Human Rights in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Farewell to Arms, by Ernest Hemingway

A Farewell to Arms BY Ernest Hemingway Book One 1 In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves. The plain was rich with crops; there were many orchards of fruit trees and beyond the plain the mountains were brown and bare. There was fighting in the mountains and at night we could see the flashes from the artillery. In the dark it was like summer lightning, but the nights were cool and there was not the feeling of a storm coming. Sometimes in the dark we heard the troops marching under the window and guns going past pulled by motor-tractors. There was much traffic at night and many mules on the roads with boxes of ammunition on each side of their pack-saddles and gray motor trucks that carried men, and other trucks with loads covered with canvas that moved slower in the traffic. -

Fredrik Reinfeldt

2014 Press release 03 June 2014 Prime Minister's Office REMINDER: German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte to Harpsund On Monday and Tuesday 9-10 June, Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt will host a high-level meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte at Harpsund. The European Union needs to improve job creation and growth now that the EU is gradually recovering from the economic crisis. At the same time, the EU is facing institutional changes with a new European Parliament and a new European Commission taking office in the autumn. Sweden, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands are all reform and growth-oriented countries. As far as Sweden is concerned, it will be important to emphasise structural reforms to boost EU competitiveness, strengthen the Single Market, increase trade relations and promote free movement. These issues will be at the centre of the discussions at Harpsund. Germany, the UK and the Netherlands, like Sweden, are on the World Economic Forum's list of the world's ten most competitive countries. It is natural, therefore, for these countries to come together to compare experiences and discuss EU reform. Programme points: Monday 9 June 18.30 Chancellor Merkel, PM Cameron and PM Rutte arrive at Harpsund; outdoor photo opportunity/door step. Tuesday 10 June 10.30 Joint concluding press conference. Possible further photo opportunities will be announced later. Accreditation is required through the MFA International Press Centre. Applications close on 4 June at 18.00. -

This Is Not a Textual Record. This Is Used As an Administrative Marker by the Chnton Presidential Library Staff

Case Number: 2009-1155-F FOIA MARKER This is not a textual record. This is used as an administrative marker by the CHnton Presidential Library Staff. Folder Title: Chile-Summit I, 1998 [Summit of the Americas] [6] Staff Office-Individual: Inter-American Affairs Original OA/ID Number: 1934 Row: Section: Shelf: Position: Stack: 37 6 7 1 V THE WHITE HOUSE WASH INGTON April 10, 1998 MEMORANDUM TO JOHN PODESTA MACK McLARTY JIM STEINBERG GENE SPERLING FROM: THURGOOD MARSHALL, JR. KRIS BALDERSTON ,,yl^ SUBJECT: CABINET PARTICIPATION IN THE CHILE TRIP UPDATE The following attachment is an updated version of the schedule for the Cabinet's participation in the President's trip to Santiago, Chile. Please contact us if you have any questions. Attachment cc: David Beaubaire Nelson Cunningham Nichole Elkon Laura Graham Sara Latham Laura Marcus Elisa Millsap Janet Murguia Ted Piccone Jaycee Pribulsky Steve Ronnel Cabinet Schedules SUMMIT OF THE AMERICAS-SANTIAGO, CHILE ARIL 1998 Time POTUS Schedule Time Cabinet Schedule WEDNESDAY. APRIL 15TH 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route Santiago 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route [flight time: 10 hours, 15 minutes] Santiago [time change: none] Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey depart RON AIR FORCE ONE RON A IR FORCE ONE THURSDAY APRIL 16TH 7:00 am Arrive Santiago 7:00 Arrive Santiago Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey arrive 7:10 am- Arrival Ceremony 7:10- Arrival Ceremony 7:25 am TARMAC 7:25 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky Santiago Airport McCaffrey attend Open Press 8:00 am Arrive Hyatt Regency Hotel 8:00 am- Down Time 9:30 am Hyatt Regency Hotel 10:25 am- State Arrival Ceremony 10:25- State Arrival Ceremony 10:35 am Courtyard - La Moneda Palace 10:35 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, Press TBD McCaffrey attend 10:35 am- Restricted Bilateral with President Frei 11:25 am President's Office - La Moneda Palace Official Photo Only Note: Potus plus 5. -

