Viral Modernity? Epidemics, Infodemics, and the 'Bioinformational'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COFAC Today Spring 2017

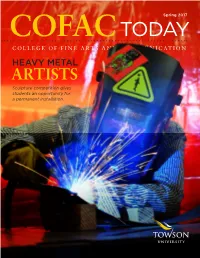

Spring 2017 COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION HEAVY METAL ARTISTS Sculpture competition gives students an opportunity for a permanent installation. COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION DEAN, COLLEGE OF DEAR FRIENDS, FAMILIES, AND COLLEAGUES, FINE ARTS & COMMUNICATION Susan Picinich The close of an academic year brings with it a sense of pride and anticipation. The College of Fine Arts and Communication bustles with excitement as students finish final projects, presentations, exhibitions, EDITOR Sedonia Martin concerts, recitals and performances. Sr. Communications Manager In this issue of COFAC Today we look at the advancing professional career of dance alum Will B. Bell University Marketing and Communications ’11 who is making his way in the world of dance including playing “Duane” in the live broadcast of ASSOCIATE EDITOR Hairspray Live, NBC television’s extravaganza. Marissa Berk-Smith Communications and Outreach Coordinator The Asian Arts & Culture Center (AA&CC) presented Karaoke: Asia’s Global Sensation, an exhibition College of Fine Arts and Communication that explored the world-wide phenomenon of karaoke. Conceived by AA&CC director Joanna Pecore, WRITER students, faculty and staff had the opportunity to belt out a song in the AA&CC gallery while learning Wanda Haskel the history of karaoke. University Marketing and Communications DESIGNER Music major Noah Pierre ’19 and Melanie Brown ’17 share a jazz bond. Both have been playing music Rick Pallansch since childhood and chose TU’s Department of Music Jazz Studies program. Citing outstanding faculty University Marketing and Communications and musical instruction, these students are honing their passion of making music and sharing it with PHOTOGRAPHY the world. -

CABARET SYNOPSIS the Scene Is a Sleazy Nightclub in Berlin As The

CABARET SYNOPSIS The scene is a sleazy nightclub in Berlin as the 1920s are drawing to a close. Cliff Bradshaw, a young American writer, and Ernst Ludwig, a German, strike up a friendship on a train. Ernst gives Cliff an address in Berlin where he will find a room. Cliff takes this advice and Fräulein Schneider, a vivacious 60 year old, lets him have a room very cheaply. Cliff, at the Kit Kat Club, meets an English girl, Sally Bowles, who is working there as a singer and hostess. Next day, as Cliff is giving Ernst an English lesson, Sally arrives with all her luggage and moves in. Ernst comes to ask Cliff to collect something for him from Paris; he will pay well for the service. Cliff knows that this will involve smuggling currency, but agrees to go. Ernst's fee will be useful now that Cliff and Sally are to be married. Fraulein Schneider and her admirer, a Jewish greengrocer named Herr Schultz, also decide to become engaged and a celebration party is held in Herr Schultz shop. In the middle of the festivities Ernst arrives wearing a Nazi armband. Cliff realizes that his Paris errand was on behalf of the Nazi party and refuses Ernst's payment, but Sally accepts it. At Cliff's flat Sally gets ready to go back to work at the Kit Kat Klub. Cliff determines that they will leave for America but that evening he calls at the Klub and finds Sally there. He is furious, and when Ernst approaches him to perform another errand Cliff knocks him down. -

