CHILD PROTECTION COORDINATION WITHIN the CLUSTER APPROACH an Inter‐Agency Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippines: Typhoons

Emergency Appeal no. MDRPH002 PHILIPPINES: TC-2006-000175-PHL 4 December 2006 TYPHOONS The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. In Brief THIS REVISED EMERGENCY APPEAL SEEKS CHF 8,833,789 (USD 7,318,798 OR EUR 5,552,350) IN CASH, KIND, OR SERVICES TO SUPPORT THE PHILIPPINE NATIONAL RED CROSS IN ASSISTING 200,000 BENEFICIARIES FOR NINE MONTHS. Appeal history: · Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) allocated in September: CHF 100,000 (USD 80,000 or EUR 63,291). This DREF will be reimbursed through this Appeal. · Launched on 2 October 2006 for CHF 5,704,261 (USD 4,563,408 or EUR 3,610,292) for three months to assist 126,000 beneficiaries. · Revised 19 October 2006 for CHF 5,704,261 (USD 4,563,408 or EUR 3,610,292) for nine months to assist 126,000 beneficiaries. · 1 December 2006, Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) allocated: An aerial view of the devastation wrought by typhoon Durian. CHF 100,000 (USD 80,000 or EUR 63,291). This appeal re-launch is to take into account the fourth successive typhoon to hit the Philippines within the past two months. The extent of the impact of the latest typhoon, Durian (Reming) is yet to be fully determined. However, initial reports indicate widespread damage caused by the effects of strong wind, rain, floods, mudflow and landslides. A further revision and expansion of the appeal will be undertaken in the coming days based on the assessments of the Philippine National Red Cross (PNRC), the field assessment and coordination team (FACT), the regional disaster response team (RDRT) and the Federation’s country delegation assessment teams currently in the field. -

Appeals: Southeast Asia: Typhoon Chebi - Nov 2006, Consolidated Ap… Appeals Process (CAP): Typhoon Appeal 2006 for Philippines, Appe 05/07/2007 04:02 PM

Appeals: Southeast Asia: Typhoon Chebi - Nov 2006, Consolidated Ap… Appeals Process (CAP): Typhoon Appeal 2006 for Philippines, Appe 05/07/2007 04:02 PM log in | My ReliefWeb | help | Contact Search this section entire site Advanced Search Source: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Print E-mail Save Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Date: 15 Dec 2006 Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP): Typhoon Appeal 2006 for Philippines See all maps for this Emergency 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FIND RELATED Typhoon Impacts DOCUMENTS The Philippines was hit by three extreme weather disturbances (typhoons) in a span By Emergency: of 10 weeks from 25 September to 1 December 2006, then another lower order Southeast Asia: Typhoon typhoon on 9 December. These events triggered landslides, flash floods, mudslides, Chebi - Nov 2006 Southeast Asia: Typhoon widespread flooding and together with the associated high winds, caused Cimaron - Oct 2006 destruction and damage to homes, community buildings, communications, Southeast Asia: Typhoon infrastructure, roads, bridges, agricultural crops and fishing farms. Durian - Dec 2006 Southeast Asia: Typhoon Typhoon Reming (also called Durian), which hit on 30 November, was the most Xangsane - Sep 2006 destructive, severely affecting the provinces of Albay, Catanduanes, and Camarines Sur in southeastern Luzon Island, although significant damage was also recorded in By Country: Philippines Mindoro Oriental, Marinduque, Batangas, Laguna, Mindoro Occidental and Romblon provinces. Most of the severely affected areas are coastal and farming By Source: municipalities and towns located around the periphery of Mt. Mayon Volcano. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Over a thousand lives are estimated to have been lost, and over 180,000 houses Humanitarian Affairs have been totally destroyed by Reming alone. -

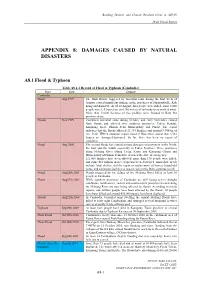

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Quantification of Typhoon-Induced Phytoplankton Blooms Using

