Christopher Isherwood's Camp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATEX for Beginners

LATEX for Beginners Workbook Edition 5, March 2014 Document Reference: 3722-2014 Preface This is an absolute beginners guide to writing documents in LATEX using TeXworks. It assumes no prior knowledge of LATEX, or any other computing language. This workbook is designed to be used at the `LATEX for Beginners' student iSkills seminar, and also for self-paced study. Its aim is to introduce an absolute beginner to LATEX and teach the basic commands, so that they can create a simple document and find out whether LATEX will be useful to them. If you require this document in an alternative format, such as large print, please email [email protected]. Copyright c IS 2014 Permission is granted to any individual or institution to use, copy or redis- tribute this document whole or in part, so long as it is not sold for profit and provided that the above copyright notice and this permission notice appear in all copies. Where any part of this document is included in another document, due ac- knowledgement is required. i ii Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is LATEX?..........................1 1.2 Before You Start . .2 2 Document Structure 3 2.1 Essentials . .3 2.2 Troubleshooting . .5 2.3 Creating a Title . .5 2.4 Sections . .6 2.5 Labelling . .7 2.6 Table of Contents . .8 3 Typesetting Text 11 3.1 Font Effects . 11 3.2 Coloured Text . 11 3.3 Font Sizes . 12 3.4 Lists . 13 3.5 Comments & Spacing . 14 3.6 Special Characters . 15 4 Tables 17 4.1 Practical . -

Christopher Isherwood Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pk0gr7 No online items Christopher Isherwood Papers Finding aid prepared by Sara S. Hodson with April Cunningham, Alison Dinicola, Gayle M. Richardson, Natalie Russell, Rebecca Tuttle, and Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2, 2000. Updated: January 12, 2007, April 14, 2010 and March 10, 2017 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Christopher Isherwood Papers CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Christopher Isherwood Papers Dates (inclusive): 1864-2004 Bulk dates: 1925-1986 Collection Number: CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 Creator: Isherwood, Christopher, 1904-1986. Extent: 6,261 pieces, plus ephemera. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of British-American writer Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), chiefly dating from the 1920s to the 1980s. Consisting of scripts, literary manuscripts, correspondence, diaries, photographs, ephemera, audiovisual material, and Isherwood’s library, the archive is an exceptionally rich resource for research on Isherwood, as well as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and others. Subjects documented in the collection include homosexuality and gay rights, pacifism, and Vedanta. Language: English. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department, with two exceptions: • The series of Isherwood’s daily diaries, which are closed until January 1, 2030. -

CABARET and ANTIFASCIST AESTHETICS Steven Belletto

CABARET AND ANTIFASCIST AESTHETICS Steven Belletto When Bob Fosse’s Cabaret debuted in 1972, critics and casual viewers alike noted that it was far from a conventional fi lm musical. “After ‘Cabaret,’ ” wrote Pauline Kael in the New Yorker , “it should be a while before per- formers once again climb hills singing or a chorus breaks into song on a hayride.” 1 One of the fi lm’s most striking features is indeed that all the music is diegetic—no one sings while taking a stroll in the rain, no one soliloquizes in rhyme. The musical numbers take place on stage in the Kit Kat Klub, which is itself located in a specifi c time and place (Berlin, 1931).2 Ambient music comes from phonographs or radios; and, in one important instance, a Hitler Youth stirs a beer-garden crowd with a propagandistic song. This directorial choice thus draws attention to the musical numbers as musical numbers in a way absent from conventional fi lm musicals, which depend on the audience’s willingness to overlook, say, why a gang mem- ber would sing his way through a street fi ght. 3 In Cabaret , by contrast, the songs announce themselves as aesthetic entities removed from—yet expli- cable by—daily life. As such, they demand attention as aesthetic objects. These musical numbers are not only commentaries on the lives of the var- ious characters, but also have a signifi cant relationship to the fi lm’s other abiding interest: the rise of fascism in the waning years of the Weimar Republic. -

LIST of MOVIES from PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from Recent to Old) *See Editing Instructions at Bottom of Document