REPORT No. 138/18 PETITION 687-11 FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT GABRIELA BLAS BLAS and C.B.B.1 CHILE NOVEMBER 21, 20182

OEA/Ser.L/V/II. REPORT No. 138 /18 Doc. 155 21 November 2018 PETITION 687- 11 Original: Spanish FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT REPORT GABRIELA BLAS BLAS AND HER DAUGHTER C.B.B. CHILE Elctronically approved by the Commission on November 21, 2018. Cite as: IACHR, Report No. 138/ 18, Petition 687-11. Friendly Settlement G.B.B. and C.B.B. November 21, 2018 . www.cidh.org REPORT No. 138/18 PETITION 687-11 FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT GABRIELA BLAS BLAS AND C.B.B.1 CHILE NOVEMBER 21, 20182 I. SUMMARY AND PROCEDURAL CONSIDERATIONS RELATED TO THE FRIENDLY SETTLEMENT PROCEEDINGS BEFORE THE IACHR 1. On May 15, 2011, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Commission” or “the IACHR”) received a petition lodged by the Humanas Corporation Regional Human Rights and Gender Justice Center and the Observatory on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, alleging the international responsibility of the Chilean State (hereinafter “the State” or “the Chilean State”) for the alleged violation of Article 1.1 (obligation to respect rights), Article 2 (domestic legal effects), Article 5 (right to humane treatment), Article 7 (right to personal liberty), Article 8.1 (right to a fair trial), Article 17 (rights of the family), Article 19 (rights of the child), Article 24 (right to equal protection), Article 25 (right to judicial protection), and Article 26 (progressive development) of the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the Convention” or “the American Convention”), and for violating Articles 7 (a) and (b), 8, 9, and 26 of the Convention of Belem do Para, with respect to Gabriela Blas and her daughter C.B.B. -

Enkaz Devralmak 2

ENKAZ DEVRALMAK 2. ÖZET KİTAP Bu özet, III Bölüm ve 27 Alt Bölümden oluşan 1. ENKAZ DEVRALMAK özet kitabının devamıdır. BÖLÜM IV “Şu Palyaçoları Başından At” Nixon ve Ford Yönetimleri Döneminde CIA 1968 – 1976 28. “O Palyaçolar Orada Ne Yapıyor?” Helms 1968 baharında, tepesine dikilecek yeni patronun, ya Robert Kennedy, ya da Richard Nixon olacağından korkuyordu. Kennedy, teşkilâtın gücünü istismar etmiş, Helms’e de gayet soğuk ve aşağılayıcı tavırlar almıştı. Başkan adayı olur, sonra da seçilip Başkomutan kisvesini de kuşanırsa, teşkilâtın kendisi hakkındaki gizli dosyalarının tehdidini ensesinde hissedecekti. R. Kennedy seçim kampanyası sırasında bir suikasta kurban gitti. Helms, bu cinayete çok şaşırmış ama fazla da üzülmemişti doğrusu. Richard Nixon ise başka türlü bir sorundu. CIA’nın bir yığın tatlı su elitistleri, Kennedy’nin adamları ve dedikoducular ile dolu olduğunu düşünürdü. John Kennedy ile girişip kıl payı kaybettiği seçim yarışı sırasında yaşanan o meşhur TV tartışmasında yediği gollerin paslarını da rakibine, CIA’nın verdiğine inanıyordu. Nixon, eğer o seçimleri kazansaydı, gizli operasyonları yürütmek için CIA dışında bir örgüt kuracağını 1962’de kaleme aldığı hatıralarında (Six Crisis – Altı Kriz) yazmıştı. CIA’nın yüreğini sökeceğini belirtiyordu açıkça. Helms ve Nixon ilk kez 1968 Ağustos’unda, Başkan Johnson’un çiftliğindeki bir yemek sırasında uzun uzadıya konuştular. Nixon Helms’e, K. Vietnamlıların ABD’yi yendiklerine ilişkin düşüncelerinin sürüp sürmediğini sordu. Helms, düşmanın Dien Bien Phu zaferinden beri bu düşüncede olduğunu söyledi. Nixon’un duymak istediği son şeydi bu. Nixon, seçimleri kazandıktan sonra Johnson’a Helms hakkındaki düşüncelerini sordu, onu görevinde tutmalı mıydı? “Yetenekli ve sadık bir adamdır” dedi Johnson, “Ben olsam tutardım”. Helms yakında bu sadakatinin faturasının ne olduğunu öğrenecekti. -