remote sensing Article Quantification of Typhoon-Induced Phytoplankton Blooms Using Satellite Multi-Sensor Data Jiayi Pan 1,2,3,* ID , Lei Huang 2, Adam T. Devlin 2 and Hui Lin 2 1 School of Marine Sciences, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China 2 Institute of Space and Earth Information Science, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (A.T.D.); [email protected] (H.L.) 3 Shenzhen Research Institute, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen 518057, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-3943-1308 Received: 19 December 2017; Accepted: 16 February 2018; Published: 20 February 2018 Abstract: Using satellite-based multi-sensor observations, this study investigates Chl-a blooms induced by typhoons in the Northwest Pacific (NWP) and the South China Sea (SCS), and quantifies the blooms via wind-induced mixing and Ekman pumping parameters, as well as pre-typhoon mixed-layer depth (MLD). In the NWP, the Chl-a bloom is more correlated with the Ekman pumping than with the other two parameters, with an R2 value of 0.56. In the SCS, the wind-induced mixing and Ekman pumping have comparable correlations with the Chl-a increase, showing R2 values of 0.4~0.6. However, the MLD exhibits a negative correlation with the Chl-a increase. A multi-parameter quantification model of the Chl-a bloom strength achieves better results than the single-parameter regressions, yielding a more significant R2 value of 0.80, and a lower regression rms of 0.18 mg·m−3 in the SCS, and the R2 value in the NWP is also improved compared with the single-parameter regressions. -

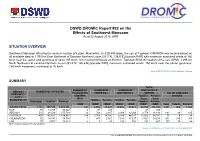

DSWD DROMIC Report #22 on the Effects of Southwest Monsoon As of 22 August 2018, 8PM

DSWD DROMIC Report #22 on the Effects of Southwest Monsoon As of 22 August 2018, 8PM SITUATION OVERVIEW Southwest Monsoon affecting the western section of Luzon. Meanwhile, at 3:00 PM today, the eye of Typhoon CIMARON was located based on all available data at 1,790 km East Northeast of Extreme Northern Luzon (25.7°N, 138.5°E) [outside PAR] with maximum sustained winds of 160 km/h near the center and gustiness of up to 195 km/h. It is moving Northwest at 35 km/h. Typhoon SOULIK location of the eye (3PM): 1,295 km North Northeast of extreme Northern Luzon (31.3°N, 126.6°E) [outside PAR] maximum sustained winds: 150 km/h near the center gustiness: 185 km/h movement: northwest at 25 km/h. Source: DOST-PAGASA Daily Weather Forecast SUMMARY TOTAL NUMBER OF NUMBER OF NUMBER OF DISPLACED & REGION / NUMBER OF AFFECTED EVACUATION INSIDE ECs OUTSIDE ECs SERVED NO. OF DAMAGED PROVINCE / CENTERS Families Persons HOUSES CITY / (ECs) Total Total MUNICIPALITY Families Persons Families Persons Barangays Families Persons Families Persons NOW NOW NOW NOW NOW NOW NOW Total Totally Partially GRAND TOTAL 1,154 399,386 1,609,596 140 5,088 19,328 19,862 95,022 24,950 114,350 1,297 269 1,028 NCR 56 10,006 45,242 4 57 328 - - 57 328 - - - REGION I 515 91,520 375,784 12 769 2,927 3,009 13,209 3,778 16,136 663 48 615 REGION III 456 280,612 1,108,862 114 3,769 14,030 9,194 44,017 12,963 58,047 26 8 18 CALABARZON 52 14,741 68,794 7 488 2,021 7,533 37,217 8,021 39,238 501 195 306 CAR 75 2,507 10,914 3 5 22 126 579 131 601 107 18 89 Note: Ongoing assessment and validation. -

Appendix 3 Selection of Candidate Cities for Demonstration Project

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report APPENDIX 3 SELECTION OF CANDIDATE CITIES FOR DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Table A3-1 Long List Cities (No.1-No.62: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-1 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-2 Long List Cities (No.63-No.124: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-2 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-3 Long List Cities (No.125-No.186: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-3 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-4 Long List Cities (No.187-No.248: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-4 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-5 Long List Cities (No.249-No.310: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-5 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-6 Long List Cities (No.311-No.372: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. -

