How the Oscars Are So White

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Papers 2017 ~ 2018

the American Papers 2017 ~ 2018 1 The American Papers 2 The American Papers Editor-in-Chief Clayton Finn Jasmine Mayfield Managing Editors Michael Paramo Jonathan Schreiber Jena Delgado-Sette Editorial Board Roxana Arevalo Barbara Tkach Michael Gandara Jesus Pelayo Layout Editor Bahar Tahamtani Faculty Advisor Dustin Abnet Copyright © 2018 The American Studies Student Association California State University, Fullerton. All rights reserved. ISSN 10598464 3 The American Papers 4 Professor Abnet would like to thank the editors for their hard work, camaraderie, and professionalism while preparing this edi- tion of The American Papers. Their willingness to give freely of their time—even over summer break—to add to this institution is very much appreciated. He also would like to commend the authors for their exceptional papers and good-natured responses to the editorial process. Michael Paramo, Jonathan Schreiber, and Jena Delgado-Sette deserve special recognition for their service as Managing Edi- tors as does editor Michael Gandara for his assistance securing funding from the InterClub Council. Together their efforts made the production of the 2017-2018 issue possible. Professor Abnet offers special thanks to Bahar Tahamtani for her beautiful work on the layout and design of this issue. Finally, he especially would like to thank Clayton Finn and Jasmine Mayfield for serving as this volume’s Editors in Chief. Their professionalism, hard work, kindness, and dedication to the success of The American Papers has been remarkable. 5 The American Papers Welcome to the 2017-2018 American Papers! First and foremost, the American Papers is a testament to the many faculty men- tors that have spent countless hours of their time to assist students at California State University, Fullerton (CSUF) in their personal academic development and in making this journal what it is today. -

Improvisation and Birdman; Or, the Unexpected Virtue of Irony1

Improvisation and Birdman; or, the Unexpected Virtue of Irony1 Mark Kaethler Leading up to the 87th Academy Awards, reporters launched a critique on the Oscars for only nominating white actors. Headlines included The Huffington Post’s “Why It Should Bother Everyone That The Oscars Are So White,” The Guardian’s “Oscars whitewash: why have 2015’s red carpets been so overwhelmingly white?”, TIME magazine’s “Almost All The Oscar Nominees Are White,” and US Magazine’s “Oscars 2015 Nominations: Only White Actors Received Academy Award Nods and the Internet Is Outraged,” to name a few. The International Business Times went so far as to provide an infographic in their piece, “Oscars 2015 Infographic: How White Are the 87th Academy Awards?” Even Oscar host of that year, Neil Patrick Harris, remarked upon this racism early on in the show by making the following joke: “Today we honor Hollywood’s best and whitest. Sorry, brightest” (qtd. in THR staff). It is ironic in itself that Alejandro González Iñárritu’s satire of Hollywood, superhero culture, and the unbearable whiteness that proliferates them went on to win best director, best cinematography, best screenplay, and best picture, but there is a further irony embedded in a film that mocks its white cast’s desperate efforts to receive recognition, often labelling them “children” for this selfish desire. As Samantha, daughter to Riggan (Birdman’s antihero), puts it to her father in her wonderful monologue lambasting the egotism of celebrity culture: Riggan is adapting Raymond Carver’s work for the stage “for 1000 old, rich, white people” in a desperate effort to regain publicity after his fifteen minutes of fame in the early ’90s when he played the superhero Birdman. -

88Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Natalie Kojen [email protected] January 14, 2016 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 88TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, Guillermo del Toro, John Krasinski and Ang Lee announced the 88th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 14). Del Toro and Lee announced the nominees in 11 categories at 5:30 a.m. PT, followed by Boone Isaacs and Krasinski for the remaining 13 categories at 5:38 a.m. PT, at the live news conference attended by more than 400 international media representatives. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars® website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Official screenings of all motion pictures with one or more nominations will begin for members on Saturday, January 23, at the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theater. Screenings also will be held at the Academy’s Linwood Dunn Theater in Hollywood and in London, New York and the San Francisco Bay Area. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 88th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 28, 2016, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live by the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m. -

President Meets President UR Field Patrol Unit Seligman Attends State of the Union Address Hockey Star Follows Tapped for Kidnapping Team USA

CampusTHURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2016 / VOLUME 143, ISSUE 1 Times SERVING THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER COMMUNITY SINCE 1873 / campustimes.org New President Meets President UR Field Patrol Unit Seligman Attends State of the Union Address Hockey Star Follows Tapped for Kidnapping Team USA BY ANGELA LAI BY AUDREY GOLDFARB PUBLISHER CONTRIBUTING WRITER BY JUSTIN TROMBLY Confident and congenial, Tara MANAGING EDITOR Lamberti stands proud at 5’4”, the shortest goalie and only Divi- A new Department of Pub- sion III player in the country to lic Safety (DPS) patrol unit be invited to the U.S. National is set to roll out next month, Field Hockey Trials this month. coming in the wake of the The First Team All-American has kidnapping of two Univer- compiled a myriad of accolades sity seniors in early December. during her collegiate career. The The new unit, which will focus senior led the league in shutouts on giving DPS a visible and ac- this season and earned recog- cessible presence on campus, will nition as the Liberty League start patroling on Sunday, Feb. 7, Defensive Player of the Year, almost a month to the day after the but this invitation to take her students were abducted and held at talents to the next level is her gunpoint in an off-campus house. claim to fame. UR President Joel Seligman Passing up opportunities to announced the unit in a recent play at the Division I level, email to students, which dis- Lamberti chose UR to better cussed both the kidnapping and PHOTO COURTESY OF THE OFFICE OF CONGRESSWOMAN LOUISE SLAUGHTER balance academics, athletics, a Monroe County Grand Jury UR President Joel Seligman, Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi, and Representative Louise Slaughter mingle in Pelosi’s Capitol and social life, in addition to indictment against six defen- Hill office before President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address Jan. -

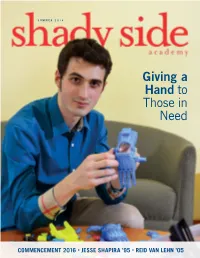

Giving a Hand to Those in Need

SUMMER 2016 Giving a Hand to Those in Need COMMENCEMENT 2016 • JESSE SHAPIRA ’95 • REID VAN LEHN ’05 Editor Lindsay Kovach Associate Editor Jennifer Roupe Contributors Val Brkich Christa Burneff Cristina Rouvalis Photography Commencement and feature photography by James Knox Additional photos provided by SSA faculty, staff, coaches, alumni, students and parents. Class notes photos are submitted by alumni and class correspondents. Design Kara Reid The following icons denote stories related to key goals Printing of SSA’s strategic vision, entitled Challenging Students to Broudy Printing Think Expansively, Act Ethically and Lead Responsibly. Shady Side Academy Magazine is published twice a year for Shady Side Academy alumni, parents and For more information, visit shadysideacademy.org/strategicvision. friends. Letters to the editor should be sent to Lindsay Kovach, Shady Side Academy, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Academic Community Pittsburgh, PA 15238. Address corrections should be Program Connections sent to the Alumni & Development Office, Shady Side Academy, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Pittsburgh, PA 15238. Junior School, 400 S. Braddock Ave., Physical Faculty Pittsburgh, PA 15221, 412-473-4400 Resources Middle School, 500 Squaw Run Road East, Pittsburgh, PA 15238, 412-968-3100 Financial Senior School, 423 Fox Chapel Rd., Students Sustainability Pittsburgh, PA 15238, 412-968-3000 www.shadysideacademy.org facebook.com/shadysideacademy twitter.com/shady_side youtube.com/shadysideacademy FSC to be placed by printer contentsSUMMER 2016 FEATURES ALSO IN THIS -

Academy Awards

Analysis of the digital conversation for the 2018 ACADEMY AWARDS March, 2018 CONTEXT ACADEMY AWARDS, 2018 On March 4th, 2018, we had the 90th Oscar Ceremony, a prize given by the AMPAS to the crème of the crop in movies, recognizing their excellence in the industries’ professionals, and is considered the greatest honor in movies worldwide. 4 THE AWARDS: THE PRIDE OF MEXICO Lately, it has become common to see Mexicans participating of the Oscars. During Oscar’s 86, 87 & 88, a Mexican took 2 statues, both as best director & best movie. This is why this year it is not surprising to see Mexico’s participation, however, we had never seen such a Mexican delivery as this one. Last year, the current president of the US, Donald Trump. While being sworn in said he would put up a wall between the US and Mexico so as to avoid immigration by illegal aliens from Lat Am; stemming from this fact and others, such as the renegotiation of NAFTA the relationship between countries has suffered. This situation has generated a friction between countries, yet, “The Academy” has shown to be against these remarks and has done so in every ceremony appealing to equality and inclusion for all cultures, preferences and genders. 5 DONALD TRUMP VS. MÉXICO After the 87th Academy awards, when Mexican national “Alejandro González Iñarritu” was awarded with 3 Oscars for his film “Birdman”, current US president “Donald Trump” tweeted a series of messages of disapproval: 6 THE MOST MEXICAN ACADEMY AWARDS On the 90th Academy Awards Mexico was more present than ever: “Coco” a Disney Pixar film centered on the Mexican The shape of water, written and directed by tradition of the day of the dead was nominated filmmaker Guillermo del Toro was nominated and awarded as best animated movie & best to 14 awards of which it got 4. -

