The Development and Improvement of Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0.City 00.City 00000078B96b.City 000000799469.City 00002534.City 00268220901492.City 0037841796875.City 0053062438965.City 00683

0.city 00.city 00000078b96b.city 000000799469.city 00002534.city 00268220901492.city 0037841796875.city 0053062438965.city 00683e059be430973bcf2e13ef304fa996f5cb5a.city 0069580078125.city 007.city 008a.city 009115nomiyama.city 00919723510742.city 00gm02900-shunt.city 00gm02910-mhunt.city 00gs.city 00pe.city 010474731582894636.city 012.city 012179f708f91d34c3ee6388fa714fbb592b8d51.city 01280212402344.city 013501909eecc7609597e88662dd2bbcde1cce33.city 016317353468378814.city 017-4383827.city 01984024047851.city 01au.city 01gi.city 01mk.city 01tj.city 01zu.city 02.city 02197265625.city 022793953113625864.city 024169921875.city 02524757385254.city 0295524597168.city 02957129478455.city 02eo.city 02fw.city 03.city 03142738342285.city 03311157226562.city 03606224060056.city 0371.city 03808593749997.city 0390625.city 03a9f48f544d8eb742fe542ff87f697c74b4fa15.city 03ae.city 03bm.city 03fe252f0880245161813aaf4f2f4d7694b56f53.city 03fr.city 03uz.city 03wn.city 03zf.city 040.city 0401552915573.city 0402.city 0441436767578.city 04507446289062.city 04508413134766.city 04642105102536.city 05159759521484.city 05380249023437.city 0565036083984.city 0571.city 05rz.city 05sz.city 05va.city 05wa.city 06.city 0605239868164.city 06274414062503.city 06542968749997.city 0656095147133.city 06618082523343.city 0666be2f5be967dabd58cdda85256a0b2b5780f5.city 06735591116265432.city 06739044189453.city 06828904151916.city 06876373291013.city 06915283203125.city 06ez.city 06pt.city 07225036621094.city 0737714767456.city 07420544702148.city 07520144702147.city 07604598999023.city -

Father Ted 5 Entertaining Father Stone 6 the Passion of Saint Tibulus 7 Competition Time 8 and God Created Woman 9 Grant Unto Him Eternal Rest 10 SEASON 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PAGE Introduction 3 SEASON 1 Good Luck, Father Ted 5 Entertaining Father Stone 6 The Passion of Saint Tibulus 7 Competition Time 8 And God Created Woman 9 Grant Unto Him Eternal Rest 10 SEASON 2 Hell 13 Think Fast, Father Ted 14 Tentacles of Doom 15 Old Grey Whistle Theft 16 A Song for Europe 17 The Plague 18 Rock A Hella Ted 19 Alcohol and Rollerblading 20 New Jack City 21 Flight into Terror 22 SEASON 3 Are You Right There, Father Ted 25 Chirpy Burpy Cheap Sheep 26 Speed 3 27 The Mainland 28 Escape from Victory 29 Kicking Bishop Brennan Up the Arse 30 Night of the Nearly Dead 31 Going to America 32 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPECIAL EPISODES PAGE A Christmassy Ted 35 ULTIMATE EPISODE RANK 36 - 39 ABOUT THE CRITIC 40 3 INTRODUCTION Father Ted is the pinnacle of Irish TV; a much-loved sitcom that has become a cult classic on the Emerald Isle and across the globe. Following the lives of three priests and their housekeeper on the fictional landmass of Craggy Island, the series, which first aired in 1995, became an instant sensation. Although Father Ted only ran for three seasons and had wrapped by 1998, its cult status reigns to this very day. The show is critically renowned for its writing by Graham Linehan and Arthur Mathews, which details the crazy lives of the parochial house inhabitants: Father Ted Crilly (Dermot Morgan), Father Dougal McGuire (Ardal O'Hanlon), Father Jack Hackett (Frank Kelly), and Mrs Doyle (Pauline McLynn). -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

GSN Edition 06-24-20

The MIDWEEK Tuesday, June 24, 2014 Goodland1205 Main Avenue, Goodland, Star-News KS 67735 • Phone (785) 899-2338 $1 Volume 82, Number 50 12 Pages Goodland, Kansas 67735 inside Run with the Law today More lo- cal news and views from your Goodland Star-News Outlaws win tourney The Goodland American Legion Baseball team won the Levi Hayden Memorial Tournament on Saturday. See Page 11 Goodland Police Chief Cliff Couch holds the torch for the opening lap of the Run with as well as from Golden West. For more pictures, See Page 5. the Law held Saturday at the Goodland High School track. Couch was surrounded Photo by Pat Schiefen/The Goodland Star-News by fellow law enforcement officers. Runners and walkers were from the community weather Intentional burn 69° Police seek help 10 a.m. Monday Today finding vandals • Sunset, 8:18 p.m. Wednesday The Goodland Police Depart- be in the thousands of dollars. • Sunrise, 5:22 a.m. ment is asking for help locating the The department is asking that • Sunset, 8:18 p.m. perpetrators of a string of thefts and anyone with information about the Midday Conditions vandalism that has been occurring case contact the police at (785) 890- • Soil temperature 68 degrees since last Tuesday. 4570 or the Crimestoppers hotline • Humidity 68 percent Based on the department’s inves- at (785) 899-5665. Those providing • Sky mostly sunny tigation, suspects have stolen solar tips may remain anonymous. Any- • Winds north 7 mph powered yard lights from several one providing information leading • Barometer 30,30 inches homes and are using them as projec- to an arrest in this case is eligible for and falling tiles to smash nearby car windows. -