Philippines Typhoons: Focus on Albay, Catanduanes, And

PHILIPPINES TYPHOONS: Appeal No. MDRPH002 TC-2006-000175-PHL FOCUS ON ALBAY, CATANDUANES, 11 December 2006 AND CAMARINES SUR The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in 185 countries. In Brief · Operations Update no. 01: Period covered: 4 - 11 December 2006; · Appeal target: CHF 8,833,789 (USD 7.3 million or EUR 5.5 million) in cash, kind, or services to support the Philippines National Red Cross with assisting 200,000 Beneficiaries for nine months; · Appeal coverage & contributions: (click here) Operational Summary: Some 100,000 people are currently housed in evacuation centres after 30 November’s Typhoon Durian, which devastated the Bicol region in the Philippines. The Philippines National Red Cross (PNRC) as an auxiliary to the government has played an instrumental role in disaster response, rapidly deploying its large network of experienced well trained volunteers and staff to affected areas. PNRC relief, health and social welfare teams have blanketed affected areas providing a range of services from large scale distributions of food and other relief to evacuation centres. PNRC has also ensured emergency health needs have been met, including the care of a fragile two-day-old baby in Albay. On Tuesday 5 December, the PNRC was joined by the International Federation’s 14-member joint field assessment coordination team (FACT)/South East Asia regional disaster response team (RDRT) to look at longer term community needs, in particular in: shelter (provision of home repair items); water and sanitation; relief; and health. -

Binary Interaction of Typhoons Soulik and Cimaron in 2018 E Part I: Observational Characteristics and Forecast Error

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Tropical Cyclone Research and Review 10 (2021) 32e42 www.keaipublishing.com/tcrr Binary interaction of typhoons Soulik and Cimaron in 2018 e Part I: Observational characteristics and forecast error Eun-Jeong Cha a, Sug-gyeong Yun a, Il-Ju Moon b,*, Dong-Hoon Kim c a Meso-scale Research Team, Convergence Meteorological Research Department, National Institute of Meteorological Sciences, Korea Meteorological Administration, Seogwipo, Republic of Korea b Typhoon Research Center, Jeju National University, Jeju, Republic of Korea c Artificial Intelligence Convergence Research Center, Inha University, Incheon, Republic of Korea Available online 18 March 2021 Abstract To understand structural changes and forecast error, a case study of binary typhoons in the western North Pacific (WNP) of 2018 was investigated using best track and reanalysis data. Soulik was generated on August 16 and Cimaron was generated on August 18, respectively. The 19th typhoon Soulik and 20th typhoon Cimaron co-existed from August 18 to 24 and approached each other. Soulik was located on the western side and Cimaron was located on the eastern side of the WNP. They were located approximately 1300 km from each other at 00 UTC August 22. The Soulik structure began changing around August 22 and became weak and slow, while Cimaron maintained its intensity, size, and moving speed. This observational evidence is likely caused by the binary interaction between two typhoons within a certain distance and environmental steering flow, such as the location of the North Pacific high and strong jet stream of the northern flank of the North Pacific high. -

Philippines : Typhoon Xangsane Annex 1

PHILIPPINES: Appeal No. MDRPH002 01 December 2006 TYPHOON XANGSANE: Glide No. TC-2006- FOCUS ON TYPHOON DURIAN 000175-PHL The Federation’s vision is to strive, through voluntary action, for a world of empowered communities, better able to address human suffering and crises with hope, respect for dignity and a concern for equity. Its mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. In Brief Operations Update no. 1; Appeal target: CHF 5.70 million (USD 4.56 million or EUR 3.61 million); Appeal coverage: 22.2%; Outstanding needs: CHF 4.43 million (USD 3.55 million or EUR 2.81 million); (click here to go directly to the attached Contributions List, also available on the website). Appeal history: • Preliminary appeal launched on 2 October 2006 for CHF 5,704,261 (USD 4,563,408 or EUR 3,610,292) for three months to assist 126,000 beneficiaries. • Revised emergency appeal issued on 19 October 2006 extended the operation timeframe to nine months until July 2007. Final report is therefore due October 2006. • Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) allocated: CHF 100,000 for Typhoon Xangsane in October 2006; additional CHF 100,000 for Typhoon Durian in December 2006 Operational Summary: Even as the Philippines continues to reel from the fury of typhoon Xangsane, Cimaron and Chebi, typhoon Durian battered the country on 30 November 2006. Casualties are far worse this time, with more than 260 reported dead and the full extent of damage still unknown as communication systems are disrupted in the most affected areas. -

