The Graham Greene Film Reader, Ed. David Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM HEINEMANN: AUSTRALIA First published in 1987 by HEINEMANN PUBLISHERS AUSTRALIA (A division of Octopus Publishing Group/Australia Pty Ltd) 85 Abinger Street, Richmond, Victoria, 3121. Copyright (c) 1987 by Peter Wright ISBN 0-85561-166-9 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. TO MY WIFE LOIS Prologue For years I had wondered what the last day would be like. In January 1976 after two decades in the top echelons of the British Security Service, MI5, it was time to rejoin the real world. I emerged for the final time from Euston Road tube station. The winter sun shone brightly as I made my way down Gower Street toward Trafalgar Square. Fifty yards on I turned into the unmarked entrance to an anonymous office block. Tucked between an art college and a hospital stood the unlikely headquarters of British Counterespionage. I showed my pass to the policeman standing discreetly in the reception alcove and took one of the specially programmed lifts which carry senior officers to the sixth-floor inner sanctum. I walked silently down the corridor to my room next to the Director-General's suite. The offices were quiet. Far below I could hear the rumble of tube trains carrying commuters to the West End. I unlocked my door. In front of me stood the essential tools of the intelligence officer’s trade - a desk, two telephones, one scrambled for outside calls, and to one side a large green metal safe with an oversized combination lock on the front. -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Claud Cockburn's the Week and the Anti-Nazi Intrigue That Produced

55 Fighting Fire with Propaganda: Claud Cockburn’s The Week and the Anti-Nazi Intrigue that Produced the ‘Cliveden Set,’ 1932-1939 by An Cushner “The public nervous system may be soothed by false explanations. But unless people are encouraged to look rather more coolly and deeply into these same phenomena of espionage and terrorism, they will make no progress towards any genuine self-defense against either.” --Claud Cockburn1 “Neville Chamberlain is lunching with me on Thursday, and I hope Edward Halifax.. .Apparently the Communist rag has been full of the Halifax-Lothian-Astor plot at Cliveden. people really seem to believe it.” --Nancy Astor to Lord Lothian2 In 1932, London Times editor Geoffrey Dawson sat at the desk of his former New York and Berlin correspondent, Claud Cockbum. A grandson of Scottish Lord Heniy Cockbum, the twenty-eight year old journalist had been born in China while his father was a diplomat with the British Legation during the Boxer Rebellion. Dawson attempted to dissuade Cockbum from quitting the Times, and he was sorry to see such a promising young newsman shun his aristocratic roots in order to join with the intellectual Left. After repeatedly trying to convince his fellow Oxford alumnus to reconsider his decision to resign, Dawson finally admitted defeat and sarcastically remarked to Cockbum that “[i]t does seem rather bad luck that you of all people should go Red on us.”3 Dawson had no way of knowing how hauntingly prophetic those words would prove to be. five years later, the strongly anti-communist newspaper editor’s words would come back to haunt him with a vengeance that neither man could have likely predicted. -

Channel Four and the Rediscovery of Old Movies on Television

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive Channel Four and the rediscovery of old movies on television HALL, Sheldon Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/6812/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version HALL, Sheldon (2012) Channel Four and the rediscovery of old movies on television. In: Channel Four and UK Film Culture, 1-2 November 2012, BFI Southbank. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Channel 4 and the Rediscovery of Old Movies on Television (Channel 4 and British Film Culture conference, BFI Southbank, 2 November 1982) Unlike some other contributors to this conference I will not be discussing Film on Four – but I will be discussing films on 4. In this paper I will not be concerned with Channel 4 as a producer or distributor of theatrical movies, but as an exhibitor of theatrical movies on television, and most especially as a curator of them. -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Race, Migration, and Chinese and Irish Domestic Servants in the United States, 1850-1920