View at Your Own Risk: Gang Movies and Spectator Violence

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 12 Number 2 Article 8 3-1-1992 View at your Own Risk: Gang Movies and Spectator Violence Stephanie J. Berman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephanie J. Berman, View at your Own Risk: Gang Movies and Spectator Violence, 12 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 477 (1992). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol12/iss2/8 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIEW AT YOUR OWN RISK: GANG MOVIES AND SPECUATOR VIOLENCE I. INTRODUCTION On his way home from work in a Boston area ski shop, sixteen-year- old Marty Yakubowicz was confronted by an intoxicated teen-ager re- turning from viewing the film The Warriors.' The teen told Marty, "I want you, I'm going to get you"-a line from the movie; then the teen fatally stabbed Marty.2 Approximately one month later, on March 24, 1979, fifteen-year-old Jocelyn Vargas headed for the bus home after seeing the San Francisco premiere of BoulevardNights. 3 Caught in the crossfire between two rival gangs who were also leaving the theater, she sustained a gunshot wound in the neck.4 Both of these incidents arguably present examples of life imitating art.5 These youths had viewed gang-themed motion pictures containing violent acts that likely triggered their subsequent violent behavior. -

Vol. 47 No. 1, September 21, 1995

— NEWS — ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT — SPORTS -— The Circle and Comm Dept. Check out the new A&E section It's a changing of the guard receive the AP wire service. for entertainment news and reviews at the McCann Center -PAGE 2 -PAGE 10 -PAGE 16 Volume 47, Number 1 The Student Newspaper of Marist College September 21,1995 Students enraged over financial aid foul-up by MEREDITH KENNEDY file remained incomplete and he knew I had worked hard to cial need," Fennell said. "I re for Financial Aid (MAPP), the Managing Editor therefore they may not have get and maintain my scholar gret all the problems it caused." Free Application for Federal been able to receive their schol ship." According to Fennell, the cer Student Aid (FAFSA) and have Approximately 200 returning arship. ;•'.'. Craig Fennell, director of Fi tified letters were supposed to a copy of a parent and student Marist students were wrongly Senior Norie Mozzone has nancial Aid, said he did send the be sent to those who had not federal and state tax return. informed that their merit schol maintained and achieved Deans certified letters, but explained completed the information nec According to the guidelines arships were not being renewed List status but received a letter that a mistake was made in the essary for receiving aid for fi for the four year merit scholar during the summer vacation. sometime in early August. mailing process. nancial reas'o'ns.- ship the student's only respon The students were each sent "My father went through the "I made a mistake when I was He explained that all need sibility is to maintain a GPA of roof and blamed me," Mozzone sending out notices to those based applicants must complete a certified letter, postmarked July Please see Financial, page 4.. -

December 31, 2017 - January 6, 2018

DECEMBER 31, 2017 - JANUARY 6, 2018 staradvertiser.com WEEKEND WAGERS Humor fl ies high as the crew of Flight 1610 transports dreamers and gamblers alike on a weekly round-trip fl ight from the City of Angels to the City of Sin. Join Captain Dave (Dylan McDermott), head fl ight attendant Ronnie (Kim Matula) and fl ight attendant Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham) as they travel from L.A. to Vegas. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 2, on Fox. Join host, Lyla Berg, as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Mike Carr, President & CEO, USS Missouri Memorial Association that make Steve Levins, Executive Director, Office of Consumer Protection, DCCA 1st & 3rd Wednesday Dr. Lynn Babington, President, Chaminade University Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30pm Dr. Raymond Jardine, Chairman & CEO, Native Hawaiian Veterans Channel 53 special. Brandon Dela Cruz, President, Filipino Chamber of Commerce of Hawaii ON THE COVER | L.A. TO VEGAS High-flying hilarity Winners abound in confident, brash pilot with a soft spot for his (“Daddy’s Home,” 2015) and producer Adam passengers’ well-being. His co-pilot, Alan (Amir McKay (“Step Brothers,” 2008). The pair works ‘L.A. to Vegas’ Talai, “The Pursuit of Happyness,” 2006), does with the company’s head, the fictional Gary his best to appease Dave’s ego. Other no- Sanchez, a Paraguayan investor whose gifts By Kat Mulligan table crew members include flight attendant to the globe most notably include comedic TV Media Bernard (Nathan Lee Graham, “Zoolander,” video website “Funny or Die.” While this isn’t 2001) and head flight attendant Ronnie the first foray into television for the produc- hina’s Great Wall, Rome’s Coliseum, (Matula), both of whom juggle the needs and tion company, known also for “Drunk History” London’s Big Ben and India’s Taj Mahal demands of passengers all while trying to navi- and “Commander Chet,” the partnership with C— beautiful locations, but so far away, gate the destination of their own lives. -

