United States Policy Toward Guatemala an Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enkaz Devralmak 2

ENKAZ DEVRALMAK 2. ÖZET KİTAP Bu özet, III Bölüm ve 27 Alt Bölümden oluşan 1. ENKAZ DEVRALMAK özet kitabının devamıdır. BÖLÜM IV “Şu Palyaçoları Başından At” Nixon ve Ford Yönetimleri Döneminde CIA 1968 – 1976 28. “O Palyaçolar Orada Ne Yapıyor?” Helms 1968 baharında, tepesine dikilecek yeni patronun, ya Robert Kennedy, ya da Richard Nixon olacağından korkuyordu. Kennedy, teşkilâtın gücünü istismar etmiş, Helms’e de gayet soğuk ve aşağılayıcı tavırlar almıştı. Başkan adayı olur, sonra da seçilip Başkomutan kisvesini de kuşanırsa, teşkilâtın kendisi hakkındaki gizli dosyalarının tehdidini ensesinde hissedecekti. R. Kennedy seçim kampanyası sırasında bir suikasta kurban gitti. Helms, bu cinayete çok şaşırmış ama fazla da üzülmemişti doğrusu. Richard Nixon ise başka türlü bir sorundu. CIA’nın bir yığın tatlı su elitistleri, Kennedy’nin adamları ve dedikoducular ile dolu olduğunu düşünürdü. John Kennedy ile girişip kıl payı kaybettiği seçim yarışı sırasında yaşanan o meşhur TV tartışmasında yediği gollerin paslarını da rakibine, CIA’nın verdiğine inanıyordu. Nixon, eğer o seçimleri kazansaydı, gizli operasyonları yürütmek için CIA dışında bir örgüt kuracağını 1962’de kaleme aldığı hatıralarında (Six Crisis – Altı Kriz) yazmıştı. CIA’nın yüreğini sökeceğini belirtiyordu açıkça. Helms ve Nixon ilk kez 1968 Ağustos’unda, Başkan Johnson’un çiftliğindeki bir yemek sırasında uzun uzadıya konuştular. Nixon Helms’e, K. Vietnamlıların ABD’yi yendiklerine ilişkin düşüncelerinin sürüp sürmediğini sordu. Helms, düşmanın Dien Bien Phu zaferinden beri bu düşüncede olduğunu söyledi. Nixon’un duymak istediği son şeydi bu. Nixon, seçimleri kazandıktan sonra Johnson’a Helms hakkındaki düşüncelerini sordu, onu görevinde tutmalı mıydı? “Yetenekli ve sadık bir adamdır” dedi Johnson, “Ben olsam tutardım”. Helms yakında bu sadakatinin faturasının ne olduğunu öğrenecekti. -

Commencement 1961-1970

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIMORE, MARYLAND Conferring of Degrees at the close of the eighty-sixth academic year JUNE 12, 1962 Keyser Quadrangle Homewood ORDER OF PROCESSION The Graduates Marshals Carpenter Edgar A. | whs H. J. Johnson Alphonse Chapanis Richard J. Kok.es Carl F. Christ James L. Kuethe Stanley Corrsin Alvin Nason Palmer Futcher Peter E. Wagner John W. Gryder Charles M. Wylie * The Faculties Marshals James W. Poultney and John Walton * The Deans, The Trustees and Honored Guests Marshals Nathan Edelman and M. Gordon Wolman * The Chaplain The Presentors of the Honorary Degree Candidate The Candidates The Commencement Speaker The Chairman of the Board of Trustees The President of the University Chief Marshal Donald H. Andrews Assistant Marshal Francis H. Clauser * For the Presentation of Diplomas Marshals Maurice J. Bessman Stewart H. Hulse, Jr. William H. Huggins W. Kelso Morrill The ushers are undergraduate students of The Johns Hopkins University ORDER OF EVENTS Milton Stover Eisenhower, President of the University, presiding PROCESSIONAL MARCHE SOLENNELLE — FELIX BOROWSKI John H. Elterman, Organist The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing until after the Invocation and the singing of the National Anthem. INVOCATION The Right Reverend Noble C. Powell * THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER THE UNIVERSITY ODE * GREETINGS TO PARENTS CHARLES S. GARLAND Chairman of the Board of Trustees * CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES WILLIAM BENNETT KOUWENHOVEN Presented by Ferdinand Hamburger, Jr. JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON Presented by Francis H. Clauser * ADDRESS JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology ORDER OF EVENTS Continued CONFERRING OF DEGREES ON CANDIDATES Presented by Dean G. -