LIST OF MOVIES FROM PAST SFFR MOVIE NIGHTS (Ordered from recent to old) *See editing Instructions at bottom of document 2020: Jan – Judy Feb – Papi Chulo Mar - Girl Apr - GAME OVER, MAN May - Circus of Books 2019: Jan – Mario Feb – Boy Erased Mar – Cakemaker Apr - The Sum of Us May – The Pass June – Fun in Boys Shorts July – The Way He Looks Aug – Teen Spirit Sept – Walk on the Wild Side Oct – Rocketman Nov – Toy Story 4 2018: Jan – Stronger Feb – God’s Own Country Mar -Beach Rats Apr -The Shape of Water May -Cuatras Lunas( 4 Moons) June -The Infamous T and Gay USA July – Padmaavat Aug – (no movie night) Sep – The Unknown Cyclist Oct - Love, Simon Nov – Man in an Orange Shirt Dec – Mama Mia 2 2017: Dec – Eat with Me Nov – Wonder Woman (2017 version) Oct – Invaders from Mars Sep – Handsome Devil Aug – Girls Trip (at Westfield San Francisco Centre) Jul – Beauty and the Beast (2017 live-action remake) Jun – San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival selections May – Lion Apr – La La Land Mar – The Heat Feb – Sausage Party Jan – Friday the 13th 2016: Dec - Grandma Nov – Alamo Draft House Movie Oct - Saved Sep – Looking the Movie Aug – Fourth Man Out, Saving Face July – Hail, Caesar June – International Film festival selections May – Selected shorts from LGBT Film Festival Apr - Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (Run, Milkha, Run) Mar – Trainwreck Feb – Inside Out Jan – Best In Show 2015: Dec - Do I Sound Gay? Nov - The best of the Golden Girls / Boys Oct - Love Songs Sep - A Single Man Aug – Bad Education Jul – Five Dances Jun - Broad City series May – Reaching for the Moon Apr - Boyhood Mar - And Then Came Lola Feb – Looking (Season 2, Episodes 1-4) Jan – The Grand Budapest Hotel 2014: Dec – Bad Santa Nov – Mrs. -

Books for the College Bound Fiction

BOOKS FOR THE COLLEGE BOUND FICTION Anderson, Sherwood. Winesburg, Ohio, 1919. A collection of short stories lays bare the life of a small town in the Midwest. 247 p. A5492WI Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice, 1813. “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” This witty comedy of manners explores the intricacies of courtship in 18th-century England. 281 p. A933PR Bellamy, Edward. Looking Backward: 2000-1887, 1887. Written in 1887 about a young man who travels in time to a utopian year 2000, where economic security and a healthy moral environment have reduced crime. 470 p. B4357L Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451, 1951. Enter a futuristic world where reading is prohibited because it stimulates thought, and firemen “protect” society by burning books. 179 p. B7982F Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre, 1847. Jane Eyre, a penniless orphan, is engaged as governess for the mysterious Mr. Rochester. 248 p. B8695J Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights, 1847. One of the first gothic novels. Passion, hate, and revenge abound in the turbulent story of Heathcliff and Catherine’s obsessive love. 390 p. B8697W Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865. Alice falls down a rabbit-hole and enters the whimsical, nonsensical world of the Queen of Hearts, Cheshire cat, and Mad Hatter. 143 p. C3196AL Cather, Willa. My Ántonia, 1918. Soulful portrait of Ántonia Shimerda, a Czech immigrant who faces heartbreak, disillusionment, and social ostracism in frontier Nebraska. 238 p. C363MY Chopin, Kate. The Awakening, 1899. The story of a New Orleans woman who abandons her husband and children to search for love and self-understanding. -

Discipleship in the Works of Christopher Isherwood

Prague Journal of English Studies Volume 8, No. 1, 2019 ISSN: 1804-8722 (print) '2,10.2478/pjes-2019-0005 ISSN: 2336-2685 (online) A Bond Stronger Than Marriage: Discipleship in the Works of Christopher Isherwood Kinga Latała Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland is paper is concerned with Christopher Isherwood’s portrayal of his guru-disciple relationship with Swami Prabhavananda, situating it in the tradition of discipleship, which dates back to antiquity. It discusses Isherwood’s (auto)biographical works as records of his spiritual journey, infl uenced by his guru. e main focus of the study is My Guru and His Disciple, a memoir of the author and his spiritual master, which is one of Isherwood’s lesser-known books. e paper attempts to examine the way in which a commemorative portrait of the guru, suggested by the title, is incorporated into an account of Isherwood’s own spiritual development. It discusses the sources of Isherwood’s initial prejudice against religion, as well as his journey towards embracing it. It also analyses the facets of Isherwood and Prabhavananda’s guru-disciple relationship, which went beyond a purely religious arrangement. Moreover, the paper examines the relationship between homosexuality and religion and intellectualism and religion, the role of E. M. Forster as Isherwood’s secular guru, the question of colonial prejudice, as well as the reception of Isherwood’s conversion to Vedanta and his religious works. Keywords Christopher Isherwood; Swami Prabhavananda; My Guru and His Disciple; discipleship; guru; memoir e present paper sets out to explore Christopher Isherwood’s depiction of discipleship in My Guru and His Disciple (1980), as well as relevant diary entries and letters. -