Christopher Isherwood's Camp

Theory and Practice in English Studies Volume 8, No. 2, 2019 E-ISSN: 1805-0859 CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD’S CAMP Thomas Castañeda Abstract In this paper I consider recurrent themes in the work of Christopher Isherwood, a novelist best known for his portrayal of Berlin's seedy cabaret scene just before the outbreak of the Second World War. The themes I discuss each hinge on un- canny discrepancies between youth and old age, male and female, sacred and pro- fane, real and sham. Together, I argue, these themes indicate the author's invest- ment in a queer camp sensibility devoted to theatricality, ironic humor, and the supremacy of style. I focus on specific descriptions of characters, objects, and places throughout the author's work in order to foreground camp's rather exuber- ant interest in artifice, affectation, and excess, as well as its ability to apprehend beauty and worthiness even, or especially, in degraded objects, people, or places. Ultimately, I argue that the term camp, especially as it applies to Isherwood's work, names both a comedic style and a specifically queer empathetic mode rooted in shared histories of hurt, secrecy, and social marginalization. Keywords Artifice; camp; dandy; humor; irony; style; theatricality; queerness * * * CHRISTOPHER Isherwood (1904–1986) first glossed the term camp in a 1954 novel entitled The World in the Evening; there, he describes camp as a way of “ex- pressing what’s basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance” (125). The novel centers around a bisexual widower named Stephen Monk, who flees his second marriage in Los Angeles to live with his “aunt” Sarah – a close family friend – in a small Quaker community outside Philadelphia. -

The Unforgiving Margin in the Fiction of Christopher Isherwood

The Unforgiving Margin in the Fiction of Christopher Isherwood Paul Michael McNeil Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 Copyright 2011 Paul Michael McNeil All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Unforgiving Margin in the Fiction of Christopher Isherwood Paul Michael McNeil Rebellion and repudiation of the mainstream recur as motifs throughout Christopher Isherwood‟s novels and life, dating back to his early experience of the death of his father and continuing through to the end of his own life with his vituperative rant against the heterosexual majority. Threatened by the accepted, by the traditional, by the past, Isherwood and his characters escape to the margin, hoping to find there people who share alternative values and ways of living that might ultimately prove more meaningful and enlightened than those they leave behind in the mainstream. In so doing, they both discover that the margin is a complicated place that is more often menacing than redemptive. Consistently, Isherwood‟s fiction looks at margins and the impulse to flee from the mainstream in search of a marginal alternative. On the one hand, these alternative spaces are thought to be redemptive, thought to liberate and nourish. Isherwood reveals that they do neither. To explore this theme, the dissertation focuses on three novels, The Berlin Stories (The Last of Mr. Norris and Goodbye to Berlin), A Meeting by the River, and A Single Man, because ach of these novels corresponds to marginal journeys of Isherwood— namely, his sexual and creative exile in Berlin from 1929 to 1933, his embrace of Hindu philosophy, and his life as a homosexual. -

El Berlín De Christopher Isherwood

Mito | Revista Cultural, vol. 24, 2015. El Berlín de Christopher Isherwood. Teresa Montiel Alvarez. Cita: Teresa Montiel Alvarez (2015). El Berlín de Christopher Isherwood. Mito | Revista Cultural, 24. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/teresa.montiel.alvarez/25 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: http://www.aacademica.org. El Berlín de Christopher Isherwood Por Teresa Montiel Álvarez el 17 julio, 2015 @lafotera “Yo soy como una cámara con el obturador abierto, pasiva, minuciosa, incapaz de pensar. Capto la imagen del hombre que se afeita en la ventana de enfrente y de la de la mujer en kimono, lavándose la cabeza. Habría que revelarlas algún día, fijarlas cuidadosamente en el papel”. En marzo de 1929 Christopher Isherwood llega a Berlín, y hasta 1933, en que Hitler asciende al poder, fundamentalmente se dedicó a esto: fotografiar en su memoria todo el mosaico de imágenes de la ciudad de entreguerras: lugares, situaciones, personas y personajes, mientras él se introducía en ella y la va desgranando a modo de maestro de ceremonias. Isherwood fue un testigo privilegiado de la transformación de la sociedad berlinesa de la República de Weimar hasta el alzamiento del nazismo. Se acercó a todo tipo de ambientes: desde los más sórdidos cabarets, a relacionarse con judíos pudientes, berlineses venidos a menos, obreros e intelectuales y vividores por igual. Para todos guardó una instantánea en su memoria, que posteriormente pasó por una lente de aumento. -