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

The Academy Selects 2014 and 2015 Show Dates

MEDIA CONTACT Teni Melidonian, [email protected] Alison Rou , [email protected] Nicole Marostica, [email protected] March 25, 2013 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE ACADEMY SELECTS 2014 AND 2015 SHOW DATES KEY DATES ANNOUNCED FOR THE OSCARS® BEVERLY HILLS, CA - The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the ABC Television Network today announced the dates for the 86th and 87th Oscar® presentations. The 86th and 87th Academy Awards® will air live on ABC on Oscar Sunday, March 2,2014, and February 22, 2015, respectively. Key dates for the Awards season are: Saturday, November 16, 2013: The Governors Awards Monday, December 2, 2013: Official Screen Credits due Friday, December 27, 2013: Nominations voting begins Wednesday, January 8,2014: Nominations voting ends 5 p.m. PT Thursday, January 16, 2014: Oscar nominations announced Monday, February 10, 2014: Nominees Luncheon Friday, February 14, 2014: Final voting begins Saturday, February 15, 2014: Scientific and Technical Awards Tuesday, February 25,2014: Final voting ends 5 p.m. PT Oscar Sunday, March 2, 2014: 86th Academy Awards Oscar Sunday, February 22, 2015: 87th Academy Awards The 86th and 87th Academy Awards ceremonies will be held at the Dolby Theatre ™ at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live by the ABC Television Network. ### ABOUT THE ACADEMY The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is the world's preeminent movie-related organization, with a membership of more than 6,000 of the most accomplished men and women working in cinema. In addition to the annual Academy Awards - in which the members vote to select the nominees and winners - the Academy presents a diverse year-round slate of public programs , exhibitions and events; provides financial support to a wide range of other movie-related organizations and endeavors; acts as a neutral advocate in the advancement of motion picture technology; and , through its Margaret Herrick Library and Academy Film Archive , collects, preserves, . -

87Th Academy Awards Reminder List

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 87TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT LAST NIGHT Actors: Kevin Hart. Michael Ealy. Christopher McDonald. Adam Rodriguez. Joe Lo Truglio. Terrell Owens. David Greenman. Bryan Callen. Paul Quinn. James McAndrew. Actresses: Regina Hall. Joy Bryant. Paula Patton. Catherine Shu. Hailey Boyle. Selita Ebanks. Jessica Lu. Krystal Harris. Kristin Slaysman. Tracey Graves. ABUSE OF WEAKNESS Actors: Kool Shen. Christophe Sermet. Ronald Leclercq. Actresses: Isabelle Huppert. Laurence Ursino. ADDICTED Actors: Boris Kodjoe. Tyson Beckford. William Levy. Actresses: Sharon Leal. Tasha Smith. Emayatzy Corinealdi. Kat Graham. AGE OF UPRISING: THE LEGEND OF MICHAEL KOHLHAAS Actors: Mads Mikkelsen. David Kross. Bruno Ganz. Denis Lavant. Paul Bartel. David Bennent. Swann Arlaud. Actresses: Mélusine Mayance. Delphine Chuillot. Roxane Duran. ALEXANDER AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD DAY Actors: Steve Carell. Ed Oxenbould. Dylan Minnette. Mekai Matthew Curtis. Lincoln Melcher. Reese Hartwig. Alex Desert. Rizwan Manji. Burn Gorman. Eric Edelstein. Actresses: Jennifer Garner. Kerris Dorsey. Jennifer Coolidge. Megan Mullally. Bella Thorne. Mary Mouser. Sidney Fullmer. Elise Vargas. Zoey Vargas. Toni Trucks. THE AMAZING CATFISH Actors: Alejandro Ramírez-Muñoz. Actresses: Ximena Ayala. Lisa Owen. Sonia Franco. Wendy Guillén. Andrea Baeza. THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 Actors: Andrew Garfield. Jamie Foxx. Dane DeHaan. Colm Feore. Paul Giamatti. Campbell Scott. Marton Csokas. Louis Cancelmi. Max Charles. Actresses: Emma Stone. Felicity Jones. Sally Field. Embeth Davidtz. AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY: THE EVOLUTION OF GRACE LEE BOGGS 87th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AMERICAN SNIPER Actors: Bradley Cooper. Luke Grimes. Jake McDorman. Cory Hardrict. Kevin Lacz. Navid Negahban. Keir O'Donnell. Troy Vincent. Brandon Salgado-Telis. -