Goodbye to Berlin: Erich Kästner and Christopher Isherwood

Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association ISSN: 0001-2793 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yjli19 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE To cite this article: YVONNE HOLBECHE (2000) GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KÄSTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD, Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association, 94:1, 35-54, DOI: 10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1179/aulla.2000.94.1.004 Published online: 31 Mar 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 33 Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yjli20 GOODBYE TO BERLIN: ERICH KASTNER AND CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD YVONNE HOLBECHE University of Sydney In their novels Fabian (1931) and Goodbye to Berlin (1939), two writers from different European cultures, Erich Mstner and Christopher Isherwood, present fictional models of the Berlin of the final years of the Weimar Republic and, in Isherwood's case, the beginning of the Nazi era as wel1. 1 The insider Kastner—the Dresden-born, left-liberal intellectual who, before the publication ofFabian, had made his name as the author not only of a highly successful children's novel but also of acute satiric verse—had a keen insight into the symptoms of the collapse of the republic. The Englishman Isherwood, on the other hand, who had come to Berlin in 1929 principally because of the sexual freedom it offered him as a homosexual, remained an outsider in Germany,2 despite living in Berlin for over three years and enjoying a wide range of contacts with various social groups.' At first sight the authorial positions could hardly be more different. -

44-Christopher Isherwood's a Single

548 / RumeliDE Journal of Language and Literature Studies 2020.S8 (November) Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life / G. Güçlü (pp. 548-562) 44-Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life Gökben GÜÇLÜ1 APA: Güçlü, G. (2020). Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man: A work of art produced in the afternoon of an author’s life. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (Ö8), 548-562. DOI: 10.29000/rumelide.816962. Abstract Beginning his early literary career as an author who nurtured his fiction with personal facts and experiences, many of Christopher Isherwood’s novels focus on constructing an identity and discovering himself not only as an adult but also as an author. He is one of those unique authors whose gradual transformation from late adolescence to young and middle adulthood can be clearly observed since he portrays different stages of his life in fiction. His critically acclaimed novel A Single Man, which reflects “the afternoon of his life;” is a poetic portrayal of Isherwood’s confrontation with ageing and death anxiety. Written during the early 1960s, stormy relationship with his partner Don Bachardy, the fight against cancer of two of his close friends’ (Charles Laughton and Aldous Huxley) and his own health problems surely contributed the formation of A Single Man. The purpose of this study is to unveil how Isherwood’s midlife crisis nurtured his creativity in producing this work of fiction. From a theoretical point of view, this paper, draws from literary gerontology and ‘the Lifecourse Perspective’ which is a theoretical framework in social gerontology. -

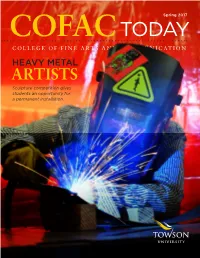

COFAC Today Spring 2017

Spring 2017 COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION HEAVY METAL ARTISTS Sculpture competition gives students an opportunity for a permanent installation. COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION DEAN, COLLEGE OF DEAR FRIENDS, FAMILIES, AND COLLEAGUES, FINE ARTS & COMMUNICATION Susan Picinich The close of an academic year brings with it a sense of pride and anticipation. The College of Fine Arts and Communication bustles with excitement as students finish final projects, presentations, exhibitions, EDITOR Sedonia Martin concerts, recitals and performances. Sr. Communications Manager In this issue of COFAC Today we look at the advancing professional career of dance alum Will B. Bell University Marketing and Communications ’11 who is making his way in the world of dance including playing “Duane” in the live broadcast of ASSOCIATE EDITOR Hairspray Live, NBC television’s extravaganza. Marissa Berk-Smith Communications and Outreach Coordinator The Asian Arts & Culture Center (AA&CC) presented Karaoke: Asia’s Global Sensation, an exhibition College of Fine Arts and Communication that explored the world-wide phenomenon of karaoke. Conceived by AA&CC director Joanna Pecore, WRITER students, faculty and staff had the opportunity to belt out a song in the AA&CC gallery while learning Wanda Haskel the history of karaoke. University Marketing and Communications DESIGNER Music major Noah Pierre ’19 and Melanie Brown ’17 share a jazz bond. Both have been playing music Rick Pallansch since childhood and chose TU’s Department of Music Jazz Studies program. Citing outstanding faculty University Marketing and Communications and musical instruction, these students are honing their passion of making music and sharing it with PHOTOGRAPHY the world. -