Consortium of Non-Traditional Security Studies in Asia ß

ß Consortium of Non-Traditional Security Studies in Asia ß Dec 2006 A Fortnightly Bulletin of Current NTS Issues Confronting Asia Have States heeded the Stern Warning? This section takes a look at the major global players and their reaction to the Stern Review and their efforts in tackling climate change. United Kingdom In light of the Stern Review, there has been increasing pressure on the government from environmental groups – in particular Friends of Earth – and Opposition parties to act on the issue of climate change. UK's main opposition centre-right party, the Conservatives (commonly known as the Tories) have recently suggested plans for a new carbon tax to replace the existing climate change levy. Introduced in 2001 the carbon levy sets limits to the amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted by various industries; similar to the EU’s emissions trading scheme. Moreover, under this scheme companies that stay below these limits can sell spare carbon credits to In this edition:- firms that have overshot their targets. Have States Heeded the Stern Warning? o United Kingdom Tories note, however, that the key problem with the o Australia and the United States climate change levy is that the rates paid by businesses o Europe on their energy use do not reflect the carbon emissions o China from that energy. As such, this does not provide the o India Stern Review’s Suggestions to States right incentives for businesses to switch to low carbon Top and Bottom Ten States Tackling Climate sources of energy. The Carbon Tax aims to rectify this Change by taxing fuel used by businesses in order to Typhoon Durian - Continuing effects of encourage energy efficiency. -

Report for Typhoon

Country Report ( 2007 ) For the 40th Session of the Typhoon Committee ESCAP/WMO Macao, China 21–26 November 2007 People’s Republic of China 1 I. Overview of Meteorological and Hydrological Conditions 1. Meteorological Assessment From Oct. 1st 2006 to Sep. 30th 2007, altogether 23 tropical cyclones (including tropical storms, severe tropical storms, typhoons, severe typhoons and super typhoons) formed over the Western North Pacific and the South China Sea (Fig. 1.1). Among them, 8 TCs formed from Oct. 1st to Dec. 31st in 2006 and 4 of them affected China’s coastal waters but didn’t land on China’s coastal areas. They were super typhoon Cimaron (0619), super typhoon Chebi 0620), super typhoon Durian (0621) and severe typhoon Utor (0622). In 2007, 15 tropical cyclones formed over the Western North Pacific and the South China Sea. The number was obviously less than the average (19.7) during the corresponding period from 1949 to 2006. And 9 of them developed into typhoons or beyond, which accounted for 60.0% of the total. The percentage was higher than the average (58.6%). During the same period, 4 TCs formed over the South China Sea. The number was slightly less than the average (4.7). Moreover, 6 TCs made landfalls over China coastal areas, all of them exceed tropical storm category. They were tropical storm Toraji (0703), severe tropical storm Pabuk 0706), tropical storm Wupit 0707), super typhoon Sepat (0708), super typhoon Wipha 0712) and tropical storm Francisco (0713). The total landed TC number was slightly less than the average (about 6.79), but the percentage of landed TCs (40.0%) was obviously above the average (30.8%). -

Topics Geo Natural Catastrophes 2006 Analyses, Assessments, Positions Topics Geo 2006

Knowledge series Knowledge series Topics Geo Natural catastrophes 2006 Analyses, assessments, positions Topics Geo 2006 Topics © 2007 Münchener Rück Munich Re Group Münchener Rückversicherungs-Gesellschaft Königinstrasse 107 80802 München Germany Order number 302-05217 Contents © 2007 Picture credits Münchener Rückversicherungs-Gesellschaft Cover: Michael Spranger, Hong Kong Königinstrasse 107 Inside front cover: Reuters, Berlin 2 In focus 80802 München pp. 2/3: Reuters, Berlin Germany p. 9: Reuters, Berlin Tel.: +49(89) 38 91-0 pp.10/11: Jan Pitman/Getty Images 5 Lull in the North Atlantic? Fax: +49 (89) 39 90 56 p. 17: picture-alliance/dpa/dpaweb http://www.munichre.com p. 19: Torsten Blackwood/AFP/Getty Images 10 Catastrophe portraits p. 22 left: www.101box.com Supervisory Board p. 22 right: www.jorgent.com Dr. jur. Hans-Jürgen Schinzler (Chairman), p. 23: Ian Hitchcock/Getty Images 13 Winter 2005–2006 in Europe – An exception? Herbert Bach, Hans-Georg Appel, p. 25: Joel Nito/AFP/Getty Images 18 Stormy times down under Holger Emmert, Ulrich Hartmann, p. 29: Michael Spranger, Hong Kong Dr. rer. nat. Rainer Janßen, p. 30 left, right: Michael Spranger, Hong Kong 24 2006 typhoon season in the Northwest Pacific Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Henning Kagermann, p. 33: Reuters, Berlin 28 The Yogyakarta earthquake Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Drs. h. c. mult. Hubert Markl, p. 35 top, bottom: Reuters, Berlin 32 Tsunami strikes Java Wolfgang Mayrhuber, Kerstin Michl, pp. 36/37: Reuters, Berlin Cover: Prof. Karel Van Miert, Ingrid Müller, p. 41: Thomas Loster, Munich In the early hours of 27 May 2006, the densely Prof.