Reillymasselot Published 2017.Pdf (554.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CFR 8203 Crown Forest Fins.FA 25/8/03 11:45 AM Page 12

REPORT TO APPOINTORS INSIDE: PRUDENT TRUSTEESHIP MAORI AFFAIRS SELECT COMMITTEE CENTRAL NORTH ISLAND POLICY CROWN FORESTRY RENTAL TRUST CFR 8203 A/R front.FA 25/8/03 12:19 PM Page 1 CFR 8203 A/R front.FA 25/8/03 12:19 PM Page 2 FRONT COVER IMAGE - TOP RIGHT BOARD OF TRUSTEES Oyster sellers at the Gate Pa, Horatio Robley Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (B.017082) Sir Graham Latimer Prof Whatarangi Winiata Mr Lou Tangaere Ms Maryan Street Mr Paul Carpinter Mr Gregory Fortuin Mr Paul Morgan Ms Angela Foulkes Mr Hemi-Rua Rapata VISION To enhance capacity within Maori communities to achieve their desired outcomes from Treaty claims. STATEMENT OF STRATEGIC POSITION CFRT supports early settlement of claims involving Crown forest licensed land for the benefit of all New Zealanders. We will build on our recognised strengths and optimise the benefit to Maori of the assistance we provide. Our priority will be to support early settlement in the Central North Island and then other early settlements where viable opportunities arise. FOCUS OF WORK We will build and consolidate business relationships with Maori and others by: • effectively communicating our core purpose and processes through our communication strategy; • formally engaging with those who add value to our core purpose; and • capitalising on experience to advance our core purpose by evaluating our performance. We will influence settlement policies by: • delivering high-quality information to support early settlement; and • promoting innovative products and programmes to facilitate early settlement. We will achieve internal efficiencies by: • supporting staff to achieve our core purpose; and • aligning our organisation to achieve its core purpose. -

Fiftieth Parliament of New Zealand

FIFTIETH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 7 August 2013 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Freepost Parliament, Adams, Hon Amy Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 6831 Minister for the Environment Wellington 6160 (04) 817 6531 Minister for Communications Selwyn National [email protected] and Information Technology Associate Minister for Canter- 829 Main South Road, Templeton (03) 344 0418/419 bury Earthquake Recovery Christchurch Fax: (03) 344 0420 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Ardern, Jacinda List Labour Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9388 Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 472 7036 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 817 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6445 Ardern, Shane Taranaki–King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Auchinvole, Chris List National (04) 817 6936 Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9392 Bakshi, Kanwaljit Singh National List Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 473 0469 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Banks, Hon John Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Leader, ACT party Wellington 6160 Minister for Regulatory Reform [email protected] (04) 817 9999 Minister for Small Business ACT Epsom Fax -

SPARKING CREATIVITY in NEW YORK NANO GIRL Making Science Fun

ALUMNI PROFILE THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND ALUMNI MAGAZINE | Spring 2014 SPARKING CREATIVITY IN NEW YORK NANO GIRL Making science fun CHARTER SCHOOLS Are they working? Ingenio / Spring 2014 / 1 ALUMNI PROFILE 1/3 DEPOSIT 1/3 12 MONTHS 1/3 24 MONTHS^ WHAT’S STOPPING YOU? 2.9% INTEREST + 3 YEARS FREE SERVICING.* If you’ve been waiting for the perfect time to buy a brand new Volvo, the wait is over. With payments spread over two years at just 2.9% p.a. and three years free servicing, there’s nothing stopping you. BOOK YOUR TEST DRIVE TODAY. 0800 4 VOLVO OR VISIT VOLVOCARS.CO.NZ *Non-transferable Service Plan covers all factory scheduled maintenance for the fi rst 3 years or 60,000km, whichever occurs fi rst. ^Offer based on recommended retail purchase price plus on road costs fees and charges including a documentation fee of $375. This offer is not available in conjunction with any other offers and is valid until 31st December 2014 or while stock lasts. Offer valid for new cars only. 43682 payable by 1/3 deposit, 1/3 in 12 months and the fi nal 1/3 in 24 months with interest calculated at 2.9% p.a. Finance provided by Heartland Bank Limited and subject to normal leading criteria, conditions, For further details please contact your nearest Volvo Dealer. This promotional offer is not available on XC60 D5 AWD Limited Edition. XC70 D5 Kinetic is only eligible for the Service Plan offer at $69,900. # 43682 Volvo Q4 Print Campaign-Ingenio DPS.indd 1 22/10/14 3:12 PM ALUMNI PROFILE 1/3 DEPOSIT 1/3 12 MONTHS 1/3 24 MONTHS^ WHAT’S STOPPING YOU? 2.9% INTEREST + 3 YEARS FREE SERVICING.* If you’ve been waiting for the perfect time to buy a brand new Volvo, the wait is over. -