Analysis of Movie Popularity and Academy Award Nomination

Undergraduate/Graduate Category: Social Sciences, Business and Law Degree Level: Undergraduate Abstract ID# 1413 Empirical Analysis of Movie Popularity and Academy Award Nomination. Daryl Chingono Abstract This research examines the relationship in consumer behavior and that of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, awarding and nomination processes. The American film industry is the most popular film industry, and is the highest grossing film industry in the world. A lack of diversity and representation is a potential loss in revenue. The research uses OLS regression model analysis of time-series data, over 20 years for the highest grossing films. The model uses variables which measure consumer sentiment, profitability, genre and accreditation of films. In doing so it is possible to also observe the effects of systemic inequality within the film industry on film earnings as well as consumer behavior vs Academy Award recognition. Results Conclusion Figure 2: Table 2. Summary statistics: [1995 - 2005] • Major and Mini-major film studio funding also has an effect on the gross box mean sd skewness kurtosis min median max office earnings of a film. Introduction Rank of film 50.5 28.87 0 1.8 1 50.5 100 • In order to deal with the diversity issue in the film industry, change must be made Adjusted Total Domestic Gross Earning 58250907 56992604 3.46 24.43 7808105 39500000 684000000 with the other variables that influence gross earnings and award nomination of a The Academy Awards, or Oscars, is an annual American awards ceremony hosted by the Academy of Year 2005 6.06 0 1.79 1995 2005 2015 film. -

Archbishop Visits Nues NEWS

NILES HERALD- SPECTATOR $1.50 Thursday, February 19,2015 nilesheraldspectator.com Archbishop visits Nues NEWS NATALIE HAYES/PIONEER PRESS These animals are ready for adoption Officials tour Wright-Way. Page 12 GO iiCHERYL MANN/TH000S DANCE Chicago creativity Thodos Dance takes inspiration from the Windy City for the Feb. 21 concert at the PAM DEFIGLIO/PIONEER PRESS North Shore Center for the Performing Chicago Archbishop Blase Cupich accepts a welcome gift during a Mass at St. John Brebeuf Parish in Nues. Page 4 Arts. Page 40 ©2015 Chicago Thbune Media Group I rights reseived VEHICLE LOAN RATES AS LOW AS 1.74% APR SOC-tLOg11S3iIN J_s NOI)0 0969 I doja Isla 0.L)4WN1 comn2unhtyctedt union ITT '8SSL0TO [P O T)TSHNdd:5) T T 5I0-3I01 99INddTLog-1I 8930 Waukegan Rd. Morton Grove, XI- 60053 ApRrrAnnual Percentege Rate Apply online todiiy. Not a member yet' Contact u; toi itiis 2 NILES HERALD-SPECTATOR nilesheraldspectator.com Bob Fleck, Publisher/General Manager John Puterbaugh, Editor 312-222-3331 [email protected] Jill McDermott, Vice President of Advertising 224-500-2419; jmcdermotttribpubcom Locai News Editor: MAILING ADDRESS Richard Ray, 312-222-3339 435 N. Michigan Ave. rrayvpioneerIocaLcom Chicago, 1160611 Local Sports Editor: PUBLICATION INFORMATION: Ryan Nilsson, 312-222-2396 Nues Herald-Spectator (LiSPS 390-680) rnilsson(à)pioneerlocal.com is published 52 issues per year by ADVERTISING Chicago Tribune Media Group, Display: 312-283-7056 435 North Michigan Avenue Chicago, Classified: 866-399-0537 Illinois, 6061 1. Single copy: $150. Email: suburbanclass@tribpubcom Periodicals postage paid at Aurora IL Legals: [email protected] and additional mailing offices. -

88Th Academy Awards Special Rules for the Short Film Awards

88TH ACADEMY AWARDS SPECIAL RULES FOR THE SHORT FILM AWARDS I. DEFINITIONS A. A short film is defined as an original motion picture that has a running time of 40 minutes or less, including all credits. B. This excludes from consideration such works as: 1. previews and advertising films 2. sequences from feature-length films, such as credit sequences 3. unaired episodes of established TV series 4. unsold TV series pilots II. CATEGORIES An award shall be given for the best achievement in each of two categories. A. Animated Short Film An animated film is created by using a frame-by-frame technique, and usually falls into one of the two general fields of animation: character or abstract. Some of the techniques of animating films include cel animation, computer animation, stop-motion, clay animation, pixilation, cutouts, pins, camera multiple pass imagery, kaleidoscopic effects, and drawing on the film frame itself. Documentary short subjects that are animated may be submitted in either the Animated Short Film category or the Documentary Short Subject category, but not both. B. Live Action Short Film A live action film uses live action techniques as the basic medium of entertainment. Documentary short subjects will not be accepted in the live action category. III. ELIGIBILITY A. To be eligible for award consideration for the 88th Awards year, a short film must fulfill one of the following qualifying criteria between October 1, 2014, and September 30, 2015. This qualification must take place within two years of the film’s completion date: 1. The picture must have been publicly exhibited for paid admission in a commercial motion picture theater in Los Angeles County for a run of at least seven consecutive days with at least one screening a day prior to public exhibition or distribution by any nontheatrical means.