19.8 Mil War Chest

$4.50 (U.S.), (CAN.), C3.50 (U.K.) $5.50 IN THIS ISSUE 35 FM, 16.50 Dfl, DK 59.50, DM20, 12,000 Lire fr%r%»,c47ÿ:;,"t:tÑ`Yir*%Yk,j-1.il.irr, I a RIAA Sets April Date 000617973 4401 9108 MI ï Z TFNLY For Introduction Of Ara A Z 374C IF Performance -Right Bill LCING RCI: CA 90801 I°i PAGE 4 Feds Probe Top Philly Concert Promoter R PAGE 5 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT FEBRUARY 23, 1991 ADVERTISEMENTS $19.8 Mil War Chest Tough Times Forcing for ILK Video Drive Tour Promoters, Agents BY PETER DEAN Changing of the guard foreseen see page 88 To Weigh LONDON- Europe's first heavy- on VSDA board ... New Options weight generic video advertising BY THOM DUFFY ists to hold down their fees. campaign kicks off Wednesday (20) Wednesday's U.K. launch is ex- "I, for one, have always been opti- as U.K. video distributors seek to pected to start with a 60- second TV TAMPA, Fla. -In the face of the re- mistic," says veteran New York pro- reverse the current trend of declin- commercial, half of which is devoted cession, U.S. promoters, booking moter Ron Delsener. "I am pessimis- EMF UNBELIEVABLE ing rentals. to a generic message. The debut of agents, and venue operators are tic" about this summer. Although title-led joint advertis- the second commercial, which in- bracing for a tough touring season In contrast, leading European con- ing has been tested in the past, the cludes location shooting, has been this spring and summer. -

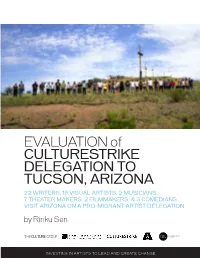

EVALUATION of CULTURESTRIKE DELEGATION to TUCSON

EVALUATION of CULTURESTRIKE DELEGATION TO TUCSON, ARIZONA 22 WRITERS, 16 VISUAL ARTISTS, 2 MUSICIANS, 7 THEATER MAKERS, 2 FILMMAKERS, & 3 COMEDIANS VISIT ARIZONA ON A PRO-MIGRANT ARTIST DELEGATION by Rinku Sen INVESTING IN ARTISTS TO LEAD AND CREATE CHANGE EVALUATION OF CULTURESTRIKE DELEGATION TO TUCSON, ARIZONA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i NARRATIVE 1 CULTURESTRIKE FELLOW BIOS 15 STAFF BIOS 21 ITINERARY 22 Acknowledgements This report was made possible in part by a grant from the Surdna Foundation and Unbound Philanthropy. The report was authored by Rinku Sen of Applied Research Center. Additional assistance was provided by Erin Potts, Jeff Chang, Ken Chen, Gan Golan, and Favianna Rodriguez. The report’s author greatly benefited from conversations with artists, writers and cultural workers of the CultureStrike. This project was coordinated by Favianna Rodriguez for The Cul- ture Group and CultureStrike. We are very grateful to the interviewees for their time and will- ingness to share their views and opinions. Cover photo: B+ About the Organizations who made this possible: Founded in 1991, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop is a home for Asian American stories The Culture Group (TCG), a collaboration of social change and the thrilling ideas that comprise Asian Ameri- experts and creative producers, joined together to advance can alternative culture. We’re a 21st century arts progressive change through expansive, strategic and values- space: a literary events curator, an anti-racist intervention, driven cultural organizing. TCG identifies, studies and deploys and an editorial platform building the future of Asian Ameri- effective models for increasing the creative industries’ and in- can intellectual conversation. -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 3-2-2017 On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy Evan Nave Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Nave, Evan, "On My Grind: Freestyle Rap Practices in Experimental Creative Writing and Composition Pedagogy" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 697. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/697 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON MY GRIND: FREESTYLE RAP PRACTICES IN EXPERIMENTAL CREATIVE WRITING AND COMPOSITION PEDAGOGY Evan Nave 312 Pages My work is always necessarily two-headed. Double-voiced. Call-and-response at once. Paranoid self-talk as dichotomous monologue to move the crowd. Part of this has to do with the deep cuts and scratches in my mind. Recorded and remixed across DNA double helixes. Structurally split. Generationally divided. A style and family history built on breaking down. Evidence of how ill I am. And then there’s the matter of skin. The material concerns of cultural cross-fertilization. Itching to plant seeds where the grass is always greener. Color collaborations and appropriations. Writing white/out with black art ink. Distinctions dangerously hidden behind backbeats or shamelessly displayed front and center for familiar-feeling consumption.