2016-2017 Year in Review

HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS PAST YEAR SPONSORS 2016-2017 Membership Premier Education Partner • The Council has more than 900 members, of whom half are at the Premier level. Platinum Sponsors ($20,000+) • Magellan Society membership (ages 21-40) includes more than 50 members. Gold Sponsors ($10,000+) Magellan Society Association of Corporate Counsel Jacksonville University North Florida Chapter The Mackowski Family Council Leaders connected with Young Professionals • Brunet-García Foundation - Dick and throughout the year via monthly Luncheon Ladders Coastal Construction Products, Marty Jones to discuss professional and international interests. Inc. - William and Barbara Harrell Mayo Clinic Additionally, Board members were paired one-on-one EverBank Pet Paradise with a selected cohort for the Mentor Program. FIS Gary and Nancy Chartrand • Quarterly Saloon collaborations with the Jacksonville The Haskell Company Advised Fund Public Library and the Jacksonville Zoo connected Holland & Knight LLP Paul and Nina Goodwin community issues within a global context and Holmes Private Client Group - David and Elaine Strickland featured experts in the fields of technology and Marty Jones wildlife conservation. Silver Sponsors ($5,000+) 2016 WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL EXPENSES* Adecco Group North America Bob and Sandy Cook Speaker Program CFA Society of Jacksonville Robert and Sallie Ann Hart 70% Management Chase Admiral and Mrs. Jonathan T. and General Chubb Personal Risk Services Howe Education Program Foley & Lardner LLP Diane DeMell Jacobsen 16% TOTAL EXPENSES: JAX Chamber Randy and Becky Johnson $815,417 McGuireWoods LLP Chuck and Nicki Moorer 14% Regency Centers Russell and Joannie Newton Retina Associates, P.A. -Fred Peter Rummell Lambrou, M.D. and Pat Fred and Susan Schantz 2016 WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL REVENUE Andrews Jay and Deannie Stein AND SUPPORT* US Assure Foundation Trust Sponsorships U.S. -

The Foreign Service Journal, May 1979

tfTNING A/j- BRE . DAMAGE LIABILITY . TRANSIT/WAR INJURY BODILY RISKS . PROPERTY DAMAGE If, for any reason, you plan to live abroad for awhile—think travel-pak. Travel-pak will cover the household and FIRE personal possessions you take with you—on the . way—while there (including storage if desired) and back again. DAMAGE Travel-pak also includes personal liability coverage providing financial protection against those occurrences for which you might become liable. LUGGAGE When you plan to live abroad for awhile— think travel-pak. LIABILITY Return the coupon below for complete details —or call if you’re in a hurry! And when you return to the Washington area —call us—we’ll be happy to help you set up a STOLEN sound, economical insurance program covering your home, auto and life. ■ s SEND FOR DETAILS-TODAY 21A | Tell me about TRAVEL-PAK. WHEN YOU'RE GOING TO LIVE ABROAD! James W. Barrett Company, Inc. Name REED SHAW STENHOUSE INC. OF WASHINGTON, D.C. Insurance Brokers Address w 1140 Connecticut Ave., N.W. Washington. D.C. 20036 Telephone: 202-296-6440 City State Zip A REED SHAW STENHOUSE COMPANY FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL American Foreign Service Association MAY 1979: Volume 56, No. 5 Officers and Members of the Governing Board ISSN 0015-7279 LARS HYDLE, President KENNETH N. ROGERS, Vice President THOMAS O'CONNOR, Second Vice President FRANK CUMMINS, Secretary M. JAMES WILKINSON. Treasurer RONALD L. NICHOLSON, AID Representative PETER WOLCOTT, ICA Representative Communication re: JOSEPH N. MCBRIDE, BARBARA K. BODINE, Immigration Policy ROBERT H. STERN, State Representatives EUGENE M. BRADERMAN & ROBERT G. -