Commencement 1961-1970

THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY BALTIMORE, MARYLAND Conferring of Degrees at the close of the eighty-sixth academic year JUNE 12, 1962 Keyser Quadrangle Homewood ORDER OF PROCESSION The Graduates Marshals Carpenter Edgar A. | whs H. J. Johnson Alphonse Chapanis Richard J. Kok.es Carl F. Christ James L. Kuethe Stanley Corrsin Alvin Nason Palmer Futcher Peter E. Wagner John W. Gryder Charles M. Wylie * The Faculties Marshals James W. Poultney and John Walton * The Deans, The Trustees and Honored Guests Marshals Nathan Edelman and M. Gordon Wolman * The Chaplain The Presentors of the Honorary Degree Candidate The Candidates The Commencement Speaker The Chairman of the Board of Trustees The President of the University Chief Marshal Donald H. Andrews Assistant Marshal Francis H. Clauser * For the Presentation of Diplomas Marshals Maurice J. Bessman Stewart H. Hulse, Jr. William H. Huggins W. Kelso Morrill The ushers are undergraduate students of The Johns Hopkins University ORDER OF EVENTS Milton Stover Eisenhower, President of the University, presiding PROCESSIONAL MARCHE SOLENNELLE — FELIX BOROWSKI John H. Elterman, Organist The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing until after the Invocation and the singing of the National Anthem. INVOCATION The Right Reverend Noble C. Powell * THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER THE UNIVERSITY ODE * GREETINGS TO PARENTS CHARLES S. GARLAND Chairman of the Board of Trustees * CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES WILLIAM BENNETT KOUWENHOVEN Presented by Ferdinand Hamburger, Jr. JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON Presented by Francis H. Clauser * ADDRESS JULIUS ADAMS STRATTON President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology ORDER OF EVENTS Continued CONFERRING OF DEGREES ON CANDIDATES Presented by Dean G. -

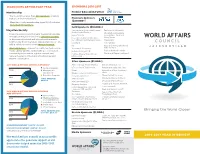

2016-2017 Year in Review

HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS PAST YEAR SPONSORS 2016-2017 Membership Premier Education Partner • The Council has more than 900 members, of whom half are at the Premier level. Platinum Sponsors ($20,000+) • Magellan Society membership (ages 21-40) includes more than 50 members. Gold Sponsors ($10,000+) Magellan Society Association of Corporate Counsel Jacksonville University North Florida Chapter The Mackowski Family Council Leaders connected with Young Professionals • Brunet-García Foundation - Dick and throughout the year via monthly Luncheon Ladders Coastal Construction Products, Marty Jones to discuss professional and international interests. Inc. - William and Barbara Harrell Mayo Clinic Additionally, Board members were paired one-on-one EverBank Pet Paradise with a selected cohort for the Mentor Program. FIS Gary and Nancy Chartrand • Quarterly Saloon collaborations with the Jacksonville The Haskell Company Advised Fund Public Library and the Jacksonville Zoo connected Holland & Knight LLP Paul and Nina Goodwin community issues within a global context and Holmes Private Client Group - David and Elaine Strickland featured experts in the fields of technology and Marty Jones wildlife conservation. Silver Sponsors ($5,000+) 2016 WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL EXPENSES* Adecco Group North America Bob and Sandy Cook Speaker Program CFA Society of Jacksonville Robert and Sallie Ann Hart 70% Management Chase Admiral and Mrs. Jonathan T. and General Chubb Personal Risk Services Howe Education Program Foley & Lardner LLP Diane DeMell Jacobsen 16% TOTAL EXPENSES: JAX Chamber Randy and Becky Johnson $815,417 McGuireWoods LLP Chuck and Nicki Moorer 14% Regency Centers Russell and Joannie Newton Retina Associates, P.A. -Fred Peter Rummell Lambrou, M.D. and Pat Fred and Susan Schantz 2016 WORLD AFFAIRS COUNCIL REVENUE Andrews Jay and Deannie Stein AND SUPPORT* US Assure Foundation Trust Sponsorships U.S. -