John Sommerfield and Mass-Observation

131 John Sommerfield and Mass-Observation Nick Hubble Brunel University When the name of John Sommerfield (1908-1991) appears in a work of literary criticism it is usually either in connection with a specific reference to May Day, his experimental proletarian novel of 1936, or as part of a list containing some or all of the following names: Arthur Calder-Marshall, Jack Lindsay, Edgell Rickword, Montagu Slater, Randall Swingler and Amabel Williams-Ellis. As part of this semi-autonomous literary wing of the Communist Party, Sommerfield played his full role in turn on the Left Review collective in the 1930s, in various writers’ groups such as the Ralph Fox Group of the 1930s and the Realist Writers’ Group launched in early 1940, and on the editorial commission of Our Time in the late 1940s, before leaving the Party in 1956. However, significantly for the argument that follows concerning Sommerfield’s capacity to record the intersubjective quality of social existence, he was as much known for his pub going and camaraderie as his politics, with Dylan Thomas once saying “if all the party members were like John Sommerfield, I’d join on the spot” (Croft 66). Doris Lessing came to know him in the early 1950s, after he approached her to join the current incarnation of the Communist Party Writers’ Group, and she describes him fondly in her memoirs: “He was a tall, lean man, pipe- smoking, who would allow to fall from unsmiling lips surreal diagnoses of the world he lived in, while his eyes insisted he was deeply serious. -

Cabaret-Artswfl-Tom

Home Area Artists » Art Fairs & Festivals » Breaking News » Community Theater & Film » Local Art Stops » Public Art » Uncategorized subscribe: Posts | Comments search the site Dr. Kyra Belan share this Breaking SWFL Art News November 1-7, 2014 Cabaret 0 comments Posted | 0 comments Twelve performances of Cabaret come to the Lab Theater on February 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 19, 20, 21, 26, 27 and 28 at 8 p.m., and on February 14 at 2 p.m. There will also be an opening night reception, starting at 7:15 p.m. Tickets are $12 for students and $22 for adults at the door. The theater also offers Thursday night discounts to seniors and military, at $18.50 per ticket. Tickets are available from the theater’s website, www.LaboratoryTheaterFlorida.com or by calling 239.218.0481. In this section, you will find articles about the play, playwright, director and upcoming production of the show at the Laboratory Theater of Florida (posted in date order from oldest to latest). * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Ty Landers turns in Depp-like performance as Kit Kat Klub Master of Ceremonies in Lab Theater’s ‘Cabaret’ (02-07-15) On stage now through February 28 at the Laboratory Theater of Florida is Cabaret, the company’s first-ever musical. Produced and directed by Brenda Kensler, the 1998 Sam Mendes and Rob Marshall revival of the 1966 Broadway production stars Ty Landers as the oversexed, androgynous emcee of the Kit Kat Klub, a role that was reprised by both Joel Gray and Alan Cummings. Gray was the ringmaster in a circus of sexual deviants. -