House of Representatives List of Members

FORTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 1 September 2008 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Anderton, Hon Jim Freepost Parliament, (04) 470 6550 Leader, Progressive Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 495 8441 Minister of Agriculture Wellington 6160 Minister for Biosecurity Minister of Fisheries Wigram Progressive [email protected] Minister of Forestry Minister responsible for the 296 Selwyn St, Spreydon, Christchurch (03) 365 5459 Public Trust PO Box 33 164, Barrington, Christchurch Fax (03) 365 6173 Associate Minister of Health [email protected] Associate Minister for Tertiary Education Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6447 Ardern MP, Shane Taranaki – King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 470 6936 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 439 6445 Auchinvole, Chris List National Wellington 6160 [email protected] (04) 470 6572 Barker, Hon Rick Freepost Parliament Fax (04) 472 8036 Minister of Internal Affairs Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Minister of Civil Defence Wellington 6160 Minister for Courts List Labour [email protected] Minister of Veterans’ Affairs Associate Minister of Justice PO Box 1245, Hastings (06) 876 8966 Fax (06) 876 4908 Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9906 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) -

The Mixed Member Proportional Representation System and Minority Representation

The Mixed Member Proportional Representation System and Minority Representation: A Case Study of Women and Māori in New Zealand (1996-2011) by Tracy-Ann Johnson-Myers MSc. Government (University of the West Indies) 2008 B.A. History and Political Science (University of the West Indies) 2006 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies In the Graduate Academic Unit of the School of Graduate Studies Supervisor: Joanna Everitt, PhD, Dept. of History and Politics Examining Board: Emery Hyslop-Margison, PhD, Faculty of Education, Chair Paul Howe, PhD, Dept. of Political Science Lee Chalmers, PhD, Dept. of Sociology External Examiner: Karen Bird, PhD, Dept. of Political Science McMaster University This dissertation is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK April, 2013 © Tracy-Ann Johnson-Myers, 2013 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the relationship between women and Māori descriptive and substantive representation in New Zealand’s House of Representatives as a result of the Mixed Member Proportional electoral system. The Mixed Member Proportional electoral system was adopted in New Zealand in 1996 to change the homogenous nature of the New Zealand legislative assembly. As a proportional representation system, MMP ensures that voters’ preferences are proportionally reflected in the party composition of Parliament. Since 1996, women and Māori (and other minority and underrepresented groups) have been experiencing significant increases in their numbers in parliament. Despite these increases, there remains the question of whether or not representatives who ‘stand for’ these two groups due to shared characteristics will subsequently ‘act for’ them through their political behaviour and attitudes. -

Joint Parliamentary Statement for a Middle East Free from Nuclear Weapons and All Other Weapons of Mass Destruction Endorsers As at May 5

Joint Parliamentary Statement for a Middle East Free from Nuclear Weapons and all other Weapons of Mass Destruction Endorsers as at May 5 Argentina Czech Republic (continued) Senator Sonia Escudero, Vice President of the Ivana Levá MP Parliamentary Assembly Europe Hana Orgoníková MP Ladislav Velebný MP Australia Renáta Witoszová MP Amanda Bresnan MP Caroline Le Couteur MP (ACT) Denmark Jill Hall MP Frank Aaen, MP (EL) Colleen Hartland MP (VIC) Eigil Andersen, MP (SF) Stephanie Key MP (SA) Liv Holm Andersen, MP (RV) Senator Scott Ludlam Jørgen Arbo-Bæhr, MP (EL) Melissa Parke MP Anne Baastrup, MP (SF) Andrew Wilkie MP Pernille Vigsø Bagge, MP (SF) Alison Xamon MP (WA) Jacob Bjerregaard, MP (S) Stine Brix, MP (EL) Austria Özlem Sara Cekic, MP (SF) Christine Muttonen MP Per Clausen, MP (EL) Alexander Van der Bellen MP Jonas Dahl, MP (SF) Karina Lorentzen Dehnhardt, MP (SF) Kingdom of Bahrain Lars Dohn, MP (EL) Benny Engelbrecht, MP (S) Dr Salah Ali Moh’d Abdulrahman Steen Gade, MP (SF) Henning Hyllested, MP (EL) Bangladesh Thomas Jensen, MP (S) Saber Chowdhury MP, President of the Inter Jens Joel, MP (S) Parliamentary Union Standing Committee on Peace Christian Juhl, MP (EL) and Security Rosa Lund, MP (EL) Holger K. Nielsen, MP (SF) Belgium Sara Olsvig, MP (IA) Eva Brems MP Jesper Petersen, MP (SF) Senator Piet De Bruyn Lisbeth Bech Poulsen, MP (SF) Dirk Van der Maelen MP, Deputy-Chair of the Johanne Schmidt-Nielsen, MP (EL) Foreign Affairs Committee Pernille Skipper, MP (EL) Zenia Stampe, MP (RV) Canada Finn Sørensen, MP (EL) Peter Julian, -