The Foreign Service Journal, May 1979

tfTNING A/j- BRE . DAMAGE LIABILITY . TRANSIT/WAR INJURY BODILY RISKS . PROPERTY DAMAGE If, for any reason, you plan to live abroad for awhile—think travel-pak. Travel-pak will cover the household and FIRE personal possessions you take with you—on the . way—while there (including storage if desired) and back again. DAMAGE Travel-pak also includes personal liability coverage providing financial protection against those occurrences for which you might become liable. LUGGAGE When you plan to live abroad for awhile— think travel-pak. LIABILITY Return the coupon below for complete details —or call if you’re in a hurry! And when you return to the Washington area —call us—we’ll be happy to help you set up a STOLEN sound, economical insurance program covering your home, auto and life. ■ s SEND FOR DETAILS-TODAY 21A | Tell me about TRAVEL-PAK. WHEN YOU'RE GOING TO LIVE ABROAD! James W. Barrett Company, Inc. Name REED SHAW STENHOUSE INC. OF WASHINGTON, D.C. Insurance Brokers Address w 1140 Connecticut Ave., N.W. Washington. D.C. 20036 Telephone: 202-296-6440 City State Zip A REED SHAW STENHOUSE COMPANY FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL American Foreign Service Association MAY 1979: Volume 56, No. 5 Officers and Members of the Governing Board ISSN 0015-7279 LARS HYDLE, President KENNETH N. ROGERS, Vice President THOMAS O'CONNOR, Second Vice President FRANK CUMMINS, Secretary M. JAMES WILKINSON. Treasurer RONALD L. NICHOLSON, AID Representative PETER WOLCOTT, ICA Representative Communication re: JOSEPH N. MCBRIDE, BARBARA K. BODINE, Immigration Policy ROBERT H. STERN, State Representatives EUGENE M. BRADERMAN & ROBERT G. -

Message to the Senate Transmitting 1987 Partial Revision of the Radio Regulations May 12, 1992

May 12 / Administration of George Bush, 1992 Message to the Senate Transmitting 1987 Partial Revision of the Radio Regulations May 12, 1992 To the Senate of the United States: States submitted two reservations and re- With a view to receiving the advice and sponded to a statement submitted by Cuba consent of the Senate to ratification, I trans- directed at U.S. use of radio frequencies mit herewith the Partial Revision of the in Guantanamo. The specific reservations Radio Regulations (Geneva, 1979) signed on and statement are addressed in the report behalf of the United States at Geneva on of the Department of State. October 17, 1987, and the United States Most of the Partial Revision of the Radio reservations and statement as contained in Regulations entered into force October 3, the Final Protocol. I transmit also, for the 1989, for governments that, by that date, information of the Senate, the report of the had notified the Secretary General of the Department of State with respect to the International Telecommunication Union of 1987 Partial Revision. their approval thereof; provisions specifically The 1987 Revision constitutes a partial re- related to the maritime mobile service in vision of the Radio Regulations (Geneva the high frequency bands entered into force 1979), to which the United States is a party. on July 1, 1991. The primary purpose of the present revision I believe that the United States should, is to update the existing regulations pertain- subject to the reservations mentioned ing to the mobile radio services to take into above, become a party to the 1987 Partial account technical advances and the rapid Revision, which has the potential to improve growth of these services, and to implement mobile radio-communications worldwide. -