Message to the Senate Transmitting 1987 Partial Revision of the Radio Regulations May 12, 1992

May 12 / Administration of George Bush, 1992 Message to the Senate Transmitting 1987 Partial Revision of the Radio Regulations May 12, 1992 To the Senate of the United States: States submitted two reservations and re- With a view to receiving the advice and sponded to a statement submitted by Cuba consent of the Senate to ratification, I trans- directed at U.S. use of radio frequencies mit herewith the Partial Revision of the in Guantanamo. The specific reservations Radio Regulations (Geneva, 1979) signed on and statement are addressed in the report behalf of the United States at Geneva on of the Department of State. October 17, 1987, and the United States Most of the Partial Revision of the Radio reservations and statement as contained in Regulations entered into force October 3, the Final Protocol. I transmit also, for the 1989, for governments that, by that date, information of the Senate, the report of the had notified the Secretary General of the Department of State with respect to the International Telecommunication Union of 1987 Partial Revision. their approval thereof; provisions specifically The 1987 Revision constitutes a partial re- related to the maritime mobile service in vision of the Radio Regulations (Geneva the high frequency bands entered into force 1979), to which the United States is a party. on July 1, 1991. The primary purpose of the present revision I believe that the United States should, is to update the existing regulations pertain- subject to the reservations mentioned ing to the mobile radio services to take into above, become a party to the 1987 Partial account technical advances and the rapid Revision, which has the potential to improve growth of these services, and to implement mobile radio-communications worldwide. -

Interview with Stephen F. Dachi

Library of Congress Interview with Stephen F. Dachi The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History ProjectInformation Series STEPHEN F. DACHI Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 30, 1997 Copyright 2001 ADST Q: Today is May 30, 1997. This is an interview with Stephen F. Dachi. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. To begin at the beginning, could you tell me when and where you werborn and something about your family? DACHI: I was born in 1933 in Hungary. My father was a dentist. My mother was a physician. They both died when I was three years old in 1936, before the war. My grandparents “inherited me.” They happened to live in Romania. So, I went there just before the Germans marched into Austria, which is my first memory of arriving in Timisoara to live with my grandparents. Then I spent World War II there with them trying to survive. After the war, in 1948, an uncle and aunt who had gone to Canada before the war brought me out there. Q: During the war, what went on then in Romania, particularly as a Hungarian? There was a massive change of borders and everything else at that time. Did you get caught in that? Interview with Stephen F. Dachi http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000263 Library of Congress DACHI: Very definitely, both that and the Holocaust. It has always been hell for Hungarians living in Romania. Kids would curse and harass us if they overheard us speaking Hungarian in the street. -

Archival Supp

It is most important that correspondence to a Foreign Service post be addressed to a section or position rather than to an •officer by. name. This will eliminate delays resulting from the forwarding of official mail to officers who have transferred. Normally,correspondence concerning commercial matteraahould'be addressed. simply "Commercial Section" followed by the name and correct mailing address ofthe post, (Samples of correct mailing addresses appear on page vii.) DEPARTMENT OF STATE Publication 7877 Revised January 1990 OFFICE OF INFORMATION SERVICES Publishing Services Division TO SUBMIT KEY OFFICER CHANGES ONLY: SEND CABLE OR MEMO TO: PS/GE, ROOM 1845, DEPARTMENT OF STATE 20520-1853 ....I,.1.'""w.&. WO,"".., YY.L'"".L.L...... .L ,"".L.Ll;;i.L.L ,",Vu......."'.L .J V.L a."'O.L6.L.LJ..L.L~.L"''''e UP~""'.La.J.J.""1,J.J.6 1,J.J. v.u. export promotion, Commercial Officers assist American business through: arranging appointments with local business and govern ment officials, providing counsel on local trade regulations, laws, and customs; identifying importers, buyers, agents, distributors, and joint venture partners for U.S. firms; and other business assistance. At smaller posts, U.S. commercial interests are represented by Economic/Commercial Officers who also have economic respon sibilities. Financial Attaches analyze and report on major financial devel opments and their implications for U.S. policies and programs. Political Officers analyze and report on political developments and their potential impact on U.S. interests. Labor Officers follow the activities oflabor organizations and can supply information on wages, nonwage costs, social security regulations, labor attitudes toward American investments, etc. -

Notes on Ignatius Global Issues Evening Presentation January 10, 2012 “How Secure Is Our National Security: Where Are the Threats?”