Newsletter Final 57.Pub

Newsletter 57 Term 4, 2009 Fighting for ACE in Schools Inside this issue: Charlie Herbert 2 Award Winner The Last Hurrah? 2 President’s Report 3 ACE Cuts! - 4 Impact on Communities Executive - 10 Contact Details CLASS 11 Life Members LEFT: The march down Queen Street against the cuts passes Auckland’s Town Hall, on CLASS 12 Saturday 12 September, the national day of action. Conference RIGHT: Maryke hands over the Petition to Maryan Street and Phil Goff. Report Budget Cuts Decimate ACE public attention, interest, desire and calls he May budget announce- to action and importantly – we got the ment to cut 80% funding for attention of influencers and decision mak- schools based ACE shocked ers. Tschools and communities nationwide. CLASS adopted a multi-faceted approach Editor: Liz Godfrey Our revolt against the government deci- to the crisis that began with a very public PO Box 34-603 sion was handled with all the class and campaign whilst negotiating with Minister BIRKENHEAD dignity befitting of our one hundred Tolley and TEC to reinstate funding. Auckland 0746 year kiwi tradition and history. In a CLASS also provided pastoral care to time of crisis, CLASS mobilised and members and shared information on alter- P: 09-481-0144 although the outcome was not what we native funding models for schools. F: 09-481-0143 wanted, the achievement was nonethe- Your contribution to the campaign was E: [email protected] less significant. Our “Stop Night Class massive. Over 200 stories featured in local Cuts” campaign put ACE in the spot- and nationwide newspapers. -

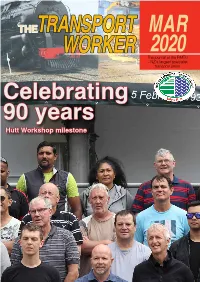

Hutt Workshop Milestone 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL

THETRANSPORT MAR WORKER The2020 journal of the RMTU – NZ's largest specialist transport union Celebrating 90 years Hutt Workshop milestone 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 1 • MARCH 2020 6 FRENCH DISCONTENT Wayne Butson We analyse the causes behind the protests General and strikes coursing through French secretary society.. 11 MONEY MAN RETIRES RMTU Ports Retirement Scheme chair takes retirement himself after setting the Fund on a steady course. Starting the year on a 18 MUST SEE DOCO positive note Helen Kelly Together ELCOME to the first issue ofThe Transport Worker for 2020 and I am is doing the circuit sure you will agree that this is another great issue which chronicles currently and some of the things our leaders, delegates and rank and file members provides a wonderful get up to as part of their daily working life. I use the word 'working' illustration of a in the context that all of us in the RMTU are working for YOU, whether it is me, Wthe paid staff or delegates and activists our efforts are always focussed on what is dedicated and generous union identified and agreed democratically as being best for members. enthusiast doing her Our port members have seen considerable change in recent times and some very best to the bitter have been for the good. One such welcome change had been major staffing changes end. in management in Lyttelton. We were hopeful that this would herald a sea change in behaviour and our relationship with the company and, as they say, the proof is in the pudding. We have seen personal grievances settled to the satisfaction of all COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Some of the 200 parties and we have seen the Lyttelton logistics officers collective agreement settled plus people who gathered last month to in the record time of half a day with a fair deal now subject to member ratification celebrate 90 years of operation at Hutt (as I write this column). -

For Personal Stories See

12 MPs in the main parties have been promised a conscience vote on ACT leader David Seymour’s End of Life Choice Bill if it is debated – as we earnestly hope – in the new Parliament after the September 23 election. The private member’s Bill was drawn from the Parliamentary ballot on June 8 but did not get an airing before the House rose. A snap opinion poll in the New Zealand Herald found 72% of voters surveyed were in favour with only 21% against and 7% undecided, but an impromptu survey found sitting MPs very divided. The Herald found 24 ready to vote for it to go to a select committee and another nine leader Jacinda Ardern and her deputy Kelvin Davis are in probably in favour. Eighteen said they would favour. Green Party policy supports voluntary euthanasia and vote No and another 10 were probably NZ First wants a referendum. negative. The outcome would depend on 58 MPs who were undecided or would not say. Cartoonist Garrick Tremain’s take on the issue is several The National Party’s Bill English, an years old, but remains relevant. We thank him for avowed Catholic, is opposed and Labour’s new permission to reproduce it. WE HAVE A NEW NAME - END-OF-LIFE CHOICE SOCIETY INCORPORATED After 38 years, we have dropped the word “euthanasia” from our name, in accordance with the wishes of an overwhelming majority of members who voted in a postal ballot. We are now known as the End-of-Life Choice Society of New Zealand Incorporated. -

