Feature Clips

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia High School Association State Football Championships Georgia High School Association State Football Championships

GEORGIA HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATION STATE FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS GEORGIA HIGH SCHOOL ASSOCIATION STATE FOOTBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS taBLE OF contents FEATURES 2011 State SPONSOR INDEX Letter from the Executive Director 3 Verizon 2 Georgia Dome Information 5 CHAMPionsHIPS Wilson 2 The Athletic Image 4 GPB Coverage 23 Friday, December 9 Georgia Meth Project 4 Fall Champions 25 Class AA Championship Sports Med South 4 GACA Hall of Fame 26 4:30 p.m. Buford vs. Calhoun Mizuno 16 Sportsmanship Award 27 Class AAAA Championship GA Army National Guard 16 Past State Champions 29 8:00 p.m. Lovejoy vs. Tucker Gatorade 18 Georgia EMC 18 Sports Authority 20 TEAM INFORMATION Saturday, December 10 Georgia Photographics 20 Class AAAAA Team Information 6-7 Class A Championship Marines 21 Class AAAA Team Information 8-9 1:00 p.m. Savannah Chr. vs. Landmark Chr. Choice Hotel 21 Class AAA Team Information 10-11 Class AAA Championship Musco Lighting 22 Class AA Team Information 12-13 4:30 p.m. Burke Co. vs. Peach Co. Bauerfeind 22 Class A Team Information 14-15 Class AAAAA Championship Score Atlanta 24 PlayOn Sports 26 Class AAAAA Bracket 17 8:00 p.m. Grayson vs. Walton Regions Bank 28 Class AAAA Bracket 17 All games will be televised live in HD on Georgia Public Broad- Jostens 28 Class AAA Bracket 19 casting, streamed live on GPB.org and GHSA.tv and available by Field Turf 30 radio on the Georgia News Network, which are available to GNN’s Class AA Bracket 19 statewide radio network of 115 affiliates. The games will be avail- Team IP 30 Class A Bracket 20 able On Demand at GPB.org/sports and GHSA.tv and rebroadcast Georgia Public Broadcasting 31 next week on GPB Knowledge on Atlanta Comcast channel 246 or statewide on over-the-air service at the .3 digital channel. -

2020 Buffalo Fanatics Draft Prospectus

2020 Buffalo Fanatics Draft Prospectus Director of College Scouting Steve Mathes _ @JudgeMathes Positional Outlook Quarterback Buffalo is not going to look to rock the boat by bringing in a legitimate threat to Josh Allen’s job, they believe in him as the franchise QB. Players Met With or “Linked-To” Likewise, they don’t appear to be looking to challenge Matt Barkley as a James Morgan - Florida International back-up either. He has a great relationship with Allen, isn’t threatening his job, and brings traits Allen doesn’t have like anticipatory throwing they hope will rub off on him. That leaves Davis Webb, the practice squad QB, as the only one at real risk of competition. The Bills met with Morgan, but this was before his stock significantly heated up. If the Bills decide to challenge Webb look for a UDFA QB to be the guy to do it. Running Back The Buffalo Bills have only two viable runners on their roster currently in Devin Singletary and TJ Yeldon. They will look to add a third to this tandem to replace Players Met With or “Linked-To” the departed Frank Gore. Cam Akers - Florida St. Gore was known as the “bruiser”. When he was on the field defenses tended to JK Dobbins - Ohio St. know what was coming. It appears from their list of potential targets the Bills Clyde Edwards-Hellaire - LSU are looking to buck that trend. Darrynton Evans - Appalachian St. Zack Moss - Utah On their list are mostly “All-Purpose Backs” and one guy who is all traits (SPEED) D’Andre Swift - Georgia in Darrynton Evans. -