SPEAKER BIOS March 5, 2020

17th Annual Budget and Tax Briefing March 5-6, 2020 FHI 360, 1825 Connecticut Ave NW, 8th Floor, Washington, DC 20009 SPEAKER BIOS March 5, 2020 WELCOME AND OPENING LUNCHEON Kit Judge, Associate Director, Policy Reform and Advocacy, The Annie E. Casey Foundation and EOF Steering Committee Member, [email protected] Kit Judge joined the Casey Family in 2014 and is Associate Director with the Policy Reform & Advocacy (PRA) team in the External Affairs unit, managing much of the ambitious National Policy Reform and Advocacy portfolio. Prior to joining the Foundation, Kit served as a senior policy and communications advisor for Speaker and Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi in the U.S. House of Representatives for the past ten years. As part of the Democratic Leader's senior staff, Kit developed legislative, political and messaging strategies for the implementation of the Democratic leadership's agenda in the House. Covering a broad range of policy and legislative issues, she served as one of the primary people who conceived, developed, and wrote press and message materials for Speaker Pelosi and other House Democrats. Prior to joining Speaker Pelosi's staff, Kit was a policy advisor and research director for former top House Democrat Richard A. Gephardt. And she began her quarter-century Capitol Hill career with the Democratic Study Group, the preeminent source of legislative information for House Democrats. Kit has a J.D. from George Washington University. After growing up in Richmond, Indiana, she earned a B.A. in political science and psychology from Earlham College. She lives in Silver Spring, Maryland with her husband Bruce Hawkins and teenage son Jackson. -

Political Pseudonyms

BRITISH POLITICAL PSEUDONYMS Suggested additions and corrections always welcome 20th CENTURY Adler, Ruth Ray Waterman Ajax Montagu Slater [in Left Review, which he helped create & edited in 1934] Ajax Junior Guy A Aldred (in the Agnostic Journal). Allen, C Chimen Abramsky [CP National Jewish Committee] Allen, Peter Salme Dutt [née Murrik aka Pekkala; married to Rajani Palme Dutt] Anderson, Irene Constance Haverson [George Lansbury's granddaughter, Comintern courier] Andrews, R F Andrew Rothstein [CPGB] Arkwright, John Randall Swingler [CP writer] Ashton, Teddy Charles Allen Clarke. 1863-1935. [Lancashire dialect novelist and socialist] Atticus William MacCall [pioneer anarchist, reviewer for The National Reformer] Aurelius, Marcus Walter Padley [author of Am I My Brother’s Keeper? Gollancz 1945; Labour MP and President of USDAW] Avis Alfred Sherman (before he became a close advisor to Margaret Thatcher, he had been in theCP in the 1940s, and used this name to write on Jewish issues) Barclay, P J John Archer (Trotskyist civil servant) Baron, Alexander Alec Bernstein [novelist] Barrett, George George Ballard [anarchist] Barrister, A Mavis Hill [Justice in England, LBC, 1938] Thurso, Berwick Morris Blythman [Scottish radical poet, singer-songwriter] B V James Thomson [Radical poet and reviewer] Bell, Lily Mrs Bream Pearce [in Keir Hardie’sLabour Leader] Bennet or Bennett Goldfarb [ECCI rep. to GB & Ireland; Head of Anglo-American Secretariat, C.I.; married Rose Cohen, CPGB. Both shot in 1937] Aka Lipec, Petrovsky, Breguer, Humboldt Berwick, -

Political Pseudonyms

BRITISH POLITICAL PSEUDONYMS Suggested additions and corrections always welcome 20th CENTURY Adler, Ruth Ray Waterman Ajax Montagu Slater [in Left Review, which he helped create & edited in 1934] Ajax Junior Guy Aldred [Scottish anti-parliamentarian communist] Allen, Peter Salme Dutt [née Murrik aka Pekkala; married to Rajani Palme Dutt] Anderson, Irene Constance Haverson [George Lansbury's granddaughter, Comintern courier] Andrews, R F Andrew Rothstein [CPGB] Arkwright, John Randall Swingler [CP writer] Ashton, Teddy Charles Allen Clarke. 1863-1935. [Lancashire dialect novelist and socialist] Atticus William MacCall [pioneer anarchist, reviewer for The National Reformer] Avis Alfred Sherman [before he became a close advisor to Margaret Thatcher, he had been in the CP in the 1940s, and used this name to write on Jewish issues] Barclay, P J John Archer [Trotskyist civil servant] Baron, Alexander Alec Bernstein [author] Barrister, A Mavis Hill [Justice in England, LBC, 1938] Thurso, Berwick Maurice Blythman [Scottish radical poet] Bennet or Bennett Goldfarb [ECCI rep. to GB & Ireland; Head of Anglo-American Secretariat, C.I.; married Rose Cohen, CPGB. Both shot in 1937] Aka Lipec, Petrovsky, Breguer, Humboldt Best, Michael Michael Shapiro [CP] Bilbo, Jack Hugo Baruch [German anti-fascist; in England from 1936 – temporarily interned, set up the Modern Art Gallery in London in 1941; created controversial large-scale erotic sculptures in his Surrey garden] Bishop, John Ted Willis [as author of Erma Kremer & Sabotage! for Unity Theatre in 1941 -