Presentation for Long Service 2 Contents Editorial ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2015

DECEMBER 2015 THE Transport Worker The journal of the RMTU – NZ's largest specialist transport union Presentation for long service 2 CONTENTS EDITORIAL ISSUE 4 • DECEMBER 2015 5 CONGATULATIONS Wayne Butson Andre Evans one of a number of General secretary members recognised in this issue. RMTU 12 KOREAN CONFERENCE Prepareelcome to the finalfor issue of the2016! Union's magazine for 2015. We are fast approaching the conclusion of what has been a very full on year for many elements of our Union membership. As a result it has been RMTU leaders at the ICLS forum. a challenging time for our paid staff and our priceless elected rank and file national office holders, industrial council reps, branch officers and delegates. WIn 2008 I said in this magazine that there is a famous saying, going back over 3000 16 SOLID SUPPORT years: "Every time history repeats itself, the price goes up." I think we have seen some of that within the rail industry with the election of National-led Governments. You all will be able to think of at least one such event and there are more to come sadly, until an alternative is found to John Key in the minds of more voters. In this issue I have asked all our paid staff to supply a reflection piece on this year and I know you will find them an interesting read. I truly enjoy working with such a team of committed unionists and the passion that they bring to the table on your behalf day in and day out. We are very blessed to have such great experienced Thr RMTU has a reputation for supporting and skilled staff in their fields. -

Single Member District Mps Lower House (First Past the Post, Two Round System and Constituency Mps in MMP Systems)

Single Member District MPs Lower House (First Past the Post, Two Round System and constituency MPs in MMP systems) st DISTRICT MPs Out/Not out when first elected Party District First Majority 1 Elected elected Australia Trent Zimmerman Out Liberal North Sydney 2015 Canada Svend Robinson Not Out (1988) NDP Burnaby (Burnaby-Douglas) 1979 3% Réal Ménard Not Out (1994) BQ Hochelaga 1993 36% Libby Davies Not Out (2001) NDP Vancouver East 1997 5% Scott Brison Not Out (2002) Liberal Kings-Hants 1997 6% Bill Siksay Out NDP Burnaby-Douglas 2004 2% Mario Silva Not Out (2004) Liberal Davenport 2004 17% Raymond Gravel Out BQ Repentigny 2006 44% Rob Oliphant Out Liberal Don Valley West 2008 5% Randall Garrison Out NDP Esquimalt-Juan de Fuca 2011 0.5% Danny Morin Out NDP Chicoutimi-Le Fjord 2011 9% Philip Toone Out NDP Gaspesie-Iles-de-la-Madeleine 2011 3% Craig Scott Out NDP Toronto-Danforth 2012 31% Sheri Benson Out NDP Saskatoon West 2015 7% Seamus O’Regan Out Liberal St. John's South-Mount Pearl 2015 21% Randy Boissonnault Out Liberal Edmonton Center 2015 2% France André Labarrère Not Out (1998) Socialist Pyrénées-Atlantiques 1967 ** Franck Riester Not Out (2011) UMP Seine-et-Marne 2007 18% Germany Stefan Kaufmann Out CDU Stuttgart I 2009 5% New Georgina Beyer Out Labour Wairarapa 1999 9% Zealand Tim Barnett Out Labour Christchurch Central 1996 2% Chris Carter Out Labour Te Atatu 1993 10% Grant Robertson Out Labour Wellington Central 2008 5% Louisa Wall Out Labour Manurewa 2011 31% Meka Whaitiri Out Labour Ikaroa-Rāwhiti 2013 15% USA Gerry Studds -

Women Talking Politics

Women Talking Politics A research magazine of the NZPSA New Zealand Political Studies Association Te Kāhui Tātai Tōrangapū o Aotearoa November 2018 ISSN: 1175-1542 wtp Contents From the editors .............................................................................................................................. 4 New Zealand women political leaders today ................................ 6 Claire Timperley - Jacinda Ardern: A Transformational Leader? ............................................. 6 Jean Drage - New Zealand’s new women MPs discuss their first year in Parliament ............. 12 The 148 Women in New Zealand’s Parliament, 1933 – 2018 ................................................. 21 Articles .............................................................................................................................. 25 Julie MacArthur & Noelle Dumo - Empowering Women’s Work? Analysing the Role of Women in New Zealand’s Energy Sector ............................................................................... 25 Igiebor Oluwakemi - Informal Practices and Women’s Progression to Academic Leadership Positions in Nigeria ................................................................................................................ 31 Gay Marie Francisco - The Philippines’ ‘Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity or Expression Equality’ Bill: Who Represents the LGBTQ? ........................................................ 33 Emily Beausoleil - Gathering at the Gate: Listening Intergenerationally as a Precursor to