “animal welfare” paradigm was effectively launched in 1975 with the publication of Animal Liberation by utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer. 1 Since that time, Tom Regan’s The Case for Animal Rights in 1983 was probably the most widely recognized attempt, among many, to articulate a defense of animal interests as based on a strong concept of rights, rather than only considerations of welfare. 2 Starting in the late 1970s, traditional ethical theory, dominated by rights and utilitarianism, came to be criticized by feminists with the suggestion of an alternative: the ethics of care. -

![Beyond Anthropocentrism: Critical Animal Studies and the Political Economy of Communication [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7152/beyond-anthropocentrism-critical-animal-studies-and-the-political-economy-of-communication-1-2537152.webp)

Beyond Anthropocentrism: Critical Animal Studies and the Political Economy of Communication [1]

The Political Economy of Communication 4(2), 54–72 © The Author 2016 http://www.polecom.org Beyond Anthropocentrism: Critical Animal Studies and the Political Economy of Communication [1] Nuria Almiron, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona Keywords: anthropocentrism, speciesism, political economy of communication, ethics Abstract This article argues that the political economy of communication is ready and ethically obliged to expand its moral vision beyond human life, as other disciplines of the social sciences and humanities have already done. Such an expanded moral vision does not mean pushing human suffering to the background, but rather realizing that humans only form part of the planet, and are not above it. Not assigning individuals of other species the same moral consideration we do human beings has no ethical grounding and is actually deeply entangled with our own suffering within capitalist societies – it being particularly connected with human inequality, power relations, and economic interests. Decentering humanity to embrace a truly egalitarian view is the next natural step in a field driven by moral values and concerned with the inequality triggered by power relations. To make this step forward, this article considers the tenets of critical animal studies (CAS), an emerging interdisciplinary field which embraces traditional critical political economy concerns, including hegemonic power and oppression, from a non- anthropocentric moral stance. Critical media and communication scholars are concerned with what prevents human equality and social justice from blossoming. More particularly, they examine the fundamental role media and communication play in preventing or promoting social change. Those scholars devoted to the political economy of communication (PEC) focus upon the structural power relations involved in capitalism or, in Vincent Mosco’s words, in the “power relations that mutually constitute the production, distribution and consumption of resources, including communication resources” (2009: 2). -

Transcript of Chat with David Sztybel on Ar Zone

TRANSCRIPT OF CHAT WITH DAVID SZTYBEL ON AR ZONE January 16, 2011 Carolyn Bailey: ARZone would like to welcome Dr. David Sztybel today, as our Live Chat Guest. David is a Canadian ethicist who specialises in animal ethics. He is a vegan, and has been an animal rights activist for more than 22 years. David has attained his Ph. D. in Philosophy from the University of Toronto (1994-2000) as well as his M.A. in Philosophy from the University of Toronto (1992-94) his B.A. in Philosophy from the University of Toronto (1986-91) and a B. Ed. in English and Social Studies from the University of Toronto (2005-2006) David has published numerous articles pertaining to the liberation of all sentient beings and has lectured at the University of Toronto, Queen's University, and Brock University. David has developed a new theory of animal rights which he terms "best caring," as outlined in "The Rights of Animal Persons.” Criticizing conventional theories of rights, based in intuition, traditionalism or common sense, compassion, Immanuel Kant's theory, John Rawls' theory, and Alan Gewirth's theory, David devises a new theory of rights for human and nonhuman animals. David maintains his blog site at http://davidsztybel.blogspot.com/ and a very informative website at: http://sztybel.tripod.com/home.html David is looking forward to engaging ARZone members today in reference to topics ranging from his literature to his position on animal rights and welfare. Please join with me in welcoming David to ARZone today. Welcome, David! Will: Hello Jason Ward: Good day David!!! Brooke Cameron: Welcome, David! David Sztybel: Hi there, Will and others! Tim Gier: Hello (again) David! Kate: Hello David. -

In the Last Few Decades Both Public and Academic Interest in the Human-Animal Relationship Has Grown. Academically This New Inte

Krisis 2017, Issue 2 2 www.krisis.eu The Theory and Practice of Contemporary Animal Rights Activism a different position, arguing that in some cases animal use is not problematic and Joost Leuven wouldn’t have to be abolished (Donaldson and Kymlicka 2011). Furthermore, some argue that animals deserve to be part of our communities and try to further con- ceptualise what a ‘post-animal liberation’ society would actually look like, asking questions relating to a range of subjects from animal citizenship to human-animal communication (Meijer 2016). Still, while there is much disagreement concerning what animal liberation really ought to mean, most authors seem to agree that we aren’t there yet. While there have been some improvements in the way domesticated animals are being treated, there hasn’t been a fundamental shift in how people relate to these animals. While the numbers of vegetarians might slowly be increasing in western countries, world- wide meat consumption still continues to rise (Donaldson and Kymlicka 2011, 2) and the number of animals whose habitat is being threatened by the continued In the last few decades both public and academic interest in the human-animal expansion of human settlements is still growing (Wadiwel 2009, 283-285). These relationship has grown. Academically this new interest has resulted not only in a figures contribute to the growing awareness within academic and activist circles large body of literature in the fields of animal ethics and political theory, but also that the contemporary animal rights movement might be winning some battles, in the birth of the new interdisciplinary field of human-animal studies.