An Intimate World: Race, Migration, and Chinese and Irish Domestic Servants in the United States, 1850-1920 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Andrew Theodore Urban IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advised by Donna Gabaccia and Erika Lee June 2009 © Andrew Urban, 2009 Acknowledgements While I rarely discussed the specifics of my dissertation with my fellow graduate students and friends at the University of Minnesota – I talked about basically everything else with them. No question or topic was too large or small for conversations that often carried on into the wee hours of the morning. Caley Horan, Eric Richtmyer, Tim Smit, and Aaron Windel will undoubtedly be lifelong friends, mahjong and euchre partners, fantasy football opponents, kindred spirits at the CC Club and Mortimer’s, and so on. I am especially grateful for the hospitality that Eric and Tim (and Tank the cat) offered during the fall of 2008, as I moved back and forth between Syracuse and Minneapolis. Aaron and I had the fortune of living in New York City at the same time in our graduate careers, and I have fond memories of our walks around Stuyvesant Park in the East Village and Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and our time spent with the folks of Tuesday night. Although we did not solve all of the world’s problems, we certainly tried. Living in Brooklyn, I also had the opportunity to participate in the short-lived yet productive “Brooklyn Scholars of Domestic Service” (AKA the BSDS crew) reading group with Vanessa May and Lara Vapnek. -

November 2019

MOVIES A TO Z NOVEMBER 2019 D 8 1/2 (1963) 11/13 P u Bluebeard’s Ten Honeymoons (1960) 11/21 o A Day in the Death of Donny B. (1969) 11/8 a ADVENTURE z 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932) 11/5 S Ho Booked for Safekeeping (1960) 11/1 u Dead Ringer (1964) 11/26 S 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) 11/27 P D Bordertown (1935) 11/12 S D Death Watch (1945) 11/16 c COMEDY c Boys’ Night Out (1962) 11/17 D Deception (1946) 11/19 S –––––––––––––––––––––– A ––––––––––––––––––––––– z Breathless (1960) 11/13 P D Dinky (1935) 11/22 z CRIME c Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) 11/1 Bride of Frankenstein (1935) 11/16 w The Dirty Dozen (1967) 11/11 a Adventures of Don Juan (1948) 11/18 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 11/6 P D Dive Bomber (1941) 11/11 o DOCUMENTARY a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 11/8 R Brief Encounter (1945) 11/15 Doctor X (1932) 11/25 Hz Alibi Racket (1935) 11/30 m Broadway Gondolier (1935) 11/14 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 11/20 P D DRAMA c Alice Adams (1935) 11/24 D Bureau of Missing Persons (1933) 11/5 S y Dodge City (1939) 11/8 c Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More (1974) 11/10 w Burn! (1969) 11/30 z Dog Day Afternoon (1975) 11/16 e EPIC D All About Eve (1950) 11/26 S m Bye Bye Birdie (1963) 11/9 z The Doorway to Hell (1930) 11/7 S P R All This, and Heaven Too (1940) 11/12 c Dr. -

Koningin Victoria: Een Onverwacht Feministisch Rolmodel

Koningin Victoria: een onverwacht feministisch rolmodel De verandering van de representatie van koningin Victoria in films uit de periode 1913-2017 Scriptie MA Publieksgeschiedenis Student: Anneloes Thijs Scriptiebegeleider: Dr. A. Nobel Datum: 13-06-2019 Universiteit van Amsterdam Inhoudsopgave • Inleiding pagina 3-5 Koningin Victoria in film • Hoofdstuk 1 pagina 6-19 Een blik op het verleden door historische film • Hoofdstuk 2 pagina 20-30 Koningin Victoria: het ontstaan van een karikatuur • Hoofdstuk 3 pagina 31-44 De verbeelding van Victoria als ‘perfect middle-class wife’ • Hoofdstuk 4 pagina 45-58 • Victorias politieke transformatie tot vooruitstrevende vorstin • Hoofdstuk 5 pagina 59-68 Victoria en relaties: de eeuwige zoektocht naar liefde in film • Conclusie pagina 70-74 Het ontstaan van een nieuwe karikatuur • Abstract pagina 75 • Bibliografie pagina 76-79 2 Inleiding Koningin Victoria in film: hoe het ideaalbeeld van vrouwelijkheid het historisch narratief beïnvloedt "I am every day more convinced that we women, if we are to be good women, feminine and amiable and domestic, are not fitted to reign.’1 Koningin Victoria heeft mis- schien wel het meest conser- vatieve imago van alle vrou- wen die ooit een land hebben geregeerd. We kennen haar het best zoals ze op de af- beelding hiernaast te zien is; gekleed in zwarte japonnen, rouwend om het verlies van haar dierbare echtgenoot Al- bert en omgeven door haar negen kinderen. Zoals in bo- venstaand citaat te lezen is, had zij weinig vertrouwen in de vrouwelijke helft van de samenleving wanneer het aankwam op politieke zaken. Ze preten- deerde daarom haar koninkrijk te runnen als een groot huishouden en presenteerde zichzelf naar de buitenwereld toe als de ideale huisvrouw. -