2019 All-Big Ten Football Team

2019 All-Big Ten Football Team As selected by Big Ten coaches OFFENSE FIRST TEAM SECOND TEAM THIRD TEAM Quarterback Justin Fields, Ohio State Tanner Morgan, Minnesota Shea Patterson, Michigan Running Back J.K. Dobbins, Ohio State Stevie Scott III, Indiana Reggie Corbin, Illinois Running Back Jonathan Taylor, Wisconsin Rodney Smith, Minnesota Master Teague, Ohio State Receiver Rashod Bateman, Minnesota Whop Philyor, Indiana Chris Olave, Ohio State Receiver Tyler Johnson, Minnesota KJ Hamler, Penn State David Bell, Purdue Center Tyler Biadasz, Wisconsin Cesar Ruiz, Michigan Josh Myers, Ohio State Guard Ben Bredeson, Michigan Wyatt Davis, Ohio State Michael Onwenu, Michigan Guard Jonah Jackson, Ohio State Steven Gonzalez, Penn State Blaise Andries, Minnesota Tackle Tristan Wirfs, Iowa Branden Bowen, Ohio State Alex Palczewski, Illinois Tackle Jon Runyan, Michigan Thayer Munford, Ohio State Alaric Jackson, Iowa Tight End Brycen Hopkins, Purdue Pat Freiermuth, Penn State Luke Farrell, Ohio State OFFENSE HONORABLE MENTION ILLINOIS: Kendrick Green, Doug Kramer; INDIANA: Peyton Hendershot, Caleb Jones, Simon Stepaniak; IOWA: Tyler Linderbaum, Ihmir Smith-Marsette, Nate Stanley; MARYLAND: Dontay Demus, Javon Leake; MICHIGAN: Zach Charbonnet, Nico Collins, Nick Eubanks, Hassan Haskins, Jalen Mayfield, Sean McKeon; MICHIGAN STATE: Elijah Collins, Cody White; MINNESOTA: Curtis Dunlap Jr., Daniel Faalele, Conner Olson, Sam Schlueter, NEBRASKA: Brenden Jaimes, Dedrick Mills, JD Spielman; NORTHWESTERN: Rashawn Slater; OHIO STATE: K.J. Hill; PENN STATE: -

04 Coaches-WEB.Pdf

59 Experience: 1st season at FSU/ Taggart jumped out to a hot start at Oregon, leading the Ducks to a 77-21 win in his first 9th as head coach/ game in Eugene. The point total tied for the highest in the NCAA in 2017, was Oregon’s 20th as collegiate coach highest since 1916 and included a school-record nine rushing touchdowns. The Hometown: Palmetto, Florida offensive fireworks continued as Oregon scored 42 first-half points in each of the first three games of the season, marking the first time in school history the program scored Alma Mater: Western Kentucky, 1998 at least 42 points in one half in three straight games. The Ducks began the season Family: wife Taneshia; 5-1 and completed the regular season with another offensive explosion, defeating rival sons Willie Jr. and Jackson; Oregon State 69-10 for the team’s seventh 40-point offensive output of the season. daughter Morgan Oregon ranked in the top 30 in the NCAA in 15 different statistical categories, including boasting the 12th-best rushing offense in the country rushing for 251.0 yards per game and the 18th-highest scoring offense averaging 36.0 points per game. On defense, the Florida State hired Florida native Willie Taggart to be its 10th full-time head football Ducks ranked 24th in the country in third-down defense allowing a .333 conversion coach on Dec. 5, 2017. Taggart is considered one of the best offensive minds in the percentage and 27th in fourth-down defense at .417. The defense had one of the best country and has already proven to be a relentless and effective recruiter. -

Minnesota Vs. #4/4 Ohio State 1 2

2021 SCHEDULE MINNESOTA VS. #4/4 OHIO STATE DATE OPPONENT TIME TV RESULT Date/Time: Sept. 2, 2021 / 7 p.m. CT Television: FOX SEPTEMBER Site: Minneapolis Gus Johnson (PXP) 2 #4/4 Ohio State* 7:00 p.m. FOX Stadium: Huntington Bank Joel Klatt (Analyst) 11 Miami (OH) 11:00 a.m. ESPNU Surface: FieldTurf Jenny Taft (Reporter) 18 at Colorado 12:00 p.m. PAC12N Capacity: 50,805 Series Overall: Ohio State Leads 45-7 25 Bowling Green^ 11:00 a.m. TBA Minnesota Ohio State Radio: KFAN 2020: 3-4, 3-4 B1G 2020: 7-1, 5-0 B1G Streak: Ohio State Won 11 OCTOBER Mike Grimm (Play by Play) HC P.J. Fleck HC Ryan Day Series in MN: Ohio State Leads 22-4 2 at Purdue* 11:00 a.m. TBA Darrell Thompson (Analyst) 9th Year (5th at Minnesota) 4th Year (all at Ohio State) Streak: Ohio State Won 13 16 Nebraska* TBA TBA Last Meeting: Ohio State won 30-14 Justin Gaard (Reporter) at Minnesota: 26-19 at Ohio State: 23-2 23 Maryland* TBA TBA in Columbus (10/13/18) Corbu Stathes (Host) vs. Ohio State: 0-1 vs. Minnesota: 0-0 30 at Northwestern* TBA TBA Last U win: 29-17 in Columbus Dan Rowbotham (Engineer) Overall Record: 56-41 at Ohio State: 23-2 NOVEMBER (10/14/00) vs. Ohio State: 0-2 vs. Minnesota: 0-0 6 Illinois* TBA TBA Last U win in MN: 35-31 (11/7/81) 13 at Iowa* TBA TBA 20 at Indiana* TBA TBA FIVE THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 27 Wisconsin* TBA TBA * Big Ten game // ^ Homecoming game // All times Central University of Minnesota football begins its 138th season, 1 and fifth under head coach P.J. -