Blues Notes March 2013

Volume eighteen, number three • march 2013 Raise the RoofTUESDAY, fund APRIL R30TaiseH • 6pm RShowtime featu • THR E 21ingST Saloon tommy CastRo $10 admission for current members of BSO, $20 admission for nonmembers (nonmembers can join BSO at door to receive discounted member admission) Since 1980, the Blues Foundation has been inducting individuals, recordings and literature into the Blues Hall of Fame, but until now there has not been a physical Blues Hall of Fame. Establishing a Blues Hall of Fame enhances one of the founding programs of The Blues Foundation. The “Raise the Roof” campaign calls for up to $3.5 million to create a Blues Hall of Fame in Memphis. It will be the place to: honor inductees year-round; listen to and learn about the music; and enjoy historic mementos of this all-American art form. The new Blues Music Hall of Fame will be the place for serious Blues fans, casual visitors, and wide-eyed students. It will facilitate audience development and membership growth. It will expose, enlighten, educate, and entertain. The BSO Presents ––—— POPA CHUBBY ——–– Sunday, March 17th Whiskey Tango • 311 South 15th Street • Omaha, NE tickets $10 adv and $15 DOS — AlSO — Popa CHUBBY • Wednesday, March 20th • The Zoo Bar-6pm 3RD ANNUAL NEBRASKA BLUES CHALLENGE THURSDAY BLUES SERIES March 24, April 7, April 21 (all Sundays) 4727 S 96th Plaza Mark your Calendar All Shows 5:30pm Watch OmahaBlues.com and see the February 28th .............................. The Brandon Santini Band ($8) poster in this issue for schedules! March 7th .......................................................... -

Interview with Stephen F. Dachi

Library of Congress Interview with Stephen F. Dachi The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History ProjectInformation Series STEPHEN F. DACHI Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: May 30, 1997 Copyright 2001 ADST Q: Today is May 30, 1997. This is an interview with Stephen F. Dachi. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. To begin at the beginning, could you tell me when and where you werborn and something about your family? DACHI: I was born in 1933 in Hungary. My father was a dentist. My mother was a physician. They both died when I was three years old in 1936, before the war. My grandparents “inherited me.” They happened to live in Romania. So, I went there just before the Germans marched into Austria, which is my first memory of arriving in Timisoara to live with my grandparents. Then I spent World War II there with them trying to survive. After the war, in 1948, an uncle and aunt who had gone to Canada before the war brought me out there. Q: During the war, what went on then in Romania, particularly as a Hungarian? There was a massive change of borders and everything else at that time. Did you get caught in that? Interview with Stephen F. Dachi http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000263 Library of Congress DACHI: Very definitely, both that and the Holocaust. It has always been hell for Hungarians living in Romania. Kids would curse and harass us if they overheard us speaking Hungarian in the street. -

Manuel-Riesco-Is-Pinochet-Dead.Pdf

manuel riesco IS PINOCHET DEAD? es, quite dead. To make sure, the grandson of General Prats, Pinochet’s predecessor, spat on the former dictator’s corpse as it lay in state in December 2006, revoltingly bloated as the result of an addiction to chocolate and other Ygoodies. Prats certainly inherited the attitude of his grandfather, who was blown up in his car in Buenos Aires on Pinochet’s orders, together with his wife—a cowardly crime typical of the dictator’s treacherous nature. The Prats family well remember how the Pinochets would visit them frequently while grandfather Carlos was still commander-in-chief, always showing a meek and servile disposition. Still, the younger Prats needed courage for this final gesture, as Pinochet continues to attract the fervour of a rich and hate-filled—if ageing—Santiago mob. Led by the rightist parties, they gave vociferous expression to this on the occasion of the funeral. As usual, this was under the protection of the army, shame- fully authorized by the Bachelet government to render final honours to its former Commander-in-Chief. In a gesture of minimum dignity, the President herself refused to honour him as a head of state. She had suffered prison and torture under Pinochet, together with her mother, after her father, General Bachelet, had already been brutally murdered— paying in this way for his loyalty to President Allende. The military pomp was all the more grotesque given that Pinochet had spent his final days under house arrest for his crimes against humanity, and was facing trial for an embezzlement of public funds without prec- edent in Chilean history.