The Novels of Christopher Isherwood

• - '1 .' 1 THE NOVELS OF CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD " .r -----------------------~------ ---------- ( ~ .... 'o( , • 1 • , \ J .. .. .J., .. ~ 'i':;., t , • ) .. \ " NARCISSUS OBSERVED AND OBSERVING: THE NOVELS OF C~RISTOPHER 1SI'lERWOOD " By Wiltiam Aitken , / Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Master of Arts Degree . Department of'English ~J • ~1cG i 11 Uni ve~s i ty '. , 2 August 1974 .'J . f .' '. li ' . .~ ~ 4-' '\ .. • .( 1 , 1975 ABSTRACT \ • 1, • "Narcissis Obser,\ed and,Observing: The Novels of ~hristoPhe'r Isherwood" deals with narcissi~... --both limitless and limited--as a constant theme running through the novels of Christopher Isher'(fOod. Narcissism is examined in its mythical and psychoanalytlcal contexts, with special emphasis given to the writings of Freud and Marcuse. Par ticular attention is paid~to the author's homosexuality and his various works that deal with homosexuality: an attempt is made to show how » nârcissism may function as a vital and invaluable creative asset for the homosexual author. RESUME "Narc1sse observé et observant: Les Roman~de Christopher r - Isherwood. 11 Cet ouvrage démontre que le narcissisme (à la fois limité et sans limites) est, un thème constant des romans ~e Christopher Ishe~ wood. le phénomêne du narci~sisme est analysé dans ses contextes mythiques et psychanalytiques avec une insistance particuli~re sur les oeuvres de Freud et de Marcuse. L'étude porte un~ attentlon sp€ciale" "à llhomos~xualité de l'auteur et à ses oeuvres diverses et essaie de montrer comment le narcissisme peut être une source d'lnspiration ( v~ta1e et inestimable pour l'écrivain homasexuel . • • PREFACE 1 wish to thank Professor Donald Rùbin for his h~lp a~d suggestions concerning Isherwood's works and pertinent backgr~nd t mate~ia11 a1so, Professor Bruce Garside for his guidance concerning narcissism and psychoanalytic theory. -

Berthold Viertel

Katharina Prager BERTHOLD VIERTEL Eine Biografie der Wiener Moderne 2018 BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Veröffentlicht mit der Unterstützug des Austrian Science Fund (FWF) : PUB 459-G28 Open Access: Wo nicht anders festgehalten, ist diese Publikation lizenziert unter der Creative-Com- mons-Lizenz Namensnennung 4.0; siehe http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Umschlagabbildung : Berthold Viertel auf der Probe, Wien um 1953; © Thomas Kuhnke © 2018 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Wien Köln Weimar Wiesingerstraße 1, A-1010 Wien, www.boehlau-verlag.com Korrektorat : Alexander Riha, Wien Satz : Michael Rauscher, Wien Umschlaggestaltung : Michael Haderer, Wien ISBN 978-3-205-20832-7 Inhalt Ein chronologischer Überblick ....................... 7 Einleitend .................................. 19 1. BERTHOLD VIERTELS RÜCKKEHR IN DIE ÖSTERREICHISCHE MODERNE DURCH EXIL UND REMIGRATION Außerhalb Österreichs – Die Entstehung des autobiografischen Projekts 47 Innerhalb Österreichs – Konfrontationen mit »österreichischen Illusionen« ................................. 75 2. ERINNERUNGSORTE DER WIENER MODERNE Moderne in Wien ............................. 99 Monarchisches Gefühl ........................... 118 Galizien ................................... 129 Jüdisches Wien .............................. -

Picador December 2019

PICADOR DECEMBER 2019 PAPERBACK The Inflamed Mind A Radical New Approach to Depression Edward Bullmore Worldwide, depression will be the single biggest cause of disability in the next twenty years. But treatment for it has not changed much in the last three decades...until now. In this game-changing book, University of Cambridge Professor of Psychiatry Edward Bullmore reveals the breakthrough new science on the link between depression and inflammation of the body and brain. He explains how and why we now know that mental disorders can have their root cause in the immune PSYCHOLOGY / system, and outlines a future revolution in which treatments could be PSYCHOPATHOLOGY / specifically targeted to break the vicious cycle of stress, inflammation, and DEPRESSION depression. Picador | 12/31/2019 9781250318169 | $18.00 / $24.50 Can. Trade Paperback | 256 pages | Carton Qty: 32 The Inflamed Mind goes far beyond the clinic and the lab, representing a whole 8.3 in H | 5.4 in W new way of looking at how mind, brain, and body all work together in a Includes 15 black-and-white illustrations throughout sometimes-misguided effort to help us survive in a hostile world. It offers insights into the story of Western medicine, how we have got it wrong as well as Subrights: UK: Short Books; tr.: The Gener right in the past, and how we could start getting to grips with depression and Company; 1st Ser: Picador, Aud.: Picador other mental disorders much more effectively in the future. Other Available Formats: Hardcover ISBN: 9781250318145 • For readers of Atul