Notes on Ignatius Global Issues Evening Presentation January 10, 2012 “How Secure Is Our National Security: Where Are The Threats?” 1. Opening segment on Republican primary field (in context of it being New Hampshire primary evening). 2. A brief set of comments on how he would expect the President to tout his administration’s foreign policy/defense achievements in the 2012 election: --Has been the most active in effective counterterrorism and strong covert action although covert action will be difficult to talk about. He commented negatively about candidates promising use of covert action. “What is it about ‘covert’ that they don’t understand?” --Has reversed a previous trend of negative views of U.S. around the world --Followed through on exit from Iraq although outcome without U.S. troop presence is worrisome and uncertain. Kurdistan (in the north) is going its own way and doing fine. --Plan for Afghanistan (although Ignatius does not feel that the strategy there has been an effective one and it is not clear that the exit planned will be an easy one) --Afghanistan, he noted, is of importance to the U.S. only because of bordering Pakistan and its proximity to Pak nuclear weapons, the security of which is of paramount concern --Success claimed in Libya 3. National security threat highlights --Iran. Economic sanctions are working and are likely to be intensified (particularly related to pushing other countries to not buy Iranian oil). Iran is feeling the pressure and is operating wildly and erratically. He quoted Harvard Kennedy School professor, Graham Allison as saying that Iran is “the ‘Cuban Missile Crisis’ in slow motion.” Although there is no enthusiasm in the Administration for war with Iran, it is likely there will be some sort of confrontation sometime—just unclear when. -

A Conversation with Ambassador Ryan Crocker” Moderated by Ambassador Marilyn Mcafee

Ambassador Ryan Crocker Notes on Remarks March 19, 2013 The River Club “A Conversation with Ambassador Ryan Crocker” Moderated by Ambassador Marilyn McAfee Q. An Ambassador’s “tool box” is very limited. What did you find most effective and useful in accomplishing your objectives? The most important asset is personal relationships. In the State Department funding is very limited. An ambassador needs to look for funds from other better financed agencies that comprise the Country Team. USAID and the military are two good sources. The military particularly appreciates ideas for good projects. They can do things quickly. Q. As U.S. Ambassador you are the President’s personal representative, but you report to the Secretary of State and as was the case in Iraq and Afghanistan, you have a large in- country U.S. military presence with a four-star (general) in charge. How do you make that work?” We had joint satellite conferences with the key players in Washington so we were always on the same page and decisions once made were clear. It’s a lot harder to coordinate and get decisions at the middle level. At the top it’s easy. The President decides and that’s it. It worked that way with two Presidents. Q. The recent issue of Foreign Policy refers to “militarized foreign policy”. What is the best model? There is the Afghanistan and Iraq model with U.S. troops on the ground, then Libya with U.S. arms, air power and no troops and now Syria and Mali where we are reluctant to get involved in helping. -