Mike Clay's 2020 NFL Projection Guide

Mike Clay's 2020 NFL Projection Guide Updated: 9/10/2020 Glossary: Page 2-33: Team Projections Page 34-44: QB, RB, WR and TE projections Page 45-48: Category Leader projections Page 49: Projected standings, playoff teams and 2021 draft order Page 50: Projected Strength of Schedule Page 51: Unit Grades Page 52-61: Positional Unit Ranks Understanding the graphics: *The numbers shown are projections for the 2020 NFL regular season (Weeks 1-17). *Some columns may not seem to be adding up correctly, but this is simply a product of rounding. The totals you see are correct. *Looking for sortable projections by position or category? Check out the projections tab inside the ESPN Fantasy game. *'Team stat rankings' is where each team is projected to finish in the category that is shown. *'Unit Grades' is not related to fantasy football and is an objective ranking of each team at 10 key positions. The overall grades are weighted based on positional importance. The scale is 4.0 (best) to 0.1 (worst). A full rundown of Unit Grades can be found on page 51. *'Strength of Schedule Ranking' is based on 2020 rosters (not 2019 team record). '1' is easiest and '32' hardest. See the full list on page 50. *Note that prior to the official release of the NFL schedule (generally late April/early May), the schedule shown includes the correct opponents, but the order is random *Have a question? Contact Mike Clay on Twitter @MikeClayNFL 2020 Arizona Cardinals Projections QUARTERBACK PASSING RUSHING PPR DEFENSE WEEKLY SCORE PROJECTIONS Player Gm Att Comp Yds TD INT -

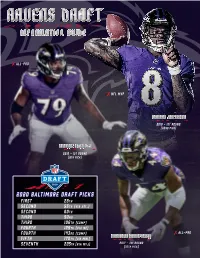

Information Guide

INFORMATION GUIDE 7 ALL-PRO 7 NFL MVP LAMAR JACKSON 2018 - 1ST ROUND (32ND PICK) RONNIE STANLEY 2016 - 1ST ROUND (6TH PICK) 2020 BALTIMORE DRAFT PICKS FIRST 28TH SECOND 55TH (VIA ATL.) SECOND 60TH THIRD 92ND THIRD 106TH (COMP) FOURTH 129TH (VIA NE) FOURTH 143RD (COMP) 7 ALL-PRO MARLON HUMPHREY FIFTH 170TH (VIA MIN.) SEVENTH 225TH (VIA NYJ) 2017 - 1ST ROUND (16TH PICK) 2020 RAVENS DRAFT GUIDE “[The Draft] is the lifeblood of this Ozzie Newsome organization, and we take it very Executive Vice President seriously. We try to make it a science, 25th Season w/ Ravens we really do. But in the end, it’s probably more of an art than a science. There’s a lot of nuance involved. It’s Joe Hortiz a big-picture thing. It’s a lot of bits and Director of Player Personnel pieces of information. It’s gut instinct. 23rd Season w/ Ravens It’s experience, which I think is really, really important.” Eric DeCosta George Kokinis Executive VP & General Manager Director of Player Personnel 25th Season w/ Ravens, 2nd as EVP/GM 24th Season w/ Ravens Pat Moriarty Brandon Berning Bobby Vega “Q” Attenoukon Sarah Mallepalle Sr. VP of Football Operations MW/SW Area Scout East Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Player Personnel Analyst Vincent Newsome David Blackburn Kevin Weidl Patrick McDonough Derrick Yam Sr. Player Personnel Exec. West Area Scout SE/SW Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Quantitative Analyst Nick Matteo Joey Cleary Corey Frazier Chas Stallard Director of Football Admin. Northeast Area Scout Pro Scout Player Personnel Assistant David McDonald Dwaune Jones Patrick Williams Jenn Werner Dir. -