British Political Pseudonyms

BRITISH POLITICAL PSEUDONYMS Suggested additions and corrections always welcome 20th CENTURY Adler, Ruth Ray Waterman Ajax Montagu Slater [in Left Review, which he helped create & edited in 1934] Ajax Junior Guy A Aldred (in the Agnostic Journal). Allen, C Chimen Abramsky [CP National Jewish Committee] Allen, Peter Salme Dutt [née Murrik aka Pekkala; married to Rajani Palme Dutt] Anderson, Irene Constance Haverson [George Lansbury's granddaughter, Comintern courier] Andrews, R F Andrew Rothstein [CPGB] Arkwright, John Randall Swingler [CP writer] Ashton, Teddy Charles Allen Clarke. 1863-1935. [Lancashire dialect novelist and socialist] Atticus William MacCall [pioneer anarchist, reviewer for The National Reformer] Aurelius, Marcus Walter Padley [author of Am I My Brother’s Keeper? Gollancz 1945; Labour MP and President of USDAW] Avis Alfred Sherman (before he became a close advisor to Margaret Thatcher, he had been in the CP in the 1940s, and used this name to write on Jewish issues) Barclay, P J John Archer (Trotskyist civil servant) Baron, Alexander Alec Bernstein [novelist] Barrett, George George Ballard [anarchist] Barrister, A Mavis Hill [Justice in England, LBC, 1938] Thurso, Berwick Morris Blythman [Scottish radical poet, singer-songwriter] B V James Thomson [Radical poet and reviewer] Bell, Lily Mrs Bream Pearce [in Keir Hardie’s Labour Leader] Bennet or Bennett Goldfarb [ECCI rep. to GB & Ireland; Head of Anglo-American Secretariat, C.I.; married Rose Cohen, CPGB. Both shot in 1937] Aka Lipec, Petrovsky, Breguer, Humboldt Berwick, -

The T)Iary of Samuel Breck, 18 14-1822

The T)iary of Samuel Breck, 18 14-1822 URING the first half of the nineteenth century Samuel Breck was one of Philadelphia's outstanding citizens. Although D not in business, and seldom occupying political office, his personality and character were such as to gain him the highest respect. At the numerous public meetings of the day, he was cus- tomarily called to the chair. A man of benign personality who is said never to have had a serious quarrel, he was a scholarly person, a man of reading and letters, and yet also one whose business judgment and financial acumen were well recognized. Born in Boston in 1771, Breck was the eldest son of Samuel Breck, Sr., a socially prominent merchant who in 1779 was ap- pointed fiscal agent to the French forces in America. This led to an intimacy with their leaders and resulted in his sending his son to France to attend the aristocratic, military school at Soreze, where Samuel studied for more than four years before returning to Boston in 1787. This experience, unusual, perhaps unique, for an American, was strengthened by a second visit to the Continent and a lengthy stay in England in 1790-1791. In 1792 Samuel Breck accompanied his parents to Philadelphia, where they were to remain and to enjoy years of well-merited dis- tinction as social leaders in the nation's capital. A measure of the elder Breck's prestige may be seen in the offer he received of the presidency of the Bank of the United States. He declined the honor just, as years later, his son-in-law James Lloyd declined the presi- dency of the Second Bank of the United States.