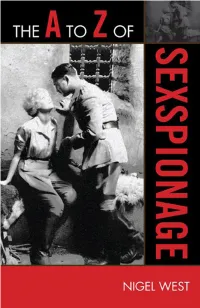

Nigel West, 2009

OTHER A TO Z GUIDES FROM THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. 1. The A to Z of Buddhism by Charles S. Prebish, 2001. 2. The A to Z of Catholicism by William J. Collinge, 2001. 3. The A to Z of Hinduism by Bruce M. Sullivan, 2001. 4. The A to Z of Islam by Ludwig W. Adamec, 2002. 5. The A to Z of Slavery & Abolition by Martin A. Klein, 2002. 6. Terrorism: Assassins to Zealots by Sean Kendall Anderson and Stephen Sloan, 2003. 7. The A to Z of the Korean War by Paul M. Edwards, 2005. 8. The A to Z of the Cold War by Joseph Smith and Simon Davis, 2005. 9. The A to Z of the Vietnam War by Edwin E. Moise, 2005. 10. The A to Z of Science Fiction Literature by Brian Stableford, 2005. 11. The A to Z of the Holocaust by Jack R. Fischel, 2005. 12. The A to Z of Washington, D.C. by Robert Benedetto, Jane Dono- van, and Kathleen DuVall, 2005. 13. The A to Z of Taoism by Julian F. Pas, 2006. 14. The A to Z of the Renaissance by Charles G. Nauert, 2006. 15. The A to Z of Shinto by Stuart D. B. Picken, 2006. 16. The A to Z of Byzantium by John H. Rosser, 2006. 17. The A to Z of the Civil War by Terry L. Jones, 2006. 18. The A to Z of the Friends (Quakers) by Margery Post Abbott, Mary Ellen Chijioke, Pink Dandelion, and John William Oliver Jr., 2006 19. -

Statement by Press Secretary Fitzwater on the President's Meeting with Prime Minister Patrick Manning of Trinidad and Tobago N

Administration of George Bush, 1992 / May 12 ry Council on Unemployment Compensa- through the Disaster Unemployment Assist- tion to study and make recommendations ance Program. on permanent unemployment compensation The President stated, ‘‘I urge the Con- reforms by February 1, 1993. gress to join us in setting aside partisan poli- As previously announced, workers who tics and moving expeditiously to pass this are unemployed as a result of the disturb- extension so that unemployed workers will ances in Los Angeles and who may not know they can count on these benefits as qualify for standard unemployment benefits the economy begins to recover.’’ will be receiving unemployment benefits Statement by Press Secretary Fitzwater on the President’s Meeting With Prime Minister Patrick Manning of Trinidad and Tobago May 12, 1992 The President met this afternoon with coordinated counternarcotics strategy and Prime Minister Patrick Manning of Trinidad thanked him for his quick action in address- and Tobago. The President congratulated ing the drug problem. The Prime Minister him on his plans to further liberalize Trini- expressed his appreciation to the President dad and Tobago’s economy by removing im- for the support of the United States and port restrictions and promoting privatiza- reaffirmed his commitment to economic re- tion. He praised Prime Minister Manning’s forms and a strong counternarcotics effort. Nomination of Marilyn McAfee To Be United States Ambassador to Guatemala May 12, 1992 The President today announced his inten- served as Counselor of Public Affairs at the tion to nominate Marilyn McAfee, of Flor- U.S. Embassy in Santiago, Chile, 1986–89; ida, a career member of the Senior Foreign and in Caracas, Venezuela, 1983–86. -

John Allen Cushing

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JOHN ALLEN CUSHING Interviewed By: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview Date: September 10, 2009 Copyri ht 2009 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in New York; raised in New York and Hawaii. Reed College School for international Training, Brattleboro, )T Wonju, Korea; Peace Corps; ,nglish language instructor 19.701971 ,ducation ,n2ironment Anti0communism Relations with ,mbassy Assassination attempt on Park Chung Hee Korean army 3e4ico5 ,nglish language instructor 197101971 Studies and teaching in 3e4ico and 6apan and New 3e4ico 197101977 Rasht, Iran; ,nglish language instructor, Iran Na2y 197701977 School for International Training 3ujaheddin terrorism Tacoma Washington5 Bilingual education program 197701988 Foreign0born students Law suit Positions and duties ,ntered the Foreign Ser2ice 1988 ,ntrance e4aminations Family Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic5 Consular Officer 198801991 ,n2ironment Public utilities 1 Fraud Case load Haitians Ambassador Paul Taylor State Department5 FSI5 Dutch language training 1991 The Hague, etherlands5 Political Officer 199101992 Surinam and Dutch Antilles Tenure issue State Department5 Andean Affairs Officer 199201994 Tenure issue resol2ed Guatemala City, Guatemala5 ,conomic/Labor Officer 199401997 Ambassador 3arilyn 3cAfee Insurgency refugees United Nations Refugee Organizations 6acob Arbenz Human Rights ,n2ironment President Ramiro de Leon Carpio Peace Accord Port 3oresby, Papua New Guinea5 Consular/Political