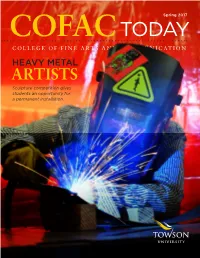

COFAC Today Spring 2017

Spring 2017 COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION HEAVY METAL ARTISTS Sculpture competition gives students an opportunity for a permanent installation. COFAC TODAY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS AND COMMUNICATION DEAN, COLLEGE OF DEAR FRIENDS, FAMILIES, AND COLLEAGUES, FINE ARTS & COMMUNICATION Susan Picinich The close of an academic year brings with it a sense of pride and anticipation. The College of Fine Arts and Communication bustles with excitement as students finish final projects, presentations, exhibitions, EDITOR Sedonia Martin concerts, recitals and performances. Sr. Communications Manager In this issue of COFAC Today we look at the advancing professional career of dance alum Will B. Bell University Marketing and Communications ’11 who is making his way in the world of dance including playing “Duane” in the live broadcast of ASSOCIATE EDITOR Hairspray Live, NBC television’s extravaganza. Marissa Berk-Smith Communications and Outreach Coordinator The Asian Arts & Culture Center (AA&CC) presented Karaoke: Asia’s Global Sensation, an exhibition College of Fine Arts and Communication that explored the world-wide phenomenon of karaoke. Conceived by AA&CC director Joanna Pecore, WRITER students, faculty and staff had the opportunity to belt out a song in the AA&CC gallery while learning Wanda Haskel the history of karaoke. University Marketing and Communications DESIGNER Music major Noah Pierre ’19 and Melanie Brown ’17 share a jazz bond. Both have been playing music Rick Pallansch since childhood and chose TU’s Department of Music Jazz Studies program. Citing outstanding faculty University Marketing and Communications and musical instruction, these students are honing their passion of making music and sharing it with PHOTOGRAPHY the world. -

Mcsorley's: John Sloan's Visual Commentary on Male Bonding, Prohibition, and the Working Class

McSorley's: John Sloan's Visual Commentary on Male Bonding, Prohibition, and the Working Class Mariea Caudill Dennison The American realist John Sloan (1871-1951) is famous for his depictions of tenement dwellers' private moments, paintings of people on the streets of New York City, and images of women. Here I will focus on the artist's render ings of men in two of his well-known paintings of McSorley's, an Irish-Ameri can bar. These paintings are best understood within the context of early twenti eth-century working class concepts of masculinity, the social history of drinking in the United States, and Sloan's own biography. The artist, a native of Pennsyl vania, was brought up in a strict Episcopalian household in which his artisan father was unable to support the family. Young Sloan worked as a Philadelphia newspaper illustrator to provide for his parents and sisters. At the paper's of fice, he saw sketch-reporters depict newsworthy events that they had observed earlier in the day, and their methods may have inspired him to establish his habit of working from memory. Although he studied briefly with Thomas Anshutz at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the young artist was largely self-taught.1 While he dutifully supported his family, Sloan achieved a freer lifestyle by joining a group of young men, many illustrators, who socialized and studied informally under Robert Henri's watchful eye.2 The raucous camaraderie, open discussion, and social freedom that Sloan found in the Philadelphia group con trasted sharply with the conservative atmosphere of his family's home.3 The young Philadelphians often gathered at Henri's studio where he encouraged 0026-3079/2006/4702-02352.50/0 American Studies, 47:2 (Summer 2006): 23-38 23 24 Mariea Caudill Dennison them to reject academic idealism and the genteel tradition. -