New Orleans Saints Vs Jacksonville Jaguars Sunday, Oct

NEW ORLEANS SAINTS VS JACKSONVILLE JAGUARS SUNDAY, OCT. 13, 2019 ● TIAA BANK FIELD SAINTS POSTGAME NOTES With the win, the Saints move to 5-1 for the second consecutive season, keeping New Orleans in first place in the NFC South. This is the first time New Orleans has started 5-1 in consecutive seasons. The win gives New Orleans a 5-2 record against Jacksonville and extends the club’s winning streak against AFC franchises to nine games. The Saints also extended their streak to 18 wins when leading in the fourth quarter. Head Coach Sean Payton now has 131 career wins, putting him in a tie with Marvin Lewis for 29th place all-time in NFL record books for career victories. Payton improved his record against Jacksonville to 4-0; keeping the Jaguars as one of three teams he has an undefeated record against along with Buffalo and Miami. Offensively, New Orleans racked up 326 yards with 240 passing yards and 104 rushing yards on the way to scoring 13 points. QB Teddy Bridgewater started and won his 21st career game as a starter. Bridgewater completed 24-of-36 passes for 240 yards, a touchdown, and 94.7 quarterback rating. Bridgewater led the Saints on three scoring drives resulting in two field goals and one touchdown. In a drive that spanned the final two quarters, Bridgewater led the saints on an 11-play, 75-yard drive that ended with a four-yard touchdown to pass to TE Jared Cook. In the game-winning drive, he completed five-of-six passes for 58 yards. -

2021 Gold Standard Football Checklist NFL HOBBY

2021 Gold Standard Football Checklist Player Set Card # Team Print Run Brandon Aiyuk Auto - Double Standard Dual Player + Parallels 3 49ers 8 Brandon Aiyuk Auto - Golden Gloves + Parallels 5 49ers 125 Brandon Aiyuk Relic - Gold Rush + Parallels 4 49ers 349 Brandon Aiyuk Relic - Golden Pairs Dual Player + Parallels 6 49ers 349 Brandon Aiyuk Relic - Mother Lode + Parallels 7 49ers 349 Charles Haley Auto - Double Standard Dual Player + Parallels 14 49ers 36 Deebo Samuel Auto - Gold Strike + Parallels 3 49ers 125 Deebo Samuel Relic - Golden Pairs Dual Player + Parallels 6 49ers 349 Elijah Mitchell Auto - Rookies + Parallels 176 49ers 279 Frank Gore Auto - AU + Parallels 8 49ers 60 George Kittle Auto - Gold Scripts + Parallels 15 49ers 36 George Kittle Relic - Gold Gear + Parallels 19 49ers 225 Jerry Rice Auto - Double Standard Dual Player + Parallels 3 49ers 8 Jerry Rice Auto - Golden Records Signatures 10 49ers 5 Joe Montana Auto - Gold Jacket Signatures + Parallels 8 49ers 16 Joe Montana Relic - Hall of Gold Threads + Parallels 16 49ers 125 Nick Bosa Auto - Double Standard Dual Player + Parallels 14 49ers 36 Patrick Willis Auto Relic - Good as Gold + Parallels 26 49ers 125 Patrick Willis Relic - Gold Rush + Parallels 32 49ers 349 Roger Craig Auto - AU + Parallels 18 49ers 125 Ronnie Lott Relic - Hall of Gold Threads + Parallels 7 49ers 199 Steve Young Auto - Golden Records Signatures 18 49ers 5 Steve Young Auto Diamond- Super Bowl Diamond Signatures 8 49ers 10 Trey Lance Auto - Golden Debuts + Parallels 5 49ers 16 Trey Lance Auto - Rookie -