Face to Face AUTUMN/WINTER 2012

F2F_Issue 40_FINAL (TS)_Layout 1 20/07/2012 12:11 Page 1 Face to Face AUTUMN/WINTER 2012 The Lost Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart My Favourite Portrait by Dame Anne Owers DBE Marilyn Monroe: A British Love Affair F2F_Issue 40_FINAL (TS)_Layout 1 20/07/2012 12:11 Page 2 COVER AND BELOW Henry, Prince of Wales by Robert Peake, c.1610 This portrait will feature in the exhibition The Lost Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart from 18 October 2012 until 13 January 2013 in the Wolfson Gallery Face to Face Issue 40 Deputy Director & Director of Communications and Development Pim Baxter Communications Officer Helen Corcoran Editor Elisabeth Ingles Designer Annabel Dalziel All images National Portrait Gallery, London and © National Portrait Gallery, London, unless stated www.npg.org.uk Recorded Information Line 020 7312 2463 F2F_Issue 40_FINAL (TS)_Layout 1 20/07/2012 12:11 Page 3 FROM THE DIRECTOR THIS OCTOBER the Gallery presents The Lost cinema photographer Fred Daniels, who Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart, photographed such Hollywood luminaries as the first exhibition to explore the life and Anna May Wong, Gilda Gray and Sir Laurence legacy of Henry, Prince of Wales (1594–1612). Olivier, and Ruth Brimacombe, Assistant Curator Catharine MacLeod introduces this Curator, writes about Victorian Masquerade, fascinating exhibition, which focuses on a a small display of works from the Collection remarkable period in British history dominated which illustrate the passion for fancy dress by a prince whose death at a young age indulged by royalty, the aristocracy and artists precipitated widespread national grief, and in the nineteenth century. -

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 a Thesis Submitted to the University of Manches

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 David W. Mottram School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of contents Abstract p.4 Declaration p.5 Copyright statement p.5 Acknowledgements p.6 Introduction p.7 Terminology, sources and methods p.10 Structure of the thesis p.14 Chapter One The Lost War p.16 1.1 The place of ‘Spain’ in British politics p.17 1.2 Viewing ‘Spain’ through external perspectives p.21 1.3 The dispersal, 1939 p.26 Conclusion p.31 Chapter Two Adjustments to the Lost War p.33 2.1 The Communist Party and the International Brigaders: debt of honour p.34 2.2 Labour’s response: ‘The Spanish agitation had become history’ p.43 2.3 Decline in public and political discourse p.48 2.4 The political parties: three Spanish threads p.53 2.5 The personal price of the lost war p.59 Conclusion p.67 2 Chapter Three The lessons of ‘Spain’: Tom Wintringham, guerrilla fighting, and the British war effort p.69 3.1 Wintringham’s opportunity, 1937-1940 p.71 3.2 ‘The British Left’s best-known military expert’ p.75 3.3 Platform for influence p.79 3.4 Defending Britain, 1940-41 p.82 3.5 India, 1942 p.94 3.6 European liberation, 1941-1944 p.98 Conclusion p.104 Chapter Four The political and humanitarian response of Clement Attlee p.105 4.1 Attlee and policy on Spain p.107 4.2 Attlee and the Spanish Republican diaspora p.113 4.3 The signal was Greece p.119 Conclusion p.125 Conclusion p.127 Bibliography p.133 49,910 words 3 Abstract Complexities and divisions over British left-wing responses to the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939 have been well-documented and much studied.