Week 3 Training Camp Report

[Date] Volume 16, Issue 3 – 8/24/2021 Our goal at Footballguys is to help you win more at Follow our Footballguys Training Camp crew fantasy football. One way we do that is make sure on Twitter: you’re the most informed person in your league. @FBGNews, @theaudible, @football_guys, Our Staffers sort through the mountain of news and @sigmundbloom, @fbgwood, @bobhenry, deliver these weekly reports so you'll know @MattWaldman, @CecilLammey, everything about every team and every player that @JustinHoweFF, @Hindery, @a_rudnicki, matters. We want to help you crush your fantasy @draftdaddy, @AdamHarstad, draft. And this will do it. @JamesBrimacombe, @RyanHester13, @Andrew_Garda, @Bischoff_Scott, @PhilFBG, We’re your “Guide” in this journey. Buckle up and @xfantasyphoenix, @McNamaraDynasty let’s win this thing. Your Friends at Footballguys “What I saw from A.J. Green at Cardinals practice today looked like the 2015 version,” Riddick tweeted. “He was on fire. Arizona has the potential to have top-five wide receiver group with DHop, AJ, Rondale Moore, and Christian Kirk.” The Cardinals have lots of depth now at QB: Kyler Murray saw his first snaps this preseason, but the wide receiver position with the additions for Green it was evident Kliff Kingsbury sees little value in giving and Moore this offseason. his superstar quarterback an extended preseason look. He played nine snaps against the Chiefs before giving TE: The tight end position remains one of the big way to Colt McCoy and Chris Streveler. Those nine question marks. Maxx Williams sits at the top of the snaps were discouraging, as Murray took two sacks and depth chart, but it is muddied with Darrell Daniels, only completed one pass. -

Top 200 Fantasy Football PPR Rankings ABCDE

Top 200 fantasy football PPR rankings ABCDE Rk. Pos Player Team WAR Rk. Pos Player Team WAR 1 RB Christian McCaffrey CAR 9.8 51 WR D.J. Moore CAR 3.1 2 RB Ezekiel Elliott DAL 7.2 52 RB Chase Edmonds ARI 3.0 3 RB Alvin Kamara NO 7.0 53 WR Chris Godwin TB 3.0 4 RB Dalvin Cook MIN 7.0 54 WR Cooper Kupp LAR 3.0 5 RB Austin Ekeler LAC 6.8 55 QB Justin Herbert LAC 3.0 6 RB Derrick Henry TEN 6.3 56 RB Javonte Williams DEN 3.0 7 WR Davante Adams GB 6.1 57 RB Michael Carter NYJ 2.9 8 TE Travis Kelce KC 5.9 58 WR Mike Evans TB 2.9 9 QB Patrick Mahomes II KC 5.7 59 RB Kareem Hunt CLE 2.9 10 RB Aaron Jones GB 5.6 60 WR Julio Jones TEN 2.8 11 WR Stefon Diggs BUF 5.6 61 QB Ryan Tannehill TEN 2.8 12 TE Darren Waller LV 5.6 62 WR Tyler Lockett SEA 2.8 13 RB Nick Chubb CLE 5.5 63 RB Raheem Mostert SF 2.7 14 RB Jonathan Taylor IND 5.5 64 TE Mark Andrews BAL 2.7 15 WR Tyreek Hill KC 5.4 65 WR Tee Higgins CIN 2.7 16 RB Saquon Barkley NYG 5.4 66 RB Melvin Gordon III DEN 2.7 17 RB Najee Harris PIT 5.4 67 WR Brandon Aiyuk SF 2.6 18 RB Antonio Gibson WAS 5.2 68 RB Damien Harris NE 2.5 19 RB Clyde Edwards Helaire KC 4.8 69 WR Diontae Johnson PIT 2.5 20 RB D'Andre Swift DET 4.8 70 RB James Robinson JAC 2.5 21 WR Calvin Ridley ATL 4.7 71 WR Adam Thielen MIN 2.5 22 WR A.J. -

Valdosta State University Fact Book 2015-2016

Valdosta State University Fact Book 2015-2016 Office of Institutional Research VSU Fact Book 2015-2016 Table of Contents Cover Page.............................................................................................................. Foreword.................................................................................................................. 1 General Information................................................................................................ 2 Brief Chronology of VSU............................................................................................ 3 Concise Mission Statement....................................................................................... 4 Strategic Goals 2013-2019......................................................................................... 5 Board of Regents Membership.................................................................................... 6 Board of Regents Organizational Chart........................................................................ 7 VSU Organizational Chart.......................................................................................... 8 Biography of President............................................................................................... 9 Accreditation............................................................................................................ 10 Degrees Offered........................................................................................................ 11 Undergraduate......................................................................................................